In kind-of local news, I see that the folks at Diamond Light Source (which I got to visit last year) have been helping the Bodleian (who I used to work for) to X-ray one of their Herculaneum scrolls (which I’ve written about before). That’s really cool.

Tag: history

Yr Wyddfa’s First Email

On Wednesday, Vodafone announced that they’d made the first ever satellite video call from a stock mobile phone in an area with no terrestrial signal. They used a mountain in Wales for their experiment.

It reminded me of an experiment of my own, way back in around 1999, which I probably should have made a bigger deal of. I believe that I was the first person to ever send an email from the top of Yr Wyddfa/Snowdon.

Nowadays, that’s an easy thing to do. You pull your phone out and send it. But back then, I needed to use a Psion 5mx palmtop, communicating over an infared link using a custom driver (if you ever wondered why I know my AT-commands by heart… well, this isn’t exactly why, but it’s a better story than the truth) to a Nokia 7110 (fortunately it was cloudy enough to not interfere with the 9,600 baud IrDA connection while I positioned the devices atop the trig point), which engaged a GSM 2G connection, over which I was able to send an email to myself, cc:’d to a few friends.

It’s not an exciting story. It’s not even much of a claim to fame. But there you have it: I was (probably) the first person to send an email from the summit of Yr Wyddfa. (If you beat me to it, let me know!)

Horse-Powered Locomotives

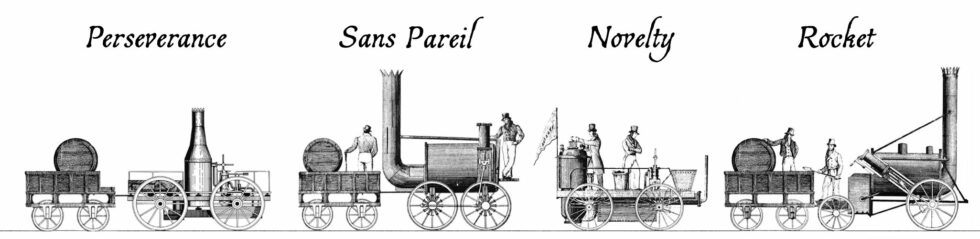

You’re probably familiar with the story of George and Robert Stephenson’s Rocket, a pioneering steam locomotive built in 1829.

If you know anything, it’s that Rocket won a competition and set the stage for a revolution in railways lasting for a century and a half that followed. It’s a cool story, but there’s so much more to it that I only learned this week, including the bonkers story of 19th-century horse-powered locomotives.

The Rainhill Trials

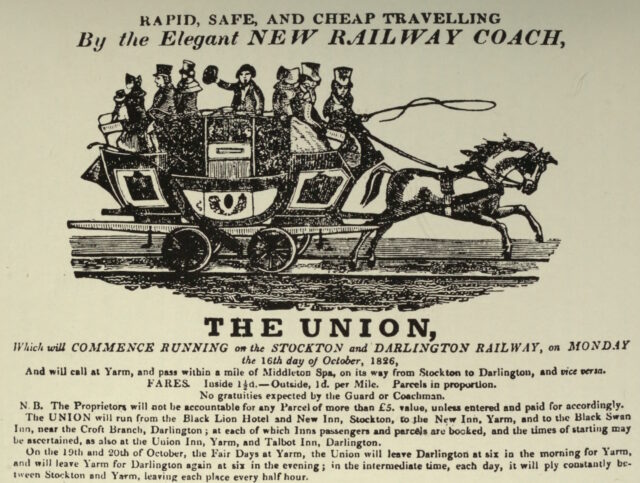

Over the course of the 1820s, the world’s first inter-city railway line – the Liverpool & Manchester Railway – was constructed. It wasn’t initially anticipated that the new railway would use steam locomotives at all: the technology was in its infancy, and the experience of the Stockton & Darlington railway, over on the other side of the Pennines, shows why.

The Stockton & Darlington railway was opened five years before the new Liverpool & Manchester Railway, and pulled its trains using a mixture of steam locomotives and horses1. The early steam locomotives they used turned out to be pretty disastrous. Early ones frequently broke their cast-iron wheels so frequently; some were too heavy for the lines and needed reconstruction to spread their weight; others had their boilers explode (probably after safety valves failed to relieve the steam pressure that builds up after bringing the vehicle to a halt); all got tied-up in arguments about their cost-efficiency relative to horses.

Nearby, at Hetton colliery – the first railway ever to be designed to never require animal power – the Hetton Coal Company had become so-dissatisfied with the reliability and performance of their steam locomotives – especially on the inclines – that they’d had the entire motive system. They’d installed a cable railway – a static steam engine pulled the mine carts up the hill, rather than locomotives.

This kind of thing was happening all over the place, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company were understandably cautious about hitching their wagon to the promise of steam locomotives on their new railway. Furthermore, they were concerned about the negative publicity associated with introducing to populated areas these unpopular smoke-belching engines.

But they were willing to be proven wrong, especially after George Stephenson pointed out that this new, long, railway could find itself completely crippled by a single breakdown were it to adopt a cable system. So: they organised a competition, the Rainhill Trials, to allow locomotive engineers the chance to prove their engines were up to the challenge.

The challenge was this: from a cold start, each locomotive had to haul three times its own weight (including their supply of fuel and water), a mile and three-quarters (the first and last eighth of a mile of which were for acceleration and deceleration, but the rest of which must maintain a speed of at least 10mph), ten times, then stop for a break before doing it all again.

Four steam locomotives took part in the competition that week. Perseverance was damaged in-transit on the way to the competition and was only able to take part on the last day (and then only achieving a top speed of 6mph), but apparently its use of roller bearing axles was pioneering. The very traditionally-designed Sans Pareil was over the competition’s weight limit, burned-inefficiently (thanks perhaps to an overenthusiastic blastpipe that vented unburned coke right out of the funnel!), and broke down when one of its cylinders cracked2. Lightweight Novelty – built in a hurry probably out of a fire engine’s parts – was a crowd favourite with its integrated tender and high top speed, but kept breaking down in ways that could not be repaired on-site. And finally, of course, there was Rocket, which showcased a combination of clever innovations already used in steam engines and locomotives elsewhere to wow the judges and take home the prize.

But there was a fifth competitor in the Rainhill Trials, and it was very different from the other four.

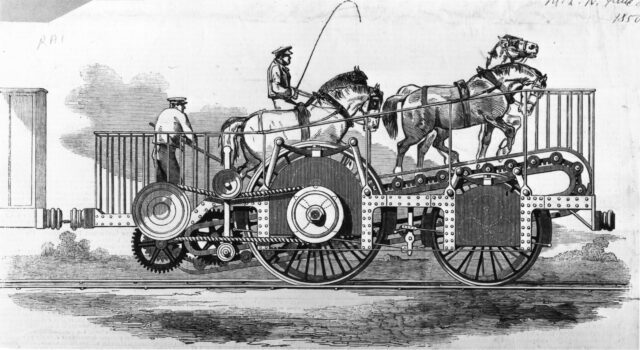

Cycloped

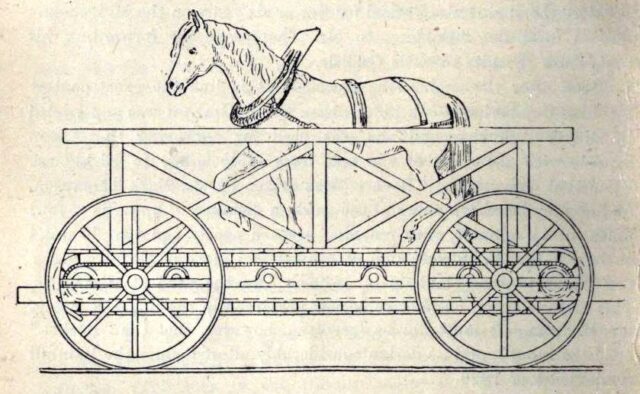

When you hear the words horse-powered locomotive, you probably think of a horse-drawn train. But that’s not a locomotive: a locomotive is a vehicle that, by definition, propels itself3. Which means that a horse-powered locomotive needs to carry the horse that provides its power…

…which is exactly what Cycloped did. A horse runs on a treadmill, which turns the wheels of a vehicle. The vehicle (with the horse on it) move. Tada!4

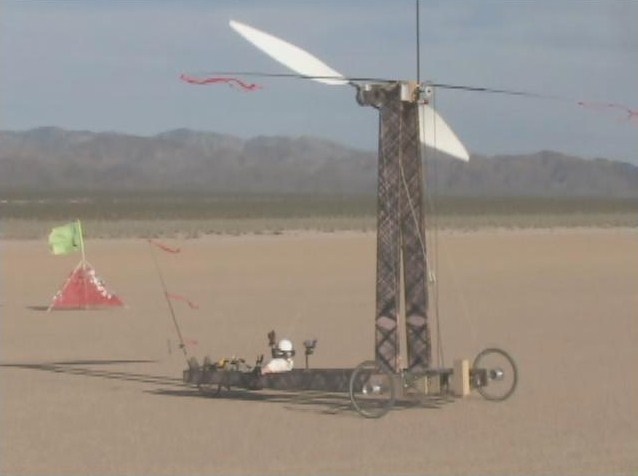

You might look at that design and, not-unreasonably, decide that it must be less-efficient than just having the horse pull the damn vehicle in the first place. But that isn’t necessarily the case. Consider the bicycle which can transport itself and a human both faster and using less-energy than the human would achieve by walking. Or look at wind turbine powered vehicles like Blackbird, which was capable of driving under wind power alone at three times the speed of a tailwind and twice the speed of a headwind. It is mechanically-possible to improve the speed and efficiency of a machine despite adding mass, so long as your force multipliers (e.g. gearing) is done right.

