Today, I can overhear the two guys who are digging a trench through my garden.

Guy 1: Does this look like a gas pipe to you?

Guy 2: Dunno. But we can’t dig round it soo…

😬

Today, I can overhear the two guys who are digging a trench through my garden.

Guy 1: Does this look like a gas pipe to you?

Guy 2: Dunno. But we can’t dig round it soo…

😬

I decided to take my meeting with my coach today in our house’s new library, which my metamour JTA has recently been working hard on decorating, constructing, and filling with books. The room’s not quite finished, but it made for a brilliant space for a bit of quiet reflection and self-growth work.

(Incidentally: I might be treating “lives in a house with a library” as a measure of personal success. Like: this is what winning at life looks like, right? Because whatever else goes wrong, at least you can go hide in the library!)

There are two particular varieties of email address that I don’t often see, but I’ve been known to ridicule when I have:

OurHouseName@example.com. These always seemed to me to undermine one of the

single-best things about an email address compared to postal mail – that they don’t change when you move house!1

MrAndMrsSmith@example.net. These make me want to scream “You know email addresses are basically

free, right? You don’t have to share one!” Even back when most people got their email address directly from their dial-up provider, most ISPs offered some number of addresses (e.g. five).

If you’ve come across either of the above before, there’s… perhaps a reasonable chance that it was in the possession of somebody born before 1960 (and the older, the more-likely)2.

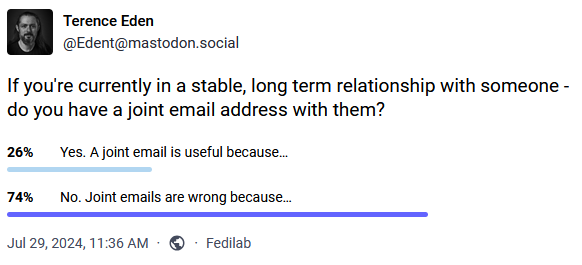

I found myself thinking about this as I clicked the “No” button on a poll by Terence Eden that asked whether I used a “shared” email address when in a stable long-term relationship.

It wasn’t until after I clicked “No” that I realised that, in actual fact, I have had multiple email addresses that I’ve share with significant other(s). And more than that, sometimes they’ve been geographically-based! What’s going on?

I’ve routinely had domains or subdomains that I’ve used to represent a place that I live. They’re convenient for when you want to give somebody a short web address which’ll take them to a page with directions to you and links to your location in a variety of different services and formats.

And by that point, you might as well have an email alias, e.g. all@myhouse.example.org, that forwards on email to, well, all the adults at the house. What I’ve

described there is, after a fashion, a shared email address tied to a geographical location. But we don’t ever send anything from it. Nor do we use it for any kind of

personal communication with anybody outside the house.

We don’t give out these all@ addresses (or their aliases: every company gets their own) to people willy-nilly. But they’re useful for shared services that send

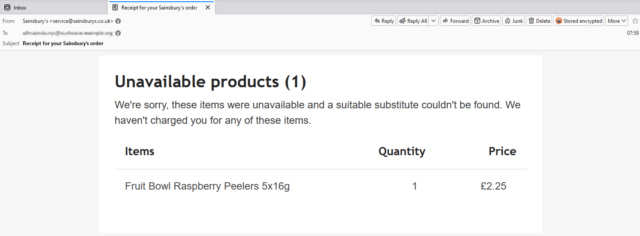

automated emails to us all. For example:

Sure, the need for most of these solutions would evaporate instantly if more services supported multi-user or delegated access3. But outside of that fantasy world, shared aliases seem to be pretty useful!

1 The most ill-conceived example of geographically-based email addresses I’ve ever seen

came from a a 2003 proposal by then-MP Derek Wyatt, who proposed that the domain name part of every single email address should contain not

only the country of the owner (e.g. .uk) but also their complete postcode. He was under the delusion that this would somehow prevent spam. Even ignoring the

immense technical challenges of his proposal and the impossibility of policing it across the borders of every country that uses email… it probably wouldn’t even be

effective at his stated goal. I’ll let The Register take it from here.

2 No ageism intended: I suspect that the phenomenon actually stems from the fact that as email took off in the noughties this demographic who were significantly more-likely than younger folks to have (a) a very long-term home that they didn’t anticipate moving out of any time soon, and (b) an existing anticipation that people and companies wrote to them as a couple, not individually.

