My love of the yesterweb forced me to teach myself just-enough Blender to make an animation for a stupid thing: an 88×31 button representing “me” (and, I suppose, my blog, whenever I next end up redesigning its theme).

Tag: nostalgia

INSULTS.COM

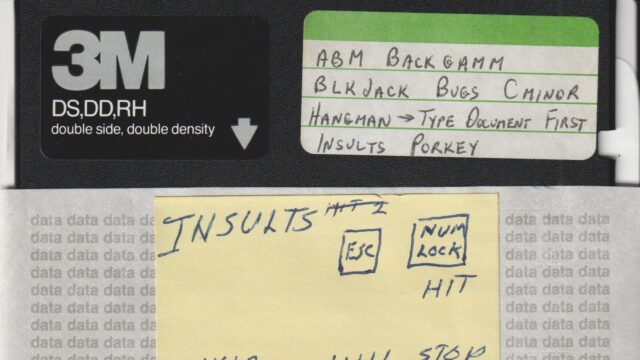

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, I had a collection of 5¼” and later 3½” floppy disks1 on which were stored a variety of games and utilities that I’d collected over the years2.

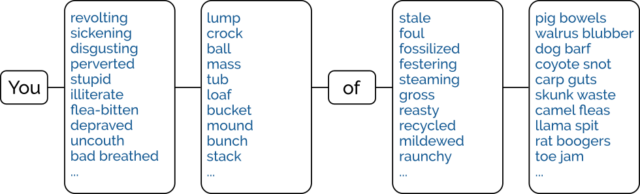

I remember that at some point I acquired a program called INSULTS.COM. When executed, this tool would spoof a basic terminal prompt and then, when the user pressed any key,

output a randomly-generated assortment of crude insults.

As far as prank programs go, it was far from sophisticated. I strongly suspect that the software, which was released for free in 1983, was intended to be primarily a vehicle to promote

sales of a more-complex set of tools called PRANKS, which was advertised within.

In any case: as a pre-pubescent programmer I remember being very interested in the mechanism by which INSULTS.COM was generating its output.

Of course, nowadays I understand reverse-engineering better than I did as a child. So I downloaded a copy of INSULTS.COM from this Internet Archive image, ran it through Strings, and pulled out the data.

Easy!

Then I injected the strings into Perchance to produce a semi-faithful version of the application that you can enjoy today.

Why did I do this? Why do I do anything? Reimplementing a 42-year-old piece of DOS software that nobody remembers is even stranger than that time I reimplemented a 16-year old Flash advertisement! But I hope it gave you a moment’s joy to be told that you’re… an annoying load of festering parrot droppings, or whatever.

Footnotes

1 Also some 3″ floppy disks – a weird and rare format – but that’s another story.

2 My family’s Amstrad PC1512 had two 5¼” disk drives, which made disk-to-disk copying much easier than it was on computers with a single disk drive, on which you’d have to copy as much data as possible to RAM, swap disks to write what had been copied so far, swap disks back again, and repeat. This made it less-laborious for me to clone media than it was for most other folks I knew.

3 Assuming the random number generator is capable of generating a sufficient diversity of

seed values, the claim is correct: by my calculation, INSULTS.COM can generate 22,491,833 permutations of insults.

God’s Adviser

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Of all the discussions I’ve ever been involved with on the subject of religion, the one I’m proudest of was perhaps also one of the earliest.

Let me tell you about a time that, as an infant, I got sent out of my classroom because I wouldn’t stop questioning the theological ramifications of our school nativity play.

I’m aware that I’ve got readers from around the world, and Christmas traditions vary, so let’s start with a primer. Here in the UK, it’s common1 at the end of the school term before Christmas for primary schools to put on a “nativity play”. A group of infant pupils act out an interpretation of the biblical story of the birth of Jesus: a handful of 5/6-year-olds playing the key parts of, for example, Mary, Joseph, an innkeeper, some angels, maybe a donkey, some wise men, some shepherds, and what-have-you.

As with all theatre performed by young children, a nativity play straddles the line between adorable and unbearable. Somehow, the innkeeper – who only has one line – forgets to say “there is no room at the inn” and so it looks like Mary and Joseph just elect to stay in the barn, one of the angels wets herself in the middle of a chorus, and Mary, bored of sitting in the background having run out of things to do, idly swings the saviour of mankind round and around, holding him by his toe. It’s beautiful2.

I was definitely in a couple of different nativity plays as a young child, but one in particular stands out in my memory.

In order to put a different spin on the story of the first Christmas3, one year my school decided to tell a different, adjacent story. Here’s a summary of the key beats of the plot, as I remember it:

- God is going to send His only son to Earth and wants to advertise His coming.

- “What kind of marker can he put in the sky to lead people to the holy infant’s birthplace?”, He wonders.

- So He auditions a series of different natural phenomena:

- The first candidate is a cloud, but its pitch is rejected because… I don’t remember: it’ll blow away or something.

- Another candidate was a rainbow, but it was clearly derivative of an earlier story, perhaps.

- After a few options, eventually God settles on a star. Hurrah!

- Some angels go put the star in the right place, shepherds and wise men go visit Mary and her family, and all that jazz.

So far, totally on-brand for a primary school nativity play but with 50% more imagination than the average. Nice.

I was cast as Adviser #1, and that’s where things started to go wrong.

The part of God was played by my friend Daniel, but clearly our teacher figured that he wouldn’t be able to remember all of his lines4 and expanded his role into three: God, Adviser #1, and Adviser #2. After each natural phenomenon explained why it would be the best, Adviser #1 and Adviser #2 would each say a few words about the candidate’s pros and cons, providing God with the information He needed to make a decision.

To my young brain, this seemed theologically absurd. Why would God need an adviser?5

“If He’s supposed to be omniscient, why does God need an adviser, let alone two?” I asked my teacher6.

The answer was, of course, that while God might be capable of anything… if the kid playing Him managed to remember all of his lines then that’d really be a miracle. But I’d interrupted rehearsals for my question and my teacher Mrs. Doyle clearly didn’t want to explain that in front of the class.

But I wouldn’t let it go:

- “But Miss, are we saying that God could make mistakes?”

- “Couldn’t God try out the cloud and the rainbow and just go back in time when He knows which one works?”

- “Why does God send an angel to tell the shepherds where to go but won’t do that for the kings?”

- “Miss, don’t the stars move across the sky each night? Wouldn’t everybody be asking questions about the bright one that doesn’t?”

