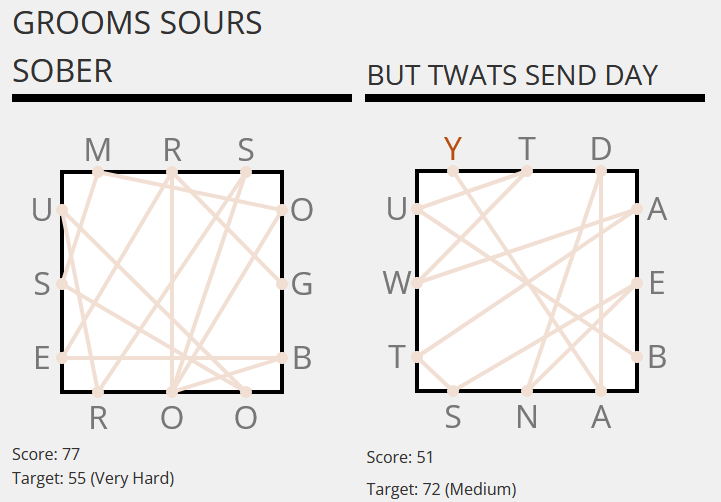

I’ve been enjoying playing Chain Words, from eclectech, intermittently, since it came out in November (when I complained that the word ‘TOSSPOT’ was rejected; I don’t know if this obvious omission has yet been corrected). If you’ve not given it a go yet, and you like a word game that’s “a bit different”, you should try it!

Tag: puzzles

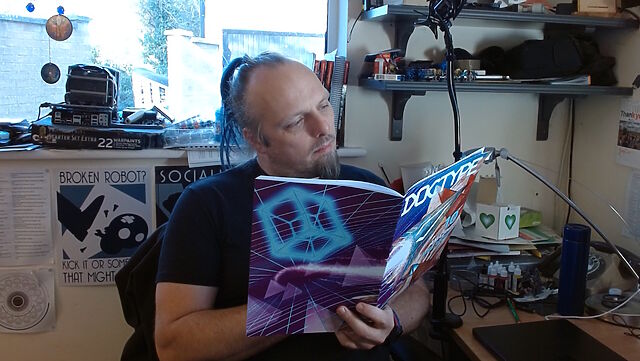

DOCTYPE

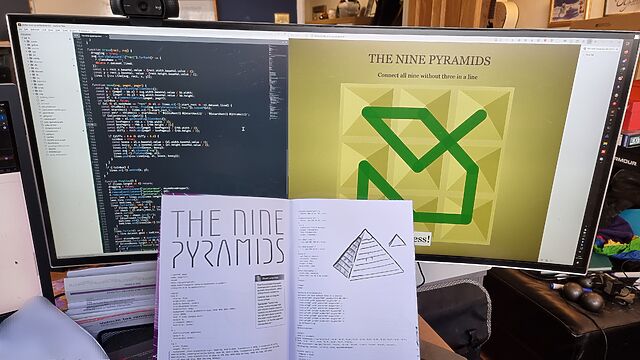

This weekend, I received my copy of DOCTYPE, and man: it feels like a step back to yesteryear to type in a computer program from a magazine: I can’t have done that in at least thirty years.

So yeah, DOCTYPE is a dead-tree (only) medium magazine containing the source code to 10 Web pages which, when typed-in to your computer, each provide you with some kind of fun and interactive plaything. Each of the programs is contributed by a different author, including several I follow and one or two whom I’m corresponded with at some point or another, and each brings their own personality and imagination to their contribution.

I opted to start with Stuart Langridge‘s The Nine Pyramids, a puzzle game about trying to connect all nodes in a 3×3 grid in a continuous line bridging adjacent (orthogonal or diagonal) nodes without visiting the same node twice nor moving in the same direction twice in a row (that last provision is described as “not visiting three in a straight line”, but I think my interpretation would have resulted in simpler code: I might demonstrate this, down the line!).

Per tradition with this kind of programming, I made a couple of typos, the worst of which was missing an entire parameter in a CSS conic-gradient() which resulted in the

majority of the user interface being invisible: whoops! I found myself reminded of typing-in the code for Werewolves and

Wanderer from The Amazing Amstrad Omnibus, whose data section – the part most-liable to be affected by a typographic bug without introducing a syntax error – had

a helpful “checksum” to identify if a problem had occurred, and wishing that such a thing had been possible here!

But thankfully a tiny bit of poking in my browser’s inspector revealed the troublesome CSS and I was able to complete the code, and then the puzzle.

I’ve really been enjoying DOCTYPE, and you can still buy a copy if you’d like one of your own. It manages to simultaneously feel both fresh and nostalgic, and that’s really cool.

Impossible Countdown

Or: Sometimes You Don’t Need a Computer, Just a Brain

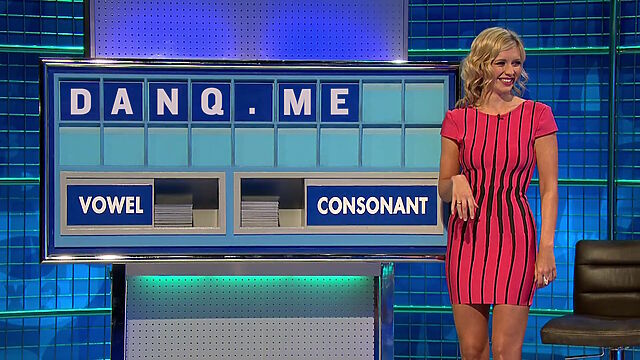

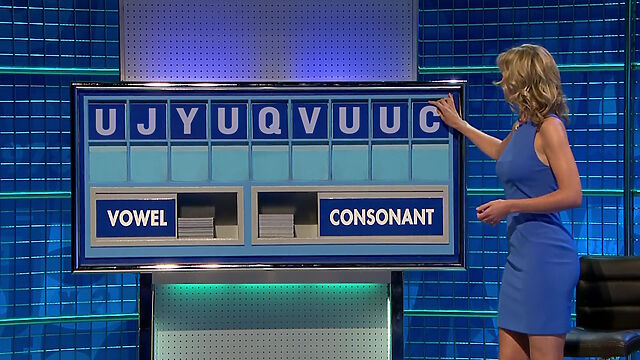

I was watching an episode of 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown the other night1 and I was wondering: what’s the hardest hand you can be dealt in a Countdown letters game?

Sometimes it’s possible to get fixated on a particular way of solving a problem, without having yet fully thought-through it. That’s what happened to me, because the first thing I did was start to write a computer program to solve this question. The program, I figured, would permute through all of the legitimate permutations of letters that could be drawn in a game of Countdown, and determine how many words and of what length could be derived from them2. It’d repeat in this fashion, at any given point retaining the worst possible hands (both in terms of number of words and best possible score).

When the program completed (or, if I got bored of waiting, when I stopped it) it’d be showing the worst-found deals both in terms of lowest-scoring-best-word and fewest-possible-words. Easy.

Here’s how far I got with that program before I changed techniques. Maybe you’ll see why:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby WORDLIST = File.readlines('dictionary.txt').map(&:strip) # https://github.com/jes/cntdn/blob/master/dictionary LETTER_FREQUENCIES = { # http://www.thecountdownpage.com/letters.htm vowels: { A: 15, E: 21, I: 13, O: 13, U: 5, }, consonants: { B: 2, C: 3, D: 6, F: 2, G: 3, H: 2, J: 1, K: 1, L: 5, M: 4, N: 8, P: 4, Q: 1, R: 9, S: 9, T: 9, V: 1, W: 1, X: 1, Y: 1, Z: 1, } } ALLOWED_HANDS = [ # https://wiki.apterous.org/Letters_game { vowels: 3, consonants: 6 }, { vowels: 4, consonants: 5 }, { vowels: 5, consonants: 4 }, ]

At this point in writing out some constants I’d need to define the rules, my brain was already racing ahead to find optimisations.

