Day #2 of my sabbatical had a morning in which I’ve mostly been roped into some charity-related digital forensics… until I got distracted by dndle.app, which apparently I accidentally broke yesterday! Move Fast and Fix Things!

Tag: open source

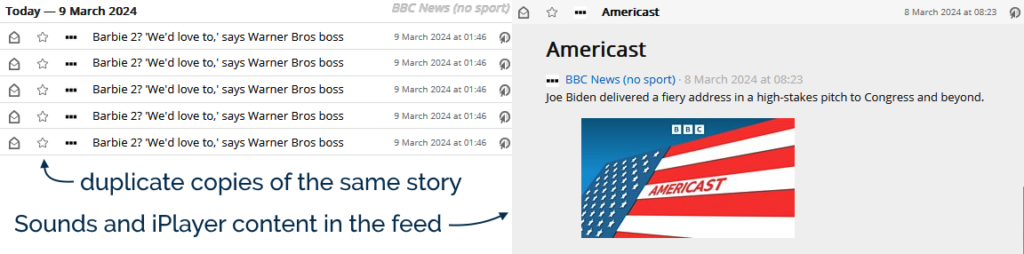

Fixing BBC News… Yet Again

The Beeb continue to keep adding more and more non-news content to the BBC News RSS feed (like this ad for the iPlayer app!), so I’ve once again had to update my script to “fix” the feed so that it only contains, y’know, news.

Transparency, Contribution, and the Future of WordPress

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

The people who make the most money in WordPress are not the people who contribute the most (Matt / Automattic really is one of the exceptions here, as I think we are). And this is a problem. It’s a moral problem. It’s just not equitable.

I agree with Matt about his opinion that a big hosting company such as WPEngine should contribute more. It is the right thing to do. It’s fair. It will make the WordPress community more egalitarian. Otherwise, it will lead to resentment. I’ve experienced that too.

…

In my opinion, we all should get a say in how we spend those contributions [from companies to WordPress]. I understand that core contributors are very important, but so are the organizers of our (flagship) events, the leadership of hosting companies, etc. We need to find a way to have a group of people who represent the community and the contributing corporations.

Just like in a democracy. Because, after all, isn’t WordPress all about democratizing?

Now I don’t mean to say that Matt should no longer be project leader. I just think that we should more transparently discuss with a “board” of some sorts, about the roadmap and the future of WordPress as many people and companies depend on it. I think this could actually help Matt, as I do understand that it’s very lonely at the top.

With such a group, we could also discuss how to better highlight companies that are contributing and how to encourage others to do so.

…

Some wise words from Joost de Valk, and it’s worth reading his full post if you’re following the WP Engine drama but would rather be focussing on looking long-term towards a better future for the entire ecosystem.

I don’t know whether Joost’s solution is optimal, but it’s certainly worth considering his ideas if we’re to come up with a new shape for WordPress. It’s good to see that people are thinking about the bigger picture here, than just wherever we find ourselves at the resolution of this disagreement between Matt/Automattic/the WordPress Foundation and WP Engine.

Thinking bigger is admirable. Thinking bigger is optimistic. Thinking bigger is future-facing.

WP Engine’s Three Problems

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

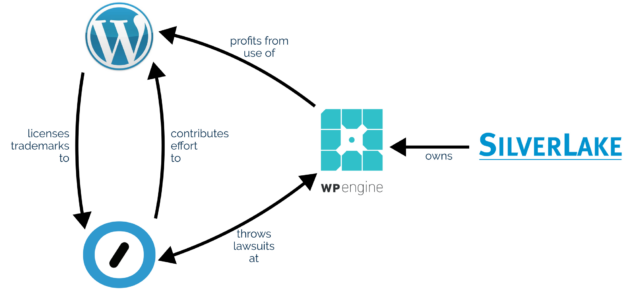

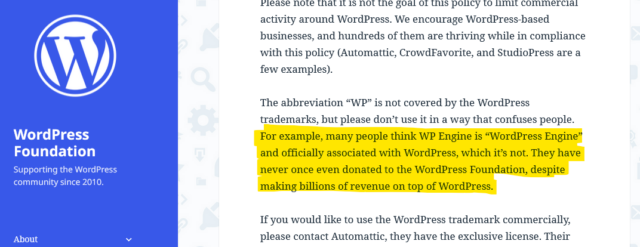

If you’re active in the WordPress space you’re probably aware that there’s a lot of drama going on right now between (a) WordPress hosting company WP Engine, (b) WordPress hosting company (among quite a few other things) Automattic1, and (c) the WordPress Foundation.

If you’re not aware then, well: do a search across the tech news media to see the latest: any summary I could give you would be out-of-date by the time you read it anyway!

A declaration of war?

Like others, I’m not sure that the way Matt publicly called-out WP Engine at WCUS was the most-productive way to progress a discussion2.

In particular, I think a lot of the conversation that he kicked off conflates three different aspects of WP Engine’s misbehaviour. That muddies the waters when it comes to having a reasoned conversation about the issue3.

I don’t think WP Engine is a particularly good company, and I personally wouldn’t use them for WordPress hosting. That’s not a new opinion for me: I wouldn’t have used them last year or the year before, or the year before that either. And I broadly agree with what I think Matt tried to say, although not necessarily with the way he said it or the platform he chose to say it upon.

Misdeeds

As I see it, WP Engine’s potential misdeeds fall into three distinct categories: moral, ethical4, and legal.

Morally: don’t take without giving back

Matt observes that since WP Engine’s acquisition by huge tech-company-investor Silver Lake, WP Engine have made enormous profits from selling WordPress hosting as a service (and nothing else) while making minimal to no contributions back to the open source platform that they depend upon.

If true, and it appears to be, this would violate the principle of reciprocity. If you benefit from somebody else’s effort (and you’re able to) you’re morally-obliged to at least offer to give back in a manner commensurate to your relative level of resources.

Abuse of this principle is… sadly not-uncommon in business. Or in tech. Or in the world in general. A lightweight example might be the many millions of profitable companies that host atop the Apache HTTP Server without donating a penny to the Apache Foundation. A heavier (and legally-backed) example might be Trump Social’s implementation being based on a modified version of Mastodon’s code: Mastodon’s license requires that their changes are shared publicly… but they don’t do until they’re sent threatening letters reminding them of their obligations.