- “Hang on, what’s supposed to have happened to the Star of Bethlehem after God was done with it? Did it have planets? Did those planets… have life?”

In the end I had to be thrown out of class. I spent the rest of that rehearsal standing in the corridor.

And it was totally worth it for this anecdote.

Footnotes

1 I looked around to see if the primary school nativity play was still common, or if the continuing practice at my kids’ school shows that I’m living in a bubble, but the only source I could find was a 2007 news story that claims that nativity plays are “under threat”… by The Telegraph, who I’d expect to write such a story after, I don’t know, the editor’s kids decided to put on a slightly-more-secular play one year. Let’s just continue to say that the school nativity play is common in the UK, because I can’t find any reliable evidence to the contrary.

2 I’ve worked onstage and backstage on a variety of productions, and I have nothing but respect for any teacher who, on top of their regular workload and despite being unjustifiably underpaid, volunteers to put on a nativity play. I genuinely believe that the kids get a huge amount out of it, but man it looks like a monumental amount of work.

3 And, presumably, spare the poor parents who by now had potentially seen children’s amateur dramatics interpretations of the same story several times already.

4 Our teacher was probably correct.

5 In hindsight, my objection to this scripting decision might actually have been masking an objection to the casting decision. I wanted to play God!

6 I might not have used the word “omniscient”, because I probably didn’t know the word yet. But I knew the concept, and I certainly knew that my teacher was on spiritually-shaky ground to claim both that God knew everything and God needed an advisor.

Yr Wyddfa’s First Email

On Wednesday, Vodafone announced that they’d made the first ever satellite video call from a stock mobile phone in an area with no terrestrial signal. They used a mountain in Wales for their experiment.

It reminded me of an experiment of my own, way back in around 1999, which I probably should have made a bigger deal of. I believe that I was the first person to ever send an email from the top of Yr Wyddfa/Snowdon.

Nowadays, that’s an easy thing to do. You pull your phone out and send it. But back then, I needed to use a Psion 5mx palmtop, communicating over an infared link using a custom driver (if you ever wondered why I know my AT-commands by heart… well, this isn’t exactly why, but it’s a better story than the truth) to a Nokia 7110 (fortunately it was cloudy enough to not interfere with the 9,600 baud IrDA connection while I positioned the devices atop the trig point), which engaged a GSM 2G connection, over which I was able to send an email to myself, cc:’d to a few friends.

It’s not an exciting story. It’s not even much of a claim to fame. But there you have it: I was (probably) the first person to send an email from the summit of Yr Wyddfa. (If you beat me to it, let me know!)

Can AI retroactively fix WordPress tags?

I’ve a notion that during 2025 I might put some effort into tidying up the tagging taxonomy on my blog. There’s a few tags that are duplicates (e.g.

ai and artificial intelligence) or that exhibit significant overlap (e.g. dog and dogs), or that were clearly created when I

speculated I’d write more on the topic than I eventually did (e.g. homa night, escalators1,

or nintendo) or that are just confusing and weird (e.g. not that bacon sandwich picture).

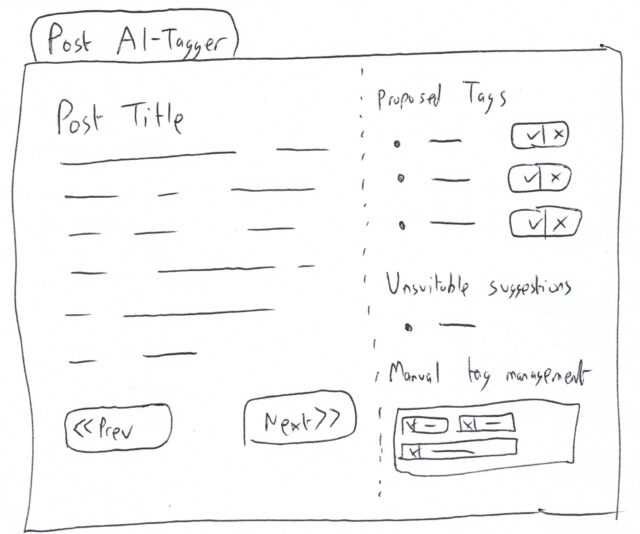

Retro-tagging with AI

One part of such an effort might be to go back and retroactively add tags where they ought to be. For about the first decade of my blog, i.e. prior to around 2008, I rarely used tags to categorise posts. And as more tags have been added it’s apparent that many old posts even after that point might be lacking tags that perhaps they ought to have2.

I remain sceptical about many uses of (what we’re today calling) “AI”, but one thing at which LLMs seem to do moderately well is summarisation3. And isn’t tagging and categorisation only a stone’s throw away from summarisation? So maybe, I figured, AI could help me to tidy up my tagging. Here’s what I was thinking:

- Tell an LLM what tags I use, along with an explanation of some of the quirkier ones.

- Train the LLM with examples of recent posts and lists of the tags that were (correctly, one assumes) applied.

- Give it the content of blog posts and ask what tags should be applied to it from that list.

- Script the extraction of the content from old posts with few tags and run it through the above, presenting to me a report of what tags are recommended (which could then be coupled with a basic UI that showed me the post and suggested tags, and “approve”/”reject” buttons or similar.

Extracting training data

First, I needed to extract and curate my tag list, for which I used the following SQL4:

SELECT COUNT(wp_term_relationships.object_id) num, wp_terms.slug FROM wp_term_taxonomy LEFT JOIN wp_terms ON wp_term_taxonomy.term_id = wp_terms.term_id LEFT JOIN wp_term_relationships ON wp_term_taxonomy.term_taxonomy_id = wp_term_relationships.term_taxonomy_id WHERE wp_term_taxonomy.taxonomy = 'post_tag' AND wp_terms.slug NOT IN ( -- filter out e.g. 'rss-club', 'published-on-gemini', 'dancast' etc. -- these are tags that have internal meaning only or are already accurately applied 'long', 'list', 'of', 'tags', 'the', 'ai', 'should', 'never', 'apply' ) GROUP BY wp_terms.slug HAVING num > 2 -- filter down to tags I actually routinely use ORDER BY wp_terms.slug

published on gemini if they’re to appear on gemini://danq.me/ and

dancast if they embed an episode of my podcast. I filtered these out because I never want the AI to suggest applying them.