For example: given that you must choose at least four cards from the consonants deck, you’re allowed no more than five vowels… but no individual vowel appears in the vowel deck fewer than five times, so my program actually had free-choice of the vowels.

Knowing that3, I figured that there must exist Countdown deals that contain no valid words, and that finding one of those would be easier than writing a program to permute through all viable options. My head’s full of useful heuristics about English words, after all, which leads to rules like:

- None of the vowels can be I or A, because they’re words in their own right.

- Five letter Us is a strong starting point, because it’s very rarely used in two-letter words (and this set of tiles is likely to be hard enough that three-letter words are already an impossibility).

- This eliminates the consonants M (mu, um: the Greek letter and the “I’m thinking” sound), N (nu, un-: the Greek letter and the inverting prefix), H (uh: another sound for when you’re thinking or hesitating), P (up: the direction of ascension), R (ur-: the prefix for “original”), S (us: the first-person-plural pronoun), and X (xu: the unit of currency). So as long as we can find four consonants within the allowable deck letter frequency that aren’t those five… we’re sorted.

I enjoyed getting “Q” into my proposed letter set. I like to image a competitor, having already drawn two “U”s, a “J”, and a Y”, being briefly happy to draw a “Q” and already thinking about all those “QU-” words that they’re excited to be able to use… before discovering that there aren’t any of them and, indeed, aren’t actually any words at all.

Even up to the last letter they were probably hoping for some consonant that could make it work. A K (juku), maybe?

But the moral of the story is: you don’t always have to use a computer. Sometimes all you need is a brain and a few minutes while you eat your breakfast on a slow Sunday morning, and that’s plenty sufficient.

Update: As soon as I published this, I spotted my mistake. A “yuzu” is a kind of East Asian plum, but it didn’t show up in this countdown solver! So my impossible deal isn’t quite so impossible after all. Perhaps U J Y U Q V U U C would be a better “impossible” set of tiles, where that “C” makes it briefly look like there might be a word in there, even if it’s just a three or four-letter one… but there isn’t. Or is there…?

Footnotes

1 It boggles my mind to realise that show’s managed 28 seasons, now. Sure, I know that Countdown has managed something approaching 9,000 episodes by now, but Cats Does Countdown was always supposed to be a silly one-off, not a show in it’s own right. Anyway: it’s somehow better than both 8 Out Of 10 Cats and Countdown, and if you disagree then we can take this outside.

2 Herein lay my first challenge, because it turns out that the letter frequencies and even the rules of Countdown have changed on several occasions, and short of starting a conversation on what might be the world’s nerdiest surviving phpBB installation I couldn’t necessarily determine a completely up-to-date ruleset.

