This is the third in a series of four blog posts about my experience of being called for jury duty in 2013.

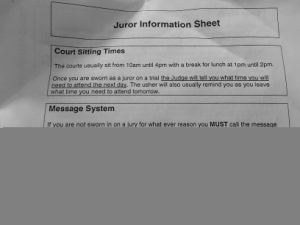

My second day of jury duty was more-successful than the first, in that I was actually assigned to a case, rather than spending the better part of the day sitting around in a waiting room. I knew that this was likely (though not certain, on account of the nature of the randomisation process used, among other things: more on that later) because I’d called the “jury line” the previous night. I suspect this is common, but the other potential jurors and I were given a phone number to call “after around 3:45pm to 4pm” each day, letting us know whether we’d be needed for the following day.

The jury assembly area now only contained the people who’d been brought in, like me, for the upcoming case: a total of 15 of us. I was surprised at quite how many of the other potential jurors showed such negativity about being here: certainly, it’s inconvenient and the sitting-around is more than a little dull if (unlike me) you haven’t brought something to work on or to read, but is it so hard to see the good parts of serving on a jury, too? Personally, I was already glad of the opportunity: okay, the timing wasn’t great… with work commitments keeping me busy, as well as buying a house (more on that later!), working on my course, (finally) getting somewhere with my dad’s estate, and the tail end of a busy release cycle of Three Rings, I already had quite enough going on! But I’ve always been interested in the process of serving on a jury, and besides: I feel that it’s an important civic duty that one really ought to throw oneself at.

If it were a job that you had to volunteer for, rather than being selected at random (and thankfully it isn’t! – can you imagine how awful our justice system would be if it were!), I’d have probably volunteered for it, at some point. Just not, perhaps, now. Ah well.

The jury officer advised us of the expected duration of the trial (up to two days), and made a note of each of our swearing-in choices: each juror could opt to swear an oath on the Bible, Koran, Japji Sahib, Gita, or to make an affirmation (incredibly the Wikipedia page on Jurors’ oaths lacked an entry for the United Kingdom until I added it, just now). In case they were they were empanelled onto a jury, the officer wanted to have the appropriate holy book and/or oath card ready to-hand: courtrooms, it turns out, are reasonably well-stocked with religious literature!

Once assembled, we were filed down to the courtroom, where a further randomisation process took place: a clerk for the court shuffled a deck of cards, and drew 12 at random, one at a time. From each, she read a name – having been referred to it so often lately, I had almost expected to continue to be referred to by my juror number, and had made sure that I knew it by heart – and each person thus chosen made their way to a seat in the jury benches. I was chosen sixth – I was on a jury! The people not chosen were sent back up to the assembly area, so that they could be called down to replace any of us (if our service was successfully challenged – for example, if it turned out that we personally knew the defendant), but were presumably dismissed after it became clear that this was not going to happen.

Then, each of our names were read out again, before each of us were sworn in. This, we were told, was the last chance for any challenge to be raised against us. About half of the jurors opted to affirm (including me: none of those scriptures have any special significance for me; and furthermore I’d like to think that I shouldn’t need to swear that I’m going to do the right thing to begin with); the other half had chosen to swear on the New Testament.

The trial itself went… pretty much like you’ve probably seen it in television dramas: the more-realistic ones, anyway. The prosecution explained the charges and presented evidence and witnesses, which were then cross-examined by the defence (and, ocassionally, re-examined by the prosecution). The defence produced their own evidence and witnesses – including the defendant, vice-versa. The judge interrupted from time to time to question witnesses himself, or to clarify points of law with the counsel or to explain proceedings to the jury.

The trial spilled well into a second day, and I was personally amazed to see quite how much attention to detail was required of the legal advocates. Even evidence that at first seemed completely one-sided could be turned around: for example, some CCTV footage shown by the prosecution was examined by the defence (with the help of a witness) and demonstrated to potentially show something quite different from what first appeared to be the case. The adage that “the camera never lies” has never felt farther from the truth, to me, as the moment that I realised that what I was seeing in a courtroom could be interpreted in two distinctly different ways.

Eventually, we were dismissed to begin our deliberations, under instruction to return a unanimous verdict. I asked if any of the other jurors had done this before, and – when one said that she had – I suggested that she might like to be our chairwoman and forewoman (interestingly, the two don’t have to be the same person – you can have one person chair the deliberations, and another one completely return the verdict to the courtroom – but I imagine that it’s more-common that they are). She responded that no, she wouldn’t, and instead nominated me: I asked if anybody objected, and, when nobody did, accepted the role.

I can’t talk about the trial itself, as you know, but I can say that it took my jury a significant amount of time to come to our decision. A significant part of our trial was hinged upon the subjective interpretation of a key phrase in law. Without giving away the nature of the case, I can find an example elsewhere in law: often, you’ll find legislation that compares illegal acts to what “a reasonable person” would do – you know the kind of things I mean – and its easy to imagine how a carefully-presented case might leave the verdict dependent on the jury’s interpretation of what “reasonable” means. Well: our case didn’t involve the word “reasonable”, but there are plenty of other such words in law that are equally open-to-interpretation, and we had one of these to contend with.

We spent several hours discussing the case, which is an incredibly exhausting experience, but eventually we came to a unanimous decision, and everybody seemed happy with our conclusion. As we left the court later, one of the other jurors told me that if she “was ever on trial, and she hadn’t done it, she’d want us as her jury”. I considered explaining that really, it doesn’t work like that, but I understood the sentiment: we’d all worked hard to come to an agreement of the truth buried in all of the evidence, and I was pleased to have worked alongside them all.

I stood in the courtroom to deliver our verdict, taking care not to make eye contact with the defendant in the dock nor with the group in the corner of the public gallery (whom I suspected to have been the alleged victim and their family). We waited around for the administration that followed, and then were excused.

The whole thing was a tiring but valuable experience. I can’t say it’s over yet; I’m still technically on-call to serve on a second jury, if I’m needed (but I’ve returned to work in the meantime, until I hear otherwise). But if nothing else of interest comes from my jury service, I feel like it’s been worthwhile: I’ve done my but to help ensure that a just and correct decision was made in a case that will have had great personal importance to several individuals and their families. I could have done with a little bit less of sitting around in waiting rooms, but I’ve still been less-unimpressed by the efficiency of the justice system than I was lead to believe that I would be by friends who’ve done jury duty before.