Kicking off day #1 of my three-month sabbatical from work at a hotel in Reading, at a meeting with fellow Three Rings volunteers to discuss our organisational culture and values.

Tag: volunteering

Sick words

This evening I pushed against my illness-addled brain to try to sit in on the fortnightly Zoom call with the Three Rings dev team. Unfortunately it seems like the primary symptom of my cold is an inability to string words together.

At one point, I apologised to by colleague “Beff” (I meant “Bev”, but I had just been talking about “Geoff”) that I couldn’t work out how to stop “scaring my screen” (well, I suppose Halloween is coming up…). Then, realising my mistake, explained that it was a bit of a “ting-twister”.

I should just go to bed, right?

Note #24388

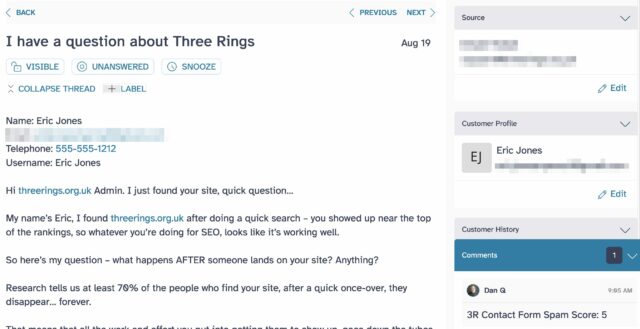

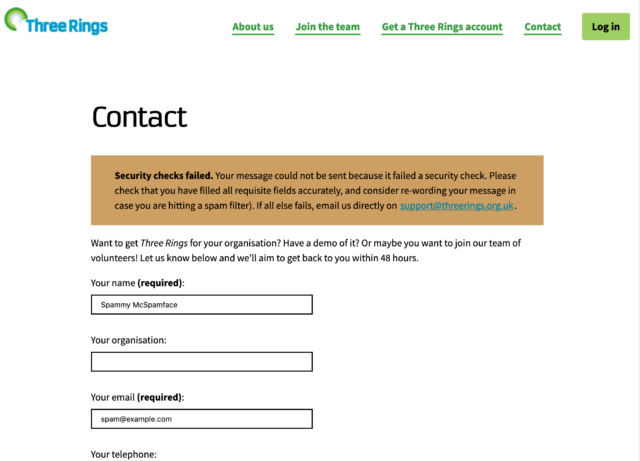

Roll Your Own Antispam

Three Rings operates a Web contact form to help people get in touch with us: the idea is that it provides a quick and easy way to reach out if you’re a charity who might be able to make use of the system, a user who’s having difficulty with the features of the software, or maybe a potential new volunteer willing to give your time to the project.

But then the volume of spam it received increased dramatically. We don’t want our support team volunteers to spend all their time categorising spam: even if it doesn’t take long, it’s demoralising. So what could we do?

Our conventional antispam tools are configured pretty liberally: we don’t want to reject a contact from a legitimate user just because their message hits lots of scammy keywords (e.g. if a user’s having difficulty logging in and has copy-pasted all of the error messages they received, that can look a lot like a password reset spoofing scam to a spam filter). And we don’t want to add a CAPTCHA, because not only do those create a barrier to humans – while not necessarily reducing spam very much, nowadays – they’re often terrible for accessibility, privacy, or both.

But it didn’t take much analysis to spot some patterns unique to our contact form and the questions it asks that might provide an opportunity. For example, we discovered that spam messages would more-often-than-average:

- Fill in both the “name” and (optional) “Three Rings username” field with the same value. While it’s cetainly possible for Three Rings users to have a login username that’s identical to their name, it’s very rare. But automated form-fillers seem to disproportionately pair-up these two fields.

- Fill the phone number field with a known-fake phone number or a non-internationalised phone number from a country in which we currently support no charities. Legitimate non-UK contacts tend to put international-format phone numbers into this optional field, if they fill it at all. Spammers often put NANP (North American Numbering Plan) numbers.

- Include many links in the body of the message. A few links, especially if they’re to our services (e.g. when people are asking for help) is not-uncommon in legitimate messages. Many links, few of which point to our servers, almost certainly means spam.