I feel like it’s fair game to call out companies that act amorally, and encourage people to boycott them, so long as you do so without “punching down”.

Ethically: don’t exploit open source’s liberties as weaknesses

WP Engine also stand accused of altering the open source code that they host in ways that maximise their profit, to the detriment of both their customers and the original authors of that code5.

It’s well established, for example, that WP Engine disable the “revisions” feature of WordPress6. Personally, I don’t feel like this is as big a deal as Matt makes out that it is (I certainly wouldn’t go as far as saying “WP Engine is not WordPress”): it’s pretty commonplace for large hosting companies to tweak the open source software that they host to better fit their architecture and business model.

But I agree that it does make WordPress as-provided by WP Engine significantly less good than would be expected from virtually any other host (most of which, by the way, provide much better value-for-money at any price point).

Again, I think this is fair game to call out, even if it’s not something that anybody has a right to enforce legally. On which note…

Legally: trademarks have value, don’t steal them

Automattic Inc. has a recognised trademark on WooCommerce, and is the custodian of the WordPress Foundation’s trademark on WordPress. WP Engine are accused of unauthorised use of these trademarks.

Obviously, this is the part of the story you’re going to see the most news media about, because there’s reasonable odds it’ll end up in front of a judge at some point. There’s a good chance that such a case might revolve around WP Engine’s willingness (and encouragement?) to allow their business to be called “WordPress Engine” and to capitalise on any confusion that causes.

I’m not going to weigh in on the specifics of the legal case: I Am Not A Lawyer and all that. Naturally I agree with the underlying principle that one should not be allowed to profit off another’s intellectual property, but I’ll leave discussion on whether or not that’s what WP Engine are doing as a conversation for folks with more legal-smarts than I. I’ve certainly known people be confused by WP Engine’s name and branding, though, and think that they must be some kind of “officially-licensed” WordPress host: it happens.

If you’re following all of this drama as it unfolds… just remember to check your sources. There’s a lot of FUD floating around on the Internet right now9.

In summary…

With a reminder that I’m sharing my own opinion here and not that of my employer, here’s my thoughts on the recent WP Engine drama:

- WP Engine certainly act in ways that are unethical and immoral and antithetical to the spirit of open source, and those are just a subset of the reasons that I wouldn’t use them as a WordPress host.

- Matt Mullenweg calling them out at WordCamp US doesn’t get his point across as well as I think he hoped it might, and probably won’t win him any popularity contests.

- I’m not qualified to weigh in on whether or not WP Engine have violated the WordPress Foundation’s trademarks, but I suspect that they’ve benefitted from widespread confusion about their status.

Footnotes

1 I suppose I ought to point out that Automattic is my employer, in case you didn’t know, and point out that my opinions don’t necessarily represent theirs, etc. I’ve been involved with WordPress as an open source project for about four times as long as I’ve had any connection to Automattic, though, and don’t always agree with them, so I’d hope that it’s a given that I’m speaking my own mind!

2 Though like Manu, I don’t think that means that Matt should take the corresponding blog post down: I’m a digital preservationist, as might be evidenced by the unrepresentative-of-me and frankly embarrassing things in the 25-year archives of this blog!

3 Fortunately the documents that the lawyers for both sides have been writing are much clearer and more-specific, but that’s what you pay lawyers for, right?

4 There’s a huge amount of debate about the difference between morality and ethics, but I’m using the definition that means that morality is based on what a social animal might be expected to decide for themselves is right, think e.g. the Golden Rule etc., whereas ethics is the code of conduct expected within a particular community. Take stealing, for example, which covers the spectrum: that you shouldn’t deprive somebody else of something they need, is a moral issue; that we as a society deem such behaviour worthy of exclusion is an ethical one; meanwhile the action of incarcerating burglars is part of our legal framework.

5 Not that nobody’s immune to making ethical mistakes. Not me, not you, not anybody else. I remember when, back in 2005, Matt fucked up by injecting ads into WordPress (which at that point didn’t have a reliable source of funding). But he did the right thing by backpedalling, undoing the harm, and apologising publicly and profusely.

6 WP Engine claim that they disable revisions for performance reasons, but that’s clearly bullshit: it’s pretty obvious to me that this is about making hosting cheaper. Enabling revisions doesn’t have a performance impact on a properly-configured multisite hosting system, and I know this from personal experience of running such things. But it does have a significant impact on how much space you need to allocate to your users, which has cost implications at scale.

7 As an aside: if a court does rule that WP Engine is infringing upon WordPress trademarks and they want a new company name to give their service a fresh start, they’re welcome to TurdPress.

8 I’d argue that it is okay to do so for personal-use though: the difference for me comes when you’re making a profit off of it. It’s interesting to find these edge-cases in my own thinking!

9 A typical Reddit thread is about 25% lies-and-bullshit; but you can double that for a typical thread talking about this topic!

Calculating the Ideal “Sex and the City” Polycule

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I’ve never been even remotely into Sex and the City. But I can’t help but love that this developer was so invested in the characters and their relationships that when he asked himself “couldn’t all this drama and heartache have been simplified if these characters were willing to consider polyamorous relationships rather than serial monogamy?”1, he did the maths to optimise his hypothetical fanfic polycule:

As if his talk at !!Con 2024 wasn’t cool enough, he open-sourced the whole thing, so you’re free to try the calculator online for yourself or expand upon or adapt it to your heart’s content. Perhaps you disagree with his assessment of the relative relationship characteristics of the characters2: tweak them and see what the result is!

Or maybe Sex and the City isn’t your thing at all? Well adapt it for whatever your fandom is! How I Met Your Mother, Dawson’s Creek, Mamma Mia and The L-Word were all crying out for polyamory to come and “fix” them3.

Perhaps if you’re feeling especially brave you’ll put yourself and your circles of friends, lovers, metamours, or whatever into the algorithm and see who it matches up. You never know, maybe there’s a love connection you’ve missed! (Just be ready for the possibility that it’ll tell you that you’re doing your love life “wrong”!)