Cycloped didn’t work very well. It was slower than the steam locomotives and at some point the horse fell through the floor of the treadmill. But as I’ve argued above, the principle was sound, and – in this early era of the steam locomotive, with all their faults – a handful of other horse-powered locomotives would be built over the coming decades.

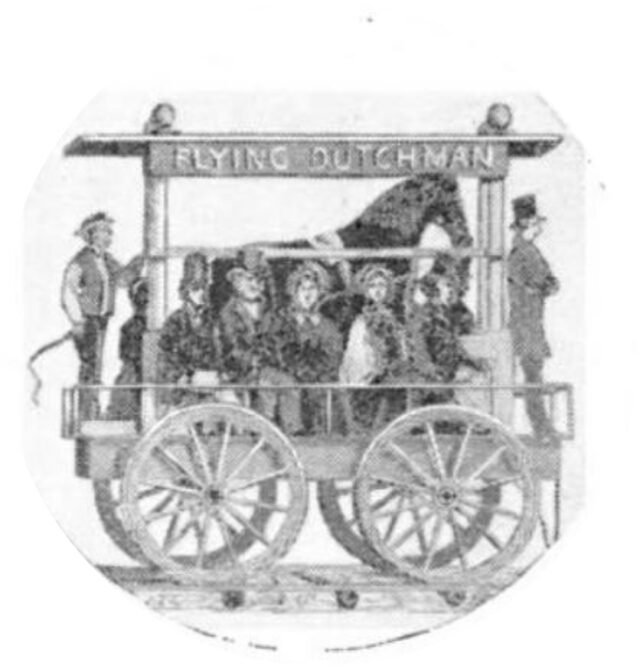

Over in the USA, the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company successfully operated a passenger service using the Flying Dutchman, a horse-powered locomotive with twelve seats for passengers. Capable of travelling at 12mph, this demonstrated efficiency multiplication over having the same horse pull the vehicle (which would either require fewer passengers or a dramatically reduced speed).

As late as the early 1850s, people were still considering this strange approach. The 1851 Great Exhibition at the then brand-new Crystal Palace featured Impulsoria, which represents probably the pinnacle of this particular technological dead-end.

Capable of speeds up to 20mph, it could go toe-to-toe with many contemporary steam locomotives, and it featured a gearbox to allow the speed and even direction of travel to be controlled by the driver without having to adjust the walking speed of the two to four horses that provided the motive force.

Personally, I’d love to have a go on something like the Flying Dutchman: riding a horse-powered vehicle with the horse is just such a crazy idea, and a road-capable variant could make for a much better city tour vehicle than those 10-person bike things, especially if you’re touring a city with a particularly equestrian history.

Footnotes

1 From 1828 the Stockton & Darlington railway used horse power only to pull their empty coal trucks back uphill to the mines, letting gravity do the work of bringing the full carts back down again. But how to get the horses back down again? The solution was the dandy wagon, a special carriage that a horse rides in at the back of a train of coal trucks. It’s worth looking at a picture of one, they’re brilliant!

2 Sans Pareil’s cylinder breakdown was a bit of a spicy issue at the time because its cylinders had been manufactured at the workshop of their rival George Stephenson, and turned out to have defects.

3 You can argue in the comments whether a horse itself is a kind of locomotive. Also – and this is the really important question – whether or not Fred Flintstone’s car, which is propelled by his feed, is a kind locomotive or not.

4 Entering Cycloped into a locomotive competition that expected, but didn’t explicitly state, that entrants had to be a steam-powered locomotive, sounds like exactly the kind of creative circumventing of the rules that we all loved Babe (1995) for. Somebody should make a film about Cycloped.

US Constitution and Presidential Assassinations

Hypothetically-speaking, what would happen if convicted felon Donald Trump were assassinated in-between his election earlier this month and his inauguration in January? There’ve been at least two assassination attempts so far, so it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that somebody will have another go at some point1.

Hello, Secret Service agents! Thanks for visiting my blog. I assume I managed to get the right combination of keywords to hit your watchlist. Just to be clear, this is an entirely hypothetical discussion. I know that you’ve not always been the smartest about telling fiction from reality. But as you’ll see, I’m just using the recent assassination attempts as a framing device to talk about the history of the succession of the position of President-Elect. Please don’t shoot me.

If the US President dies in office – and this happens around 18% of the time2 – the Vice-President becomes President. But right now, convicted felon Donald Trump isn’t President. He’s President-Elect, which is a term used distinctly from President in the US Constitution and other documents.

It turns out that the answer is that the Vice-President-Elect becomes President at the inauguration. This boring answer came to us through three different Constitutional Amendments, each with its own interesting tale.

The Twelfth Amendment (1804) mostly existed to reform the Electoral College. Prior to the adoption of the Twelfth Amendment, the Electoral College members each cast two ballots to vote for the President and Vice-President, but didn’t label which ballot was which position: the runner-up became Vice-President. The electors would carefully and strategically have one of their number cast a vote for a third-party candidate to ensure the person they wanted to be Vice-President didn’t tie with the person they wanted to be President. Around the start of the 19th century this resulted in several occasions on which the President and Vice-President had been bitter rivals but were now forced to work together3.

While fixing that, the Twelfth Amendment also saw fit to specify what would happen if between the election and the inauguration the President-Elect died: that the House of Representatives could choose a replacement one (by two-thirds majority), or else it’d be the Vice-President. Interesting that it wasn’t automatically the Vice-President, though!

The Twentieth Amendment (1933) was written mostly with the intention of reducing the “lame duck” period. Here in the UK, once we elect somebody, they take power pretty-much immediately. But in the US, an election in November traditionally resulted in a new President being inaugurated almost half a year later, in March. So the Twentieth Amendment reduced this by a couple of months to January, which is where it is now.

In an era of high-speed road, rail, and air travel and digital telecommunications even waiting from November to January seems a little silly, though. In any case, a secondary feature of the Twentieth Amendment was that it removed the rule about the House of Representatives getting to try to pick a replacement President first, saying that they’d just fall-back on the Vice-President in the first instance. Sorted.

Just 23 days later, the new rule almost needed to be used, except that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s would-be assassin Giuseppe Zangara missed his tricky shot.

The Twentieth Amendment (1967) aimed to fix rules-lawyering. The constitution originally said that f the President is removed from office, dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to use his powers and fulfil his duties, then those powers and duties go to the Vice-President.

Note the wording there. The constitution said that if a President died, their their duties and powers would go to the Vice-President. Not the Presidency itself. You’d have a Vice-President, acting as President, who wasn’t actually a President. And that might not matter 99% of the time… but it’s the edge cases that get you.[foonote]Looking for some rules-lawyering? Okay: what about rules on Presidential term limits? You can’t have more than two terms as President, but what if you’ve had a term as Vice-President but acting with Presidential powers after the President died? Can you still have two terms? This is the kind of constitutional craziness that munchkin US history scholars get off on.[/footnote]

It also insisted that if there’s no Vice-President, you’ve got to get one. You’d think it was obvious that if the office of Vice-President exists in part to provide a “backup” President in case, y’know, the nearly one-in-five chance that the President dies… that a Vice-President who finds themselves suddenly the President would probably want to have one!

But no: 18 Presidents4 served without a Vice-President for at least some of their term: four of them never had a Vice-President. That includes 17th President Andrew Johnson, who you’d think would have known better. Johnson was Vice-President under Abraham Lincoln until, only a month after the inauguration, Lincoln was assassinated, putting Johnson in change of the country. And he never had a Vice-President of his own. He served only barely shy of the full four years without one.

Anyway; that was a long meander through the history of the Constitution of a country I don’t even live in, to circle around a question that doesn’t matter. The thought randomly came to me while I was waiting for the traffic lights at the roadworks outside my house to change. And now I know the answer.

Very hypothetically, of course.

Footnotes

1 My personal headcanon is that the would-be assassins are time travellers from the future, Chrononauts-style, trying to flip a linchpin and bring about a stable future in which he wasn’t elected. I don’t know whether or not that makes Elon Musk one of the competing time travellers, but you could conceivably believe that he’s Squa Tront in disguise, couldn’t you?

2 The US has had 45 presidents, of whom eight have died during their time in office. Of those eight, four – half! – were assassinated! It’s a weird job. 8 ÷ 45 ≈ 18%.

3 If you’re familiar with Hamilton, you’ll recall its characterisation of the election of 1800 with President Thomas Jefferson dismissing his Vice-President Aaron Burr after a close competition for the seat of President which was eventually settled when Alexander Hamilton instructed Federalist party members in the House of Representatives to back Jefferson over Burr. The election result really did happen like that – it seems that whichever Federalist in the Electoral College that was supposed to throw away their second vote failed to do so! – but it’s not true that he was kicked-out by Jefferson: in fact, he served his full four years as Vice-President, although Jefferson tried to keep him as far from actual power as possible and didn’t nominate him as his running-mate in 1804. Oh, and in 1807 Jefferson had Burr arrested for treason, claiming that Burr was trying to capture part of the South-West of North America and force it to secede and form his own country: the accusation didn’t stick, but it ruined Burr’s already-faltering political career. Anyway, that’s a diversion.