- Choose the first option for the choose -one question “how can we help you?” Of course real humans sometimes pick this option too, but spammers almost always choose it.

None of these characteristics alone, or any of the half dozen or so others we analysed (including invisible checks like honeypots and IP-based geofencing), are reason to suspect a message of being spam. But taken together, they’re almost a sure thing.

To begin with, we assigned scores to each characteristic and automated the tagging of messages in our ticketing system with these scores. At this point, we didn’t do anything to block such messages: we were just collecting data. Over time, this allowed us to find a safe “threshold” score above which a message was certainly spam.

Once we’d found our threshold we were able to engage a soft-block of submissions that exceeded it, and immediately the volume of spam making it to the ticketing system dropped considerably. Under 70 lines of PHP code (which sadly I can’t share with you) and we reduced our spam rate by over 80% while having, as far as we can see, no impact on the false-positive rate.

Where conventional antispam solutions weren’t quite cutting it, implementing a few rules specific to our particular use-case made all the difference. Sometimes you’ve just got to roll your sleeves up and look at the actual data you do/don’t want, and adapt your filters accordingly.

[Bloganuary] Not The Lottery

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What would you do if you won the lottery?

I know what I’d do, and I’ll get to that. But first, let me tell you about the lottery game I play.

Not the lottery

I don’t generally play the lottery1. I’ve made interactive widgets (now broken) to illustrate quite how many losers there are in these games and hopefully help highlight that while “it could be you”… it won’t be.

But if I ever happen to be somewhere that the lottery results are being announced, I sometimes like to play a game I call Not The Lottery.2 Here’s how you play:

- Set aside the money it would have cost for a ticket.

- Think of the numbers you’d have played.

- When those numbers don’t come up, congratulations: you just won not-wasting-your-money!3

Want to play Not The Lottery retroactively? Cool. I’ve made and open-sourced a tool for that. Hopefully it’ll load below and you can choose some numbers (or take a Lucky Dip) and have it played through the entirety of EuroMillions history and see how much money you’d have won if you’d only played them every week. Or, to look at things from a brighter perspective, how much you’ve saved by not playing. It’s almost-certainly in the thousands.

Winning the lottery

But that’s not what the question’s really about, is it? We don’t ask people “what would they do if they won the lottery?” because we think it’s likely to happen4 We ask them because… well, because it’s fun to fantasise.

And I sort-of gave the answer away on day 20 of Bloganuary: I’d do my “dream job”. I’d work (for free) for Three Rings, like I already do, except instead of spending a couple of hours a week on it on average I’d spend about ten times that. I’d use the luxury of not having to work to focus on things that I know I can do to make the world a better place.

Sure, there’s other things I’d do. They’re mostly obvious things that I’d hope anybody in my position would do. Pay off the mortgage (and for all the works currently being done to

infuriate the dog improve the house). Arrange some kind of slow-access trust or annuity for the people closest to me so that

they need not worry about money, nor about having to work out how to spend, save, or invest a lump sum. Maybe a holiday or two. Certainly some charitable donations. Perhaps buy

really expensive ketchup: the finest dijon ketchup5.

But mostly I’d just want to be able to live as comfortably as I do now, or perhaps slightly more, and spend a greater proportion of my time than I already do making charities work better.

I don’t know if that makes me insufferably self-righteous or insufferably simple-minded, but it’s probably one of those.

Footnotes

1 I’ve been caught describing it as “a tax on people who are bad at maths”, but I don’t truly believe that (although I am concerned about how readily we let people get addicted to problematic gambling and then keep encouraging them to play with dark patterns that hide how low the odds truly are). I’ve even been known to buy a ticket or two, some years.

2 While writing this, I decided to retroactively play for last Friday, having not seen whatever numbers came up. I guessed only one of them. Hurrah! That means I saved £2.50 by not playing!