Footnotes

1 This is a question I routinely find myself asking of every TV show that presents a love triangle as a fait accompli resulting from an even moderately-complex who’s-attracted-to-whom.

2 Clearly somebody does, based on his commit “against his will” that increases Carrie and Big’s

validatesOthers scores and reduces Big’s prioritizesKindness.

3 I was especially disappointed with the otherwise-excellent The L-Word, which did have a go at an ethical non-monogamy storyline but bungled the “ethical” at every hurdle while simultaneously reinforcing the “insatiable bisexual” stereotype. Boo! Anyway: maybe on my next re-watch I’ll feed some numbers into Juan’s algorithm and see what comes out…

So… I’m A Podcast

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Observant readers might have noticed that some of my recent blog posts – like the one about special roads, my idea for pressure-cooking tea, and the one looking at the history of window tax in two countries1 – are also available as podcast.

Why?

Like my occasional video content, this isn’t designed to replace any of my blogging: it’s just a different medium for those that might prefer it.

For some stories, I guess that audio might be a better way to find out what I’ve been thinking about. Just like how the vlog version of my post about my favourite video game Easter Egg might be preferable because video as a medium is better suited to demonstrating a computer game, perhaps audio’s the right medium for some of the things I write about, too?

But as much as not, it’s just a continuation of my efforts to explore different media over which a WordPress blog can be delivered2. Also, y’know, my ongoing effort to do what I’m bad at in the hope that I might get better at a wider diversity of skills.

How?

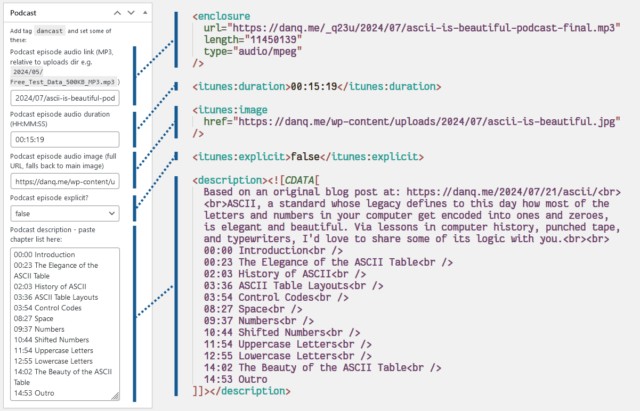

Let’s start by understanding what a “podcast” actually is. It is, in essence, just an RSS feed (something you might have heard me talk about before…) with audio enclosures – basically, “attachments” – on each item. The idea was spearheaded by Dave Winer back in 2001 as a way of subscribing to rich media like audio or videos in such a way that slow Internet connections could pre-download content so you didn’t have to wait for it to buffer.3

Here’s what I had to do to add podcasting capability to my theme:

The tag

I use a post tag, dancast, to represent posts with accompanying podcast content4.

This way, I can add all the podcast-specific metadata only if the user requests the feed of that tag, and leave my regular feeds untampered . This means that you don’t

get the podcast enclosures in the regular subscription; that might not be what everybody would want, but it suits me to serve podcasts only to people who explicitly ask for

them.

It also means that I’m able to use a template, tag-dancast.php, in my theme to generate a customised page for listing podcast episodes.

The feed

Okay, onto the code (which I’ve open-sourced over here). I’ve use a series of standard WordPress hooks to add the functionality I need. The important bits are:

-

rss2_item– to add the<enclosure>,<itunes:duration>,<itunes:image>, and<itunes:explicit>elements to the feed, when requesting a feed with my nominated tag. Only<enclosure>is strictly required, but appeasing Apple Podcasts is worthwhile too. These are lifted directly from the post metadata. -

the_excerpt_rss– I have another piece of post metadata in which I can add a description of the podcast (in practice, a list of chapter times); this hook swaps out the existing excerpt for my custom one in podcast feeds. -

rss_enclosure– some podcast syndication platforms and players can’t cope with RSS feeds in which an item has multiple enclosures, so as a safety precaution I strip out any enclosures that WordPress has already added (e.g. the featured image). -

the_content_feed– my RSS feed usually contains the full text of every post, because I don’t like feeds that try to force you to go to the original web page5 and I don’t want to impose that on others. But for the podcast feed, the text content of the post is somewhat redundant so I drop it. -

rss2_ns– of critical importance of course is adding the relevant namespaces to your XML declaration. I use theitunesnamespace, which provides the widest compatibility for specifying metadata, but I also use the newerpodcastnamespace, which has growing compatibility and provides some modern features, most of which I don’t use except specifying a license. There’s no harm in supporting both. -

rss2_head– here’s where I put in the metadata for the podcast as a whole: license, category, type, and so on. Some of these fields are effectively essential for best support.

You’re welcome, of course, to lift any of all of the code for your own purposes. WordPress makes a perfectly reasonable platform for podcasting-alongside-blogging, in my experience.

What?

Finally, there’s the question of what to podcast about.

My intention is to use podcasting as an alternative medium to my traditional blog posts. But not every blog post is suitable for conversion into a podcast! Ones that rely on images (like my post about dithering) aren’t a great choice. Ones that have lots of code that you might like to copy-and-paste are especially unsuitable.

Also: sometimes I just can’t be bothered. It’s already some level of effort to write a blog post; it’s like an extra 25% effort on top of that to record, edit, and upload a podcast version of it.

That’s not nothing, so I’ve tended to reserve podcasts for blog posts that I think have a sort-of eccentric “general interest” vibe to them. When I learn something new and feel the need to write a thousand words about it… that’s the kind of content that makes it into a podcast episode.

Which is why I’ve been calling the endeavour “a podcast nobody asked for, about things only Dan Q cares about”. I’m capable of getting nerdsniped easily and can quickly find my way down a rabbit hole of learning. My podcast is, I guess, just a way of sharing my passion for trivial deep dives with the rest of the world.

My episodes are probably shorter than most podcasts: my longest so far is around fifteen minutes, but my shortest is only two and a half minutes and most are about seven. They’re meant to be a bite-size alternative to reading a post for people who prefer to put things in their ears than into their eyes.

