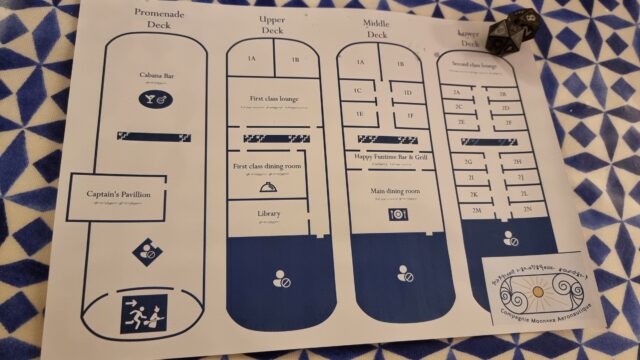

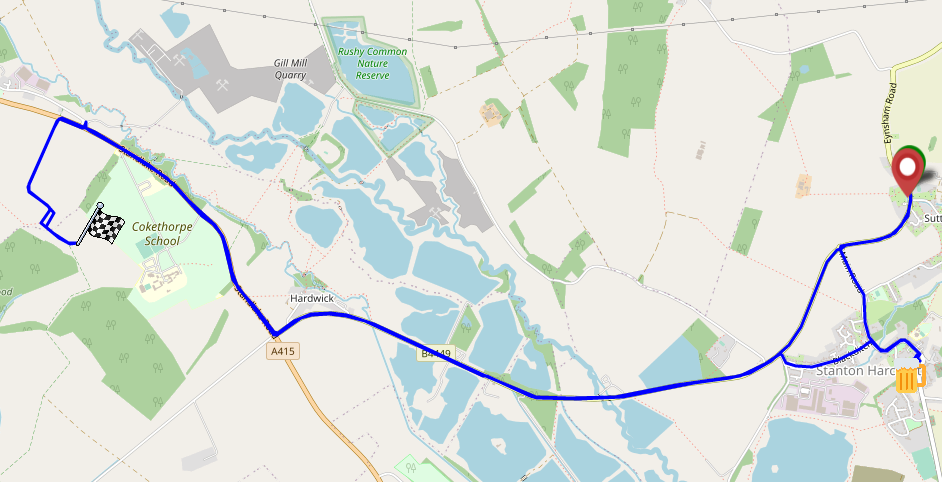

I nerdsniped myself today when, during a discussion on the potential location of a taekwondo tournament organised by our local martial arts school, somebody claimed that Scotland would be “nearer” than Ireland.

But the question got me thinking:

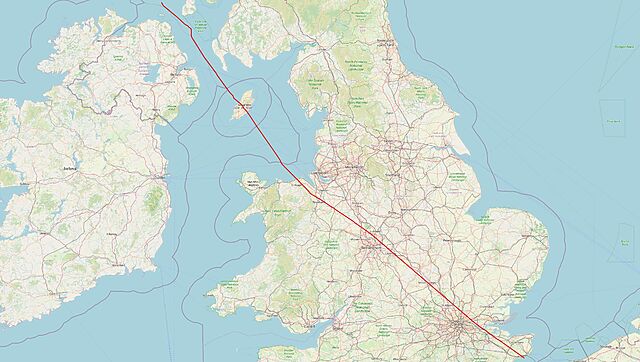

Could I plot a line across Great Britain, showing which parts are closer to Scotland and which parts are closer to Ireland?