3 And having, y’know, a modest knowledge of the English language

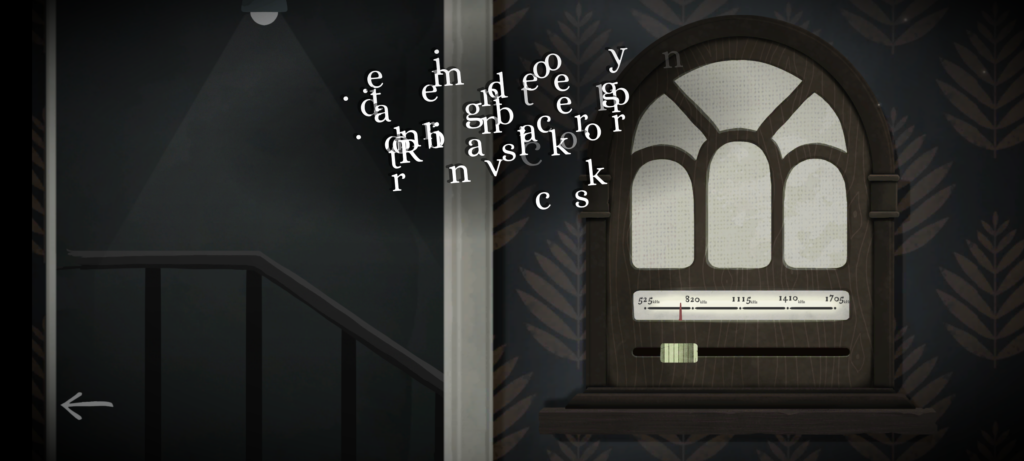

More castles and mazes

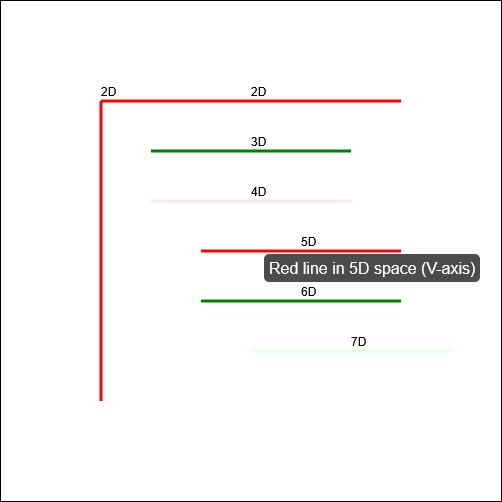

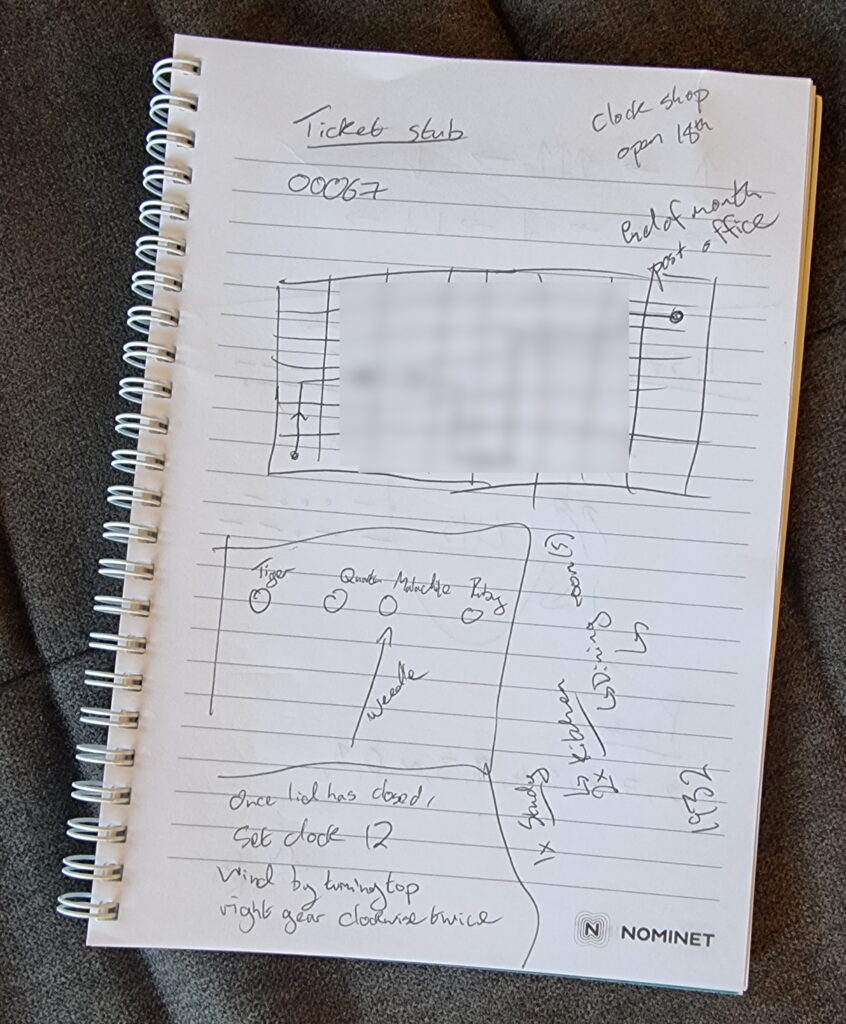

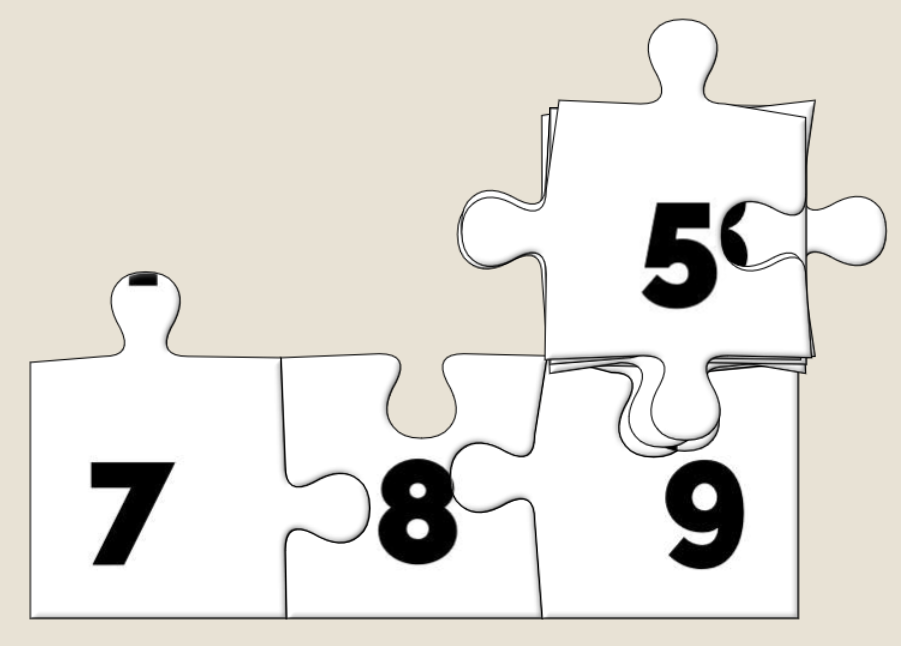

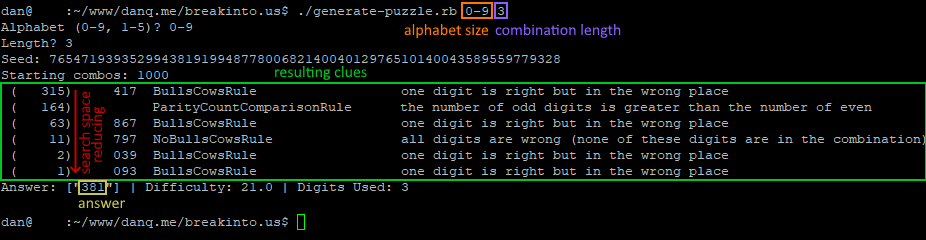

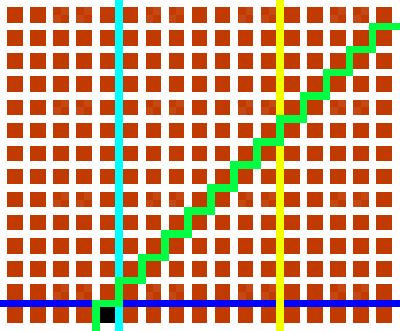

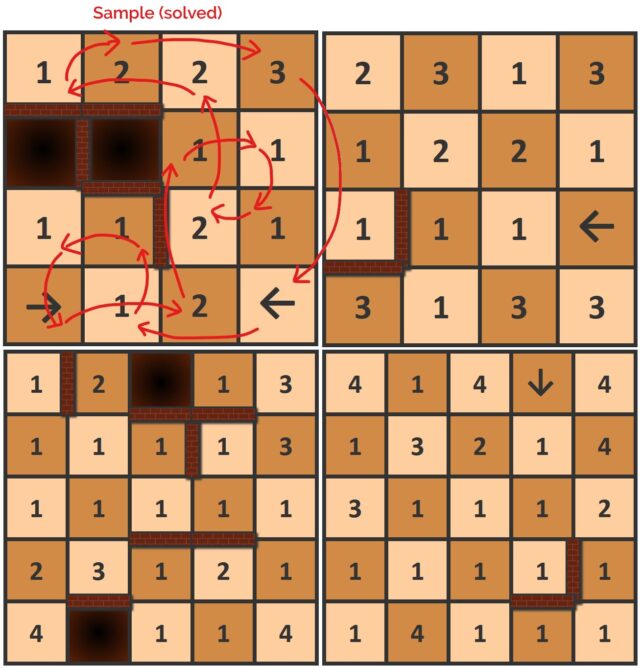

Made a little progress on the game idea I’d been experimenting with. The idea is to do find a series of orthogonal (like a rook in chess!) moves that land on every square exactly once each before returning to the start, dodging walls and jumping pits.

But the squares have arrows (limiting the direction you can move out of them) or numbers (specifying the distance you must travel from them).

Every board is solvable, starting from any square. There’ll be a playable version to use on your device (with helpful features like “undo”) sometime soon, but for now you can give them a go by hand, if you like this kind of puzzle!

Castles and mazes

AI vs The Expert

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

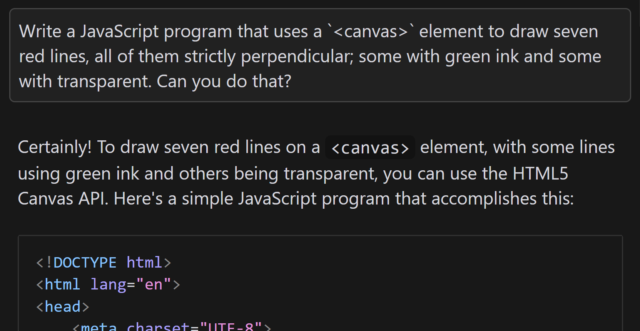

The Expert

Eleven years ago, comedy sketch The Expert had software engineers (and other misunderstood specialists) laughing to tears at the relatability of Anderson’s (Orion Lee) situation: asked to do the literally-impossible by people who don’t understand why their requests can’t be fulfilled.

Decades ago, a client wanted their Web application to automatically print to the user’s printer, without prompting. I explained that it was impossible because “if a website could print to your printer without at least asking you first, everybody would be printing ads as you browsed the web”. The client’s response: “I don’t need you to let everybody print. Just my users.”1

So yeah, I was among those that sympathised with Anderson.

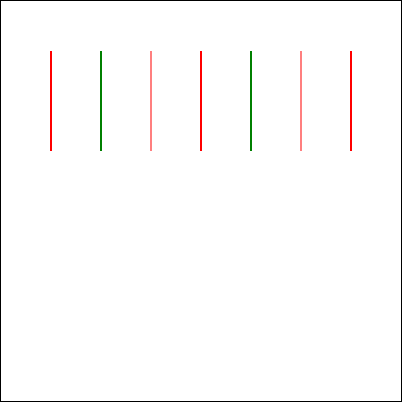

In the sketch, the client requires him to “draw seven red lines, all of them strictly perpendicular; some with green ink and some with transparent”. He (reasonably) states that this is impossible2.

Versus AI

Following one of the many fever dreams when I was ill, recently, I woke up wondering… how might an AI programmer tackle this task? I had an inkling of the answer, so I had to try it:

<canvas> element3, the

question is the same as in the sketch.

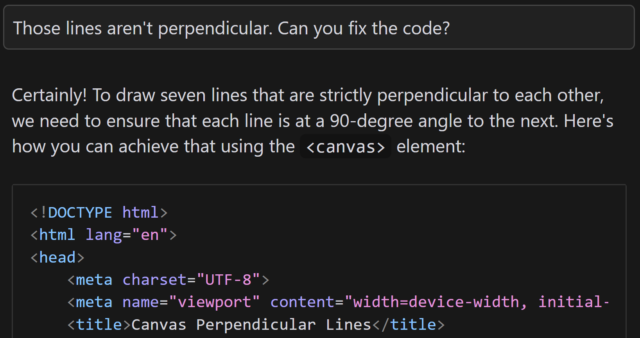

When I asked gpt-4o to assist me, it initially completely ignored the perpendicularity requirement.