3 There are, of course, other possible outcomes. You could have missed out on winning a small prize – the odds aren’t that low – but the solution to this is simple: just keep playing Not The Lottery and you, as the “house”, will come out on top in the end. Alternatively, it’s just-about possible that you could pluck the jackpot numbers from thin air, in which case: well done! You’re doing better than Derren Brown when in 2009 he performed a pretty good magic trick but then turned it into a turd when he “explained” it using pseudoscience (why not just stick with “I’m a magician, duh”; when you play the Uri Geller card you just make yourself look like an idiot). Let’s find a way to use those superpowers for good. Because what you’ve got is a superpower. For context: if you played Not The Lottery twice a week, every week, without fail, for 393 years… you’d still only have a 1% chance of having ever predicted a jackpot in your five-lifetimes.

4 What if we lived in a world where we did use statistics to think about the hypothetical questions we ask people? Would we ask “what would you do if you were stuck by lightning?”, given that the lifetime chance of being killed by lightning is significantly greater than the chance of winning the jackpot, even if you play every draw!

5 Y’know, to keep in the fridge in the treehouse.

[Bloganuary] Dream Job

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What’s your dream job?

It feels like a bit of a cop-out to say I’m already doing it, but that’s true. Well, mostly (read on and I’ll make a counterpoint!).

Automattic

I’m incredibly fortunate that my job gets to tick so many of the boxes I’d put on a “dream job wishlist”:

- I work on things that really matter. Automattic’s products make Web publishing and eCommerce available to the world without “lock-in” or proprietary bullshit. I genuinely believe that Automattic’s work helps to democratise the Internet and acts, in a small way, as a counterbalance to the dominance of the big social media silos.

- I get to make the world a better place by giving away as much intellectual property as possible. Automattic’s internal policy is basically “you don’t have to ask to open source something; give away anything you like so long as it’s not the passwords”.1 Open Source is one of the most powerful ideas of our generation, and all that.

- We work in a distributed, asynchronous way. I work from where I want, when I want. I’m given the autonomy to understand what my ideal working environment is and make the most of it. Some mornings I’m just not feeling that coding flow, so I cycle somewhere different and try working the afternoon in a different location. Some weekends I’m struck by inspiration and fire up my work laptop to make the most of it, because, y’know, I’m working on things that really matter and I care about them.

- I work with amazing people who I learn from and inspire me. Automattic’s home to some incredibly talented people and I love that I’ve managed to find a place that actively pushes me to study new things every day.

- Automattic’s commitment to diversity & inclusion is very good-to-excellent. As well as getting work work alongside people from a hundred different countries and with amazingly different backgrounds, I love that I get to work in one of the queerest and most queer-affirming environments I’ve ever been paid to be in.

Did I mention that we’re hiring?2

Three Rings

But you know where else ticks all of those boxes? My voluntary work with Three Rings. Let me talk you through that wishlist again:

- I work on things that really matter. We produce the longest-running volunteer management system in the world3 We produce it as volunteers ourselves, because we believe that volunteering matters and we want to make it as easy as possible for as many people as possible to do as much good as possible, and this allows us to give it away as cheaply as possible: for free, to the smallest and poorest charities.

- I get to make the world a better place by facilitating the work of suicide helplines, citizens advice bureaus, child support services, environmental charities, community libraries and similar enterprises, museums, theatres, charity fundraisers, and so many more good works. Back when I used to to helpline volunteering I might do a three hour shift and help one or two people, and I was… okay at it. Now I get to spend those three hours making tools that facilitate many tens of thousands of volunteers to provide services that benefit an even greater number of people across six countries.

- We work in a distributed, asynchronous way. Mostly I work from home; sometimes we get together and do things as a team (like in the photo above). Either way, I’m trusted with the autonomy to produce awesome things in the way that works best for me, backed with the help and support of a team that care with all their hearts about what we do.

- I work with amazing people who I learn from and inspire me. I mentioned one of them yesterday. But seriously, I could sing the praises of any one of our two-dozen strong team, whether for their commitment to our goals, their dedication to making the world better, their passion for quality and improvement, their focus when producing things that meet our goals, or their commitment to sticking with us for years or decades, without pay, simply because they know that what we do is important and necessary for so many worthy causes. And my fellow development/devops volunteers continue to introduce me to new things, which scratches my “drive-to-learn” itch.