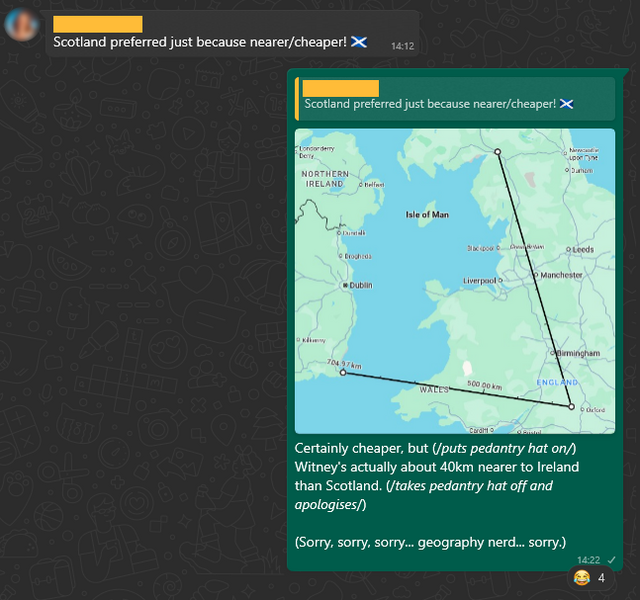

If the England-facing Irish and Scottish borders were completely straight, one could simply extend the borders until they meet, bisect the angle, and we’d be done.

In reality, the border between England and Scotland is a winding mess, shaped by 700 years of wars and treaties1. Treating the borders as straight lines is hopelessly naive.

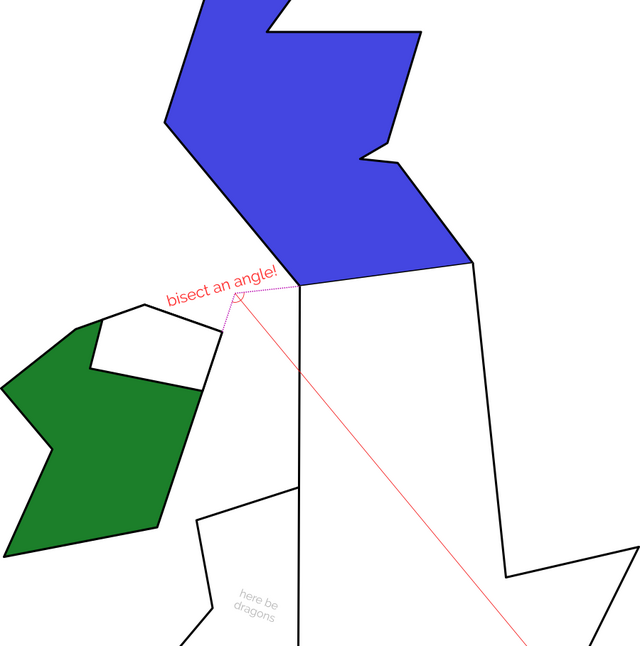

What I’m really looking for… is a Voronoi partition…

My Python skills are pretty shit, but it’s the best tool for the job for geohacking2. And so, through a combination of hacking, tweaking, and crying, I was able to throw together a script that produces a wonderful slightly-wiggly line up the country.

Once you’ve bisected England in this way – into parts that are “closer to Ireland” versus parts that are “closer to Scotland”, you start to spot all kinds of interesting things3.

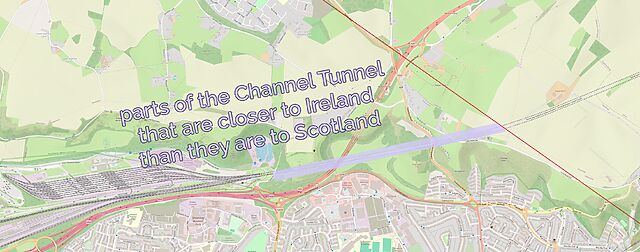

Like: did you know that the entire subterranean part of the Channel Tunnel is closer to Scotland than it is to Ireland… except for the ~2km closest to the UK exit.

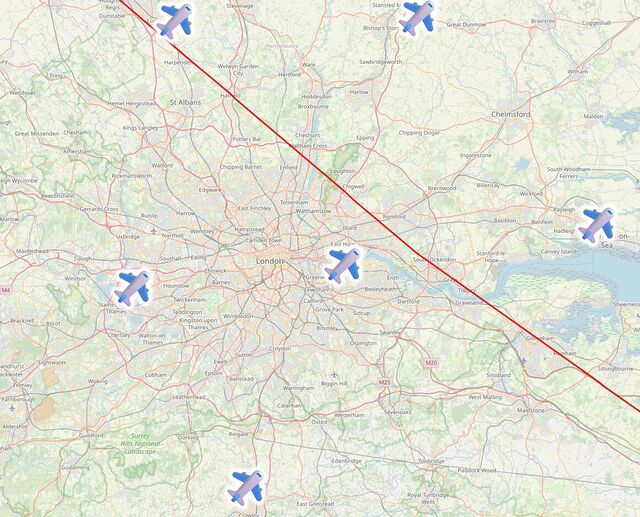

A little further North: London’s six international airports are split evenly across the line, with Luton, Stansted and Southend closer to Scotland… and City, Heathrow and Gatwick closer to Ireland.