I took my output and dumped it into a list, and skimmed through to add some clarity to some tags whose purpose might be considered ambiguous, writing my explanation of each in parentheses afterwards. Here’s a part of the list, for example:

- …

- puzzles

- python

- q (explicitly about my unusual surname, which is just the letter Q)

- qparty

- quake

- quakers

- quantum-physics

- quotes

- racing

- racism

- radio

- raid (about RAID storage devices, as might be used in a NAS computer)

- rails (Ruby on Rails)

- rain

- rambling

- …

Prompt derivation

I used that list as the basis for the system message of my initial prompt:

Suggest topical tags from a predefined list that appropriately apply to the content of a given blog post. # Steps 1. **Read the Blog Post**: Carefully read through the provided content of the blog post to identify its main themes and topics. 2. **Analyse Key Aspects**: Identify key topics, themes, or subjects discussed in the blog post. 3. **Match with Tags**: Compare these identified topics against the list of available tags. 4. **Select Appropriate Tags**: Choose tags that best represent the main topics and themes of the blog post. # Output Format Provide a list of suggested tags. Each tag should be presented as a single string. Multiple tags should be separated by commas. # Allowed Tags Tags that can be suggested are as follows. Text in parentheses are not part of the tag but are a description of the kinds of content to which the tag ought to be applied: - aberdyfi - aberystwyth - ... - youtube - zoos # Examples **Input:** The rapid advancement of AI technology has had a significant impact on my industry, even on the ways in which I write my blog posts. This post, for example, used AI to help with tagging. **Output:** ai, technology, blogging, meta, work ...(other examples)... # Notes - Ensure that all suggested tags are relevant to the key themes of the blog post. - Tags should be selected based on their contextual relevance and not just keyword matching.

This system prompt is somewhat truncated, but you get the idea.

Now I was ready to give it a go with some real data. As an initial simple and short (and therefore also computationally cheap) experiment, I tried feeding it a note I wrote last week about the interrobang’s place in the Spanish language, and in Unicode.

That post already has the following tags (but this wasn’t disclosed to the AI in its training set; it had to work from scratch): children, language, languages (a bit of a redundancy there!), spain, and unicode.

Testing it out

Let’s see what the AI suggests:

curl https://api.openai.com/v1/chat/completions \ -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ -H "Authorization: Bearer $OPENAI_TOKEN" \ -d '{ "model": "gpt-4o-mini", "messages": [ { "role": "system", "content": [ { "type": "text", "text": "[PROMPT AS DESCRIBED ABOVE]" } ] }, { "role": "user", "content": [ { "type": "text", "text": "My 8-year-old asked me \"In Spanish, I need to use an upside-down interrobang at the start of the sentence‽\" I assume the answer is yes A little while later, I thought to check whether Unicode defines a codepoint for an inverted interrobang. Yup: ‽ = U+203D, ⸘ = U+2E18. Nice. And yet we dont have codepoints to differentiate between single-bar and double-bar \"cifrão\" dollar signs..." } ] } ], "response_format": { "type": "text" }, "temperature": 1, "max_completion_tokens": 2048, "top_p": 1, "frequency_penalty": 0, "presence_penalty": 0 }'

curl meant I quickly ran up against some Bash escaping issues, but set +H and a little massaging of the blog post content

seemed to fix it.

GPT-4o-mini

When I ran this query against the gpt-4o-mini model, I got back: unicode, language, education, children, symbols.

That’s… not ideal. I agree with the tags unicode, language, and children, but this isn’t really about education. If I tagged

everything vaguely educational on my blog with education, it’d be an even-more-predominant tag than geocaching is! I reserve that tag for things that relate

specifically to formal education: but that’s possibly something I could correct for with a parenthetical in my approved tags list.

symbols, though, is way out. Sure, the post could be argued to be something to do with symbols… but symbols isn’t on the approved tag list in

the first place! This is a clear hallucination, and that’s pretty suboptimal!

Maybe a beefier model will fare better…

GPT-4o

I switched gpt-4o-mini for gpt-4o in the command above and ran it again. It didn’t take noticeably longer to run, which was pleasing.

The model returned: children, language, unicode, typography. That’s a big improvement. It no longer suggests education,

which was off-base, nor symbols, which was a hallucination. But it did suggest typography, which is a… not-unreasonable suggestion.

Neither model suggested spain, and strictly-speaking they were probably right not to. My post isn’t about Spain so much as it’s about Spanish. I don’t

have a specific tag for the latter, but I’ve subbed in the former to “connect” the post to ones which are about Spain, but that might not be ideal. Either way: if this is how

I’m using the tag then I probably ought to clarify as such in my tag list, or else add a note to the system prompt to explain that I use place names as the tags for posts about

the language of those places. (Or else maybe I need to be more-consistent in my tagging).

I experimented with a handful of other well-tagged posts and was moderately-satisfied with the results. Time for a more-challenging trial.

This time, with feeling…

Next, I decided to run the code against a few blog posts that are in need of tags. At this point, I wasn’t quite ready to implement a UI, so I just adapted my little hacky Bash script and copy-pasted HTML-stripped post contents directly into it.

I ran against three old posts:

Hospitals (June 2006)

In this post, I shared that my grandmother and my coworker had (independently) been taken into hospital. It had no tags whatsoever.

The AI suggested the tags hospital, family, injury, work, weddings, pub, humour. Which at

a glance, is probably a superset of the tags that I’d have considered, but there’s a clear logic to them all.

It clearly picked out weddings based on a throwaway comment I made about a cousin’s wedding, so I disagree with that one: the post isn’t strictly about weddings

just because it mentions one.

pub could go either way. It turns out my coworker’s injury occurred at or after a trip to the pub the previous night, and so its relevance is somewhat unknowable from this

post in isolation. I think that’s a reasonable suggestion, and a great example of why I’d want any such auto-tagging system to be a human assistant (suggesting

candidate tags) and not a fully-automated system. Interesting!

Finally, you might think of humour as being a little bit sarcastic, or maybe overly-laden with schadenfreude. But the blog post explicitly states that my coworker

“carefully avoided saying how he’d managed to hurt himself, which implies that it’s something particularly stupid or embarrassing”, before encouraging my friends to speculate on it.

However, it turns out that humour isn’t one of my existing tags at all! Boo, hallucinating AI!

I ended up applying all of the AI’s suggestions except weddings and humour. I also applied smartdata, because that’s where I worked (the AI couldn’t have been expected to guess that without context, though!).

