I was chatting with a fellow web developer recently and made a joke about the HTML <blink> and

<marquee> tags, only to discover that he had no idea what I was talking about. They’re a part of web history that’s fallen off the radar and younger developers are

unlikely to have ever come across them. But for a little while, back in the 90s, they were a big deal.

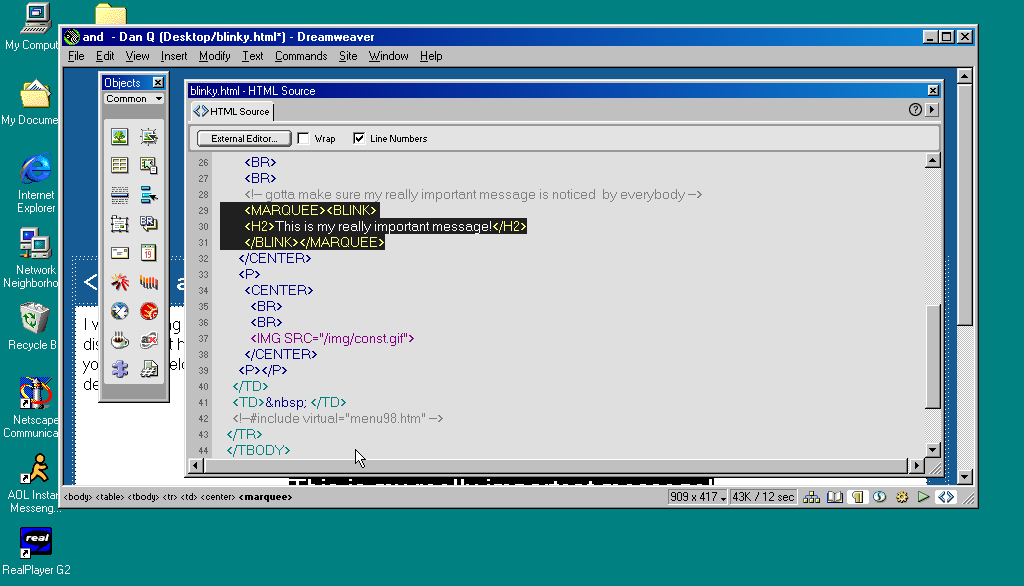

<blink> in <marquee> as an antipattern.

Invention of the <blink> element is often credited to Lou Montulli, who wrote pioneering web browser Lynx before being joining Netscape in 1994. He insists that he didn’t write any

of the code that eventually became the first implementation of <blink>. Instead, he claims: while out at a bar (on the evening he’d first meet his wife!), he

pointed out that many of the fancy new stylistic elements the other Netscape engineers were proposing wouldn’t work in Lynx, which is a text-only browser. The fanciest conceivable

effect that would work across both browsers would be making the text flash on and off, he joked. Then another engineer – who he doesn’t identify – pulled a late night hack session and

added it.

And so it was that when Netscape Navigator 2.0 was released in 1995 it added support for

the <blink> tag. Also animated GIFs and the first inklings of JavaScript, which collectively

would go on to define the “personal website” experience for years to come. Here’s how you’d use it:

<BLINK>This is my blinking text!</BLINK>

With no attributes, it was clear from the outset that this tag was supposed to be a joke. By the time HTML4 was

published as a a recommendation two years later, it was documented as being a joke. But the Web of the late 1990s

saw it used a lot. If you wanted somebody to notice the “latest updates” section on your personal home page, you’d wrap a <blink> tag around the title (or,

if you were a sadist, the entire block).

In the same year as Netscape Navigator 2.0 was released, Microsoft released Internet Explorer

2.0. At this point, Internet Explorer was still very-much playing catch-up with the features the Netscape team had implemented, but clearly some senior Microsoft engineer took a

look at the <blink> tag, refused to play along with the joke, but had an innovation of their own: the <marquee> tag! It had a whole suite of attributes to control the scroll direction, speed, and whether it looped or bounced backwards and forwards. While

<blink> encouraged disgusting and inaccessible design as a joke, <marquee> did it on purpose.