4 17 different people, but that’s not how we could Presidents apparently.

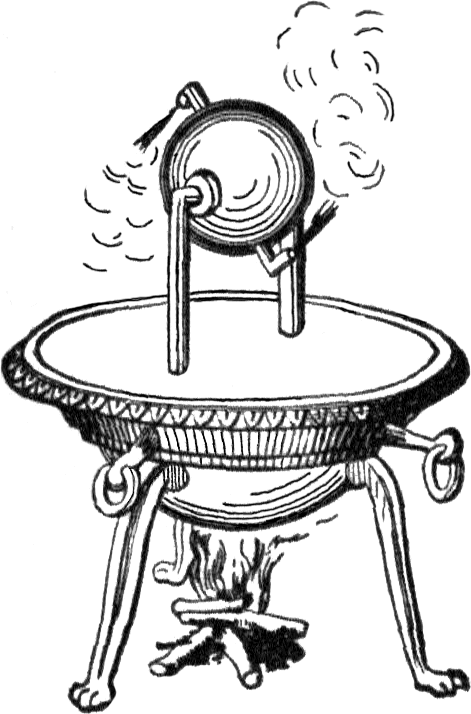

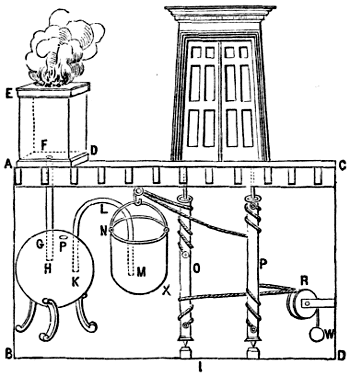

Hero of Alexandria

A little under two millennia ago1 there lived in the Egyptian city of Alexandria a Greek mathematician and inventor named Hero2, and he was a total badass who invented things that you probably thought came way later, and come up with mathematical tricks that we still use to this day3.

Inventions

- automatic doors (powered either by pressure plates or by lit fires),

- vending machines, which used the weight of a dispensed coin to open a valve and dispense holy water,

- windmills (by which I mean wind-powered stationary machines capable of performing useful work),

- the force pump – this is the kind of mechanism found in traditional freestanding village water pumps – for use in a fire engine,

- float-valve and water-pressure based equilibrium pumps, like those found in many toilet cisterns, and

- a programmable robot: this one’s a personal favourite of mine because it’s particularly unexpected – Hero’s cart was a three-wheeled contraption whose wheels were turned by a falling weight pulling on a rope, but the rope could be knotted and looped back over itself (here’s a modern reimplementation using Lego) to form a programmed path for the cart

Mathematics

If you know of Hero because of his mathematical work, it’s probably thanks to his pre-trigonometric work on calculating the area of a triangle based only on the lengths of its sides.

But I’ve always been more-impressed by the iterative5 mechanism he come up with by which to derive square roots. Here’s how it works:

- Let n be the number for which you want to determine the square root.

- Let g1 be a guess as to the square root. You can pick any number; it can be 1.

- Derive a better guess g2 using g2 = ( g1 + n / g1 ) / 2.

- Repeat until gN ≈ gN-1, for a level of precision acceptable to you. The algorithm will be accurate to within S significant figures if the derivation of each guess is rounded to S + 1 significant figures.

That’s a bit of a dry way to tell you about it, though. Wouldn’t it be better if I showed you?

Put any number from 1 to 999 into the box below and see a series of gradually-improving guesses as to its square root6.

Interactive Widget

(There should be an interactive widget here. Maybe you’ve got Javascript disabled, or maybe you’re reading this post in your RSS reader?)

Maths is just one of the reasons Hero is my hero. And now perhaps he can be your hero too.

Footnotes

1 We’re not certain when he was born or died, but he wrote about witnessing a solar eclipse that we know to have occurred in 62 CE, which narrows it down a lot.

2 Or Heron. It’s not entirely certain how his name was pronounced, but I think “Hero” sounds cooler so I’m going with that.

3 Why am I blogging about this? Well: it turns out that every time I speak on some eccentric subject, like my favourite magic trick, I come off stage with like three other ideas for presentations, which leads to an exponential growth about “things I’d like to talk about”. Indeed, my OGN talk on the history of Oxford’s telephone area code was one of three options I offered to the crowd to vote on at the end of my previous OGN talk! In any case, I’ve decided that the only way I can get all of this superfluity of ideas out of my head might be to blog about them, instead; so here’s such a post!

4 If the diagram’s not clear, here’s the essence of the aeolipile: it’s a basic steam reaction-engine, in which steam forces its way out of a container in two different directions, causing the container to spin on its axis like a catherine wheel.

5 You can also conceive of it as a recursive algorithm if that’s your poison, for example if you’re one of those functional purists who always seem somehow happier about their lives than I am with mine. What’s that about, anyway? I tried to teach myself functional programming in the hope of reaching their Zen-like level of peace and contentment, but while I got reasonably good at the paradigm, I didn’t find enlightenment. Nowadays I’m of the opinion that it’s not that functional programming leads to self-actualisation so much as people capable of finding a level of joy in simplicity are drawn to functional programming. Or something. Anyway: what was I talking about? Oh, yeah: Hero of Alexandria’s derivation of square roots.

6 Why yes, of course I open-sourced this code.

Bletchley Park

The eldest is really getting into her WW2 studies at school, so I arranged a trip for her and a trip to the ever-excellent Bletchley Park for a glimpse at the code war that went on behind the scenes. They’re clearly looking forward to the opportunity to look like complete swots on Monday.

Bonus: I got to teach them some stories about some of my favourite cryptanalysts. (Max props to the undersung Mavis Batey!)

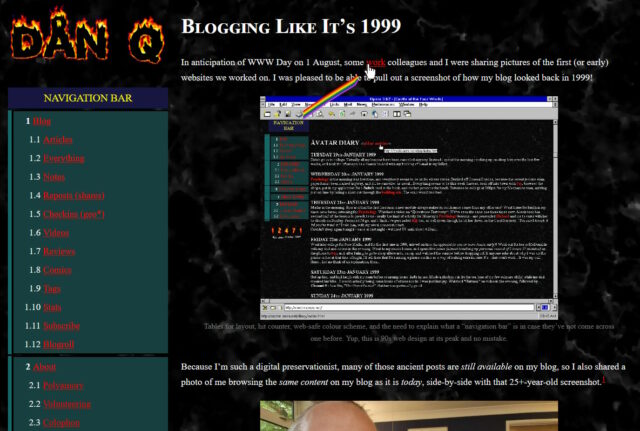

Even More 1999!

Spencer’s filter

Last month I implemented an alternative mode to view this website “like it’s 1999”, complete with with cursor trails, 88×31 buttons, tables for layout1, tiled backgrounds, and even a (fake) hit counter.

One thing I’d have liked to do for 1999 Mode but didn’t get around to would have been to make the images look like it was the 90s, too.

Back then, many Web users only had graphics hardware capable of displaying 256 distinct colours. Across different platforms and operating systems, they weren’t even necessarily the same 256 colours2! But the early Web agreed on a 216-colour palette that all those 8-bit systems could at least approximate pretty well.

I had an idea that I could make my images look “216-colour”-ish by using CSS to apply an SVG filter, but didn’t implement it.

But Spencer, a long-running source of excellent blog comments, stepped up and wrote an SVG filter for me! I’ve tweaked 1999 Mode already to use it… and I’ve just got to say it’s excellent: huge thanks, Spencer!

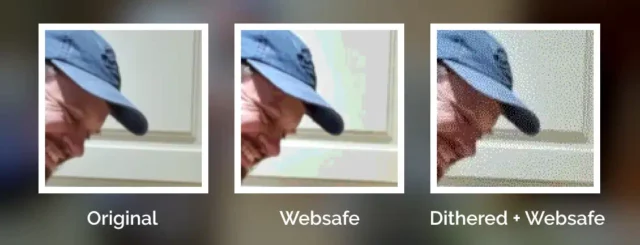

The filter coerces colours to their nearest colour in the “Web safe” palette, resulting in things like this:

Plenty of pictures genuinely looked like that on the Web of the 1990s, especially if you happened to be using a computer only capable of 8-bit colour to view a page built by somebody who hadn’t realised that not everybody would experience 24-bit colour like they did3.

Dithering

But not all images in the “Web safe” palette looked like this, because savvy web developers knew to dither their images when converting them to a limited palette. Let’s have another go:

Dithering introduces random noise to media4 in order to reduce the likelihood that a “block” will all be rounded to the same value. Instead; in our picture, a block of what would otherwise be the same colour ends up being rounded to maybe half a dozen different colours, clustered together such that the ratio in a given part of the picture is, on average, a better approximation of the correct colour.

The result is analogous to how halftone printing – the aesthetic of old comics and newspapers, with different-sized dots made from few colours of ink – produces the illusion of a continuous gradient of colour so long as you look at it from far-enough away.

The other year I read a spectacular article by Surma that explained in a very-approachable way how and why different dithering algorithms produce the results they do. If you’ve any interest whatsoever in a deep dive or just want to know what blue noise is and why you should care, I’d highly recommend it.

You used to see digital dithering everywhere, but nowadays it’s so rare that it leaps out as a revolutionary aesthetic when, for example, it gets used in a video game.

All of which is to say that: I really appreciate Spencer’s work to make my “1999 Mode” impose a 216-colour palette on images. But while it’s closer to the truth, it still doesn’t quite reflect what my website would’ve looked like in the 1990s because I made extensive use of dithering when I saved my images in Web safe palettes5.