- Three Rings’ commitment to diversity & inclusion is very good, and improving. We skew slightly queer and have moderately-diverse gender mix, but I’m especially impressed with our age range these days: there’s at least 50 years between our oldest and youngest volunteers with a reasonably-even spread throughout, which is super cool (and the kind of thing many voluntary organisations dream of!).

The difference

The biggest difference between these two amazing things I get to work on is… only one of them pays me. It’s hard to disregard that.

Sometimes at Automattic, I have to work on something that’s not my favourite project in the world. Or the company’s priorities clash with my own, and I end up implementing something that my gut tells me isn’t the best use of my time from a “make the world a better place” perspective. Occasionally they take a punt on something that really pisses me off.

That’s all okay, of course, because they pay me, and I have a mortgage to settle. That’s fine. That’s part of the deal.

My voluntary work at Three Rings is more… mine. I’m the founder of the project; I 100% believe in what it’s trying to achieve. Even though I’ve worked to undermine the power of my “founder privilege” by entrusting the organisation to a board and exec that I know will push back and challenge me, I feel safe fully trusting that everything I give to Three Rings will be used in the spirit of the original mission. And even though I might sometimes disagree with others on the best way forward, I accept that whatever decision is made comes from a stronger backing than if I’d acted alone.

Three Rings, of course, doesn’t pay me4. That’s why I can only give them a few hours a week of my time. If I could give more, I would, but I have bills to pay so my “day job” is important too: I’m just so incredibly fortunate that that “day job” touches upon many of the same drives that are similarly satisfied by my voluntary work.

If I didn’t have bills to pay, I could happily just volunteer for Three Rings. I’d miss Automattic, of course: there are some amazing folks there whom I love very much, and I love the work. But if they paid me as little as Three Rings did – that is, nothing! – I’d choose Three Rings in a heartbeat.

But man, what a privileged position I’m in that I can be asked what my dream job is and I can answer “well, it’s either this thing that I already do, or this other thing that I already do, depending on whether this hypothetical scenario considers money to be a relevant factor.” I’m a lucky, lucky man.

Footnotes

1 I’m badly-paraphrasing Matt, but you get the gist.

2 Automattic’s not hiring as actively nor voraciously as it has been for the last few years – a recent downtown in the tech sector which you may have seen have heavily affected many tech companies has flooded the market with talent, and we’ve managed to take our fill of them – we’re still always interested to hear from people who believe in what we do and have skills that we can make use of. And because we’re a community with a lot of bloggers, you can find plenty of first-hand experiences of our culture online if you’d like to solicit some opinions before you apply…

3 Disclaimer: Three Rings is the oldest still-running volunteer management system we’re aware of: our nearest surviving “competitor”, which provides similar-but-different features for a price that’s an order of magnitude greater, launched later in the same year we started. But maybe somebody else has been running these last 22 years that we haven’t noticed, yet: you never know!

4 Assuming you don’t count a Christmas dinner each January – yes, really! (it turns out to be cheaper to celebrate Christmas in January) – as payment.

Bisect your Priority of Constituencies

Your product, service, or organisation almost certainly has a priority of constituencies, even if it’s not written down or otherwise formally-encoded. A famous example would be that expressed in the Web Platform Design Principles. It dictates how you decide between two competing needs, all other things being equal.

At Three Rings, for example, our priority of constituencies might1 look like this:

- The needs of volunteers are more important than

- The needs of voluntary organisations, which are more important than

- Continuation of the Three Rings service, which is more important than

- Adherance to technical standards and best practice, which is more important than

- Development of new features

These are all things we care about, but we’re talking about where we might choose to rank them, relative to one another.

The priorities of an organisation you’re involved with won’t be the same: perhaps it includes shareholders, regulatory compliance, different kinds of end-users, employees, profits, different measures of social good, or various measurable outputs. That’s fine: every system is different.

But what I’d challenge you to do is find ways to bisect your priorities. Invent scenarios that pit each constituency against itself another and discuss how they should be prioritised, all other things being equal.

Using the example above, I might ask “which is more important?” in each category:

- The needs of the volunteers developing Three Rings, or the needs of the volunteers who use it?