Catch-Up: Concerts (June 2005)

This post talked about Ash and I’s travels around the UK to see REM and Green Day in concert5 and to the National Science Museum in London where I discovered that Ash was prejudiced towards… carrot cake.

The AI suggested: concerts, travel, music, preston, london, science museum, blogging.

Those all seemed pretty good at a first glance. Personally, I’d forgotten that we swung by Preston during that particular grand tour until the AI suggested the tag, and then I had to

look back at the post more-carefully to double-check! blogging initially seemed like a stretch given that I was only blogging about not having blogged much, but on

reflection I think I agree with the robot on this one, because I did explicitly link to a 2002 page that fell off the Internet only a few years ago about

the pointlessness of blogging. So I think it counts.

science museum is a big fail though. I don’t use that tag, but I do use the tag museum. So close, but not quite there, AI!

I applied all of its suggestions, after switching museum in place of science museum.

Geeky Winnage With Bluetooth (September 2004)

I wrote this blog post in celebration of having managed to hack together some stuff to help me remote-control my PC from my phone via Bluetooth, which back then used to be a challenge, in the hope that this would streamline pausing, playing, etc. at pizza-distribution-time at Troma Night, a weekly film night I hosted back then.

It already had the tag technology, which it inherited from a pre-tagging evolution of my blog which used something akin to categories (of which only one

could be assigned to a post). In addition to suggesting this, the AI also picked out the following options: bluetooth, geeky, mobile, troma

night, dvd, technology, and software.

The big failure here was dvd, which isn’t remotely one of my tags (and probably wouldn’t apply here if it were: this post isn’t about DVDs; it barely even mentions

them). Possibly some prompt engineering is required to help ensure that the AI doesn’t make a habit of this “include one tag not from the approved list, every time” trend.

Apart from that it’s a pretty solid list. Annoyingly the AI suggested mobile, which isn’t an approved tag, instead of mobiles, which is. That’s probably a

tokenisation fault, but it’s still annoying and a reminder of why even a semi-automated “human-checked” system would need a safety-check to ensure that no absent tags are

allowed through to the final stage of approval.

This post!

As a bonus experiment, I tried running my code against a version of this post, but with the information about the AI’s own prompt and the examples removed (to reduce the risk

of confusion). It came up with: ai, wordpress, blogging, tags, technology, automation.

All reasonable-sounding choices, and among those I’d made myself… except for tags and automation which, yet again, aren’t among tags that I use. Unless this

tendency to hallucinate can be reined-in, I’m guessing that this tool’s going to continue to have some challenges when used on longer posts like this one.

Conclusion and next steps

The bottom line is: yes, this is a job that an AI can assist with, but no, it’s not one that it can do without supervision. The laser-focus with which gpt-4o was able to

pick out taggable concepts, faster than I’d have been able to do for the same quantity of text, shows that there’s potential here, but it’s not yet proven itself enough of a time-saver

to justify me writing a fluffy UI for it.

However, I might expand on the command-line tools I’ve been using in order to produce a non-interactive list of tagging suggestions, and use that to help inform my work as I tidy up the tags throughout my blog.

You still won’t see any “AI-authored” content on this site (except where it’s for the purpose of talking about AI-generated content, and it’ll always be clearly labelled), and I can’t see that changing any time soon. But I’ll admit that there might be some value in AI-assisted curation and administration, so long as there’s an informed human in the loop at all times.

Footnotes

1 Based on my tagging, I’ve apparently only written about escalators once, while playing Pub Jenga at Robin‘s 21st birthday party. I can’t imagine why I thought it deserved a tag.

2 There are, of course, various other people trying similar approaches to this and similar problems. I might have tried one of them, were it not for the fact that I’m not quite as interested in solving the problem as I am in understanding how one might use an AI to solve the problem. It’s similar to how I don’t enjoy doing puzzles like e.g. sudoku as much as I enjoy writing software that optimises for solving such puzzles. See also, for example, how I beat my children at Mastermind or what the hardest word in Hangman is or my various attempts to avoid doing online jigsaws.

3 Let’s ignore for a moment the farce that was Apple’s attempt to summarise news headlines, shall we?

4 Essentially the same SQL, plus WordClouds.com, was used to produce the word cloud grapic!

5 Two separate concerts, but can you imagine‽ 🤣

Note #24906

As the kids grow older… someday our final soft play session – something we used to do all the time, and now do only rarely – will be in the past.

But for now, at least, it remains a chaotic way to tire them out on a morning!

3D Workers Island

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

If you’ve come across Tony Domenico’s work before it’s probably as a result of web horror video series Petscop.

3D Workers Island… isn’t quite like that (though quick content warning: it does vaugely allude to child domestic

abuse). It’s got that kind of alternative history/”found footage webpage” feel to it that I enjoyed so much about the Basilisk

collection. It’s beautifully and carefully made in a way that brings its world to life, and while I found the overall story slightly… incomplete?… I enjoyed the application of

its medium enough to make up for it.

Best on desktop, but tolerable on a large mobile in landscape mode. Click each “screenshot” to advance.

Firsts and Lasts

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

A lot of attention is paid, often in retrospect, to the experience of the first times in our lives. The first laugh; the first kiss; the first day at your job1. But for every first, there must inevitably be a last.

I recall a moment when I was… perhaps the age our eldest child is now. As I listened to the bats in our garden, my mother told me about how she couldn’t hear them as clearly as she could when she was my age. The human ear isn’t well-equipped to hear that frequency that bats use, and while children can often pick out the sounds, the ability tends to fade with age.

This recollection came as I stayed up late the other month to watch the Perseids. I lay in the hammock in our garden under a fabulously clear sky as the sun finished setting, and – after being still and quiet for a time – realised that the local bat colony were out foraging for insects. They flew around and very close to me, and it occurred to me that I couldn’t hear them at all.

There must necessarily have been a “last time” that I heard a bat’s echolocation. I remember a time about ten years ago, at the first house in Oxford of Ruth, JTA and I (along with Paul), standing in the back garden and listening to those high-pitched chirps. But I can’t tell you when the very last time was. At the time it will have felt unremarkable rather than noteworthy.

First times can often be identified contemporaneously. For example: I was able to acknowledge my first time on a looping rollercoaster at the time.

I wonder what it would be like if we had the same level of consciousness of last times as we did of firsts. How differently might we treat a final phone call to a loved one or the ultimate visit to a special place if we knew, at the time, that there would be no more?