Let’s see if it can do better, with a bit of a nudge:

gpt-4o claimed that the task was absolutely achievable, even clarifying that the lines would all be “strictly perpendicular to each other”… before proceeding to instead

make each consecutively-drawn line be perpendicular only to its predecessor:

You might argue that this test is unfair, and it is. But there’s a point that I’ll get to.

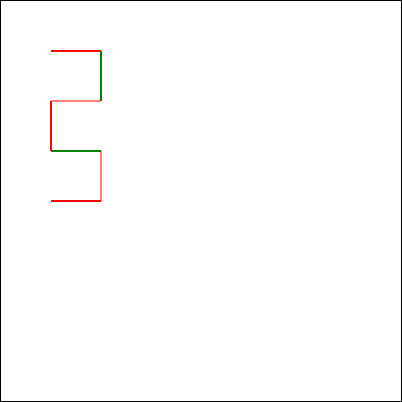

But first, let me show you how a different model responded. I tried the same question with the newly-released Claude 3.7 Sonnet model, and got what I’d consider to be a much better answer:

In my mind: an ideal answer acknowledges the impossibility of the question, or at least addresses the supposed-impossibility of it. Claude 3.7 Sonnet did well here, although I can’t confirm whether it did so because it had been trained on data that recognised the existence of “The Expert” or not (it’s clearly aware of the sketch, given its answer).

What’s the point, Dan?

I remain committed to not using AI to do anything I couldn’t do myself (and can therefore check).4

And the answer I got from gpt-4o to this question goes a long way to demonstrating why.

Suppose I didn’t know that it was impossible to make seven lines perpendicular to one another in anything less than seven-dimensional space. If that were the case, it’d be tempting to accept an AI-provided answer as correct, and ship it. And while that example is trivial (and at least a little bit silly), it’s the kind of thing that, I have no doubt, actually happens in other areas.

Chatbots eagerness to provide a helpful answer, even if no answer is possible, is a huge liability. The other week, I experimentally asked Claude 3.5 for assistance with a PHPUnit mocking challenge and it provided a whole series of answers… that were completely invalid! It later turned out that what I was trying to achieve was impossible5.

Given that its answers clearly didn’t-work there was no risk I’d have shipped it anyway, but I’m certain that there exist developers who’ve asked a chatbot for help in a domain they didn’t understood and accepted its answer while still not understanding it, which feels to me like a quick route to introducing into your code a bug that happy-path testing won’t reveal. (Y’know, something like a security vulnerability, or an accessibility failure, or whatever.)

Code assisting AI remains really interesting and occasionally useful… but it’s also a real minefield and I see a lot of naiveté about its limitations.

Footnotes

1 My client eventually took that particular requirement out of scope and I thought the matter was settled, but I heard that they later contracted a different developer to implement just that bit of functionality into the application that we delivered. I never checked, but I think that what they delivered exploited ActiveX/Java applet vulnerabilities to achieve the goal.

2 Nerds gotta nerd, and so there’s been endless debate on the Internet about whether the task is truly impossible. For example, when I first saw the video I was struck by the observation that perpendicularity within a set of lines is limited linearly by the number of dimensions you’re working in, so it’s absolutely possible to model seven lines all perpendicular to one another… if you’re working in seven dimensions. But let’s put that all aside for a moment and assume the task is truly impossible within some framework unspecified-but-implied within the universe of the sketch, ‘k?

3 Two-dimensionality feels like a fair assumed constraint, given that in the sketch Anderson tries to demonstrate the challenges of the task by using a flip-chart.

4 I also don’t use AI to produce anything creative that I then pass off as my own, because, y’know, many of these models don’t seem to respect copyright. You won’t find any AI-written content on my blog, for example, except specifically to demonstrate AI’s capabilities (or lack thereof) when discussing AI, and this is always be clearly labelled. But that’s another question.

5 In fact, I was going about the problem itself in entirely the wrong way: some minor refactoring later and I had some solid unit tests that fit the bill, and I didn’t need to do the impossible. But the AI never clocked that, and I suspect it never would have.

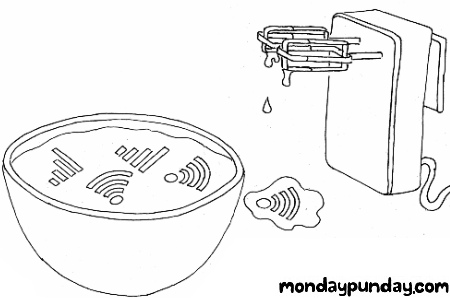

Monday Punday

Have you come across Monday Punday? I only discovered it last year, sadly, after it had been on hiatus for like 4 years, following a near decade-long run, but I figured that if you like wordplay and webcomics as much as I do (e.g. if you enjoyed my Movie Title Mash-Ups, back in the day), then perhaps you’ll dig it too.

I’ve been gradually making my way through the back catalogue, guessing the answers (there’s a form that’ll tell you if you’re right!). I’ve successfully guessed almost half of all of them, now, and it’s been a great journey. It sort-of fills the void that I’d hoped Crimson Herring was going to before it vanished so suddenly.

So if you’re looking for a fresh, probably-finished webcomic that’ll sometimes make you laugh, sometimes make you groan, and often make you think, start by skimming the rules of Monday Punday and then begin the long journey through the ~500 published episodes. You’re welcome!

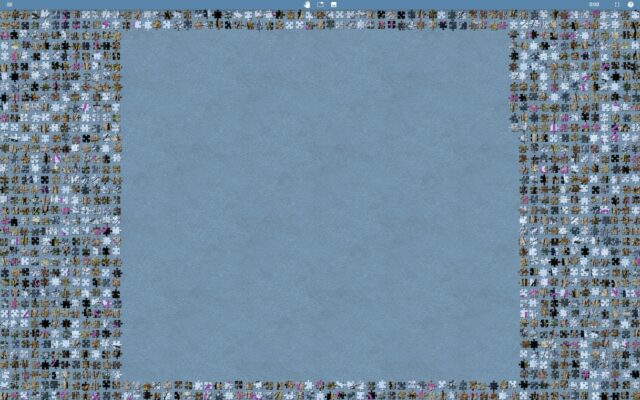

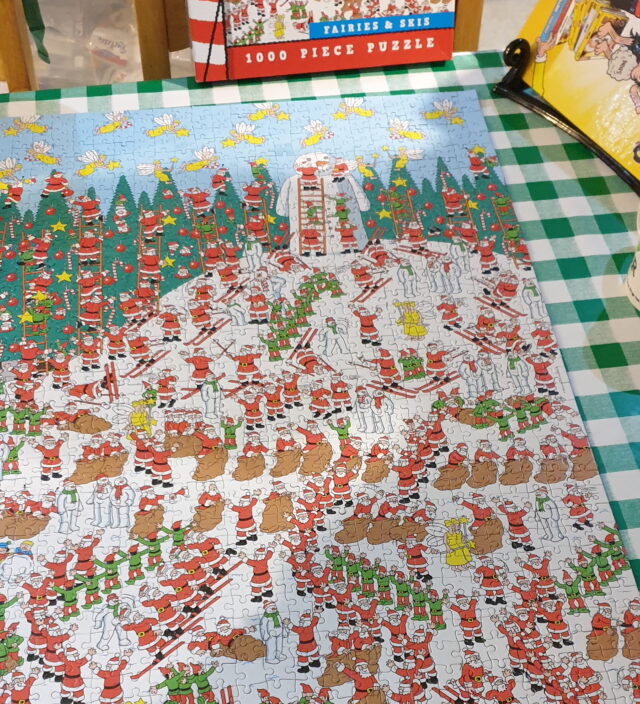

Quickly Solving JigsawExplorer Puzzles

Background

I was contacted this week by a geocacher called Dominik who, like me, loves geocaching…. but hates it when the coordinates for a cache are hidden behind a virtual jigsaw puzzle.