3 I’d love it if the grocery delivery sites would let multiple “accounts”, by mutual consent, share a delivery slot, destination, and payment method. It’d be cool to know that we could e.g. have a houseguest and give them temporary access to a specific order that was scheduled for during their stay. But that’s probably a lot of work for very little payoff if you’re busy running a supermarket.

As our house rennovations/attic conversions come to a close, I found myself up in what will soon become my en suite, fitting a mirror, towel rail, and other accessories.

Wanting to minimise how much my power tool usage disturbed the rest of the house, I went to close the door separating my new bedroom from my rest of my house, only to find that it didn’t properly fit its frame and instead jammed part-way-closed.

Somehow we’d never tested that this door closed properly before we paid the final instalment to the fitters. And while I’m sure they’d have come back to repair the problem if I asked, I figured that it’d be faster and more-satisfying to fix it for myself.

As a result of an extension – constructed long before we moved in – the house in Preston in which spent much of my childhood had not just a front and a back door but what we called the “side door”, which connected the kitchen to the driveway.

Unfortunately the door that was installed as the “side door” was really designed for interior use and it suffered for every winter it faced the biting wet North wind.

My father’s DIY skills could be rated as somewhere between mediocre and catastrophic, but his desire to not spend money “frivolously” was strong, and so he never repaired nor replaced the troublesome door. Over the course of each year the wood would invariably absorb more and more water and swell until it became stiff and hard to open and close.

The solution: every time my grandfather would visit us, each Christmas, my dad would have his dad take down the door, plane an eighth of an inch or so off the bottom, and re-hang it.

Sometimes, as a child, I’d help him do so.

The first thing to do when repairing a badly-fitting door is work out exactly where it’s sticking. I borrowed a wax crayon from the kids’ art supplies, coloured the edge of the door, and opened and closed it a few times (as far as possible) to spot where the marks had smudged.

Fortunately my new bedroom door was only sticking along the top edge, so I could get by without unmounting it so long as I could brace it in place. I lugged a heavy fence post rammer from the garage and used it to brace the door in place, then climbed a stepladder to comfortably reach the top.

After my paternal grandfather died, there was nobody left who would attend to the side door of our house. Each year, it became a little stiffer, until one day it wouldn’t open at all.

Surely this would be the point at which he’d pry open his wallet and pay for it to be replaced?

Nope. Instead, he inexpertly screwed a skirting board to it and declared that it was now no-longer a door, but a wall.

I suppose from a functionalist perspective he was correct, but it still takes a special level of boldness to simply say “That door? It’s a wall now.”

Of all the important tasks a carpenter (or in this case, DIY-er) must undertake, hand sanding must surely be the least-satisfying.

But reaching the end of the process, the feel of a freshly-planed, carefully-sanded piece of wood is fantastic. This surface represented chaos, and now it represents order. Order that you yourself have brought about.

Often, you’ll be the only one to know. When my grandfather would plane and sand the bottom edge of our house’s side door, he’d give it a treatment of oil (in a doomed-to-fail attempt to keep the moisture out) and then hang it again. Nobody can see its underside once it’s hung, and so his handiwork was invisible to anybody who hadn’t spent the last couple of months swearing at the stiffness of the door.

Even though the top of my door is visible – particularly visible, given its sloping face – nobody sees the result of the sanding because it’s hidden beneath a layer of paint.

A few brush strokes provide the final touch to a spot of DIY… that in provided a framing device for me to share a moment of nostalgia with you.

Sweep away the wood shavings. Keep the memories.