Why did I take the time to dither my images, back in the day? Because doing the hard work once, as a creator of graphical Web pages, saves time and computation (and can look better!), compared to making every single Web visitor’s browser do it every single time.

Which, now I think about it, is a lesson that’s still true today (I’m talking to you, developers who send a tonne of JavaScript and ask my browser to generate the HTML for you rather than just sending me the HTML in the first place!).

Footnotes

1 Actually, my “1999 mode” doesn’t use tables for layout; it pretty much only applies a CSS overlay, but it’s deliberately designed to look a lot like my blog did in 1999, which did use tables for layout. For those too young to remember: back before CSS gave us the ability to lay out content in diverse ways, it was commonplace to use a table – often with the borders and cell-padding reduced to zero – to achieve things that today would be simple, like putting a menu down the edge of a page or an image alongside some text content. Using tables for non-tabular data causes problems, though: not only is it hard to make a usable responsive website with them, it also reduces the control you have over the order of the content, which upsets some kinds of accessibility technologies. Oh, and it’s semantically-invalid, of course, to describe something as a table if it’s not.

2 Perhaps as few as 22 colours were defined the same across all widespread colour-capable Web systems. At first that sounds bad. Then you remember that 4-bit (16 colour) palettes used to look look perfectly fine in 90s videogames. But then you realise that the specific 22 “very safe” colours are pretty shit and useless for rendering anything that isn’t composed of black, white, bright red, and maybe one of a few greeny-yellows. Ugh. For your amusement, here’s a copy of the image rendered using only the “very safe” 22 colours.

3 Spencer’s SVG filter does pretty-much the same thing as a computer might if asked to render a 24-bit colour image using only 8-bit colour. Simply “rounding” each pixel’s colour to the nearest available colour is a fast operation, even on older hardware and with larger images.

4 Note that I didn’t say “images”: dithering is also used to produce the same “more natural” feel for audio, too, when reducing its bitrate (i.e. reducing the number of finite states into which the waveform can be quantised for digitisation), for example.

5 I’m aware that my footnotes are capable of nerdsniping Spencer, so by writing this there’s a risk that he’ll, y’know, find a way to express a dithering algorithm as an SVG filter too. Which I suspect isn’t possible, but who knows! 😅

The Eyebrow Painter

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

There are a whole bunch of things that could be the source for the name, e.g. where we found most of their work (The Dipylon Master) or the potter with whom they worked (the Amasis Painter), a favourite theme (The Athena Painter), the Museum that ended up with the most famous thing they did (The Berlin Painter) or a notable aspect of their style. Like, say, The Eyebrow Painter.

Just excellent.

A frowning fish, painted onto a plate, surely makes for the best funerary offering.

If you’ve ever found yourself missing the “good old days” of the web, what is it that you miss?

This is a reply to a post published elsewhere. Its content might be duplicated as a traditional comment at the original source.

This. You wanted to identify a song? Type some of the lyrics into a search engine and hope that somebody transcribed the same lyrics onto their fansite. You needed to know a fact? Better hope some guru had taken the time to share it, or it’d be time for a trip to the library

Not having information instantly easy to find meant that you really treasured your online discoveries. You’d bookmark the best sites on whatever topics you cared about and feel no awkwardness about emailing a fellow netizen (or signing their guestbook to tell them) about a resource they might like. And then you’d check back, manually, from time to time to see what was new.

The young Web was still magical and powerful, but the effort to payoff ratio was harder, and that made you appreciate your own and other people’s efforts more.

Roman object that baffled experts to go on show at Lincoln Museum

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

A mysterious Roman artefact found during an amateur archaeological dig is going on public display in Lincolnshire for the first time.

The object is one of only 33 dodecahedrons found in Britain, and the first to have been discovered in the Midlands.

…

I learned about these… things… from this BBC News story and I’m just gobsmacked. Seriously: what is this thing?

This isn’t a unique example. 33 have been found in Britain, but these strange Roman artefacts turn up all over Europe: we’ve found hundreds of them.

It doesn’t look like they were something that you’d find in any Roman-era household, but they seem to be common enough that if you wandered around third century Northern Europe with one for a week or so you’d surely be able to find somebody who could explain them to you. And yet we don’t know why.

We have absolutely no idea why the Romans made these things. They’re finely and carefully created from bronze, and we find them buried in coin stashes, which suggests that they were valuable and important. But for what? Frustrated archaeologists have come up with all kinds of terrible ideas:

- Maybe they were a weapon, like the ball of a mace or something to be flung from a sling? Nope; they’re not really heavy enough.

- At least one was discovered near a bone staff, so it might have been a decorative scepter? But that doesn’t really go any distance to explaining the unusual shape, even if true (nor does it rule out the possibility of it being some kind of handled tool).

- Perhaps they were a rangefinding tool, where a pair of opposing holes line up only when you’re a particular distance from the tool? If a target of a known size fills the opposite hole in your vision, its distance must be a specific multiple of your distance to the tool. But that seems unlikely because we’ve never found any markings on these that would show which side you were using; also the devices aren’t consistently-sized.

- Roleplayers might notice the similarity to polyhedral dice: maybe they were a game? But the differing-sized holes make them pretty crap dice (researchers have tried), and Romans seemed to favour cubic dice anyway. They’re somewhat too intricate and complex to be good candidates for children’s toys.

- They could be some kind of magical or divination tool, which would apparently fit with the kinds of fortune-telling mysticism believed to be common to the cultures at the sites where they’re found. Do the sides and holes correspond to the zodiac or have some other astrological significance?

- Perhaps it was entirely decorative? Gold beads of a surprisingly-similar design have been found as far away as Cambodia, well outside the reach of the Roman Empire, which might suggest a continuing tradition of an earlier precursor dodecahedron!

- This author thinks they might have acted as a kind of calendar, used for measuring the height of the midday sun by observing way its beam is cast through a pair of holes when the tool is placed on a surface and used to determine when winter grains should be planted.

- Using replicas, some folks online have demonstrated how they could have been used as a knitting tool for making the fingers of gloves using a technique called “spool knitting”. But this knitting technique isn’t believed to have been invented until a millennium later than the youngest of these devices.

- Others have proposed that they were a proof of qualification: something a master metalsmith would construct in order to show that they were capable of casting a complex and intricate object.

I love a good archaeological mystery. We might never know why the Romans made these things, but reading clever people’s speculations about them is great.

Window Tax

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

…in England and Wales

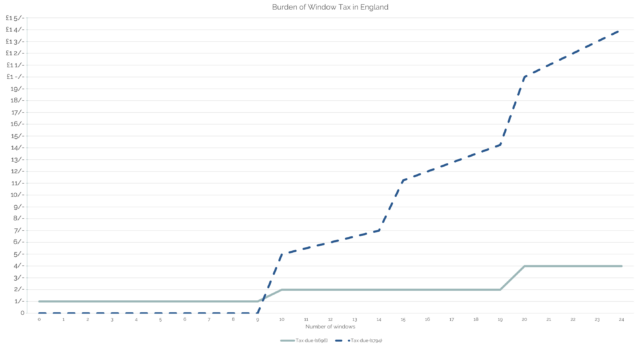

From 1696 until 1851 a “window tax” was imposed in England and Wales1. Sort-of a precursor to property taxes like council tax today, it used an estimate of the value of a property as an indicator of the wealth of its occupants: counting the number of windows provided the mechanism for assessment.

(A particular problem with window tax as enacted is that its “stepping”, which was designed to weigh particularly heavily on the rich with their large houses, was that it similarly weighed heavily on large multi-tenant buildings, whose landlord would pass on those disproportionate costs to their tenants!)

Why a window tax? There’s two ways to answer that:

- A window tax – and a hearth tax, for that matter – can be assessed without the necessity of the taxpayer to disclose their income. Income tax, nowadays the most-significant form of taxation in the UK, was long considered to be too much of an invasion upon personal privacy3.

- But compared to a hearth tax, it can be validated from outside the property. Counting people in a property in an era before solid recordkeeping is hard. Counting hearths is easier… so long as you can get inside the property. Counting windows is easier still and can be done completely from the outside!

…in the Netherlands

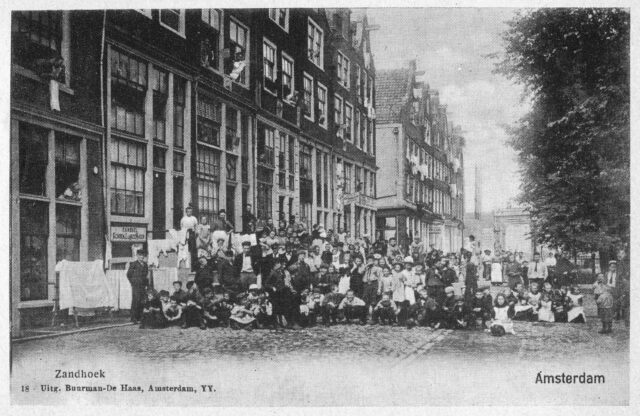

I recently got back from a trip to Amsterdam to meet my new work team and get to know them better.

One of the things I learned while on this trip was that the Netherlands, too, had a window tax for a time. But there’s an interesting difference.

The Dutch window tax was introduced during the French occupation, under Napoleon, in 1810 – already much later than its equivalent in England – and continued even after he was ousted and well into the late 19th century. And that leads to a really interesting social side-effect.