A popular online jigsaw tool used by lazy geocache owners is Jigidi: I’ve come up with several techniques for bypassing their puzzles or at least making them easier.

Dominik had been looking at a geocache hidden last week in Eastern France and had discovered that it used JigsawExplorer, not Jigidi, to conceal the coordinates. Let’s take a look…

I experimented with a few ways to work-around the jigsaw, e.g. dramatically increasing the “snap range” so dragging a piece any distance would result in it jumping to a neighbour, and extracting original image URLs from localStorage. All were good, but none were perfect.

Then I realised that – unlike Jigidi, where there can be a congratulatory “completion message” (with e.g. geocache coordinates in) – in JigsawExplorer the prize is seeing the completed jigsaw.

Let’s work on attacking that bit of functionality. After all: if we can bypass the “added challenge” we’ll be able to see the finished jigsaw and, therefore, the geocache coordinates. Like this:

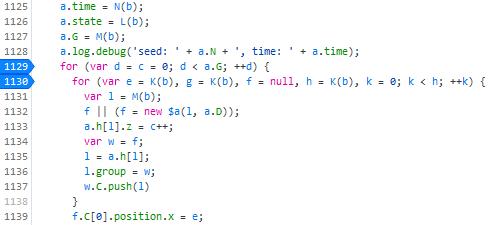

Hackaround

- Open a jigsaw and try the “box cover” button at the top. If you get the message “This puzzle’s box top preview is disabled for added challenge.”, carry on.

- Open your browser’s debug tools (F12) and navigate to the Sources tab.

- Find the

jigex-prog.jsfile. Right-click and select Override Content (or Add Script Override). - In the overridden version of the file, search for the string –

e&&e.customMystery?tt.msgbox("This puzzle's box top preview is disabled for added challenge."):– this code checks if the puzzle has the “custom mystery” setting switched on and if so shows the message, otherwise (after the:) shows the box cover. - Carefully delete that entire string. It’ll probably appear twice.

- Reload the page. Now the “box cover” button will work.

The moral, as always, might be: don’t put functionality into the client-side JavaScript if you don’t want the user to be able to bypass it.

Or maybe the moral is: if you’re going to make a puzzle geocache, put some work in and do something clever, original, and ideally with fieldwork rather than yet another low-effort “upload a picture and choose the highest number of jigsaw pieces to cut it into from the dropdown”.

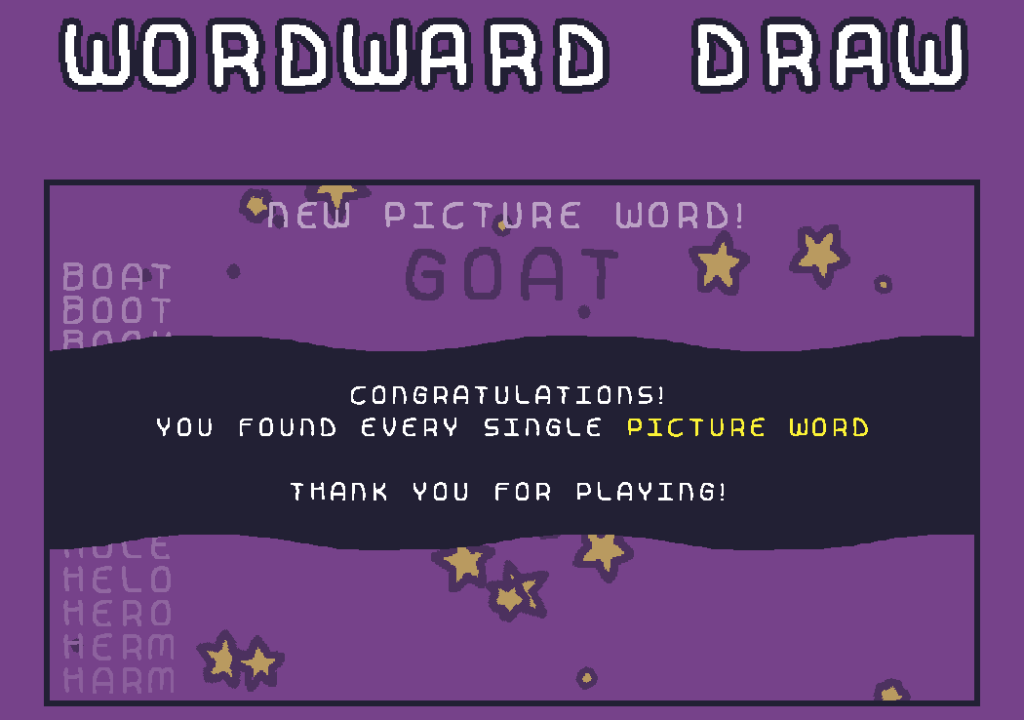

Woodward Draw

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

- Explore the set of 4 letter words

- Either change one letter of the previous word

- Or rearrange all the letters of the previous word

- Find all 105 picture words!

Woodward Draw by Daniel Linssen is the kind of game that my inner Scrabble player both loves and hates. I’ve been playing on and off for the last three days to complete it, and it’s been great. While not perfectly polished1 and with a few rough edges2, it’s still a great example of what one developer can do with a little time.

It deserves a hat tip of respect, but I hope you’ll give it more than that by going and playing it (it’s free, and you can play online or download a copy3). I should probably check out their other games!

Footnotes

1 At one point the background colour, in order to match a picture word, changed to almost the same colour as the text of the three words to find!

2 The tutorial-like beginning is a bit confusing until you realise that you have to play the turn you’re told to, to begin with, for example.

3 Downloadable version is Windows only.

The Miracle Sudoku

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I first saw this video when it was doing the rounds three years ago and was blown away. I was reminded of it recently when it appeared in a blog post about AI’s possible future role in research by Terence Eden.

I don’t even like sudoku. And if you’d told me in advance that I’d enjoy watching a man slowly solve a sudoku-based puzzle in real-time, I’d have called you crazy. But I watched it again today, for what must’ve been the third time, and it’s still magical. The artistry of puzzle creator Mitchell Lee is staggering.

If you somehow missed it the first time around, now’s your chance. Put this 25-minute video on in the background and prepare to have your mind blown.

Solving Jigidi… Again

(Just want the instructions? Scroll down.)

A year and a half ago I came up with a technique for intercepting the “shuffle” operation on jigsaw website Jigidi, allowing players to force the pieces to appear in a consecutive “stack” for ludicrously easy solving. I did this partially because I was annoyed that a collection of geocaches near me used Jigidi puzzles as a barrier to their coordinates1… but also because I enjoy hacking my way around artificially-imposed constraints on the Web (see, for example, my efforts last week to circumvent region-blocking on radio.garden).

My solver didn’t work for long: code changes at Jigidi’s end first made it harder, then made it impossible, to use the approach I suggested. That’s fine by me – I’d already got what I wanted – but the comments thread on that post suggests that there’s a lot of people who wish it still worked!2 And so I ignored the pleas of people who wanted me to re-develop a “Jigidi solver”. Until recently, when I once again needed to solve a jigsaw puzzle in order to find a geocache’s coordinates.