Anyway: if you’re not listening already, you can subscribe from here or in your favourite podcasting app. Or you can just follow my blog as normal and look for a streamable copy of podcasts at the top of selected posts (like this one!).

Footnotes

1 I’ve also retroactively recorded a few older ones. Have a look/listen!

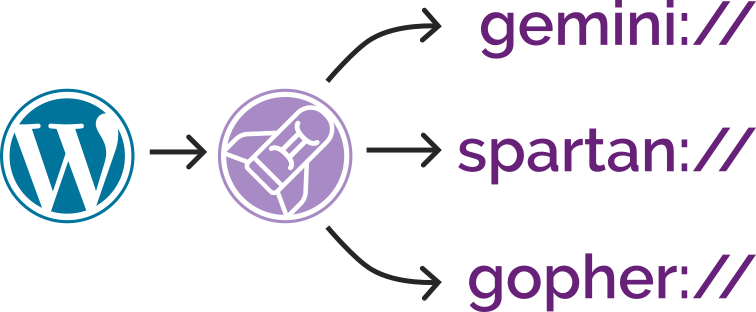

2 As well as Web-based non-textual content like audio (podcasts) and video (vlogs), my blog is wholly or partially available over a variety of more-exotic protocols: did you find me yet on Gemini (gemini://danq.me/), Spartan (spartan://danq.me/), Gopher (gopher://danq.me/), and even Finger

(finger://danq.me/, or run e.g. finger blog@danq.me from your command line)? Most of these are powered by my very own tool CapsulePress, and I’m itching to try a few more… how about a WordPress blog that’s accessible over FTP, NNTP, or DNS? I’m not even kidding when I say

I’ve got ideas for these…

3 Nowadays, we have specialised media decoder co-processors which reduce the size of media files. But more-importantly, today’s high-speed always-on Internet connections mean that you probably rarely need to make a conscious choice between streaming or downloading.

4 I actually intended to change the tag to podcast when I went-live,

but then I forgot, and now I can’t be bothered to change it. It’s only for my convenience, after all!

5 I’m very grateful that my favourite feed reader makes it possible to, for example, use a CSS selector to specify the page content it should pre-download for you! It means I get to spend more time in my feed reader.

Draw Me a Comment!

Why must a blog comment be text? Why could it not be… a drawing?1

I started hacking about and playing with a few ideas and now, on selected posts including this one, you can draw me a comment instead of typing one.

I opened the feature, experimentally (in a post available only to RSS subscribers2) the other week, but now you get a go! Also, I’ve open-sourced the whole thing, in case you want to pick it apart.

What are you waiting for: scroll down, and draw me a comment!

Footnotes

1 I totally know the reasons that a blog comment shouldn’t be a drawing; I’m not completely oblivious. Firstly, it’s less-expressive: words are versatile and you can do a lot with them. Secondly, it’s higher-bandwidth: images take up more space, take longer to transmit, and that effect compounds when – like me – you’re tracking animation data too. But the single biggest reason, and I can’t stress this enough, is… the penises. If you invite people to draw pictures on your blog, you’re gonna see a lot of penises. Short penises, long penises, fat penises, thin penises. Penises of every shape and size. Some erect and some flacid. Some intact and some circumcised. Some with hairy balls and some shaved. Many of them urinating or ejaculating. Maybe even a few with smiley faces. And short of some kind of image-categorisation AI thing, you can’t realistically run an anti-spam tool to detect hand-drawn penises.

2 I’ve copied a few of my favourites of their drawings below. Don’t forget to subscribe if you want early access to any weird shit I make.

Tidying WordPress’s HTML

Terence Eden, who’s apparently inspiring several posts this week, recently shared a way to attach a hook to WordPress’s

get_the_post_thumbnail() function in order to remove the extraneous “closing mark” from the (self-closing in HTML) <img> element.

By default, WordPress outputs e.g. <img src="..." />, where <img src="..."> would suffice.

It’s an inconsequential difference for most purposes, but apparently it bugs him, so he fixed it… although he went on to observe that he hadn’t managed to successfully tackle all the instances in which WordPress was outputting redundant closing marks.

This is a problem that I’ve already solved here on my blog. My solution’s slightly hacky… but it works!

/>s” isn’t among them.

My Solution: Runing HTMLTidy over WordPress

Tidy is an excellent tool for tiding up HTML! I used to use its predecessor back in the day for all kind of things, but it languished for a few years and struggled with support for modern HTML features. But in 2015 it made a comeback and it’s gone from strength to strength ever since.

I run it on virtually all pages produced by DanQ.me (go on, click “View Source” and see for yourself!), to:

- Standardise the style of the HTML code and make it easier for humans to read1.

- Bring old-style emphasis tags like

<i>, in my older posts, into a more-modern interpretation, like<em>. - Hoist any inline

<style>blocks to the<head>, and detect any repeated inlinestyle="..."s to convert to classes. - Repair any invalid HTML (browsers do this for you, of course, but doing it server-side makes parsing easier for the browser, which might matter on more-lightweight hardware).

WordPress isn’t really designed to have Tidy bolted onto it, so anything it likely to be a bit of a hack, but here’s my approach:

-

Install

libtidy-devand build the PHP bindings to it.

Note that if you don’t do this the code might appear to work, but it won’t actually tidy anything2. -

Add a new output buffer to my theme’s

header.php3, with a callback function:ob_start('tidy_entire_page').

Without an correspondingob_flushor similar, this buffer will close and the function will be called when PHP finishes generating the page. -

Define the

function tidy_entire_page($buffer)

Have it instantiate Tidy ($tidy = new tidy) and use$tidy->parseString(with your buffer and Tidy preferences) to tidy the code, thenreturn $tidy. -

Ensure that you’re caching the results!

You don’t want to run this every page load for anonymous users! WP Super Cache on “Expert” mode (with the requisite webserver configuration) might help.

I’ve open-sourced a demonstration that implements a child theme to TwentyTwentyOne to do this: there’s a richer set of instructions in the repo’s readme. If you want, you can run my example in Docker and see for yourself how it works before you commit to trying to integrate it into your own WordPress installation!

Footnotes

1 I miss the days when most websites were handwritten and View Source typically looked nice. It was great to learn from, too, especially in an age before we had DOM debuggers. Today: I can’t justify dropping my use of a CMS, but I can make my code readable.

