(Just want the instructions? Scroll down.)

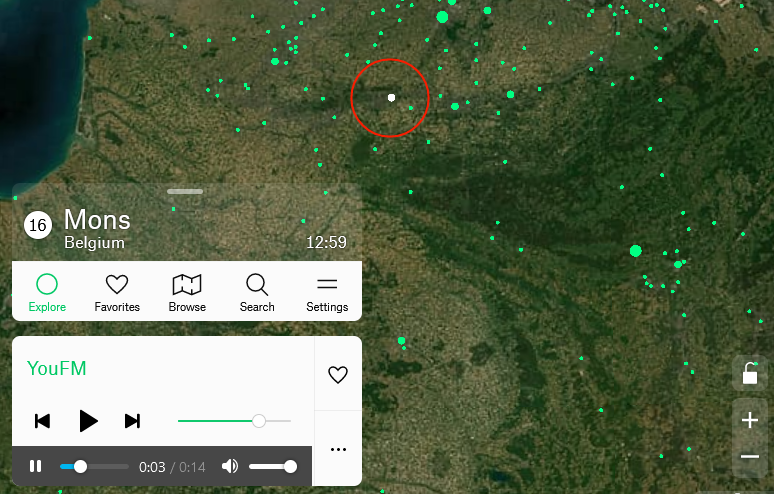

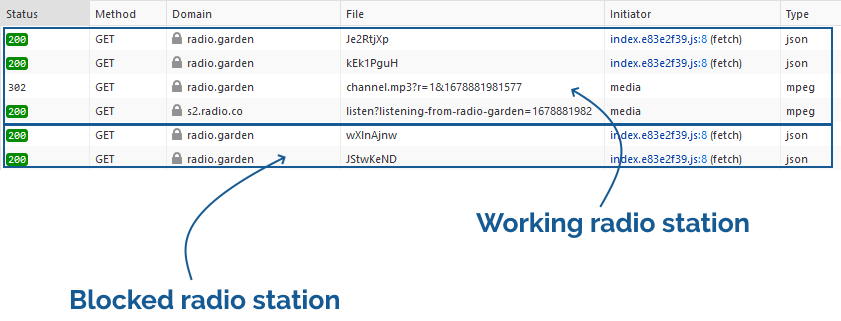

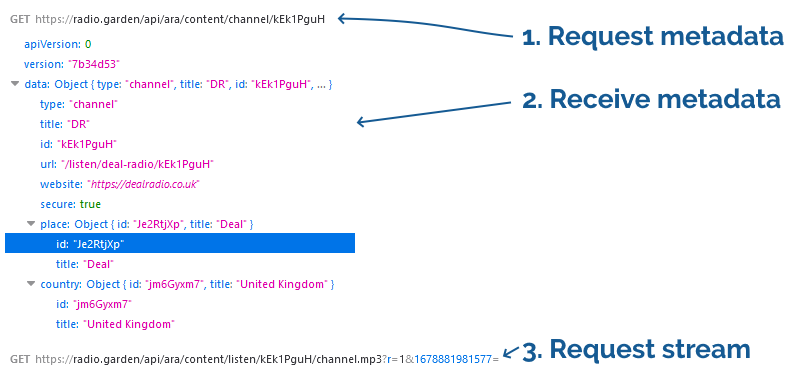

A year and a half ago I came up with a technique for intercepting the “shuffle” operation on jigsaw website Jigidi, allowing players to force the pieces to appear in a consecutive “stack” for ludicrously easy solving. I did this partially because I was annoyed that a collection of geocaches near me used Jigidi puzzles as a barrier to their coordinates1… but also because I enjoy hacking my way around artificially-imposed constraints on the Web (see, for example, my efforts last week to circumvent region-blocking on radio.garden).

My solver didn’t work for long: code changes at Jigidi’s end first made it harder, then made it impossible, to use the approach I suggested. That’s fine by me – I’d already got what I wanted – but the comments thread on that post suggests that there’s a lot of people who wish it still worked!2 And so I ignored the pleas of people who wanted me to re-develop a “Jigidi solver”. Until recently, when I once again needed to solve a jigsaw puzzle in order to find a geocache’s coordinates.

Making A Jigidi Helper

Rather than interfere with the code provided by Jigidi, I decided to take a more-abstract approach: swapping out the jigsaw’s image for one that would be easier.

This approach benefits from (a) having multiple mechanisms of application: query interception, DNS hijacking, etc., meaning that if one stops working then another one can be easily rolled-out, and (b) not relying so-heavily on the structure of Jigidi’s code (and therefore not being likely to “break” as a result of future upgrades to Jigidi’s platform).

Watch a video demonstrating the approach:

It’s not as powerful as my previous technique – more a “helper” than a “solver” – but it’s good enough to shave at least half the time off that I’d otherwise spend solving a Jigidi jigsaw, which means I get to spend more time out in the rain looking for lost tupperware. (If only geocaching were even the weirdest of my hobbies…)

How To Use The Jigidi Helper

To do this yourself and simplify your efforts to solve those annoying “all one colour” or otherwise super-frustrating jigsaw puzzles, here’s what you do:

- Visit a Jigidi jigsaw. Do not be logged-in to a Jigidi account.

- Copy my JavaScript code into your clipboard.

- Open your browser’s debug tools (usually F12). In the Console tab, paste it and press enter. You can close your debug tools again (F12) if you like.

- Press Jigidi’s “restart” button, next to the timer. The jigsaw will restart, but the picture will be replaced with one that’s easier-to-solve than most, as described below.

- Once you solve the jigsaw, the image will revert to normal (turn your screen around and show off your success to a friend!).

What makes it easier to solve?

The replacement image has the following characteristics that make it easier to solve than it might otherwise be:

- Every piece has written on it the row and column it belongs in.

- Every “column” is striped in a different colour.

- Striped “bands” run along entire rows and columns.

To solve the jigsaw, start by grouping colours together, then start combining those that belong in the same column (based on the second digit on the piece). Join whole or partial columns together as you go.

I’ve been using this technique or related ones for over six months now and no code changes on Jigidi’s side have impacted upon it at all, so it’s probably got better longevity than the previous approach. I’m not entirely happy with it, and you might not be either, so feel free to fork my code and improve it: the legiblity of the numbers is sometimes suboptimal, and the colour banding repeats on larger jigsaws which I’d rather avoid. There’s probably also potential to improve colour-recognition by making the colour bands span the gaps between rows or columns of pieces, too, but more experiments are needed and, frankly, I’m not the right person for the job. For the second time, I’m going to abandon a tool that streamlines Jigidi solving because I’ve already gotten what I needed out of it, and I’ll leave it up to you if you want to come up with an improvement and share it with the community.

Footnotes

1 As I’ve mentioned before, and still nobody believes me: I’m not a fan of jigsaws! If you enjoy them, that’s great: grab a bucket of popcorn and a jigsaw and go wild… but don’t feel compelled to share either with me.

2 The comments also include asuper-helpful person called Rich who’s been manually solving people’s puzzles for them, and somebody called Perdita who “could be my grandmother” (except: no) with whom I enjoyed a conversation on- and off-line about the ethics of my technique. It’s one of the most-popular comment threads my blog has ever seen.