Glass manufacturing technique evolved rapidly during the 19th century. At the start of the century, when England’s window tax law was in full swing, glass panes were typically made using the crown glass process: a bauble of glass would be spun until centrifugal force stretched it out into a wide disk, getting thinner towards its edge.

The very edge pieces of crown glass were cut into triangles for use in leaded glass, with any useless offcuts recycled; the next-innermost pieces were the thinnest and clearest, and fetched the highest price for use as windows. By the time you reached the centre you had a thick, often-swirly piece of glass that couldn’t be sold for a high price: you still sometimes find this kind among the leaded glass in particularly old pub windows5.

As the 19th century wore on, cylinder glass became the norm. This is produced by making an iron cylinder as a mould, blowing glass into it, and then carefully un-rolling the cylinder while the glass is still viscous to form a reasonably-even and flat sheet. Compared to spun glass, this approach makes it possible to make larger window panes. Also: it scales more-easily to industrialisation, reducing the cost of glass.

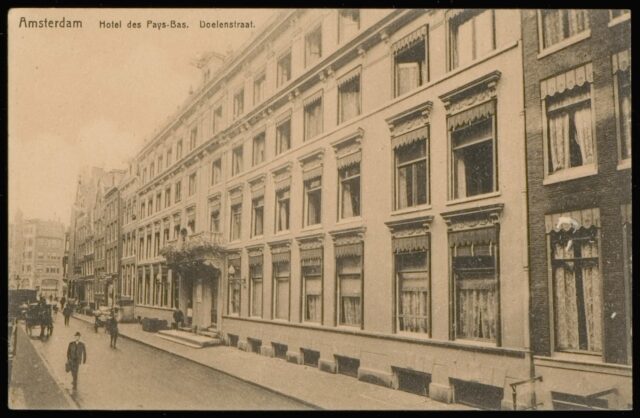

The Dutch window tax survived into the era of large plate glass, and this lead to an interesting phenomenon: rather than have lots of windows, which would be expensive, late-19th century buildings were constructed with windows that were as large as possible to maximise the ratio of the amount of light they let in to the amount of tax for which they were liable6.

That’s an architectural trend you can still see in Amsterdam (and elsewhere in Holland) today. Even where buildings are renovated or newly-constructed, they tend – or are required by preservation orders – to mirror the buildings they neighbour, which influences architectural decisions.

It’s really interesting to see the different architectural choices produced in two different cities as a side-effect of fundamentally the same economic choice, resulting from slightly different starting conditions in each (a half-century gap and a land shortage in one). While Britain got fewer windows, the Netherlands got bigger windows, and you can still see the effects today.

…and social status

But there’s another interesting this about this relatively-recent window tax, and that’s about how people broadcast their social status.

In some of the traditionally-wealthiest parts of Amsterdam, you’ll find houses with more windows than you’d expect. In the photo above, notice:

- How the window density of the central white building is about twice that of the similar-width building on the left,

- That a mostly-decorative window has been installed above the front door, adorned with a decorative leaded glass pattern, and

- At the bottom of the building, below the front door (up the stairs), that a full set of windows has been provided even for the below-ground servants quarters!

When it was first constructed, this building may have been considered especially ostentatious. Its original owners deliberately requested that it be built in a way that would attract a higher tax bill than would generally have been considered necessary in the city, at the time. The house stood out as a status symbol, like shiny jewellery, fashionable clothes, or a classy car might today.

Can we bring back 19th-century Dutch social status telegraphing, please?9

Footnotes

1 Following the Treaty of Union the window tax was also applied in Scotland, but Scotland’s a whole other legal beast that I’m going to quietly ignore for now because it doesn’t really have any bearing on this story.

2 The second-hardest thing about retrospectively graphing the cost of window tax is finding a reliable source for the rates. I used an archived copy of a guru site about Wolverhampton history.

3 Even relatively-recently, the argument that income tax might be repealed as incompatible with British values shows up in political debate. Towards the end of the 19th century, Prime Ministers Disraeli and Gladstone could be relied upon to agree with one another on almost nothing, but both men spoke at length about their desire to abolish income tax, even setting out plans to phase it out… before having to cancel those plans when some financial emergency showed up. Turns out it’s hard to get rid of.

4 There are, of course, other potential reasons for bricked-up windows – even aesthetic ones – but a bit of a giveaway is if the bricking-up reduces the number of original windows to 6, 9, 14 or 19, which are thesholds at which the savings gained by bricking-up are the greatest.

5 You’ve probably heard about how glass remains partially-liquid forever and how this explains why old windows are often thicker at the bottom. You’ve probably also already had it explained to you that this is complete bullshit. I only mention it here to preempt any discussion in the comments.

6 This is even more-pronounced in cities like Amsterdam where a width/frontage tax forced buildings to be as tall and narrow and as close to their neighbours as possible, further limiting opportunities for access to natural light.

7 Yet I’m willing to learn a surprising amount about Dutch tax law of the 19th century. Go figure.

8 Obligatory Pet Shop Boys video link. Can that be a thing please?

9 But definitely not 17th-century Dutch social status telegraphing, please. That shit was bonkers.

Netscape’s Untold Webstories

I mentioned yesterday that during Bloganuary I’d put non-Bloganuary-prompt post ideas onto the backburner, and considered extending my daily streak by posting them in February. Here’s part of my attempt to do that:

Let’s take a trip into the Web of yesteryear, with thanks to our friends at the Internet Archive’s WayBack Machine.

The page we’re interested in used to live at http://www.netscape.com/comprod/columns/webstories/index.html, and promised to be a showcase for best practice in Web

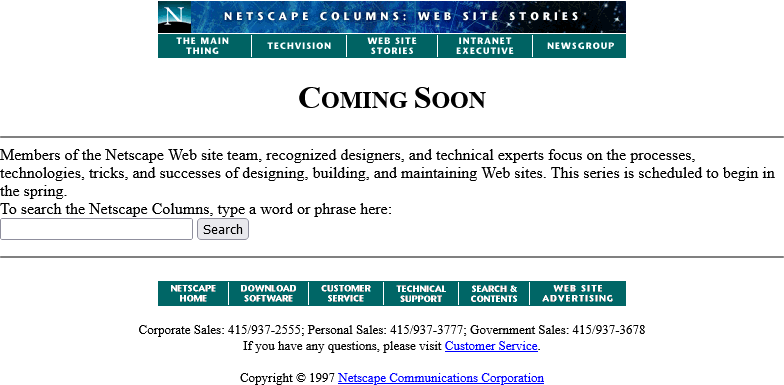

development. Back in October 1996, it looked like this:

The page is a placeholder for Netscape Webstories (or Web Site Stories, in some places). It’s part of a digital magazine called Netscape Columns which published pieces written by Marc Andreeson, Jim Barksdale, and other bigwigs in the hugely-influential pre-AOL-acquisition Netscape Communications.

This new series would showcase best practice in designing and building Web sites1, giving a voice to the technical folks best-placed to speak on that topic. That sounds cool!

Those white boxes above and below the paragraph of text aren’t missing images, by the way: they’re horizontal rules, using the little-known size attribute to specify a

thickness of <hr size=4>!2

Certainly you’re excited by this new column and you’ll come back in November 1996, right?

Oh. The launch has been delayed, I guess. Now it’s coming in January.

The <hr>s look better now their size has been reduced, though, so clearly somebody’s paying attention to the page. But let’s take a moment and look at that page

title. If you grew up writing web pages in the modern web, you might anticipate that it’s coded something like this:

<h2 style="font-variant: small-caps; text-align: center;">Coming Soon</h2>

There’s plenty of other ways to get that same effect. Perhaps you prefer font-feature-settings: 'smcp' in your chosen font; that’s perfectly valid. Maybe you’d use

margin: 0 auto or something to centre it: I won’t judge.

But no, that’s not how this works. The actual code for that page title is:

<center> <h2> <font size="+3">C</font>OMING <font size="+3">S</font>OON </h2> </center>

Back when this page was authored, we didn’t have CSS3. The only styling elements were woven right in amongst the semantic elements of a page4. It was simple to understand and easy to learn… but it was a total mess5.

Anyway, let’s come back in January 1997 and see what this feature looks like when it’s up-and-running.

Nope, now it’s pushed back to “the spring”.

Under Construction pages were all the rage back in the nineties. Everybody had one (or several), usually adorned with one or more of about a thousand different animated GIFs for that purpose.6

Building “in public” was an act of commitment, a statement of intent, and an act of acceptance of the incompleteness of a digital garden. They’re sort-of coming back into fashion in the interpersonal Web, with the “garden and stream” metaphor7 taking root. This isn’t anything new, of course – Mark Bernstein touched on the concepts in 1998 – but it’s not something that I can ever see returning to the “serious” modern corporate Web: but if you’ve seen a genuine, non-ironic “under construction” page published to a non-root page of a company’s website within the last decade, please let me know!