- The needs of organisations that currently use the system, or the needs of organisations that are considering using it?

- Achieving a high level of uptime, or promptly installing system updates?

- Compliance with standards as-written, or maximum compatibility with devices as-used?

- Implementation of new features that are the most popular user requests, or those which provide the biggest impact-to-effort payoff?

The aim of the exercise isn’t to come up with a set of commandments for your company. If you come up with something you can codify, that’s great, but if you and your stakeholders just use it as an exercise in understanding the relative importance of different goals, that’s great too. Finding where people disagree is more-important than having a unifying creed2.

And of course this exercise applicable to more than just organisational priorities. Use it for projects or standards. Use it for systems where you’re the only participant, as a thought exercise. A priority of constituencies can be a beautiful thing, but you can understand it better if you’re willing to take it apart once in a while. Bisect your priorities, and see what you find.

Footnotes

1 Three Rings doesn’t have an explicit priority of constituencies: the example I give is based on my own interpretation, but I’m only a small part of the organisation.

2 Having a creed is awesome too, though, as I’ve said before.

Pronouns in Three Rings

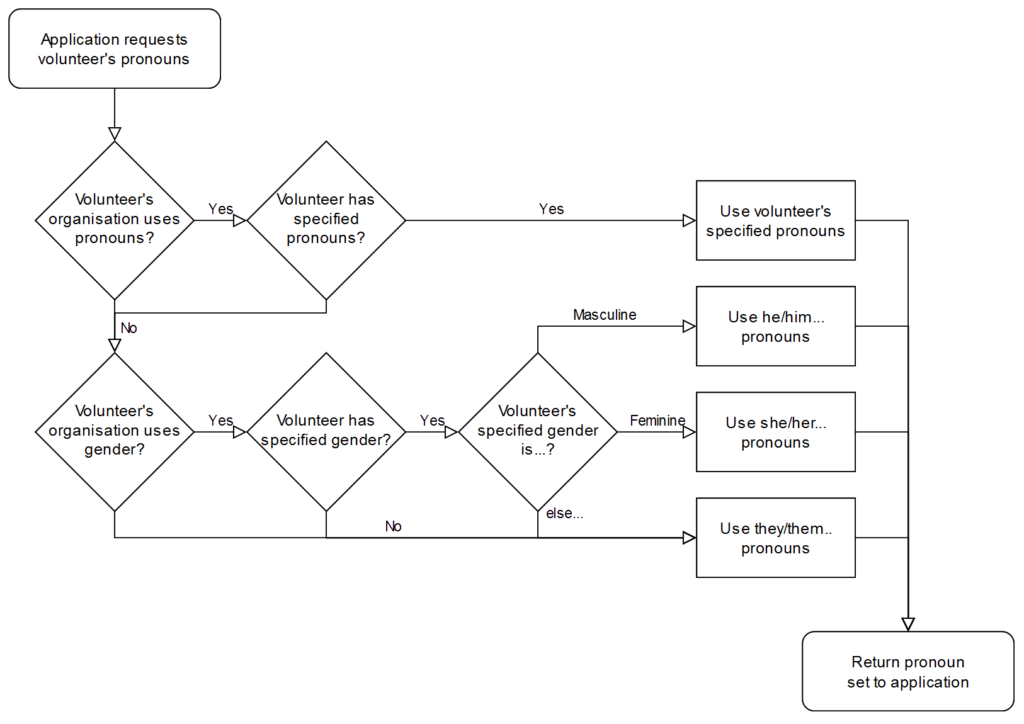

The Old Way

Prior to 2018, Three Rings had a relatively simple approach to how it would use pronouns when referring to volunteers.

If the volunteer’s gender was specified as a “masculine” gender (which particular options are available depends on the volunteer’s organisation, but might include “male”, “man”, “cis man”, and “trans man”), the system would use traditional masculine pronouns like “he”, “his”, “him” etc.

If the gender was specified as a “feminine” gender (e.g .”female”, “woman”, “cis women”, “trans woman”) the system would use traditional feminine pronouns like “she”, “hers”, “her” etc.

For any other answer, no specified answer, or an organisation that doesn’t track gender, we’d use singular “they” pronouns. Simple!