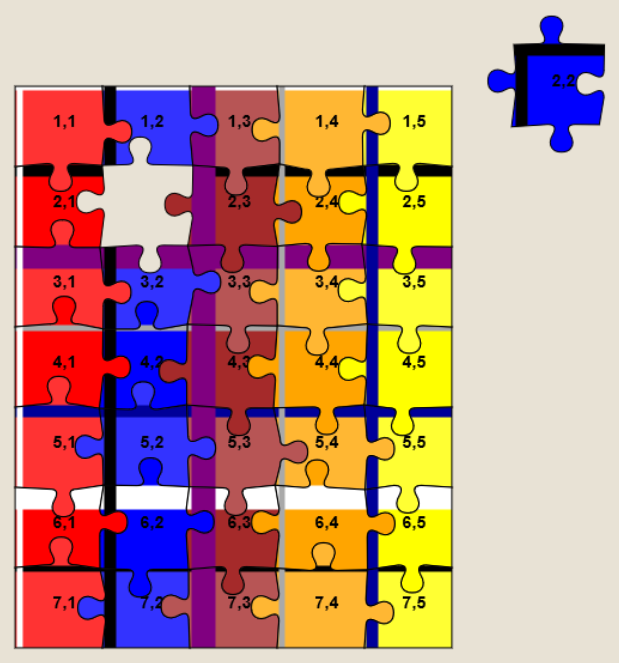

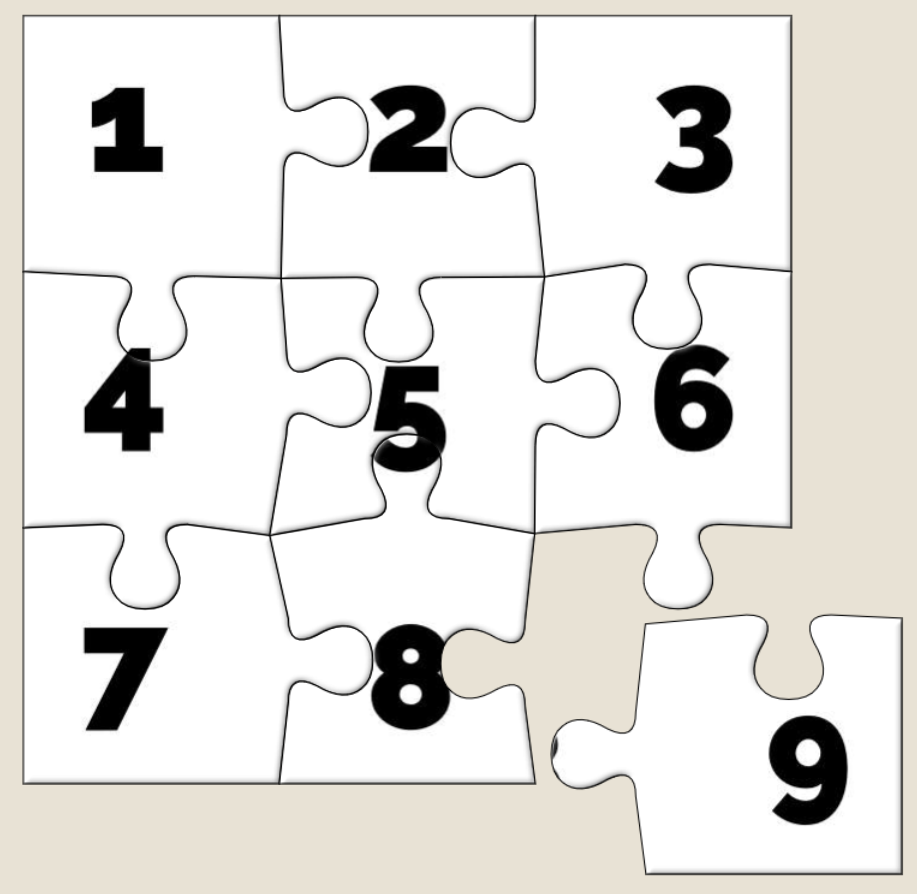

Making A Jigidi Helper

Rather than interfere with the code provided by Jigidi, I decided to take a more-abstract approach: swapping out the jigsaw’s image for one that would be easier.

This approach benefits from (a) having multiple mechanisms of application: query interception, DNS hijacking, etc., meaning that if one stops working then another one can be easily rolled-out, and (b) not relying so-heavily on the structure of Jigidi’s code (and therefore not being likely to “break” as a result of future upgrades to Jigidi’s platform).

Watch a video demonstrating the approach:

It’s not as powerful as my previous technique – more a “helper” than a “solver” – but it’s good enough to shave at least half the time off that I’d otherwise spend solving a Jigidi jigsaw, which means I get to spend more time out in the rain looking for lost tupperware. (If only geocaching were even the weirdest of my hobbies…)

How To Use The Jigidi Helper

To do this yourself and simplify your efforts to solve those annoying “all one colour” or otherwise super-frustrating jigsaw puzzles, here’s what you do:

- Visit a Jigidi jigsaw. Do not be logged-in to a Jigidi account.

- Copy my JavaScript code into your clipboard.

- Open your browser’s debug tools (usually F12). In the Console tab, paste it and press enter. You can close your debug tools again (F12) if you like.

- Press Jigidi’s “restart” button, next to the timer. The jigsaw will restart, but the picture will be replaced with one that’s easier-to-solve than most, as described below.

- Once you solve the jigsaw, the image will revert to normal (turn your screen around and show off your success to a friend!).

What makes it easier to solve?

The replacement image has the following characteristics that make it easier to solve than it might otherwise be:

- Every piece has written on it the row and column it belongs in.

- Every “column” is striped in a different colour.

- Striped “bands” run along entire rows and columns.

To solve the jigsaw, start by grouping colours together, then start combining those that belong in the same column (based on the second digit on the piece). Join whole or partial columns together as you go.

I’ve been using this technique or related ones for over six months now and no code changes on Jigidi’s side have impacted upon it at all, so it’s probably got better longevity than the previous approach. I’m not entirely happy with it, and you might not be either, so feel free to fork my code and improve it: the legiblity of the numbers is sometimes suboptimal, and the colour banding repeats on larger jigsaws which I’d rather avoid. There’s probably also potential to improve colour-recognition by making the colour bands span the gaps between rows or columns of pieces, too, but more experiments are needed and, frankly, I’m not the right person for the job. For the second time, I’m going to abandon a tool that streamlines Jigidi solving because I’ve already gotten what I needed out of it, and I’ll leave it up to you if you want to come up with an improvement and share it with the community.

Footnotes

1 As I’ve mentioned before, and still nobody believes me: I’m not a fan of jigsaws! If you enjoy them, that’s great: grab a bucket of popcorn and a jigsaw and go wild… but don’t feel compelled to share either with me.

2 The comments also include asuper-helpful person called Rich who’s been manually solving people’s puzzles for them, and somebody called Perdita who “could be my grandmother” (except: no) with whom I enjoyed a conversation on- and off-line about the ethics of my technique. It’s one of the most-popular comment threads my blog has ever seen.

STAR T/W R/A E/R K/S

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Fun little trick in the Sunday New York Times crossword yesterday: the central theme clue was “The better of two sci-fi franchises”, and regardless of whether you put Star Wars or Star Trek, the crossing clues worked

This is a (snippet of an) excellent New York Times crossword puzzle, but the true genius of it in my mind is that 71 down can be answered using iconic Star Wars line “It’s a trap!” only if the player puts Star Trek, rather than Star Wars, as the answer to 70 across (“The better of two sci-fi franchises”). If they answer with Star Wars, they instead must answer “It’s a wrap!”.

Matt goes on to try to make his own which pairs 1954 novel Lord of the Rings against Lord of the Flies, which is pretty good but I’m not convinced he can get away with the crosswise “ulne” as a word (contrast e.g. “rise” in the example above).

Of course, neither are quite as clever as the New York Times‘ puzzle on the eve of the 1996 presidential election whose clue “Lead story in tomorrow’s newspaper(!)” could be answered either “Clinton elected” or “Bob Dole elected” and the words crossing each of “Clinton” or “Bob Dole” would still fit the clues (despite being modified by only a single letter).

If you’re looking to lose some time, here’s some further reading on so-called “Schrödinger puzzles”, and several more crosswords that achieve the same feat.

Tick Tock

Looking for something with an “escape room” vibe for our date night this week, Ruth and I tried Tick Tock: A Tale for Two, a multiplayer simultaneous cooperative play game for two people, produced by Other Tales Interactive. It was amazing and I’d highly recommend it.

The game’s available on a variety of platforms: Windows, Mac, Android, iOS, and Nintendo Switch. We opted for the Android version because, thanks to Google Play Family Library, this meant we only had to buy one copy (you need it installed on both devices you’re playing it on, although both devices don’t have to be of the same type: you could use an iPhone and a Nintendo Switch for example).