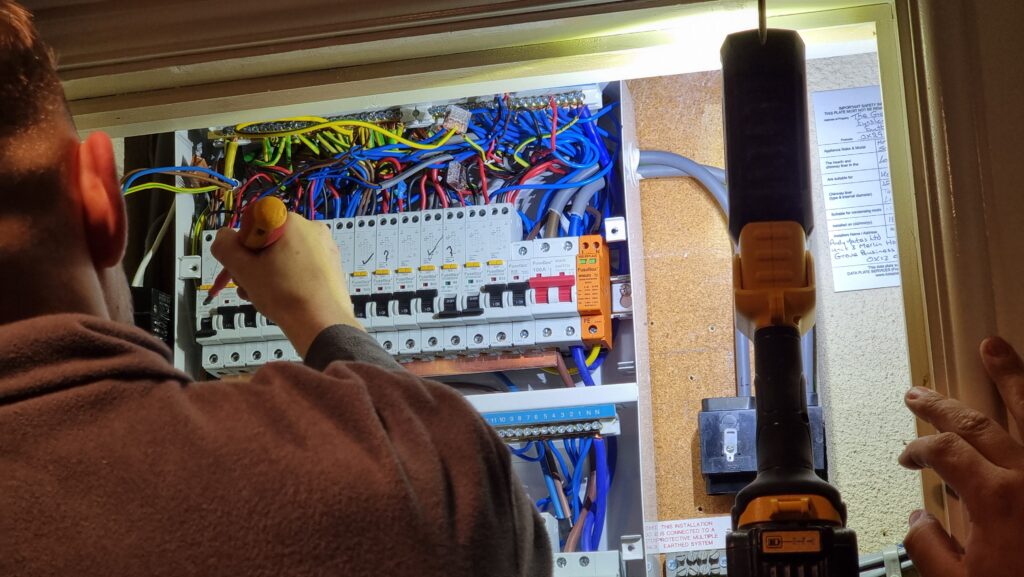

This week, I received a ~240V AC electric shock. I can’t recommend it.

We’re currently having our attic converted, so we’ve had some electricians in doing the necessary electrical wiring. Shortly after they first arrived they discovered that our existing electrics were pretty catastrophic, and needed to make a few changes including a new fusebox and disconnecting the hilariously-unsafe distribution board in the garage.

After connecting everything new up they began switching everything back on and testing the circuits… and we were surprised to hear arcing sounds and see all the lights flickering.

The electricians switched everything off and started switching breakers back on one at a time to try to identify the source of the fault, reasonably assuming that something was shorting somewhere, but no matter what combination of switches were enabled there always seemed to be some kind of problem.

Noticing that the oven’s clock wasn’t just blinking 00:00 (as it would after a power cut) but repeatedly resetting itself to 00:00, I pointed this out to the electricians as an indicator that the problem was occurring on their current permutation of switches, which was strange because it was completely different to the permutation that had originally exhibited flickering lights.

I reached over to point at the oven, and the tip of my finger touched the metal of its case…

Blam! I felt a jolt through my hand and up my arm and uncontrollably leapt backwards across the room, convulsing as I fell to the floor. I gestured to the cooker and shouted something about it being live, and the electricians switched off its circuit and came running with those clever EM-field sensor pens they use.

Somehow the case of the cooker was energised despite being isolated at the fusebox? How could that be?