This

selection was reflected throughout the system. Three Rings might say:

This

selection was reflected throughout the system. Three Rings might say:

- They have done 7 shifts by themselves.

- She verified her email address was hers.

- Would you like to sign him up to this shift?

Unfortunately, this approach didn’t reflect the diversity of personal pronouns nor how they’re applied. It didn’t support volunteer whose gender and pronouns are not conventionally-connected (“I am a woman and I use ‘them/they’ pronouns”), nor did it respect volunteers whose pronouns are not in one of these three sets (“I use ze/zir pronouns”)… a position it took me an embarrassingly long time to fully comprehend.

So we took a new approach:

The New Way

From 2018 we allowed organisations to add a “Pronouns” property, allowing volunteers to select from 13 different pronoun sets. If they did so, we’d use it; failing that we’d continue to assume based on gender if it was available, or else use the singular “they”.

Let’s take a quick linguistics break

Three Rings‘ pronoun field always shows five personal pronouns, separated by slashes, because you can’t necessarily derive one from another. That’s one for each of five types:

- the subject, used when the person you’re talking about is primary argument to a verb (“he called”),

- object, for when the person you’re talking about is the secondary argument to a transitive verb (“he called her“),

- dependent possessive, for talking about a noun that belongs to a person (“this is their shift”),

- independent possessive, for talking about something that belongs to a person potentially would an explicit noun (“this is theirs“), and the

- reflexive (and intensive), two types which are generally the same in English, used mostly in Three Rings when a person is both the subject and indeirect of a verb (“she signed herself up to a shift”).

Let’s see what those look like – here are the 13 pronoun sets supported by Three Rings at the time of writing:

| Subject | Object | Possessive | Reflexive/intensive | |

| Dependent | Independent | |||

| he | him | his | himself | |

| she | her | hers | herself | |

| they | them | their | theirs | themselves |

| e | em | eir | eirs | emself |

| ey | eirself | |||

| hou | hee | hy | hine | hyself |

| hu | hum | hus | humself | |

| ne | nem | nir | nirs | nemself |

| per | pers | perself | ||

| thon | thons | thonself | ||

| ve | ver | vis | verself | |

| xe | xem | xyr | xyrs | xemself |

| ze | zir | zirs | zemself | |

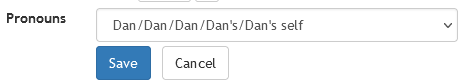

That’s all data-driven rather than hard-coded, by the way, so adding additional pronoun sets is very easy for our developers. In fact, it’s even possible for us to apply an additional “override” on an individual, case-by-case basis: all we need to do is specify the five requisite personal pronouns, separated by slashes, and Three Rings understands how to use them.

Writing code that respects pronouns

Behind the scenes, the developers use a (binary-gendered, for simplicity) convenience function to produce output, and the system corrects for the pronouns appropriate to the volunteer in question:

<%= @volunteer.his_her.capitalize %> account has been created for <%= @volunteer.him_her %> so <%= @volunteer.he_she %> can now log in.

The code above will, dependent on the pronouns specified for the volunteer @volunteer, output something like:

- His account has been created for him so he can now log in.

- Her account has been created for her so she can now log in.

- Their account has been created for them so they can now log in.

- Eir account has been created for em so ey can now log in.

- Etc.

We’ve got extended functions to automatically detect cases where the use of second person pronouns might be required (“Your account has been created for you so you can now log in.”) as well as to help us handle the fact that we say “they are” but “he/she/ey/ze/etc. is“.

It’s all pretty magical and “just works” from a developer’s perspective. I’m sure most of our volunteer developers don’t think about the impact of pronouns at all when they code; they just get on with it.

Is that a complete solution?

Does this go far enough? Possibly not. This week, one of our customers contacted us to ask:

Is there any way to give the option to input your own pronouns? I ask as some people go by she/them or he/them and this option is not included…

You can probably see what’s happened here: some organisations have taken our pronouns property – which exists primarily to teach the system itself how to talk about volunteers – and are using it to facilitate their volunteers telling one another what their pronouns are.