2 For a few of its extensions, some PHP developer made the interesting choice to fail silently if the required extension is missing. For example: if you don’t have the

zip extension enabled you can still use PHP to make ZIP files, but they won’t be

compressed. This can cause a great deal of confusion for developers! A similar issue exists with tidy: if it isn’t installed, you can still call all of the

methods on it… they just don’t do anything. I can see why this decision might have been made – to make the language as portable as possible in production – but I’d

prefer if this were an optional feature, e.g. you had to set try_to_make_do_if_you_are_missing_an_extension=yes in your php.ini to enable it, or if

it at least logged that it had done so.

3 My approach probably isn’t suitable for FSE (“block”) themes, sorry.

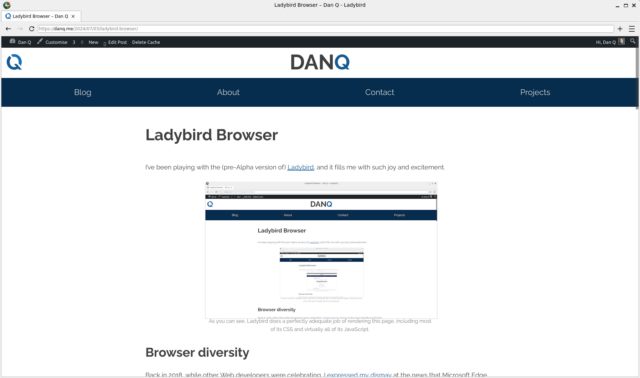

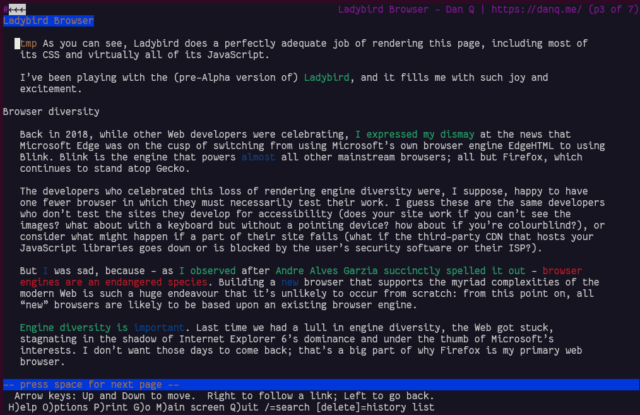

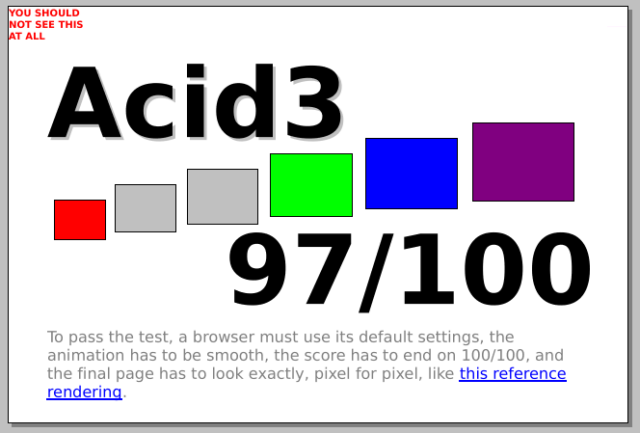

Ladybird Browser

I’ve been playing with the (pre-Alpha version of) Ladybird, and it fills me with such joy and excitement.

Browser diversity

Back in 2018, while other Web developers were celebrating, I expressed my dismay at the news that Microsoft Edge was on the cusp of switching from using Microsoft’s own browser engine EdgeHTML to using Blink. Blink is the engine that powers almost all other mainstream browsers; all but Firefox, which continues to stand atop Gecko.

The developers who celebrated this loss of rendering engine diversity were, I suppose, happy to have one fewer browser in which they must necessarily test their work. I guess these are the same developers who don’t test the sites they develop for accessibility (does your site work if you can’t see the images? what about with a keyboard but without a pointing device? how about if you’re colourblind?), or consider what might happen if a part of their site fails (what if the third-party CDN that hosts your JavaScript libraries goes down or is blocked by the user’s security software or their ISP?).

But I was sad, because – as I observed after Andre Alves Garzia succinctly spelled it out – browser engines are an endangered species. Building a new browser that supports the myriad complexities of the modern Web is such a huge endeavour that it’s unlikely to occur from scratch: from this point on, all “new” browsers are likely to be based upon an existing browser engine.

Engine diversity is important. Last time we had a lull in engine diversity, the Web got stuck, stagnating in the shadow of Internet Explorer 6’s dominance and under the thumb of Microsoft’s interests. I don’t want those days to come back; that’s a big part of why Firefox is my primary web browser.

A Ladybird book browser

Ladybird is a genuine new browser engine. Y’know, that thing I said that we might never see happen again! So how’ve they made it happen?

It helps that it’s not quite starting from scratch. It’s starting point is the HTML viewer component from SerenityOS. And… it’s pretty good. It’s DOM processing’s solid, it seems to support enough JavaScript and CSS that the modern Web is usable, even if it’s not beautiful 100% of the time.

They’re not even expecting to make an Alpha release until next year! Right now if you want to use it at all, you’re going to need to compile the code for yourself and fight with a plethora of bugs, but it works and that, all by itself, is really exciting.

They’ve got four full-time engineers, funded off donations, with three more expected to join, plus a stack of volunteer contributors on Github. I’ve raised my first issue against the repo; sadly my C++ probably isn’t strong enough to be able to help more-directly, even if I somehow did have enough free time, which I don’t. But I’ll be watching-from-afar this wonderful, ambitious, and ideologically-sound initiative.

#100DaysToOffload

Woop! This is my 100th post of the year (stats), even using my more-conservative/pedant-friendly “don’t count checkins/reposts/etc. rule. If you’re not a pedant, I achieved #100DaysToOffload when I found a geocache alongside Regents Canal while changing trains to go to Amsterdam where I played games with my new work team, looked at windows and learned about how they’ve been taxed, and got nerdsniped by a bus depot. In any case: whether you’re a pedant or not you’ve got to agree I’ve achieved it now!