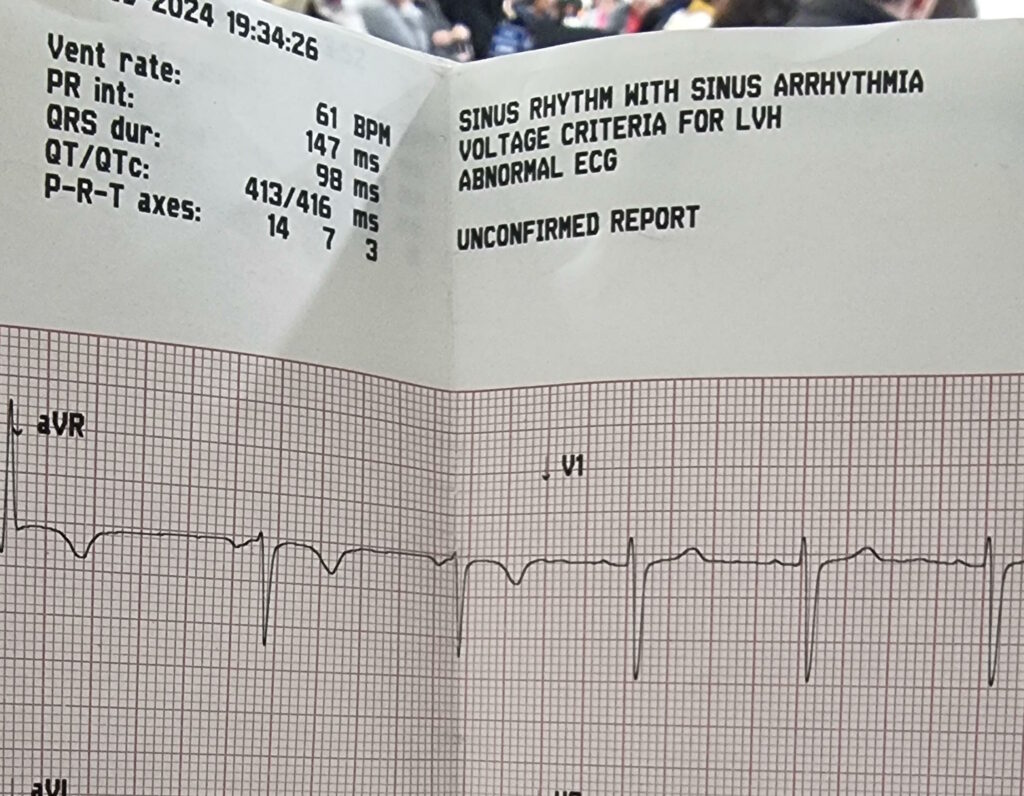

I missed the next bits of the diagnosis of our electrical system because I was busy getting my own diagnosis: it turns out that if you get a mains electric shock – even if you’re conscious and mobile – the NHS really want you to go to A&E.

At my suggestion, Ruth delivered me to the Minor Injuries unit at our nearest hospital (I figured that what I had wasn’t that serious, and the local hospital generally has shorter wait times!)… who took one look at me and told me that I ought to be at the emergency department of the bigger hospital over the way.

Off at the “right” hospital I got another round of ECG tests, some blood tests (which can apparently be used to diagnose muscular damage: who knew?), and all the regular observations of pulse and blood pressure and whatnot that you might expect.

And then, because let’s face it I was probably in better condition than most folks being dropped off at A&E, I was left to chill in a short stay ward while the doctors waited for test results to come through.

Meanwhile, back at home our electricians had called-in SSEN, who look after the grid in our area. It turns out that the problem wasn’t directly related to our electrical work at all but had occurred one or two pylons “upstream” from our house. A fault on the network had, from the sounds of things, resulted in “live” being sent down not only the live wire but up the earth wire too.

That’s why appliances in the house were energised even with their circuit breakers switched-off: they were connected to an earth that was doing pretty-much the opposite of what an earth should: discharging into the house!

It seems an inconceivable coincidence to me that a network fault might happen to occur during the downtime during which we happened to have electricians working, so I find myself wondering if perhaps the network fault had occurred some time ago but only become apparent/dangerous as a result of changes to our household configuration.

I’m no expert, but I sketched a diagram showing how such a thing might happen (click to embiggen). I’ll stress that I don’t know for certain what went wrong: I’m just basing this on what I’ve been told my SSEN plus a little speculation:

By the time I was home from the hospital the following day, our driveway was overflowing with the vehicles of grid engineers to the point of partially blocking the main street outside (which at least helped ensure that people obeyed our new 20mph limit for a change).

Two and a half days later, I’m back at work and mostly recovered. I’ve still got some discomfort in my left hand, especially if I try to grip anything tightly, but I’m definitely moving in the right direction.

It’s actually more-annoying how much my chest itches from having various patches of hair shaved-off to make it possible to hook up ECG electrodes!

Anyway, the short of it is that I recommend against getting zapped by the grid. If it had given me superpowers it might have been a different story, but I guess it just gave me sore muscles and a house with a dozen non-working sockets.

I was told Windows installation should take less than 20 minutes, but these ones have been sitting outside my house all day while the builders sit on the roof and listen to the radio. Do I need a faster processor? #TechSupport

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What do you complain about the most?

I’m British. So I complain about very little. Instead, I tut loudly to myself.

But the thing that makes me tut the loudest, perhaps, is when I discover that somebody has put a roll of toilet paper on its holder the wrong way.

I’m aware that there are some people who do not hold a strong opinion on the correct orientation of a horizontally-mounted roll of toilet paper. That’s fine; not everybody has to care about these things. Maybe you’ll be persuaded that there’s a “right” way by this post (and there is), but if not, no problem.

But for the anybody who deliberately and consciously hangs toilet paper the wrong way… here’s why you’re mistaken:

I share a home with a wrong-way hanger, but about 13 years ago we came to a household agreement: I’d quietly “correct” any incorrectly-installed toilet rolls in shared bathrooms1, and nobody would deliberately switch them back2, and in exchange I’d refrain from trying to educate people about why they were wrong.3

(While researching this article, I was pleased to discover that no major emoji font depicts a toilet roll in the wrong orientation. 🧻🎉)

1 A man can do whatever the hell he likes in the comfort of his own en suite.

2 This clause was added after it became apparent that our then-housemate Paul decided it’d be a fun prank to go around the house reversing my corrections (not because he preferred the wrong way, but just to troll me!). Which I can admit was a fun prank… until I challenged him on it and he denied it, at which point it became gaslighting.