RSS doesn’t exist yet (although here’s a fun fact: the very first version of RSS came out of Netscape!). We’re just going to have to bookmark the page and check back later in the year, I guess…

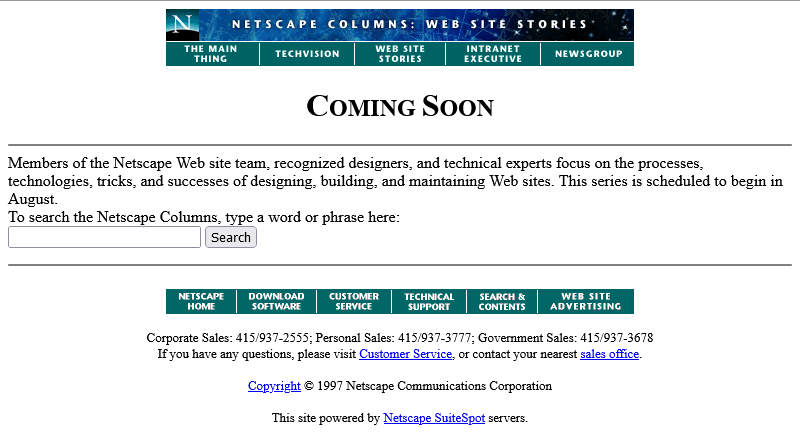

Okay, so February clearly isn’t Spring, but they’ve updated the page… to add a search form.

It’s a genuine <form> tag, too, not one of those old-fashioned <isindex> tags you’d still sometimes find even as late as 1997. Interestingly, it specifies

enctype="application/x-www-form-urlencoded". Today’s developers probably don’t think about the enctype attribute except when they’re doing a form that handles

file uploads and they know they need to switch it to enctype="multipart/form-data", (or their framework does this automatically for them!).

But these aren’t the only options, and some older browsers at this time still defaulted to enctype="text/plain". So long as you’re using a POST

and not GET method, the distinction is mostly academic, but if your backend CGI program anticipates that special

characters will come-in encoded, back then you’d be wise to specify that you wanted URL-encoding or you might get a nasty surprise when somebody turns up using LMB or something

equally-exotic.

Anyway, let’s come back in June. The content must surely be up by now:

Oh come on! Now we’re waiting until August?

At least the page isn’t abandoned. Somebody’s coming back and editing it from time to time to let us know about the still-ongoing series of delays. And that’s not a trivial task: this

isn’t a CMS. They’re probably editing the .html file itself in their favourite text editor, then putting the

appropriate file:// address into their copy of Netscape Navigator (and maybe other browsers) to test it, then uploading the file – probably using FTP – to the webserver… all the while thanking their lucky stars that they’ve only got the one page they need to change.

We didn’t have scripting languages like PHP yet, you see8. We didn’t really have static site generators. Most servers didn’t implement server-side includes. So if you had to make a change to every page on a site, for example editing the main navigation menu, you’d probably have to open and edit dozens or even hundreds of pages. Little wonder that framesets caught on, despite their (many) faults, with their ability to render your navigation separately from your page content.

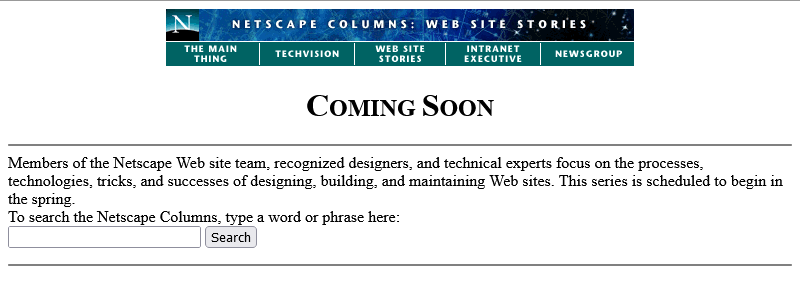

Okay, let’s come back in August I guess:

Now we’re told that we’re to come back… in the Spring again? That could mean Spring 1998, I suppose… or it could just be that somebody accidentally re-uploaded an old copy of the page.

Hey: the footer’s gone too? This is clearly a partial re-upload: somebody realised they were accidentally overwriting the page with the previous-but-one version, hit “cancel” in their FTP client (or yanked the cable out of the wall), and assumed that they’d successfully stopped the upload before any damage was done.

They had not.

I didn’t mention that top menu, did I? It looks like it’s a series of links, styled to look like flat buttons, right? But you know that’s not possible because you can’t rely on

having the right fonts available: plus you’d have to do some <table> trickery to lay it out, at which point you’d struggle to ensure that the menu was the same width

as the banner above it. So how did they do it?

The menu is what’s known as a client-side imagemap. Here’s what the code looks like:

<a href="/comprod/columns/images/nav.map"> <img src="/comprod/columns/images/websitestories_ban.gif" width=468 height=32 border=0 usemap="#maintopmap" ismap> </a><map name="mainmap"> <area coords="0,1,92,24" href="/comprod/columns/mainthing/index.html"> <area coords="94,1,187,24" href="/comprod/columns/techvision/index.html"> <area coords="189,1,278,24" href="/comprod/columns/webstories/index.html"> <area coords="280,1,373,24" href="/comprod/columns/intranet/index.html"> <area coords="375,1,467,24" href="/comprod/columns/newsgroup/index.html"> </map>

The image (which specifies border=0 because back then the default behaviour for graphical browser was to put a thick border around images within hyperlinks) says

usemap="#maintopmap" to cross-reference the <map> below it, which defines rectangular areas on the image and where they link to, if you click them! This

ingenious and popular approach meant that you could transmit a single image – saving on HTTP round-trips, which were

relatively time-consuming before widespread adoption of HTTP/1.1‘s persistent connections –

along with a little metadata to indicate which pixels linked to which pages.

The ismap attribute is provided as a fallback for browsers that didn’t yet support client-side image maps but did support server-side image maps: there were a few!

When you put ismap on an image within a hyperlink, then when the image is clicked on the href has appended to it a query parameter of the form

?123,456, where those digits refer to the horizontal and vertical coordinates, from the top-left, of the pixel that was clicked on! These could then be decoded by the

webserver via a .map file or handled by a CGI

program. Server-side image maps were sometimes used where client-side maps were undesirable, e.g. when you want to record the actual coordinates picked in a spot-the-ball competition or

where you don’t want to reveal in advance which hotspot leads to what destination, but mostly they were just used as a fallback.9

Both client-side and server-side image maps still function in every modern web browser, but I’ve not seen them used in the wild for a long time, not least because they’re hard (maybe impossible?) to make accessible and they can’t cope with images being resized, but also because nowadays if you really wanted to make an navigation “image” you’d probably cut it into a series of smaller images and make each its own link.

Anyway, let’s come back in October 1997 and see if they’ve fixed their now-incomplete page:

Oh, they have! From the look of things, they’ve re-written the page from scratch, replacing the version that got scrambled by that other employee. They’ve swapped out the banner and menu for a new design, replaced the footer, and now the content’s laid out in a pair of columns.

There’s still no reliable CSS, so you’re not looking at columns: (no implementations until 2014) nor at

display: flex (2010) here. What you’re looking at is… a fixed-width <table> with a single row and three columns! Yes: three – the middle column

is only 10 pixels wide and provides the “gap” between the two columns of text.10

This wasn’t Netscape’s only option, though. Did you ever hear of the <multicol> tag? It was the closest thing the early Web had to a semantically-sound,

progressively-enhanced multi-column layout! The author of this page could have written this:

<multicol cols=2 gutter=10 width=301>

<p>

Want to create the best possible web site? Join us as we explore the newest

technologies, discover the coolest tricks, and learn the best secrets for

designing, building, and maintaining successful web sites.

</p>

<p>

Members of the Netscape web site team, recognized designers, and technical

experts will share their insights and experiences in Web Site Stories.

</p>

</multicol>

That would have given them the exact same effect, but with less code and it would have degraded gracefully. Browsers ignore tags they don’t understand, so a browser without

support for <multicol> would have simply rendered the two paragraphs one after the other. Genius!

So why didn’t they? Probably because <multicol> only ever worked in Netscape Navigator.

Introduced in 1996 for version 3.0, this feature was absolutely characteristic of the First Browser War. The two “superpowers”, Netscape and Microsoft, both engaged in unilateral changes to the HTML specification, adding new features and launching them without announcement in order to try to get the upper hand over the other. Both sides would often refuse to implement one-another’s new tags unless they were forced to by widespread adoption by page authors, instead promoting their own competing mechanisms11.

Between adding this new language feature to their browser and writing this page, Netscape’s market share had fallen from around 80% to around 55%, and most of their losses were picked

up by IE. Using <multicol> would have made their page look worse in Microsoft’s hot up-and-coming

browser, which wouldn’t have helped them persuade more people to download a copy of Navigator and certainly wouldn’t be a good image on a soon-to-launch (any day now!) page about

best-practice on the Web! So Netscape’s authors opted for the dominant, cross-platform solution on this page12.

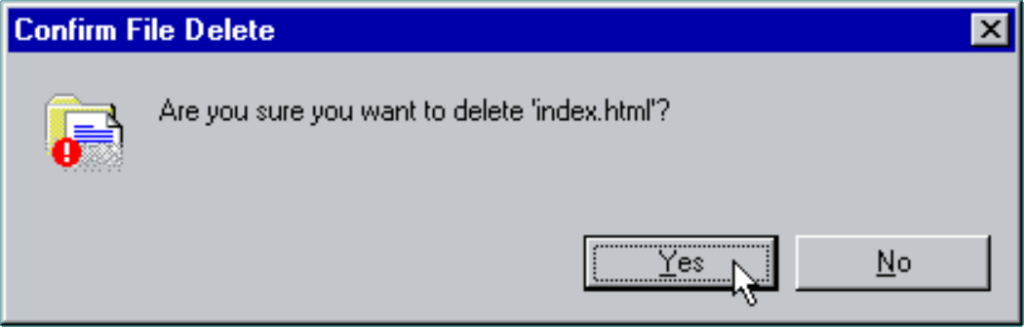

Anyway, let’s fast-forward a bit and see this project finally leave its “under construction” phase and launch!