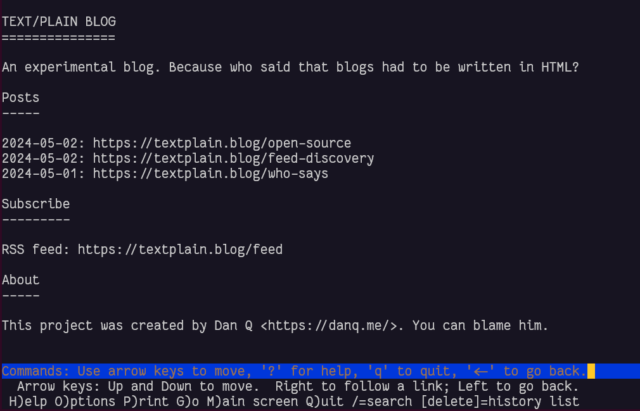

Does a blog have to be HTML?

Terence Eden wrote about his recent experience of IndieWebCamp Brighton, in which he mentioned that somebody – probably Jeremy Keith – had said, presumably to provoke discussion:

A blog post doesn’t need a title.

Terence disagrees, saying:

In a literal sense, he was wrong. The HTML specification makes it clear that the

<title>element is mandatory. All documents have title.

But I think that’s an overreach. After all, where is it written that a blog must be presented in HTML?

Non-HTML blogs

There are plenty of counter-examples already in existence, of course:

- Terence’s own no-ht.ml (now offline) demonstrated that a website needn’t use HTML1. This inspired my own “page with no code”, which worked by hiding content in CSS and loading the CSS using HTTP headers2.

-

theunderground.blog‘s content, with the exception of its homepage, is delivered entirely through an XML Atom feed. Atom feed entries do require

<title>s, of course, so that’s not the strongest counterexample! -

This blog is available over several media other than the Web. For example, you can read this blog post:

- in Gemtext3

- via Gemini at gemini://danq.me/posts/does-a-blog-have-to-be-html

- via Spartan at spartan://danq.me/posts/does-a-blog-have-to-be-html

- in plain text4

- via Gopher at gopher://danq.me/1/posts/does-a-blog-have-to-be-html

- via Finger at finger://does-a-blog-have-to-be-html@danq.me

- in Gemtext3

But perhaps we can do better…

A totally text/plain blog

We’ve looked at plain text, which as a format clearly does not have to have a title. Let’s go one step further and implement it. What we’d need is:

- A webserver configured to deliver plain text files by preference, e.g. by adding directives like

index index.txt;(for Nginx).5 - An index page listing posts by date and URL. Most browser won’t render these as “links” so users will have to copy-paste or re-type them, so let’s keep them short,

- Pages for each post at those URLs, presumably without any kind of “title” (just to prove a point), and

- An RSS feed: usually I use RSS as shorthand for all feed

types, but this time I really do mean RSS and not e.g. Atom because RSS, strangely, doesn’t require that an

<item>has a<title>!

I’ve implemented it! it’s at textplain.blog.

In the end I decided it’d benefit from being automated as sort-of a basic flat-file CMS, so I wrote it in PHP. All requests are routed by the webserver to the program, which determines whether they’re a request for the homepage, the RSS feed, or a valid individual post, and responds accordingly.

It annoys me that feed

discovery doesn’t work nicely when using a Link: header, at least not in any reader I tried. But apart from that, it seems pretty solid, despite its limitations. Is this,

perhaps, an argument for my .well-known/feeds proposal?

Anyway, I’ve open-sourced the entire thing in case it’s of any use to anybody at all, which is admittedly unlikely! Here’s the code.

Footnotes

1 no-ht.ml technically does use HTML, but the same content could easily be delivered with an appropriate non-HTML MIME type if he’d wanted.

2 Again, I suppose this technically required HTML, even if what was delivered was an empty file!

3 Gemtext is basically Markdown, and doesn’t require a title.

4 Plain text obviously doesn’t require a title.

5 There’s no requirement that default files served by webservers are HTML, although it’s highly-unsual for that not to be the case.

BBC News… without the crap

Update: nowadays, the best place to get this feed and more like it is at bbc-feeds.danq.dev.

Did I mention recently that I love RSS? That it brings me great joy? That I start and finish almost every day in my feed reader? Probably.

I used to have a single minor niggle with the BBC News RSS feed: that it included sports news, which I didn’t care about. So I wrote a script that downloaded it, stripped sports news, and re-exported the feed for me to subscribe to. Magic.

But lately – presumably as a result of technical changes at the Beeb’s side – this feed has found two fresh ways to annoy me:

-

The feed now re-publishes a story if it gets re-promoted to the front page… but with a different

<guid>(it appears to get a #0 after it when first published, a #1 the second time, and so on). In a typical day the feed reader might scoop up new stories about once an hour, any by the time I get to reading them the same exact story might appear in my reader multiple times. Ugh. - They’ve started adding iPlayer and BBC Sounds content to the BBC News feed. I don’t follow BBC News in my feed reader because I want to watch or listen to things. If you do, that’s fine, but I don’t, and I’d rather filter this content out.

Luckily, I already have a recipe for improving this feed, thanks to my prior work. Let’s look at my newly-revised script (also available on GitHub):

#!/usr/bin/env ruby require 'bundler/inline' # # Sample crontab: # # At 41 minutes past each hour, run the script and log the results # */20 * * * * ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.rb > ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.log 2>>&1 # Dependencies: # * open-uri - load remote URL content easily # * nokogiri - parse/filter XML gemfile do source 'https://rubygems.org' gem 'nokogiri' end require 'open-uri' # Regular expression describing the GUIDs to reject from the resulting RSS feed # We want to drop everything from the "sport" section of the website, also any iPlayer/Sounds links REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING = /^https:\/\/www\.bbc\.co\.uk\/(sport|iplayer|sounds)\// # Load and filter the original RSS rss = Nokogiri::XML(open('https://feeds.bbci.co.uk/news/rss.xml?edition=uk')) rss.css('item').select{|item| item.css('guid').text =~ REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING }.each(&:unlink) # Strip the anchors off the <guid>s: BBC News "republishes" stories by using guids with #0, #1, #2 etc, which results in duplicates in feed readers rss.css('guid').each{|g|g.content=g.content.gsub(/#.*$/,'')} File.open( '/www/bbc-news-no-sport.xml', 'w' ){ |f| f.puts(rss.to_s) }

That revised script removes from the feed anything whose <guid> suggests it’s sports news or from BBC Sounds or iPlayer, and also strips any “anchor” part of the

<guid> before re-exporting the feed. Much better. (Strictly speaking, this can result in a technically-invalid feed by introducing duplicates, but your feed reader

oughta be smart enough to compensate for and ignore that: mine certainly is!)