3 This doesn’t count as forcing an education on my household. My blog isn’t in your face: you can skip it any time you want. You can even lie and say you read it when you don’t; I won’t know, especially this month when I’ve been writing so prolifically – now on my longest-ever daily streak! – that I probably won’t even remember what I wrote about.

Almost a decade ago I shared a process that my domestic polyfamily and I had been using (by then, for around four years) to manage our household finances. That post isn’t really accurate any more, so it’s time for an update (there’s a link if you just want the updated spreadsheet):

For my examples below, assume a three-person family. I’m using unrealistic numbers for easy arithmetic.

We’ve never done things this way, but for completeness sake I’ll mention it: the simplest way that households can split their costs is by dividing them between the participants equally: if the family make a £60 shopping trip, £20 should be paid by each of Alice, Bob, and Chris.

My example above shows exactly why this might not be a smart choice: this model would have each participant contribute £833.33 over the course of the month, which is more than Chris earned. If this month is representative, then Chris will gradually burn through their savings and go broke, while Alice will put over a grand into her savings account every month!

We’re a bunch of leftie socialist types, and wanted to reflect our political outlook in our household finances, too. So rather than just splitting our costs equally between us, we initially implemented a means-assessment system based on the relative differences between our incomes. The thinking was that somebody that earns twice as much should contribute twice as much towards the costs of running the household.

Using our example family above, here’s how that might look:

By analogy: The “Income-Assessed” model is functionally equivalent to splitting each and every expense according to the participants income – e.g. if a £100 bill landed on their doormat, Alice would pay £57, Bob £29, and Chris £14 of it – but has the convenience that everybody just pays for things “as they go along” and then square everything up when their paycheques come in.

Over time, our expenditures grew and changed and our incomes grew, but they didn’t do so in an entirely simple fashion, and we needed to make some tweaks to our income-assessed model of household finance contributions. For example:

Eventually, we came to see that what we were doing was trying to patch a partially-broken system, and tried something new!

In 2022, we transitioned to a same-residual system that attempts to share out out money in an even-more egalitarian way. Instead of each person contributing in accordance with their income, the model attempts to leave each person with the same average amount of disposable personal income at the end. The difference is most-profound where the relative incomes are most-diverse.

With the example family above, that would mean:

That’s a very different result than the Income-Assessed calculation came up with for the same family! Instead of Chris giving money to Alice and Bob, because those two contributed to household costs disproportionately highly for their relative incomes, Alice gives money to Bob and Chris, because their incomes (and expenditures) were much lower. Ignoring any non-household costs, all three would expect to have the same bank balance at the start of the month as at the end, after settlement.

By analogy: The “Same-Residual” model is functionally equivalent to having everybody’s salary paid into a shared bank account, out of which all household expenditures are paid, and at the end of the month everything that’s left in the bank account gets split equally between the participants.

We’ve made tweaks to this model, too, of course. For example: we’ve set a “target” residual and, where we spend little enough in a month that we would each be eligible for more than that, we instead sweep the excess into our family savings account. It’s a nice approach to help build up a savings reserve without feeling a pinch.

I’m sure our model will continue to evolve, as it has for the last decade and a half, but for now it seems stable, fair, and reasonable. Maybe it’ll work for your household too (whether or not you’re also a polyamorous family!): take a look at the spreadsheet in Google Drive and give it a go.