Would such a world be more-comforting, providing closure at every turn? Or would it lead to a paralytic anticipatory grief: “I can’t visit my friend; what if I find out that it’s the last time?”

Footnotes

1 While watching a wooden train toy jiggle down a length of string, reportedly; Sarah Titlow, behind the school outbuilding, circa 1988; and five years ago this week, respectively.

2 Can’t see the loop? It’s inside the tower. A clever bit of design conceals the inversion from outside the ride; also the track later re-enters the fort (on the left of the photo) to “thread the needle” through the centre of the loop. When they were running three trains (two in motion at once) at the proper cadence, it was quite impressive as you’d loop around while a second train went through the middle, and then go through the middle while a third train did the loop!

3 I’m told that the “tower” caught fire during disassembly and was destroyed.

Even More 1999!

Spencer’s filter

Last month I implemented an alternative mode to view this website “like it’s 1999”, complete with with cursor trails, 88×31 buttons, tables for layout1, tiled backgrounds, and even a (fake) hit counter.

One thing I’d have liked to do for 1999 Mode but didn’t get around to would have been to make the images look like it was the 90s, too.

Back then, many Web users only had graphics hardware capable of displaying 256 distinct colours. Across different platforms and operating systems, they weren’t even necessarily the same 256 colours2! But the early Web agreed on a 216-colour palette that all those 8-bit systems could at least approximate pretty well.

I had an idea that I could make my images look “216-colour”-ish by using CSS to apply an SVG filter, but didn’t implement it.

But Spencer, a long-running source of excellent blog comments, stepped up and wrote an SVG filter for me! I’ve tweaked 1999 Mode already to use it… and I’ve just got to say it’s excellent: huge thanks, Spencer!

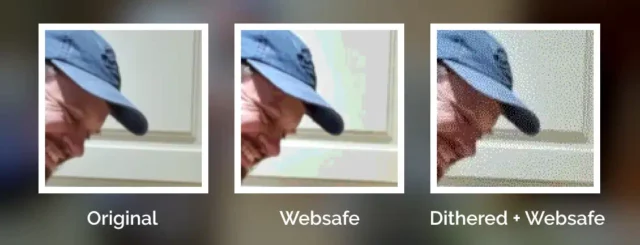

The filter coerces colours to their nearest colour in the “Web safe” palette, resulting in things like this:

Plenty of pictures genuinely looked like that on the Web of the 1990s, especially if you happened to be using a computer only capable of 8-bit colour to view a page built by somebody who hadn’t realised that not everybody would experience 24-bit colour like they did3.

Dithering

But not all images in the “Web safe” palette looked like this, because savvy web developers knew to dither their images when converting them to a limited palette. Let’s have another go:

Dithering introduces random noise to media4 in order to reduce the likelihood that a “block” will all be rounded to the same value. Instead; in our picture, a block of what would otherwise be the same colour ends up being rounded to maybe half a dozen different colours, clustered together such that the ratio in a given part of the picture is, on average, a better approximation of the correct colour.

The result is analogous to how halftone printing – the aesthetic of old comics and newspapers, with different-sized dots made from few colours of ink – produces the illusion of a continuous gradient of colour so long as you look at it from far-enough away.

The other year I read a spectacular article by Surma that explained in a very-approachable way how and why different dithering algorithms produce the results they do. If you’ve any interest whatsoever in a deep dive or just want to know what blue noise is and why you should care, I’d highly recommend it.

You used to see digital dithering everywhere, but nowadays it’s so rare that it leaps out as a revolutionary aesthetic when, for example, it gets used in a video game.

All of which is to say that: I really appreciate Spencer’s work to make my “1999 Mode” impose a 216-colour palette on images. But while it’s closer to the truth, it still doesn’t quite reflect what my website would’ve looked like in the 1990s because I made extensive use of dithering when I saved my images in Web safe palettes5.

Why did I take the time to dither my images, back in the day? Because doing the hard work once, as a creator of graphical Web pages, saves time and computation (and can look better!), compared to making every single Web visitor’s browser do it every single time.

Which, now I think about it, is a lesson that’s still true today (I’m talking to you, developers who send a tonne of JavaScript and ask my browser to generate the HTML for you rather than just sending me the HTML in the first place!).

Footnotes

1 Actually, my “1999 mode” doesn’t use tables for layout; it pretty much only applies a CSS overlay, but it’s deliberately designed to look a lot like my blog did in 1999, which did use tables for layout. For those too young to remember: back before CSS gave us the ability to lay out content in diverse ways, it was commonplace to use a table – often with the borders and cell-padding reduced to zero – to achieve things that today would be simple, like putting a menu down the edge of a page or an image alongside some text content. Using tables for non-tabular data causes problems, though: not only is it hard to make a usable responsive website with them, it also reduces the control you have over the order of the content, which upsets some kinds of accessibility technologies. Oh, and it’s semantically-invalid, of course, to describe something as a table if it’s not.

2 Perhaps as few as 22 colours were defined the same across all widespread colour-capable Web systems. At first that sounds bad. Then you remember that 4-bit (16 colour) palettes used to look look perfectly fine in 90s videogames. But then you realise that the specific 22 “very safe” colours are pretty shit and useless for rendering anything that isn’t composed of black, white, bright red, and maybe one of a few greeny-yellows. Ugh. For your amusement, here’s a copy of the image rendered using only the “very safe” 22 colours.

3 Spencer’s SVG filter does pretty-much the same thing as a computer might if asked to render a 24-bit colour image using only 8-bit colour. Simply “rounding” each pixel’s colour to the nearest available colour is a fast operation, even on older hardware and with larger images.

4 Note that I didn’t say “images”: dithering is also used to produce the same “more natural” feel for audio, too, when reducing its bitrate (i.e. reducing the number of finite states into which the waveform can be quantised for digitisation), for example.