You’re free to take and adapt the script to your own needs, or – if you don’t mind being tied to my opinions about what should be in BBC News’ RSS feed – just subscribe to my copy at: https://fox.q-t-a.uk/bbc-news-no-sport.xml

Update: nowadays, the best place to get this feed and more like it is at bbc-feeds.danq.dev.

Open Turds

I’ve open-sourced a lot of pretty shit code.

So whenever somebody says “I’m not open-sourcing this because the code is shit”, I think: wow, it must be spectacularly bad.

And that only makes me want to see it more.

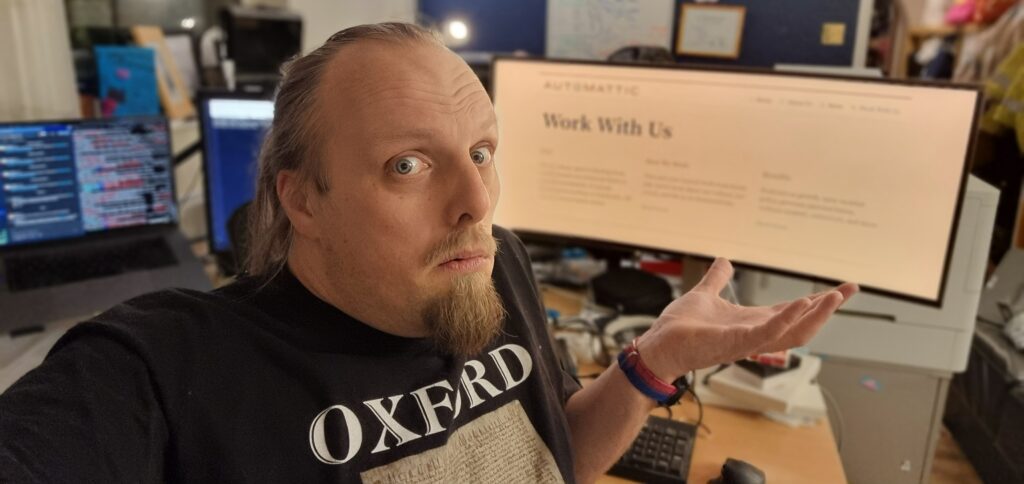

Automattic Shakeup

My employer Automattic‘s having a bit of a reorganisation. For unrelated reasons, this coincides with my superteam having a bit of a reorganisation, too, and I’m going to be on a different team next week than I’ve been on for most of the 4+ years I’ve been there1. Together, these factors mean that I have even less idea than usual what I do for a living, right now.

On the whole, I approve of Matt‘s vision for this reorganisation. He writes:

Each [Automattic employee] gets a card: Be the Host, Help the Host, or Neutral.

You cannot change cards during the course of your day or week. If you do not feel aligned with your card, you need to change divisions within Automattic.

“Be the Host” folks are all about making Automattic’s web hosting offerings the best they possibly can be. These are the teams behind WordPress.com, VIP, and Tumblr, for example. They’re making us competitive on the global stage. They bring Automattic money in a very direct way, by making our (world class) hosting services available to our customers.

“Help the Host” folks (like me) are in roles that are committed to providing the best tools that can be used anywhere. You might run your copy of Woo, Jetpack, or (the client-side bit of) Akismet on Automattic infrastructure… or alternatively you might be hosted by one of our competitors or even on your own hardware. What we bring to Automattic is more ethereal: we keep the best talent and expertise in these technologies close to home, but we’re agnostic about who makes money out of what we create.

Anyway: I love the clarification on the overall direction of the company… but I’m not sure how we market it effectively2. I look around at the people in my team and its sister teams, all of us proudly holding our “Help the Hosts” cards and ready to work to continue to make Woo an amazing ecommerce platform wherever you choose to host it.

And obviously I can see the consumer value in that. It’s reassuring to know that the open source software we maintain or contribute to is the real deal and we’re not exporting a cut-down version nor are we going to try to do some kind of rug pull to coerce people into hosting with us. I think Automattic’s long track record shows that.

But how do we sell that? How do we explain that “hey, you can trust us to keep these separate goals separate within our company, so there’s never a conflict of interest and you getting the best from us is always what we want”? Personally, seeing the inside of Automattic, I’m convinced that we’re not – like so much of Big Tech – going to axe the things you depend upon3 or change the terms and conditions to the most-exploitative we can get away with4 or support your business just long enough to be able to undermine and consume it 5.

In short: I know that we’re the “good guys”. And I can see how this reorganisation reinforces that. But I can’t for the life of me see how we persuade the rest of the world of the fact6.

Any ideas?

Footnotes

1 I’ve been on Team Fire for a long while, which made my job title “Code Magician on Fire”, but now I’ll be on Team Desire which isn’t half as catchy a name but I’m sure they’ll make up for it by being the kinds of awesome human beings I’ve become accustomed to working alongside at Automattic.

2 Fortunately they pay me to code, not to do marketing.

3 Cough… Google.

4 Ahem… Facebook.

5 ${third_coughing_sound}… Amazon.

6 Seriously, it’s a good thing I’m not in marketing. I’d be so terrible at it. Also public relations. Did I ever tell you the story about the time that, as a result of a mix-up, I accidentally almost gave an interview to the Press Office at the Vatican? A story for another time, perhaps

[Bloganuary] Fun Five

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

List five things you do for fun.