The line then pretty-much bisects Milton Keynes, leaving half its population closer to Scotland and half closer to Ireland, before doing the same to Daventry, before – near Sutton Coldfield – it drives right through the middle of the ninth hole of the golf course at the Lea Marston Hotel.

Players tee off closer to Ireland and – unless they really slice it – their ball lands closer to Scotland:

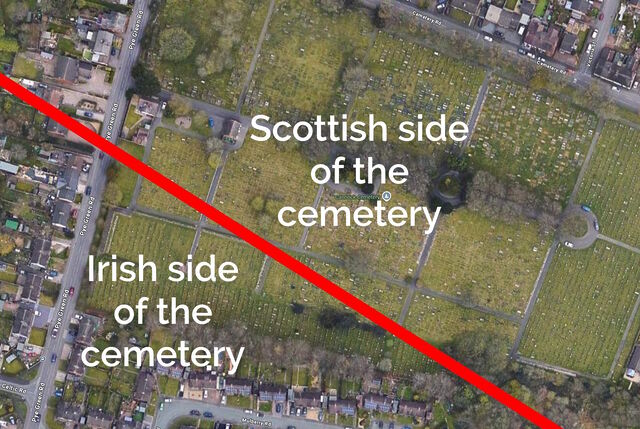

In Cannock, it bisects the cemetery, dividing the graves into those on the Scottish half and those in the Irish half:

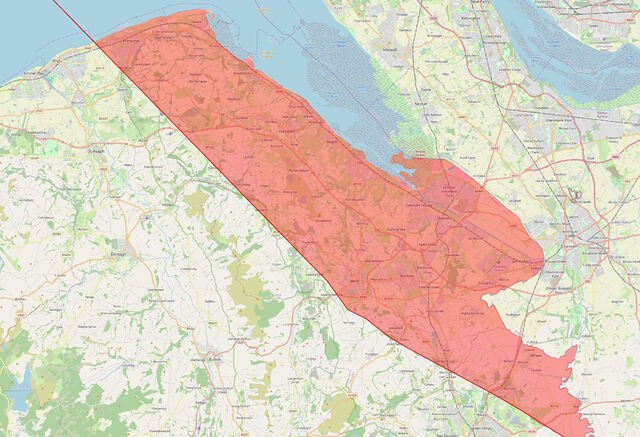

The line crosses the Welsh border at the River Dee, East of Wrexham, leaving a narrow sliver of Wales that’s technically closer to Scotland than it is to Ireland, running up the coastline from Connah’s Quay to Prestatyn and going as far inland as Mold before – as is the case in most of Wales – you’re once again closer to Ireland:

I’d never have guessed that there were any parts of Wales that were closer to Scotland than they were to Ireland, but the map doesn’t lie4

Anyway: that’s how I got distracted, today. And along the way I learned a lot about geodata encoding, a little about Python, and a couple of surprising things about geography5.

Footnotes

1 Not to mention the crazy history of places like Berwick-upon-Tweed, which has jumped the border several times, and Ba Green, ownership of which has traditionally been decided by game of football.

2 Or, at least: it’s the one that’s most-widely used and so I could find lots of helpful StackOverflow answers when I got stuck!

3 Interesting… if you’re specifically looking for some geographical trivia, that is!

4 Okay, the map lies a little. My program was only simple so it plotted everything on a flat plane, failing to accommodate for Earth’s curvature. The difference is probably marginal, but if you happen to live on or very close to the red line, you might need to do your own research!

5 Like: Chester and Rugby are closer to Scotland than they are to Ireland, and Harpenden and Towcester are closer to Ireland than they are to Scotland! Who knew?