What’s the difference? Well:

When a human discloses that their pronouns are “she/they” to another human, they’re saying “You can refer to me using either traditional feminine pronouns (she/her/hers etc.) or the epicene singular ‘they’ (they/their/theirs etc.)”.

But if you told Three Rings your pronouns were “she/her/their/theirs/themselves”, it would end up using a mixture of the two, even in the same sentence! Consider:

- She has done 7 shifts by themselves.

- She verified her email address was theirs.

That’s some pretty clunky English right there! Mixing pronoun sets for the same person within a sentence is especially ugly, but even mixing them within the same page can cause confusion. We can’t trivially meet this customer’s request simply by adding new pronoun sets which mix things up a bit! We need to get smarter.

A Newer Way?

Ultimately, we’re probably going to need to differentiate between a more-rigid “what pronouns should Three Rings use when talking about you” and a more-flexible, perhaps optional “what pronouns should other humans use for you”? Alternatively, maybe we could allow people to select multiple pronoun sets to display but Three Rings would only use one of them (at least, one of them at a time!): “which of the following sets of pronouns do you use: select as many as apply”?

Even after this, there’ll always be more work to do.

For instance: I’ve met at least one person who uses no pronouns! By this, they actually mean they use no third-person personal pronouns (if they actually used no pronouns they wouldn’t say “I”, “me”, “my”, “mine” or “myself” and wouldn’t want others to say “you”, “your”, “yours” and “yourself” to them)! Semantics aside… for these people Three Rings should use the person’s name rather than a pronoun.

Maybe we can get there one day.

But so long as Three Rings continues to remain ahead of the curve in its respect for and understanding of pronoun use then I’ll be happy.

Our mission is to focus on volunteers and make volunteering easier. At the heart of that mission is treating volunteers with respect. Making sure our system embraces the diversity of the 65,000+ volunteers who use it by using pronouns correctly might be a small part of that, but it’s a part of it, and I for one am glad we make the effort.

Dan Q found GC5MYFN 01 It’s a Bugs Life x2

This checkin to GC5MYFN 01 It's a Bugs Life x2 reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead a quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

Passed another couple of ‘cachers on the way from GC840TN, but it sounded like they’d been having less luck than us this morning. Coordinates spot on; dropped me right on top of the cache and I was familiar with this kind of container so I picked it up as soon as I got there – quick and easy find, and our last for the morning! TFTC.

Dan Q found GC840TN Georassic Diplodocus

This checkin to GC840TN Georassic Diplodocus reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead a quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

Coordinates didn’t put us very close: perhaps because of tree cover interfering with the GPSr; we needed to decipher the hint. The hint was good, though, and I went straight to the dino’s hiding place, trampled past a few fresh nettles, and retreived it. Excellent caches; we loved these!

Dan Q found GC5MYFW 02 It’s a Bugs Life x2

This checkin to GC5MYFW 02 It's a Bugs Life x2 reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead Ga quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

Geoff pounced right onto this one, stunning some of our less-experienced ‘cachers who’d never considered the possibility of a container like this!

Dan Q found GC3JG9P Georassic – Stegosaurus

This checkin to GC3JG9P Georassic - Stegosaurus reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead a quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

Our tagalong 5-year-old and 2-year-old co-found this one; they were pretty much an ideal size to get to the GZ. This was the last of the three caches they attended; they went back to their cabin after this but most of the adults carried on.

Dan Q found GC840T0 Georassic Parasaurolophus

This checkin to GC840T0 Georassic Parasaurolophus reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead a quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

So THAT is what a Parasaurolophus looks like! Swiftly found by our tame 5 year-old, who was especially delighted to pull a dinosaur out of its hiding place.

Dan Q found GC3JG92 Georassic – Spinosaurus

This checkin to GC3JG92 Georassic - Spinosaurus reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Some fellow volunteers and I are on an “away weekend” in the forest; this morning before our first meeting I lead a quick expedition of both established and first-timer geocachers around a few of the local caches.

After a bit of an extended hunt (this dino was well-hidden!) we found this first container; delighted by the theming of this series; FP awarded here for the ones we found.