This feels disappointingly like the prompt from day 2, but I’m gonna pivot it by letting my answer from three weeks ago only cover one of the five points:

- Code

- Magic

- Piano

- Play

- Learn

Let’s take a look at each of those, briefly.

Code

Code is poetry. Code is fun. Code is a many-splendoured thing.

When I’m not coding for work or coding as a volunteer, I’m often caught coding for fun. Sometimes I write WordPress-ey things. Sometimes I write other random things. I tend to open-source almost everything I write, most of it via my GitHub account.

Magic

Now I don’t work in the city centre nor have easy access to other magicians, I don’t perform as much magic as I used to. But I still try to keep my hand in and occasionally try new things; I enjoy practicing sleights when I’m doing work-related things that don’t require my hands (meetings, code reviews, waiting for the damn unit tests to run…), a tip I learned from fellow magician Andy.

You’ll usually find a few decks of cards on my desk at any given time, mostly Bikes.1

Piano

I started teaching myself piano during the Covid lockdowns as a distraction from not being able to go anywhere (apparently I’m not the only one), and as an effort to do more of what I’m bad at.2 Since then, I’ve folded about ten minutes of piano-playing3, give or take, into my routine virtually every day.

I fully expect that I’ll never be as accomplished at it as, say, the average 8-year-old on YouTube, but that’s not what it’s about. If I take a break from programming, or meetings, or childcare, or anything, I can feel that playing music exercises a totally different part of my mind. I’d heard musicians talk about such an experience before, but I’d assumed that it was hyperbole… but from my perspective, they’re right: practicing an instrument genuinely does feel like using a part of your brain than you use for anything else, which I love!

Play

I wrote a whole other Bloganuary post on the ways in which I integrate “play” into my life, so I’ll point you at that rather than rehash anything.

At the weekend I dusted off Vox Populi, my favourite mod for Civilization V, my favourite4 entry in the Civilization series, which in turn is one of my favourite video game series5. I don’t get as much time for videogaming as I might like, but that’s probably for the best because a couple of hours disappeared on Sunday evening before I even blinked! It’s addictive stuff.

Learn

As I mentioned back on day 3 of bloganuary, I’m a lifelong learner. But even when I’m not learning in an academic setting, I’m doubtless learning something. I tend to alternate between fiction and non-fiction books on my bedside table. I often get lost on deep-dives through the depths of the Web after a Wikipedia article makes me ask “wait, really?” And just sometimes, I set out to learn some kind of new skill.

In short: with such a variety of fun things lined-up, I rarely get the opportunity to be bored6!

Footnotes

1 I like the feel of Bicycle cards and the way they fan. Plus: the white border – which is actually a security measure on playing cards designed to make bottom-dealing more-obvious and thus make it harder for people to cheat at e.g. poker – can actually be turned to work for the magician when doing certain sleights, including one seen in the mini-video above…

2 I’m not strictly bad at it, it’s just that I had essential no music tuition or instrument experience whatsoever – I didn’t even have a recorder at primary school! – and so I was starting at square zero.

3 Occasionally I’ll learn a bit of a piece of music, but mostly I’m trying to improve my ability to improvise because that scratches an itch in a part of my brain in a way that I find most-interesting!

4 Games in the series I’ve extensively played include: Civilization, CivNet, Civilization II (also Test of Time), Alpha Centauri (a game so good I paid for it three times, despite having previously pirated it), Civilization III, Civilization IV, Civilization V, Beyond Earth (such a disappointment compared to SMAC) and Civilization VI, plus all their expansions except for the very latest one for VI. Also spinoffs/clones FreeCiv, C-Evo, and both Call to Power games. Oh, and at least two of the board games. And that’s just the ones I’ve played enough to talk in detail about: I’m not including things like Revolution which I played an hour of and hated so much I shan’t touch it again, nor either version of Colonization which I’m treating separately…

5 Way back in 2007 I identified Civilization as the top of the top 10 videogames that stole my life, and frankly that’s still true.

6 At least, not since the kids grew out of Paw Patrol so I don’t have to sit with them and watch it any more!

CapsulePress – Gemini / Spartan / Gopher to WordPress bridge

For a while now, this site has been partially mirrored via the Gemini1 and Gopher protocols.2 Earlier this year I presented hacky versions of the tools I’d used to acieve this (and made people feel nostalgic).

Now I’ve added support for Spartan3 too and, seeing as the implementations shared functionality, I’ve combined all three – Gemini, Spartan, and Gopher – into a single package: CapsulePress.

CapsulePress is a Gemini/Spartan/Gopher to WordPress bridge. It lets you use WordPress as a CMS for any or all of those three non-Web protocols in addition to the Web.

For example, that means that this post is available on all of:

- my weblog, at https://danq.me/2023/09/10/capsulepress,

- my gemlog, at gemini://danq.me/posts/capsulepress,

- my spartanlog, at spartan://danq.me/posts/capsulepress, and

- my goperhole, at gopher://danq.me/1/posts/capsulepress

It’s also possible to write posts that selectively appear via different media: if I want to put something exclusively on my gemlog, I can, by assigning metadata that tells WordPress to suppress a post but still expose it to CapsulePress. Neat!

I’ve open-sourced the whole thing under a super-permissive license, so if you want your own WordPress blog to “feed” your Gemlog… now you can. With a few caveats:

- It’s hard to use. While not as hacky as the disparate piles of code it replaced, it’s still not the cleanest. To modify it you’ll need a basic comprehension of all three protocols, plus Ruby, SQL, and sysadmin skills.

- It’s super opinionated. It’s very much geared towards my use case. It’s improved by the use of templates. but it’s still probably only suitable for this site for the time being, until you make changes.

- It’s very-much unfinished. I’ve got a growing to-do list, which should be a good clue that it’s Not Finished. Maybe it never will but. But there’ll be changes yet to come.

Whether or not your WordPress blog makes the jump to Geminispace4, I hope you’ll came take a look at mine at one of the URLs linked above, and then continue to explore.

If you’re nostalgic for the interpersonal Internet – or just the idea of it, if you’re too young to remember it… you’ll find it there. (That Internet never actually went away, but it’s harder to find on today’s big Web than it is on lighter protocols.)

Footnotes

2 Also via Finger (but that’s another story).