5 I’m aware that my footnotes are capable of nerdsniping Spencer, so by writing this there’s a risk that he’ll, y’know, find a way to express a dithering algorithm as an SVG filter too. Which I suspect isn’t possible, but who knows! 😅

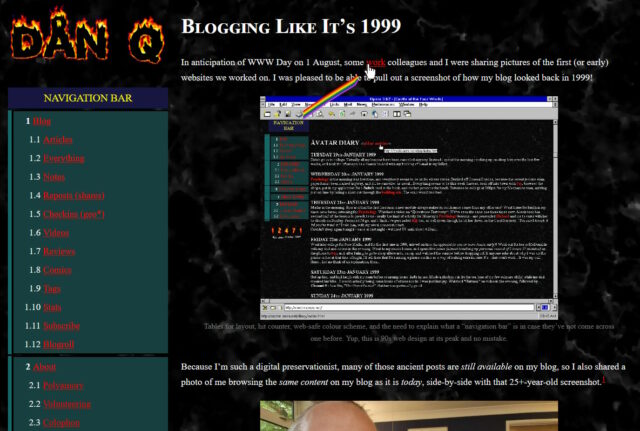

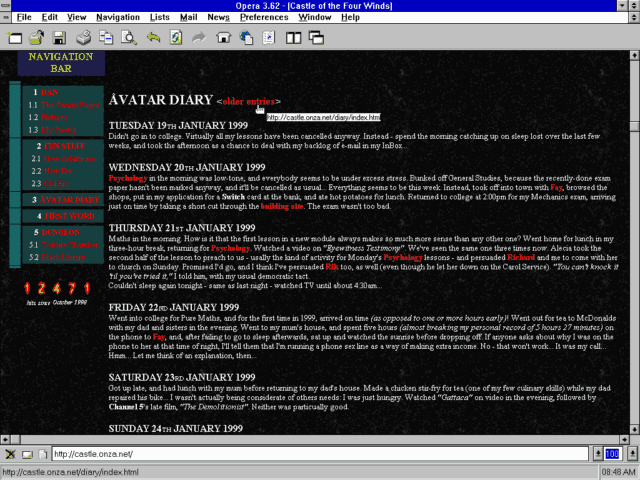

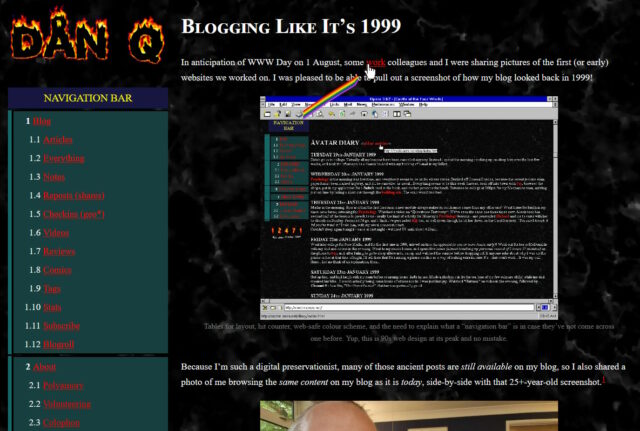

Blogging Like It’s 1999

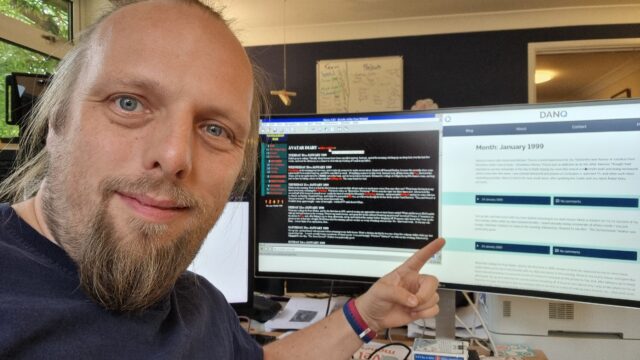

In anticipation of WWW Day on 1 August, some work colleagues and I were sharing pictures of the first (or early) websites we worked on. I was pleased to be able to pull out a screenshot of how my blog looked back in 1999!

Because I’m such a digital preservationist, many of those ancient posts are still available on my blog, so I also shared a photo of me browsing the same content on my blog as it is today, side-by-side with that 25+-year-old screenshot.1

Update: This photo eventually appeared on a LinkedIn post on Automattic’s profile.

This inspired me to make a toggleable “alternate theme” for my blog: 1999 Mode.

Switch to it, and you’ll see a modern reinterpretation of my late-1990s blog theme, featuring:

- A “table-like” layout.2

- White text on a black marbled “seamless texture” background, just like you’d expect on any GeoCities page.

- Pre-rendered fire text3, including – of course – animated GIFs.4

- A (fake) hit counter.

- A stack of 88×31 micro-banners, as was all the rage at the time. (And seem to be making a comeback in IndieWeb circles…)

- Cursor trails (with thanks to Tim Holman)!

- I’ve even applied

img { image-rendering: crisp-edges; }to try to compensate for modern browsers’ capability for subpixel rendering when rescaling images: let them eat pixels!5

I’ve added 1999 Mode to my April Fools gags so, like this year, if you happen to visit my site on or around 1 April, there’s a change you’ll see it in 1999 mode anyway. What fun!

I think there’s a possible future blog post about Web design challenges of the 1990s. Things like: what it the user agent doesn’t support images? What if it supports GIFs, but not animated ones (some browsers would just show the first frame, so you’d want to choose your first frame appropriately)? How do I ensure that people see the right content if they skip my frameset? Which browser-specific features can I safely use, and where do I need a fallback6? Will this work well on all resolutions down to 640×480 (minus browser chrome)? And so on.

Any interest in that particular rabbit hole of digital history?

Footnotes

1 Some of the addresses have changed, but from Summer 2003 onwards I’ve had a solid chain of redirects in place to try to keep content available via whatever address it was at. Because Cool URIs Don’t Change. This occasionally turns out to be useful!

2 Actually, the entire theme is just a CSS change, so no tables are added. But I’ve tried to make it look like I’m using tables for layout, because that (and spacer GIFs) were all we had back in the day.

3 Obviously the title saying “Dan Q” is modern, because that wasn’t even my name back then, but this is more a reimagining of how my site would have looked if I were transported back to 1999 and made to do it all again.

4 I was slightly obsessed for a couple of years in the late 90s with flaming text on black marble backgrounds. The hit counter in my screenshot above – with numbers on fire – was one I made, not a third-party one; and because mine was the only one of my friends’ hosts that would let me run CGIs, my Perl script powered the hit counters for most of my friends’ sites too.

5 I considered, but couldn’t be bothered, implementing an SVG CSS filter: to posterize my images down to 8-bit colour, for that real

“I’m on an old graphics card” feel! If anybody’s already implemented such a thing under a license that I can use, let me know and I’ll integrate it!