<MARQUEE>Oh my god this still works in most modern browsers!</MARQUEE>

But here’s the interesting bit: for a while in the late 1990s, it became a somewhat common practice to wrap content that you wanted to emphasise with animation in both a

<blink> and a <marquee> tag. That way, the Netscape users would see it flash, the IE users

would see it scroll or bounce. Like this:

<MARQUEE><BLINK>This is my really important message!</BLINK></MARQUEE>

<blink> inside a <marquee> and IE users will see the marquee. Delightful.

The web has always been built on Postel’s Law: a web browser should assume that it won’t understand everything it reads,

but it should provide a best-effort rendering for the benefit of its user anyway. Ever wondered why the modern <video> element is a block rather than a self-closing

tag? It’s so you can embed within it code that an earlier browser – one that doesn’t understand <video> – can read (a browser’s default state when seeing a

new element it doesn’t understand is to ignore it and carry on). So embedding a <blink> in a <marquee> gave you the best of both worlds, right?

(welll…)

<blink> inside a <marquee> and Netscape users will see the blink. Joy.

Better yet, you were safe in the knowledge that anybody using a browser that didn’t understand either of these tags could still read your content. Used properly, the web is about progressive enhancement. Implement for everybody, enhance for those who support the shiny features. JavaScript and CSS can be applied with the same rules, and doing so pays dividends in maintainability and accessibility (though, sadly, that doesn’t stop people writing sites that needlessly require these technologies).

<blink> nor <marquee> elements.

I don’t feel like I missed out.

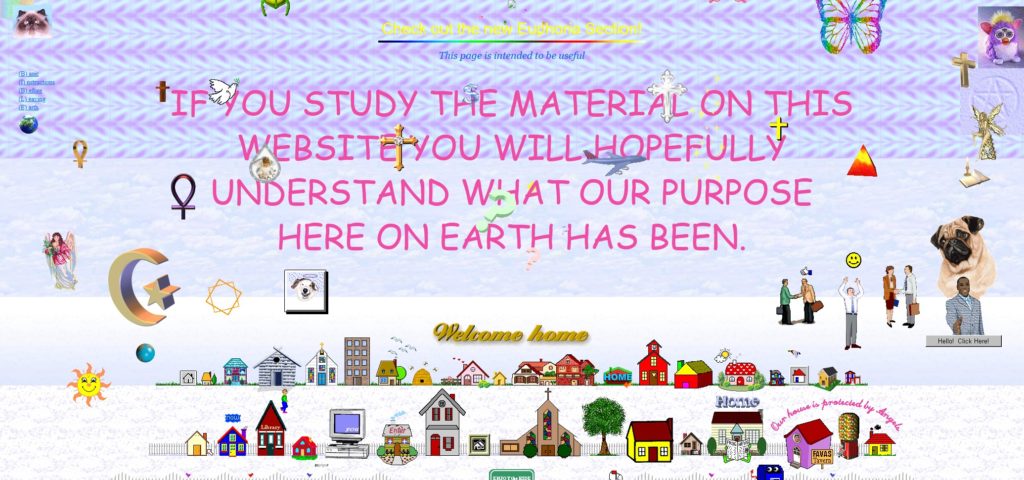

I remember, though, the first time I tried Netscape 7, in 2002. Netscape 7 and its close descendent are, as far as I can tell, the only web browsers to support both

<blink> and <marquee>. Even then, it was picky about the order in which they were presented and the elements wrapped-within them. But support was

good enough that some people’s personal web pages suddenly began to exhibit the most ugly effect imaginable: the combination of both scrolling and flashing text.

<blink> and <marquee> would.

The <blink> tag is very-definitely dead (hurrah!), but you can bring it back with pure CSS if you must.

<marquee>, amazingly, still survives, not only in polyfills but natively, as you might be able to see above. However, if you’re in any doubt as to whether or not

you should use it: you shouldn’t. If you’re looking for digital nostalgia, there’s a whole

rabbit hole to dive down, but you don’t need to inflict <marquee> on the rest of us.

0 comments