The really clever bit from a technical perspective is that the two devices don’t communicate with one another. You could put your devices in flight mode and this game would still work just fine! Instead, the gameplay functions by, at any given time, giving you either (a) a puzzle for which the other person’s device will provide the solution, or (b) a puzzle that you both share, but for which each device only gives you half of the clues you need. By working as a team and communicating effectively (think Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes but without the time pressure), you and your partner will solve the puzzles and progress the plot.

(We’re purists for this kind of puzzle game so we didn’t look at one another’s screens, but I can see how it’d be tempting to “cheat” in this way, especially given that even the guys in the trailer do so!)

The puzzles start easy enough, to the extent that we were worried that the entire experience might not be challenging for us. But the second of the three acts proved us wrong and we had to step up our communication and coordination, and the final act had one puzzle that had us scratching our heads for some time! Quite an enjoyable difficulty curve, but still balanced to make sure that we got to a solution, together, in the end. That’s a hard thing to achieve in a game, and deserves praise.

The plot is a little abstract at times and it’s hard to work out exactly what role we, the protagonists, play until right at the end. That’s a bit of a shame, but not in itself a reason to reject this wonderful gem of a game. We spent 72 minutes playing it, although that includes a break in the middle to eat a delivery curry.

If you’re looking for something a bit different for a quiet night in with somebody special, it’s well worth a look.

Quickly Solving Jigidi Puzzles

tl;dr? Just want instructions on how to solve Jigidi puzzles really fast with the help of your browser’s dev tools? Skip to that bit.

This approach doesn’t work any more. Want to see one that still does (but isn’t quite so automated)? Here you go!

I don’t enjoy jigsaw puzzles

I enjoy geocaching. I don’t enjoy jigsaw puzzles. So mystery caches that require you to solve an online jigsaw puzzle in order to get the coordinates really don’t do it for me. When I’m geocaching I want to be outdoors exploring, not sitting at my computer gradually dragging pixels around!

Many of these mystery caches use Jigidi to host these jigsaw puzzles. An earlier version of Jigidi was auto-solvable with a userscript, but the service has continued to be developed and evolve and the current version works quite hard to make it hard for simple scripts to solve. For example, it uses a WebSocket connection to telegraph back to the server how pieces are moved around and connected to one another and the server only releases the secret “you’ve solved it” message after it detects that the pieces have been arranged in the appropriate relative configuration.

If there’s one thing I enjoy more than jigsaw puzzles – and as previously established there are about a billion things I enjoy more than jigsaw puzzles – it’s reverse-engineering a computer system to exploit its weaknesses. So I took a dive into Jigidi’s client-side source code. Here’s what it does:

- Get from the server the completed image and the dimensions (number of pieces).

- Cut the image up into the appropriate number of pieces.

- Shuffle the pieces.

- Establish a WebSocket connection to keep the server up-to-date with the relative position of the pieces.

- Start the game: the player can drag-and-drop pieces and if two adjacent pieces can be connected they lock together. Both pieces have to be mostly-visible (not buried under other pieces), presumably to prevent players from just making a stack and then holding a piece against each edge of it to “fish” for its adjacent partners.

Looking at that process, there’s an obvious weak point – the shuffling (point 3) happens client-side, and before the WebSocket sync begins. We could override the shuffling function to lay the pieces out in a grid, but we’d still have to click each of them in turn to trigger the connection. Or we could skip the shuffling entirely and just leave the pieces in their default positions.

And what are the default positions? It’s a stack with the bottom-right jigsaw piece on the top, the piece to the left of it below it, then the piece to the left of that and son on through the first row… then the rightmost piece from the second-to-bottom row, then the piece to the left of that, and so on.

That’s… a pretty convenient order if you want to solve a jigsaw. All you have to do is drag the top piece to the right to join it to the piece below that. Then move those two to the right to join to the piece below them. And so on through the bottom row before moving back – like a typewriter’s carriage return – to collect the second-to-bottom row and so on.

How can I do this?

If you’d like to cheat at Jigidi jigsaws, this approach works as of the time of writing. I used Firefox, but the same basic approach should work with virtually any modern desktop web browser.

- Go to a Jigidi jigsaw in your web browser.

- Pop up your browser’s developer tools (F12, usually) and switch to the Debugger tab. Open the file

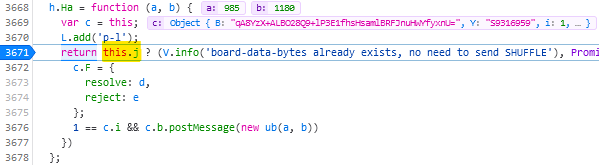

game/js/release.jsand uncompress it by pressing the {} button, if necessary. - Find the line where the code considers shuffling; right now for me it’s like 3671 and looks like this:

return this.j ? (V.info('board-data-bytes already exists, no need to send SHUFFLE'), Promise.resolve(this.j)) : new Promise(function (d, e) {

I spent some time tracing call stacks to find this line… only to discover that it’s one of only four lines to actually contain the word “shuffle” and I could have just searched for it… - Set a breakpoint on that line by clicking its line number.

- Restart the puzzle by clicking the restart button to the right of the timer. The puzzle will reload but then stop with a “Paused on breakpoint” message. At this point the

application is considering whether or not to shuffle the pieces, which normally depends on whether you’ve started the puzzle for the first time or you’re continuing a saved puzzle from

where you left off.

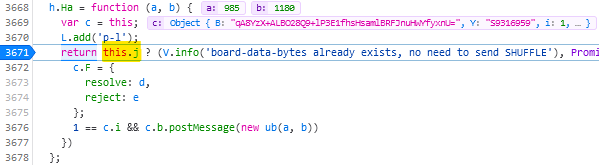

- In the developer tools, switch to the Console tab.

- Type:

this.j = true(this ensures that the ternary operation we set the breakpoint on will resolve to the true condition, i.e. not shuffle the pieces).

- Press the play button to continue running the code from the breakpoint. You can now close the developer tools if you like.

- Solve the puzzle as described/shown above, by moving the top piece on the stack slightly to the right, repeatedly, and then down and left at the end of each full row.

Update 2021-09-22: Abraxas observes that Jigidi have changed

their code, possibly in response to this shortcut. Unfortunately for them, while they continue to perform shuffling on the client-side they’ll always be vulnerable to this kind of

simple exploit. Their new code seems to be named not release.js but given a version number; right now it’s 14.3.1977. You can still expand it in the same way,

and find the shuffling code: right now for me this starts on line 1129:

Put a breakpoint on line 1129. This code gets called twice, so the first time the breakpoint gets hit just hit continue and play on until the second time. The second time it gets hit,

move the breakpoint to line 1130 and press continue. Then use the console to enter the code d = a.G and continue. Only one piece of jigsaw will be shuffled; the rest will

be arranged in a neat stack like before (I’m sure you can work out where the one piece goes when you get to it).

Update 2023-03-09: I’ve not had time nor inclination to re-“break” Jigidi’s shuffler, but on the rare ocassions I’ve needed to solve a Jigidi, I’ve come up with a technique that replaces a jigsaw’s pieces with ones that each show the row and column number they belong to, as well as colour-coding the rows and columns and drawing horizontal and vertical bars to help visual alignment. It makes the process significantly less-painful. It’s still pretty buggy code though and I end up tweaking it each and every time I use it, but it certainly works and makes jigsaws that lack clear visual markers (e.g. large areas the same colour) a lot easier.