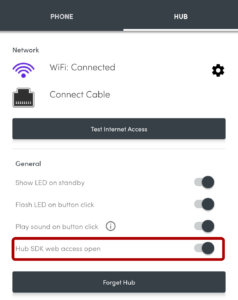

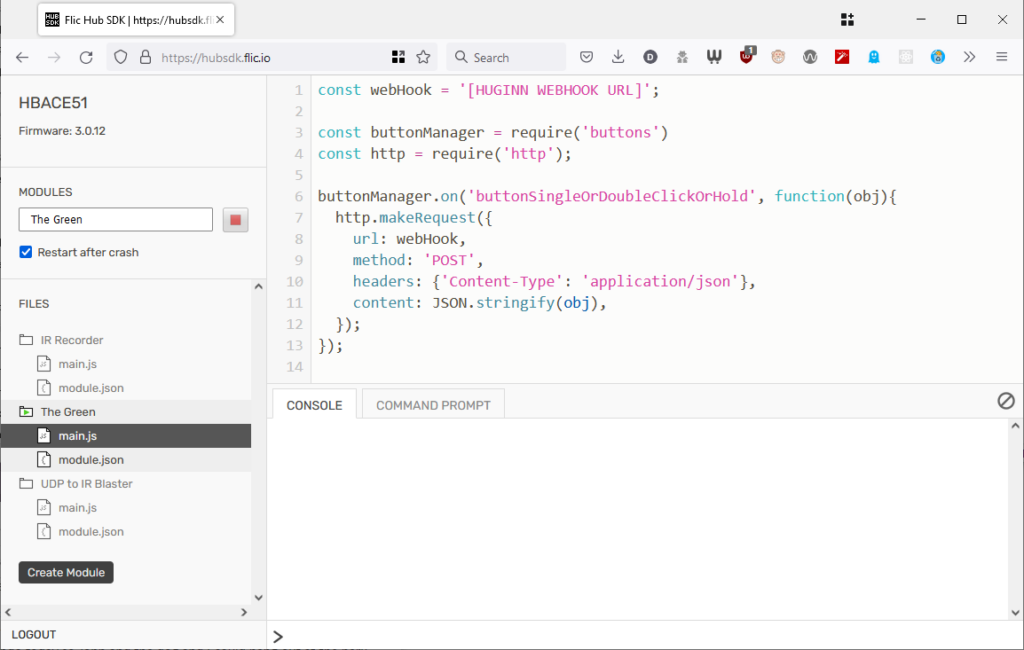

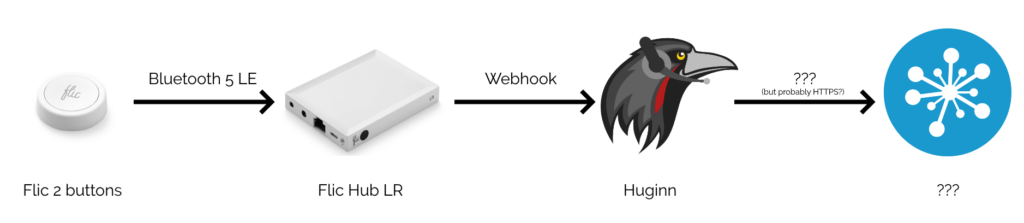

I’ve been playing with a Flic Hub LR and some Flic 2 buttons. They’re “smart home” buttons, but for me they’ve got a killer selling point: rather than locking you in to any particular cloud provider (although you can do this if you want), you can directly program the hub. This means you can produce smart integrations that run completely within the walls of your house.

Here’s some things I’ve been building:

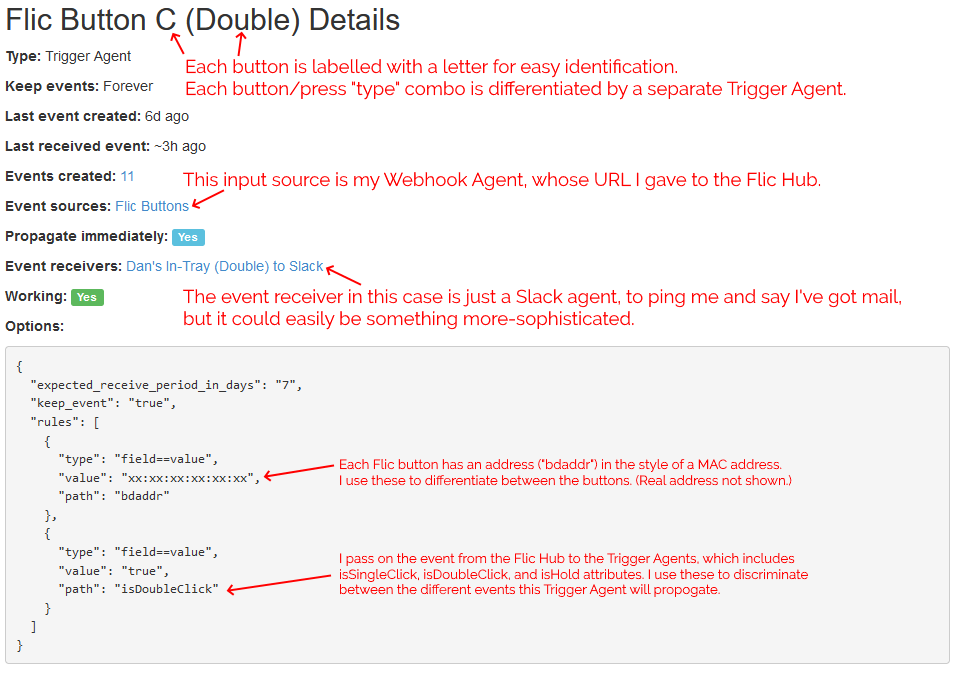

I run a Huginn instance on our household NAS. If you’ve not come across it before, Huginn is a bit like an open-source IFTTT: it’s got a steep learning curve, but it’s incredibly powerful for automation tasks. The first step, then, was to set up my Flic Hub LR to talk to Huginn.

This was pretty simple: all I had to do was switch on “Hub SDK web access open” for the hub using the Flic app, then use the the web SDK to add this script to the hub. Now whenever a button was clicked, double-clicked, or held down, my Huginn installation would receive a webhook ping.

For convenience, I have all button-presses sent to the same Webhook, and use Trigger Agents to differentiate between buttons and press-types. This means I can re-use functionality within Huginn, e.g. having both a button press and some other input trigger a particular action.

By our front door, we have “in trays” for each of Ruth, JTA and I, as well as one for the bits of Three Rings‘ post that come to our house. Sometimes post sits in the in-trays for a long time because people don’t think to check them, or don’t know that something new’s been added.

I configured Huginn with a Trigger Agent to receive events from my webhook and filter down to just single clicks on specific buttons. The events emitted by these triggers are used to notify in-tray owners.

In my case, I’ve got pings being sent to mail recipients via Slack, but I could equally well be integrating to other (or additional) endpoints or even performing some conditional logic: e.g. if it’s during normal waking hours, send a Pushbullet notification to the recipient’s phone, otherwise send a message to an Arduino to turn on an LED strip along the top of the recipient’s in-tray.

I’m keeping it simple for now. I track three kinds of events (click = “post in your in-tray”, double-click = “I’ve cleared my in-tray”, hold = “parcel wouldn’t fit in your in-tray: look elsewhere for it”) and don’t do anything smarter than send notifications. But I think it’d be interesting to e.g. have a counter running so I could get a daily reminder (“There are 4 items in your in-tray.”) if I don’t touch them for a while, or something?

Following the same principle, and with the hope that the Flic buttons are weatherproof enough to work in a covered outdoor area, I’ve fitted one… to the top of the box our milkman delivers our milk into!

Most mornings, our milkman arrives by 7am, three times a week. But some mornings he’s later – sometimes as late as 10:30am, in extreme cases. If he comes during the school run the milk often gets forgotten until much later in the day, and with the current weather that puts it at risk of spoiling. Ironically, the box we use to help keep the milk cooler for longer on the doorstep works against us because it makes the freshly-delivered bottles less-visible.

I’m yet to see if the milkman will play along and press the button when he drops off the milk, but if he does: we’re set! A second possible bonus is that the kids love doing anything that allows them to press a button at the end of it, so I’m optimistic they’ll be more-willing to add “bring in the milk” to their chore lists if they get to double-click the button to say it’s been done!

I’m still playing with ideas for the next round of buttons. Could I set something up to streamline my work status, so my colleagues know when I’m not to be disturbed, away from my desk, or similar? Is there anything I can do to simplify online tabletop roleplaying games, e.g. by giving myself a desktop “next combat turn” button?

I’m quite excited by the fact that the Flic Hub can interact with an infrared transceiver, allowing it to control televisions and similar devices: I’d love to be able to use the volume controls on our media centre PC’s keyboard to control our TV’s soundbar: and because the Flic Hub can listen for UDP packets, I’m hopeful that something as simple as AutoHotkey can make this possible.

Or perhaps I could make a “universal remote” for our house, accessible as a mobile web app on our internal Intranet, for those occasions when you can’t even be bothered to stand up to pick up the remote from the other sofa. Or something that switched the TV back to the media centre’s AV input when consoles were powered-down, detected by their network activity? (Right now the TV automatically switches to the consoles when they’re powered-on, but not back again afterwards, and it bugs me!)

It feels like the only limit with these buttons is my imagination, and that’s awesome.