Oh. It’s gone.

Sometime between October 1997 and February 1998 the long promised “Web Site Stories” section of Netscape Columns quietly disappeared from the website. Presumably, it never published a single article, instead remaining a perpetual “Coming Soon” page right up until the day it was deleted.

I’m not sure if there’s a better metaphor for Netscape’s general demeanour in 1998 – the year in which they finally ceased to be the dominant market leader in web browsers – than the quiet deletion of a page about how Netscape customers are making the best of the Web. This page might not have been important, or significant, or even completed, but its disappearance may represent Netscape’s refocus on trying to stay relevant in the face of existential threat.

Of course, Microsoft won the First Browser War. They did so by pouring a fortune’s worth of developer effort into staying technologically one-step ahead, refusing to adopt standards proposed by their rival, and their unprecedented decision to give away their browser for free13.

Footnotes

1 Yes, we used to write “Web sites” as two words. We also used to consistently capitalise the words Web and Internet. Some of us still do so.

2 In case it’s not clear, this blog post is going to be as much about little-known and archaic Web design techniques as it is about Netscape’s website.

3 This is a white lie. CSS was first proposed almost at the same time as the Web! Microsoft Internet Explorer was first to deliver a partial implementation of the initial standard, late in 1996, but Netscape dragged their heels, perhaps in part because they’d originally backed a competing standard called JavaScript Style Sheets (JSSS). JSSS had a lot going for it: if it had enjoyed widespread adoption, for example, we’d have had the equivalent of CSS variables a full twenty years earlier! In any case, back in 1996 you definitely wouldn’t want to rely on CSS support.

4 Wondering where the text and link colours come from? <body bgcolor="#ffffff"

text="#000000" link="#0000ff" vlink="#ff0000" alink="#ff0000">. Yes really, that’s where we used to put our colours.

5 Personally, I really loved the aesthetic Netscape touted when using Times New Roman (or whatever serif font was available on your computer: webfonts weren’t a thing yet) with temporary tweaks to font sizes, and I copied it in some of my own sites. If you look back at my 2018 blog post celebrating two decades of blogging, where I’ve got a screenshot of my blog as it looked circa 1999, you’ll see that I used exactly this technique for the ordinal suffixes on my post dates! On the same post, you’ll see that I somewhat replicated the “feel” of it again in my 2011 design, this time using a stylesheet.

6 There’s a whole section of Cameron’s World dedicated to “under construction” banners, and that’s a beautiful thing!

7 The idea of “garden and stream” is that you publish early and often, refining as you go, in your garden, which can act as an extension of whatever notetaking system you use already, but publish mostly “finished” content to your (chronological) stream. I see an increasing number of IndieWeb bloggers going down this route, but I’m not convinced that it’s for me.

8 Another white lie. PHP was

released way back in 1995 and even the very first version supported something a lot like server-side includes, using the syntax <!--include /file/name.html-->. But it was a little computationally-intensive to run willy-nilly.

9 Server-side imagemaps are enjoying a bit of a renaissance on .onion services, whose visitors often keep JavaScript disabled, to make image-based CAPTCHAs. Simply show the visitor an image and describe the bit you want them to click on, e.g. “the blue pentagon with one side missing”, then compare the coordinates of the pixel they click on to the knowledge of the right answer. Highly-inaccessible, of course, but innovative from a purely-technical perspective.

10 Nowadays, use of tables for layout – or, indeed, for anything other than tabular

data – is very-much frowned upon: it’s often bad for accessibility and responsive design. But back before we had the features granted to us by the modern Web, it was literally

the only way to get content to appear side-by-side on a page, and designers got incredibly creative about how they misused tables to lay out content, especially as

browsers became more-sophisticated and began to support cells that spanned multiple rows or columns, tables “nested” within one another, and background images.

11 It was a horrible time to be a web developer: having to make hacky workarounds in order to make use of the latest features but still support the widest array of browsers. But I’d still take that over the horrors of rendering engine monoculture!

12 Or maybe they didn’t even think about it and just copy-pasted from somewhere else on their site. I’m speculating.

13 This turned out to be the master-stroke: not only did it partially-extricate Microsoft from their agreement with Spyglass Inc., who licensed their browser engine to Microsoft in exchange for a percentage of sales value, but once Microsoft started bundling Internet Explorer with Windows it meant that virtually every computer came with their browser factory-installed! This strategy kept Microsoft on top until Firefox and Google Chrome kicked-off the Second Browser War in the early 2010s. But that’s another story.

[Bloganuary] Sportsball!

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What are your favourite sports to watch and play?

I’ve never really been very sports-motivated. I enjoy casually participating, but I can’t really see the attraction in spectating most sports, most of the time1.

My limited relationship with sports

There are several activities I enjoy doing that happen to overlap with sports: swimming, cycling, etc., but I’m not doing them as sports. By which I mean: I’m not doing them competitively (and I don’t expect that to change).

I used to appreciate a game of badminton once in a while, and I’ve plenty of times enjoyed kicking a ball around with whoever’s there (party guests… the kids… the dog…2). But again, I’ve not really done any competitive sports since I used to play rugby at school, way back in the day3.

I guess I don’t really see the point in spectating sports that I don’t have any personal investment in. Which for me means that it’d have to involve somebody I care about!

A couple of dozen strangers running about for 90 minutes does nothing for me, because I haven’t the patriotism to care who wins or loses. But put one of my friends or family on the pitch and I might take an interest4!

What went wrong with football, for example

In some ways, the commercialisation of sport seems to me to be… just a bit sad?

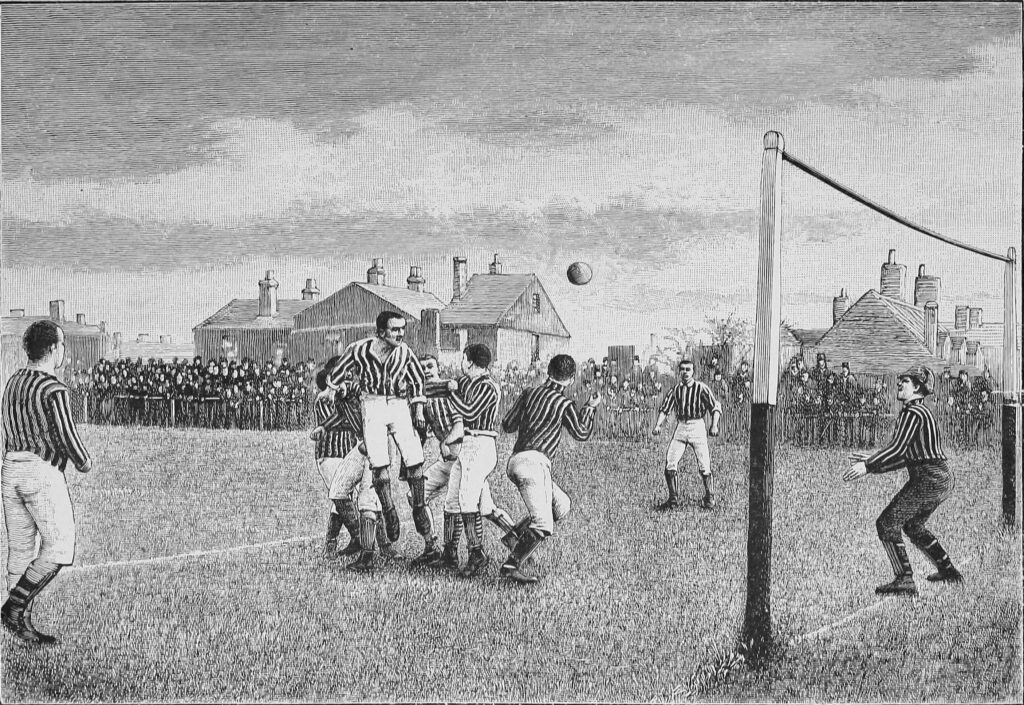

Take soccer (association football), for example, whose explosive success in the United Kingdom helped bolster the worldwide appeal it enjoys today.

Up until the late 19th century soccer was exclusively an amateur sport: people played on teams on evenings and weekends and then went back to their day jobs the rest of the time. In fact, early football leagues in the UK specifically forbade professional players!5

As leagues grew beyond local inter-village tournaments and reached the national stage, this approach gave an unfair advantage to teams in the South of England over those in the North and in Scotland. You see, the South had a larger proportion of landed gentry (who did not need to go back to a “day job” and could devote more of their time to practice) and a larger alumni of public schools (which had a long history with the sport in some variation or another)!6

Clamour from the Northern teams to be allowed to employ professional players eventually lead to changes in the rules to permit paid team members so long as they lived within a certain distance of the home pitch7. The “locality” rule for professional players required that the player had been born, or had lived for two years, within the vicinity of the club. People turned up to cheer on the local boys8, paid their higher season ticket prices to help fund not only the upkeep of the ground and the team’s travel but now also their salaries. Still all fine.

Things went wrong when the locality rule stopped applying. Now teams were directly competing with one another for players, leading to bidding wars. The sums of money involved in signing players began to escalate. Clubs merged (no surprise that so many of those “Somewheretown United” teams sprung up around this period) and grew larger and begun marketing in new ways to raise capital: replica kits, televised matches, sponsorship deals… before long running a football team was more about money than location.