6 And what about those times where using a fallback might make things worse, like

how Netscape 7 made the <blink><marquee> combination unbearable!

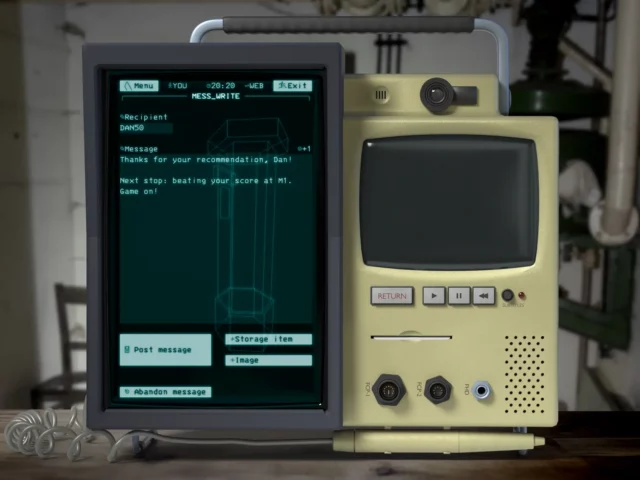

ARCC

In the late ’70s, a shadowy group of British technologists concluded that nuclear war was inevitable and secretly started work on a cutting-edge system designed to help rebuild society. And thanks to Matt Round-and-friends at vole.wtf (who I might have mentioned before), the system they created – ARCC – can now be emulated in your browser.

I’ve been playing with it on-and-off all year, and I’ve (finally) managed to finish exploring pretty-much everything the platform currently has to offer, which makes it pretty damn good value for money for the £6.52 I paid for my ticket (the price started at £2.56 and increases by 2p for every ticket sold). But you can get it cheaper than I did if you score 25+ on one of the emulated games.

Most of what I just told you is true. Everything… except the premise. There never was a secretive cabal of engineers who made this whackballs computer system. What vole.wtf emulates is an imaginary system, and playing with that system is like stepping into a bizarre alternate timeline or a weird world. Over several separate days of visits you’ll explore more and more of a beautifully-realised fiction that draws from retrocomputing, Cold War fearmongering, early multi-user networks with dumb terminal interfaces, and aesthetics that straddle the tripoint between VHS, Teletext, and BBS systems. Oh yeah, and it’s also a lot like being in a cult.

Needless to say, therefore, it presses all the right buttons for me.

DAN50.

If you enjoy any of those things, maybe you’d like this too. I can’t begin to explain the amount of work that’s gone into it. If you’re looking for anything more-specific in a recommendation, suffice to say: this is a piece of art worth seeing.

Framing Device

Doors

As our house rennovations/attic conversions come to a close, I found myself up in what will soon become my en suite, fitting a mirror, towel rail, and other accessories.

Wanting to minimise how much my power tool usage disturbed the rest of the house, I went to close the door separating my new bedroom from my rest of my house, only to find that it didn’t properly fit its frame and instead jammed part-way-closed.

Somehow we’d never tested that this door closed properly before we paid the final instalment to the fitters. And while I’m sure they’d have come back to repair the problem if I asked, I figured that it’d be faster and more-satisfying to fix it for myself.

Homes

As a result of an extension – constructed long before we moved in – the house in Preston in which spent much of my childhood had not just a front and a back door but what we called the “side door”, which connected the kitchen to the driveway.

Unfortunately the door that was installed as the “side door” was really designed for interior use and it suffered for every winter it faced the biting wet North wind.

My father’s DIY skills could be rated as somewhere between mediocre and catastrophic, but his desire to not spend money “frivolously” was strong, and so he never repaired nor replaced the troublesome door. Over the course of each year the wood would invariably absorb more and more water and swell until it became stiff and hard to open and close.

The solution: every time my grandfather would visit us, each Christmas, my dad would have his dad take down the door, plane an eighth of an inch or so off the bottom, and re-hang it.

Sometimes, as a child, I’d help him do so.

Planes

The first thing to do when repairing a badly-fitting door is work out exactly where it’s sticking. I borrowed a wax crayon from the kids’ art supplies, coloured the edge of the door, and opened and closed it a few times (as far as possible) to spot where the marks had smudged.

Fortunately my new bedroom door was only sticking along the top edge, so I could get by without unmounting it so long as I could brace it in place. I lugged a heavy fence post rammer from the garage and used it to brace the door in place, then climbed a stepladder to comfortably reach the top.

Loss

After my paternal grandfather died, there was nobody left who would attend to the side door of our house. Each year, it became a little stiffer, until one day it wouldn’t open at all.

Surely this would be the point at which he’d pry open his wallet and pay for it to be replaced?

Nope. Instead, he inexpertly screwed a skirting board to it and declared that it was now no-longer a door, but a wall.

I suppose from a functionalist perspective he was correct, but it still takes a special level of boldness to simply say “That door? It’s a wall now.”

Sand

Of all the important tasks a carpenter (or in this case, DIY-er) must undertake, hand sanding must surely be the least-satisfying.

But reaching the end of the process, the feel of a freshly-planed, carefully-sanded piece of wood is fantastic. This surface represented chaos, and now it represents order. Order that you yourself have brought about.

Often, you’ll be the only one to know. When my grandfather would plane and sand the bottom edge of our house’s side door, he’d give it a treatment of oil (in a doomed-to-fail attempt to keep the moisture out) and then hang it again. Nobody can see its underside once it’s hung, and so his handiwork was invisible to anybody who hadn’t spent the last couple of months swearing at the stiffness of the door.

Even though the top of my door is visible – particularly visible, given its sloping face – nobody sees the result of the sanding because it’s hidden beneath a layer of paint.

A few brush strokes provide the final touch to a spot of DIY… that in provided a framing device for me to share a moment of nostalgia with you.

Sweep away the wood shavings. Keep the memories.

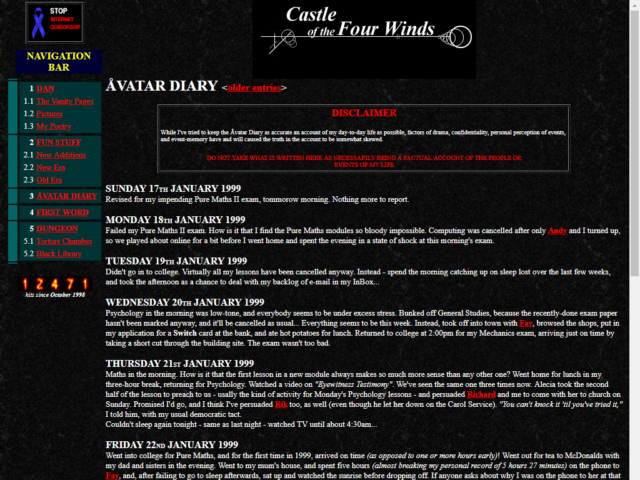

Blog to 5K

This is my 5,000th post on this blog.