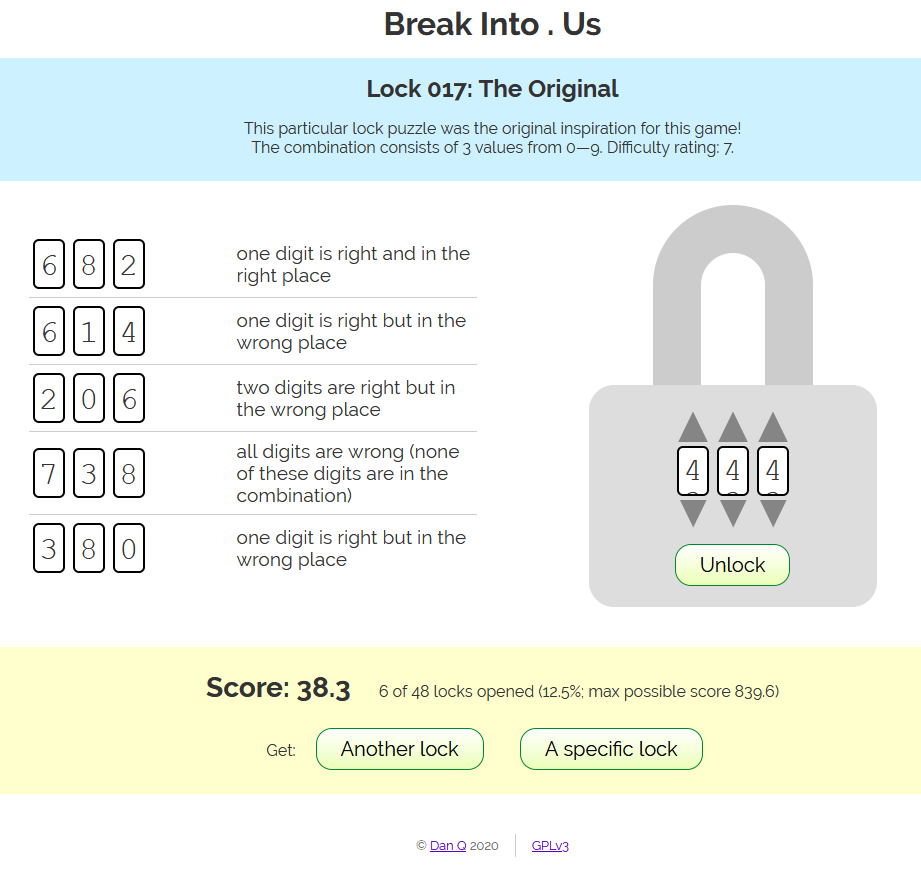

Break Into . Us (lock puzzle game)

I’ve made a puzzle game about breaking open padlocks. If you just want to play the game, go play the game. Or read on for the how-and-why of its creation.

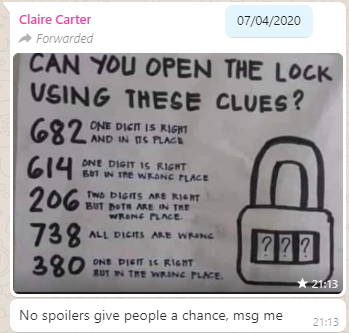

About three months ago, my friend Claire, in a WhatsApp group we both frequent, shared a brainteaser:

The puzzle was to be interpreted as follows: you have a three-digit combination lock with numbers 0-9; so 1,000 possible combinations in total. Bulls and Cows-style, a series of clues indicate how “close” each of several pre-established “guesses” are. In “bulls and cows” nomenclature, a “bull” is a correctly-guessed digit in the correct location and a “cow” is a correctly-guessed digit in the wrong location, so the puzzle’s clues are:

- 682 – one bull

- 614 – one cow

- 206 – two cows

- 738 – no bulls, no cows

- 380 – one cow

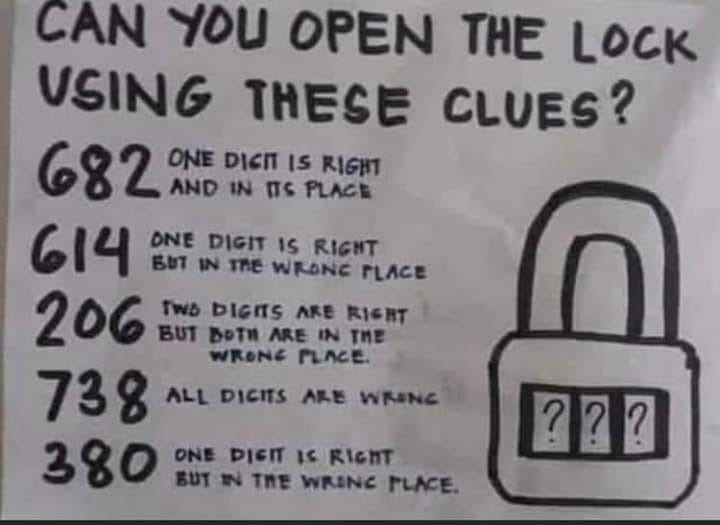

By the time I’d solved her puzzle the conventional way I was already interested in the possibility of implementing a general-case computerised solver for this kind of puzzle, so I did. My solver uses a simple “brute force” technique, as follows:

- Put all possible combinations into a search space.

- For each clue, remove from the search space all invalid combinations.

- Whatever combination is left is the correct answer.

Visualising the solver as a series of bisections of a search space got me thinking about something else: wouldn’t this be a perfectly reasonable way to programatically generate puzzles of this type, too? Something like this:

- Put all possible combinations into a search space.

- Randomly generate a clue such that the search space is bisected (within given parameters to ensure that neither too many nor too few clues are needed)

- Repeat until only one combination is left

Interestingly, this approach is almost the opposite of what a human would probably do. A human, tasked with creating a puzzle of this sort, would probably choose the answer first and then come up with clues that describe it. Instead, though, my solution would come up with clues, apply them, and then see what’s left-over at the end.

I expanded my generator to go beyond simple bulls-or-cows clues: it’s also capable of generating clues that make reference to the balance of odd and even digits (in a numeric lock), the number of different digits used in the combination, the sum of the digits of the combination, and whether or not the correct combination “ascends” or “descends”. I’ve ideas for other possible clue types too, which could be valuable to make even tougher combination locks: e.g. specifying how many numbers in the combination are adjacent to a consecutive number, specifying the types of number that the sum of the digits adds to (e.g. “the sum of the digits is a prime number”) and so on.

Next up, I wanted to make a based interface so that people could have a go at the puzzles in their web browser, track their progress through the levels, get a “score” based on the number and difficulty of the locks that they’d cracked (so they can compare it to their friends), and save their progress to carry on next time.

I implemented in pure vanilla HTML, CSS, SVG and JS, with no dependencies. Compressed, it delivers to your browser and is ready-to-play in a little under 10kB, most of which is the puzzles themselves (which are pregenerated and stored in a JSON file). Naturally, it lends itself well to running offline, so it’s PWA-enhanced with a service worker so it can be “installed” onto your device, too, and it’ll check for bonus puzzles and other updates periodically.

Honestly, the hardest bit of implementing the frontend was the “spinnable” digits: depending on your browser, these are an endless-scrolling <ul> implemented mostly in CSS and with snap points set, and then some JS to work out “what you meant” based on where you span to. Which feels like the right way to implement such a thing, but was a lot more work than putting together my own control, not least because of browser inconsistencies in the implementation of snap points.

Anyway: you should go and play the game, now, and let me know what you think. Is it worth expanding and improving? Should I leave it as it is? I’m open to ideas (and if you don’t like that I’m not implementing your suggestions, you can always fork a copy of the code and change it yourself)!

Or if you’d like to see some of the other JavaScript experiments I’ve done, you might enjoy my “cheating” hangman game, my recreation of the lunar lander game I wrote in college, or rediscover that time I was ill and came up the worst conceivable tool to calculate Pi.

![A notebook is held in front of terminal output. The terminal begins with 'Start position: [0,4]' and then shows a series of 5×5 grids containing numbers: one, labelled 'Route:', shows random grid of the numbers 0 through 24; the second, labelled 'Puzzle:', contains 1s, 2s, and 3s, corresponding perhaps to the orthagonal distances between consecutive numbers from the first grid; the third, whose title is obscured by the notebook, shows the same thing again but with 'walls' drawn in ASCII art between some of the numbers. The notebook in front contains hand-drawn sketches of similar grids with arrows "jumping" around between them.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2025/03/20250313_100059-640x487.jpg)