And that’s where we are today, and why the odds are good that your local professional football team doesn’t have any players that you or anybody you know will ever meet in person.

That’s a bit of a long a way to say “nah, I’m not terribly into sports”, isn’t it?

Footnotes

1 I even go to efforts to filter sports news out of my RSS subscriptions!

2 The dog loves trying to join in a game of football and will happily push the ball up and down the pitch, but I don’t think she understands the rules and she’s indecisive about which team she’s on. Also, her passing game leaves a lot to be desired, and her dribbling invariably leaves the ball covered in drool.

3 And even then, my primary role in the team was to be a chunky dirty-fighter of a player who got in the way of the other team and wasn’t afraid to throw his weight around.

4 Unless it’s cricket. What the fuck is cricket supposed to be about? I have spectated a cricket match featuring people I know and I still don’t see the attraction.

5 Soccer certainly wasn’t the first sport to “go professional” in the UK; cricket was way ahead of it, for example. But it enjoys such worldwide popularity today that I think it’s a good example to use in a history lesson.

6 I’m not here to claim that everything that’s wrong with the commercialisation of professional football can be traced to the North/South divide in England.. but we can agree it’s a contributing factor, right?

7 Here’s a fun aside: this change to the rules about employment of professional players didn’t reach Scotland until 1893, and many excellent Scottish players – wanting to make a career of their hobby – moved to England in order to join English teams as professional players. In the 1890s, the majority of the players at Preston North End (whose stadium I lived right around the corner of for over a decade) were, I understand, Scottish!

8 And girls! Even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were women’s football teams: Dick, Kerr Ladies F.C., also from Preston (turns out there’s a reason the National Football Museum was, until 2012, located there), became famous for beating local men’s teams and went on to represent England internationally. But in 1921 the FA said that “the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and should not be encouraged”, and banned from the leagues any men’s team that shared their pitch with a women’s team. The ban was only rescinded in 1971. Thanks, FA.

[Bloganuary] Harcourt Manor

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

Name an attraction or town close to home that you still haven’t got around to visiting.

I live a just outside the village of Stanton Harcourt in West Oxfordshire. It’s tiny, but it’s historically-significant, and there’s one very-obvious feature that I see several times a week but have never been inside of.

When William the Conqueror came to England, he divvied up large parts of the country and put them under the authority of the friends who helped him with his invasion, dioceses of the French church, or both. William’s half-brother Odo1 did particularly well: he was appointed Earl of Kent and got huge swathes of land (second only to the king), including the village of Stanton and the fertile farmlands that surrounded it.

Odo later fell out of favour after he considered challenging Pope Gregory VII to fisticuffs or somesuchthing, and ended up losing a lot of his lands. Stanton eventually came to be controlled by Robert of Harcourt, whose older brother Errand helped William at the Battle of Hastings but later died without any children. Now under the jurisdiction of the Harcourt family, the village became known as Stanton Harcourt.

The Harcourt household at Stanton in its current form dates from around the 15th/16th century. Perhaps its biggest claim to fame is that Alexander Pope lived in the tower (now called Pope’s Tower) while he was translating the Illiad into a heroic couplet-format English. Anyway: later that same century the Harcourts moved to Nuneham Courtenay, on the other side of Oxford2 the house fell into disrepair.

It’s a piece of local history right on my doorstep that I haven’t yet had the chance to explore. Maybe some day!

Footnotes

1 If you’ve heard of Odo before, it’s likely because he was probably the person who commissioned the Bayeux Tapestry, which goes a long way to explaining why he and his entourage feature so-heavily on it.

2 The place the Harcourt family moved to is next to what is now… Harcourt Arboretum! Now you know where the name comes from.

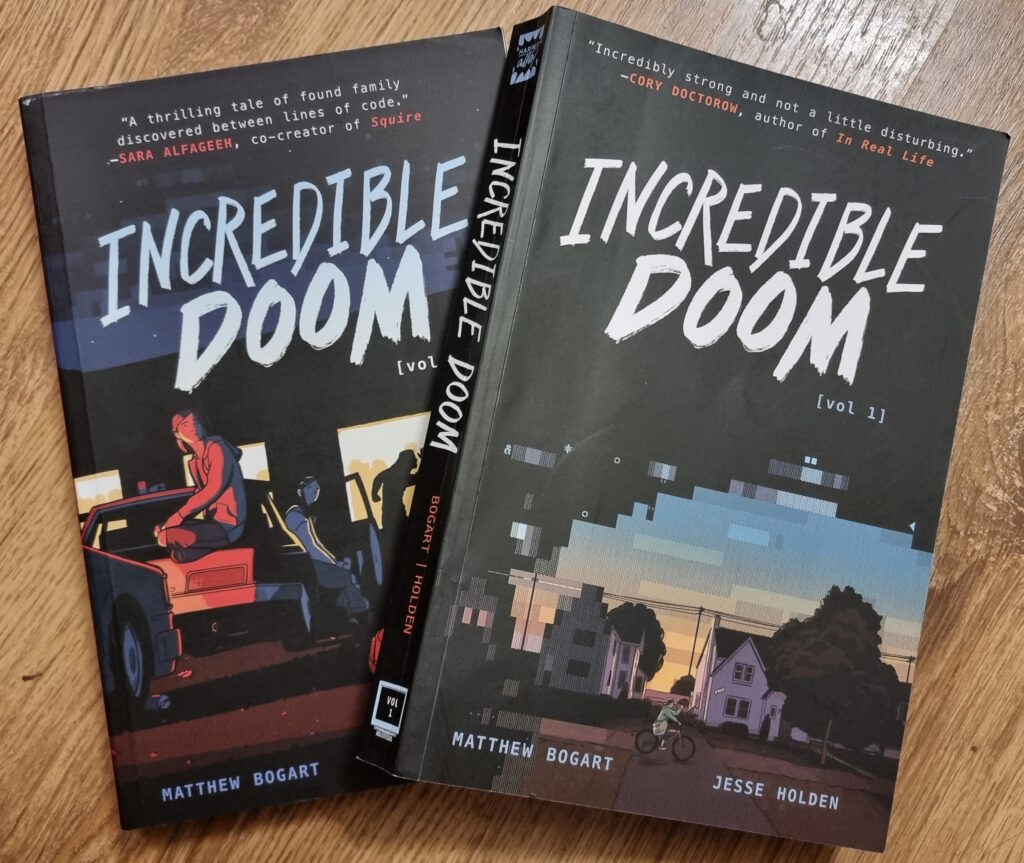

Incredible Doom

I just finished reading Incredible Doom volumes 1 and 2, by Matthew Bogart and Jesse Holden, and man… that was a heartwarming and nostalgic tale!

Set in the early-to-mid-1990s world in which the BBS is still alive and kicking, and the Internet’s gaining traction but still lacks the “killer app” that will someday be the Web (which is still new and not widely-available), the story follows a handful of teenagers trying to find their place in the world. Meeting one another in the 90s explosion of cyberspace, they find online communities that provide connections that they’re unable to make out in meatspace.

It touches on experiences of 90s cyberspace that, for many of us, were very definitely real. And while my online “scene” at around the time that the story is set might have been different from that of the protagonists, there’s enough of an overlap that it felt startlingly real and believable. The online world in which I – like the characters in the story – hung out… but which occupied a strange limbo-space: both anonymous and separate from the real world but also interpersonal and authentic; a frontier in which we were still working out the rules but within which we still found common bonds and ideals.

Anyway, this is all a long-winded way of saying that Incredible Doom is a lot of fun and if it sounds like your cup of tea, you should read it.

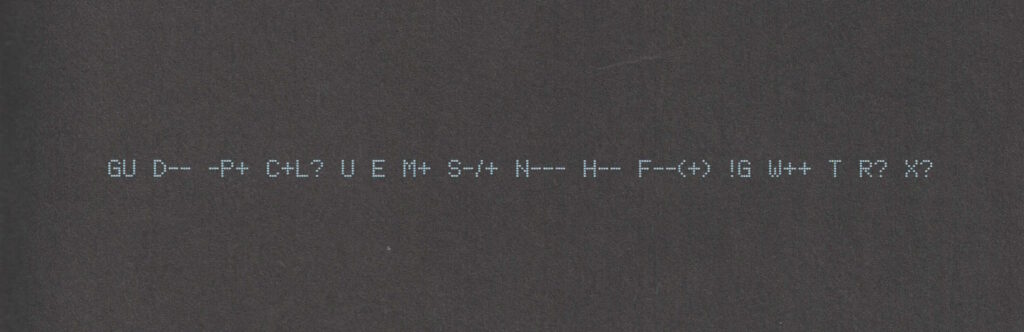

Also: shortly after putting the second volume down, I ended up updating my Geek Code for the first time in… ooh, well over a decade. The standards have moved on a little (not entirely in a good way, I feel; also they’ve diverged somewhat), but here’s my attempt:

----- BEGIN GEEK CODE VERSION 6.0 ----- GCS^$/SS^/FS^>AT A++ B+:+:_:+:_ C-(--) D:+ CM+++ MW+++>++ ULD++ MC+ LRu+>++/js+/php+/sql+/bash/go/j/P/py-/!vb PGP++ G:Dan-Q E H+ PS++ PE++ TBG/FF+/RM+ RPG++ BK+>++ K!D/X+ R@ he/him! ----- END GEEK CODE VERSION 6.0 -----

Footnotes

1 I was amazed to discover that I could still remember most of my Geek Code syntax and only had to look up a few components to refresh my memory.