A recent article by Janelle Shane talked about her recent experience with Microsoft Azure’s image processing API. If you’ve not come across her work before, I recommend starting with her candy hearts, or else new My Little Pony characters, invented by a computer. Anyway:

The Azure image processing API is a software tool powered by a neural net, a type of artificial intelligence that attempts to replicate a particular model of how (we believe) brains to work: connecting inputs (in this case, pixels of an image) to the entry nodes of a large, self-modifying network and reading the output, “retraining” the network based on feedback from the quality of the output it produces. Neural nets have loads of practical uses and even more theoretical ones, but Janelle’s article was about how confused the AI got when shown certain pictures containing (or not containing!) sheep.

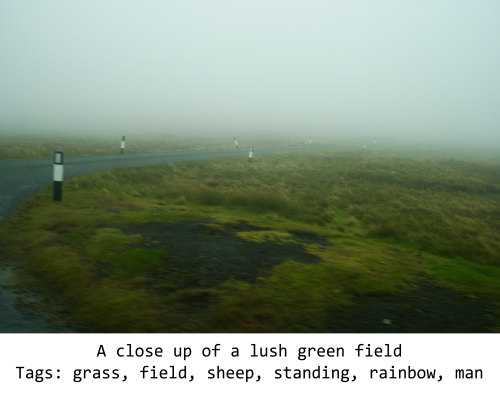

The AI had clearly been trained with lots of pictures that contained green, foggy, rural hillsides and sheep, and had come to associate the two. Remember that all the machine is doing is learning to associate keywords with particular features, and it’s clearly been shown many pictures that “look like” this that do contain sheep, and so it’s come to learn that “sheep” is one of the words that you use when you see a scene like this. Janelle took to Twitter to ask for pictures of sheep in unusual places, and the Internet obliged.

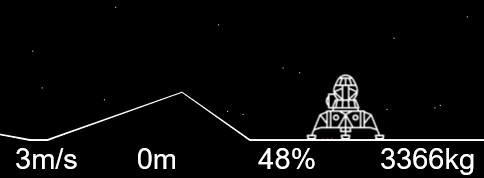

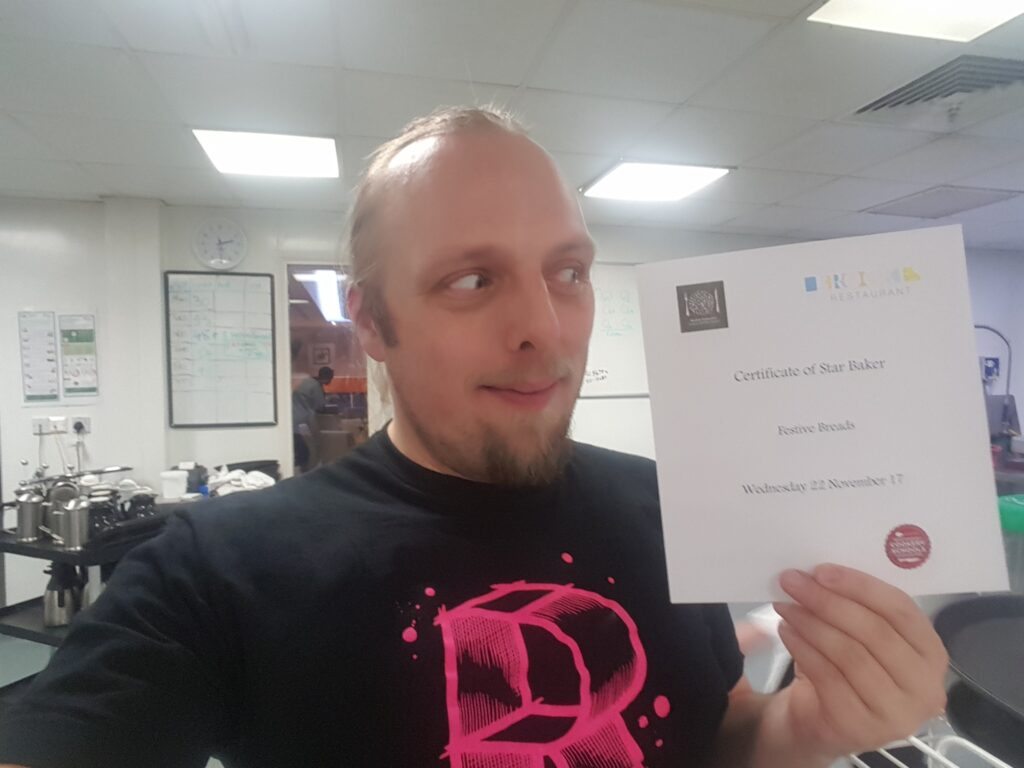

Many of the experiments resulting from this – such as the one shown above – work well to demonstrate this hyper-focus on context: a sheep up a tree is a bird, a sheep on a lead is a dog, a sheep painted orange is a flower, and so on. And while we laugh at them, there’s something about them that’s actually pretty… “human”.

I say this because I’ve observed similar quirks in the way that small children pick up language, too (conveniently, I’ve got a pair of readily-available subjects, aged 4 and 1, for my experiments in language acquisition…). You’ve probably seen it yourself: a toddler whose “training set” of data has principally included a suburban landscape describing the first cow they see as a “dog”. Or when they use a new word or phrase they’ve learned in a way that makes no sense in the current context, like when our eldest interrupted dinner to say, in the most-polite voice imaginable, “for God’s sake would somebody give me some water please”. And just the other day, the youngest waved goodbye to an empty room, presumably because it’s one that he often leaves on his way up to bed

For all we joke, this similarity between the ways in which artificial neural nets and small humans learn language is perhaps the most-accessible evidence that neural nets are a strong (if imperfect) model for how brains actually work! The major differences between the two might be simply that:

- Our artificial neural nets are significantly smaller and less-sophisticated than most biological ones.

- Biological neural nets (brains) benefit from continuous varied stimuli from an enormous number of sensory inputs, and will even self-stimulate (via, for example, dreaming) – although the latter is something with which AI researchers sometimes experiment.

Things we take as fundamental, such as the nouns we assign to the objects in our world, are actually social/intellectual constructs. Our minds are powerful general-purpose computers, but they’re built on top of a biology with far simpler concerns: about what is and is-not part of our family or tribe, about what’s delicious to eat, about which animals are friendly and which are dangerous, and so on. Insofar as artificial neural nets are an effective model of human learning, the way they react to “pranks” like these might reveal underlying truths about how we perceive the world.

And maybe somewhere, an android really is dreaming of an electric sheep… only it’s actually an electric cat.