Okay, we’re gonna need a whole lot of caveats on the “this is 5,000” claim:

Engage pedantry mode

First, there’s a Ship of Theseus consideration. By “this blog”, I’m referring to what I feel is a continuation (with short breaks) of my personal diary-style writing online from the original “Avatar Diary” on castle.onza.net in the 1990s via “Dan’s Pages” on avangel.com in the 2000s through the relaunch on scatmania.org in 2003 through migrating to danq.me in 2012. If you feel that a change of domain precludes continuation, you might disagree with me. Although you’d be a fool to do so: clearly a blog can change its domain and still be the same blog, right? Back in 2018 I celebrated the 20th anniversary of my first blog post by revisiting how my blog had looked, felt, and changed over the decades, if you’re looking for further reading.

In late 1999 I ran “Cool Thing of the Day (to do at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth)” as a way of staying connected to my friends back in Preston as we all went our separate ways to study. Initially sent out by email, I later maintained a web page with a log of the entries I’d sent out, but the address wasn’t publicly-circulated. I consider this to be a continuation of the Avatar Diary before it and the predecessor to Dan’s Pages on avangel.com after it, but a pedant might argue that because the content wasn’t born as a blog post, perhaps it’s invalid.

Pedants might also bring up the issue of contemporaneity. In 2004 a server fault resulted in the loss of a significant number of 149 blog posts, of which only 85 have been fully-recovered. Some were resurrected from backups as late as 2012, and some didn’t recover their lost images until later still – this one had some content recovered as late as 2017! If you consider the absence of a pre-2004 post until 2012 a sequence-breaker, that’s an issue. It’s theoretically possible, of course, that other old posts might be recovered and injected, and this post might before the 5,001st, 5,002nd, or later post, in terms of chronological post-date. Who knows!

Then there’s the posts injected retroactively. I’ve written software that, since 2018, has ensured that my geocaching logs get syndicated via my blog when I publish them to one of the other logging sites I use, and I retroactively imported all of my previous logs. These never appeared on my blog when they were written: should they count? What about more egregious examples of necroposting, like this post dated long before I ever touched a keyboard? I’m counting them all.

I’m also counting other kinds of less-public content too. Did you know that I sometimes make posts that don’t appear on my front page, and you have to subscribe e.g. by RSS to get them? They have web addresses – although search engines are discouraged from indexing them – and people find them with or without subscribing. Maybe you should subscribe if you haven’t already?

Note that I’m not counting my comments on my own blog, even though many of them are very long, like this 2,700-word exploration of a jigsaw puzzle geocache, or this 1,000-word analogy for cookie theft via cross-site scripting. I’d like to think that for any post that you’d prefer to rule out, given the issues already described, you’d find a comment that could justifiably have been a post in its own right.[/footnote]

Back to celebration mode

Generating a chart...

If this message doesn't go away, the JavaScript that makes this magic work probably isn't doing its job right: please tell Dan so he can fix it.

Generating a chart...

If this message doesn't go away, the JavaScript that makes this magic work probably isn't doing its job right: please tell Dan so he can fix it.

Let’s take a look at some of those previous milestone posts:

- In post 1,000 I announced that I was ready for 2005’s NaNoWriMo. I had a big ol’ argument in the comments with Statto about the value of the exercise. It’s possible that I ultimately wrote more words arguing with him than I did on my writing project that month.

- Post 2,000, in 2012, saw me attend the coroner’s inquest into my father’s death. Kate, one of his partners, had appeared as a “surprise witness”, seemingly mostly because she wanted one last “I told you so” about the condition of my dad’s walking boots.

- I reposted a link to a Perry Bible Fellowship comic for post 3,000, in 2017. For webcomics that update irregularly and infrequently, like PBF and Bird & Moon,3 I’m glad that I’m an avid feed user so I get to hear about these things as-they-happen, but I appreciated that others might not, hence the repost.

- I was in and around San Francisco in August 2019, and post 4,000 was me finding a geocache. The same geocaching expedition saw me discover (and vlog about) a favourite geocache.

I absolutely count this as the 5,000th post on this blog.

Footnotes

1 Don’t go look at them. Just don’t. I was a teenager.

2 Via a bit of POSSE and a bit of PESOS I do a lot of crossposting (the diagram in that post is a little out-of-date now, though).

3 Bird & Moon, of course, doesn’t have a subscription feed that I’m aware of, but FreshRSS‘s “killer feature” of XPath scraping makes the same kind of thing possible.

If you’ve ever found yourself missing the “good old days” of the web, what is it that you miss?

This is a reply to a post published elsewhere. Its content might be duplicated as a traditional comment at the original source.

This. You wanted to identify a song? Type some of the lyrics into a search engine and hope that somebody transcribed the same lyrics onto their fansite. You needed to know a fact? Better hope some guru had taken the time to share it, or it’d be time for a trip to the library

Not having information instantly easy to find meant that you really treasured your online discoveries. You’d bookmark the best sites on whatever topics you cared about and feel no awkwardness about emailing a fellow netizen (or signing their guestbook to tell them) about a resource they might like. And then you’d check back, manually, from time to time to see what was new.

The young Web was still magical and powerful, but the effort to payoff ratio was harder, and that made you appreciate your own and other people’s efforts more.

Aberystwyth 1984

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This promotional video for Aberystwyth University has been kindly archived onto YouTube by one of the undergraduate students who features in it. It was produced in 1984; approximately the same time I first visited Aberystwyth, although it would take until fifteen years later in 1999 for me to become a student there myself.

But the thing is… this 1984 video, shot on VHS in 1984, could absolutely be mistaken at-a-glance for a video shot on an early digital video camera a decade and a half later. The pace of change in Aberystwyth was and is glacial; somehow even the fashion and music seen in Pier Pressure in the video could pass for late-90s!

Anyway: I found the entire video amazingly nostalgic in spite of how far it predates my attendance of the University! Amazing.