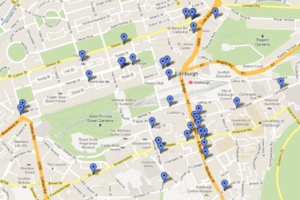

The OpenStreetMap project consists of raw map data, collected and aggregated by thousands of users. This tutorial covers the configuration and maintenance of a web service using Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM), which is based on the OpenStreetMap d

The OpenStreetMap project consists of raw map data, collected and aggregated by thousands of users. However, its open access policy sparked a number of collateral projects, which collectively cover many of the features typically offered by commercial mapping services.

The most obvious advantage in using OpenStreetMap-based software over a commercial solution is economical convenience, because OpenStreetMap comes as free (both as in beer and as in speech) software. The downside is that it takes a little configuration in order to setup a working web service.

This tutorial covers the configuration and maintenance of a web service which can answer questions such as:

- What is the closest street to a given pair of coordinates?

- What’s the best way to get from point A to point B?

- How long does it take to get from point A to point B with a car, or by foot?

The software that makes this possible is an open-source project called Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM), which is based on the OpenStreetMap data. Functionalities to embed OpenStreetMaps in Web pages are already provided out-of-the-box by APIs such as OpenLayers.

…

While slightly dated, I found this guide to be really valuable in my effort to set up a server that could spit out fastest walking routes around Oxford to support a PWA-driven tour of places relevant to J. R. R. Tolkien’s life, at my “day job”.