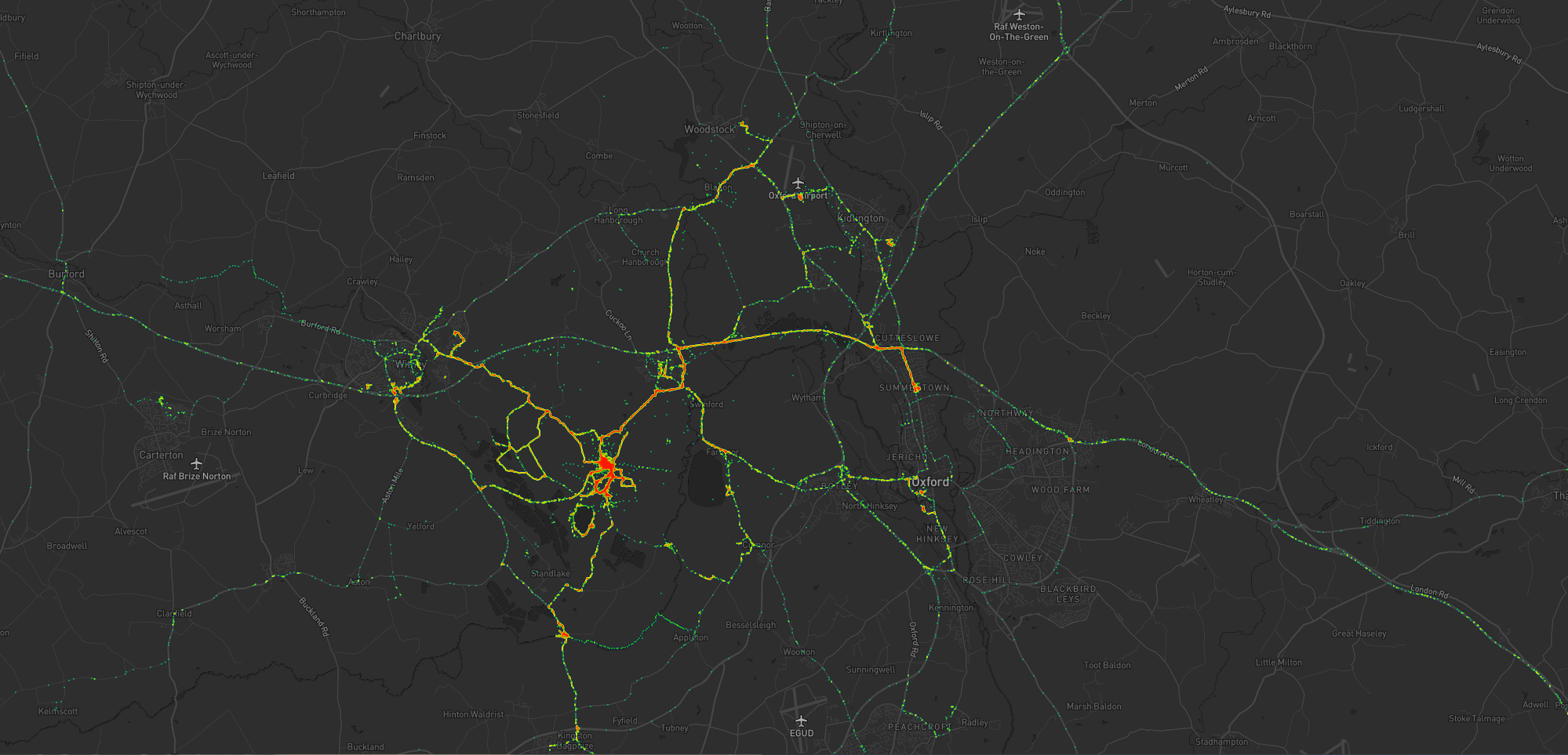

As I mentioned last year, for several years I’ve collected pretty complete historic location data from GPSr devices I carry with me everywhere, which I collate in a personal μlogger server.

Going back further, I’ve got somewhat-spotty data going back a decade, thanks mostly to the fact that I didn’t get around to opting-out of Google’s location tracking until only a few years ago (this data is now also housed in μlogger). More-recently, I now also get tracklogs from my smartwatch, so I’m managing to collate more personal location data than ever before.

Inspired perhaps at least a little by Aaron Parecki, I thought I’d try to do something cool with it.

What you’re looking at is a heatmap showing my location over the last year or so since I moved to The Green. Between the pandemic and switching a few months prior to a job that I do almost-entirely at home there’s not a lot of travel showing, but there’s some. Points of interest include:

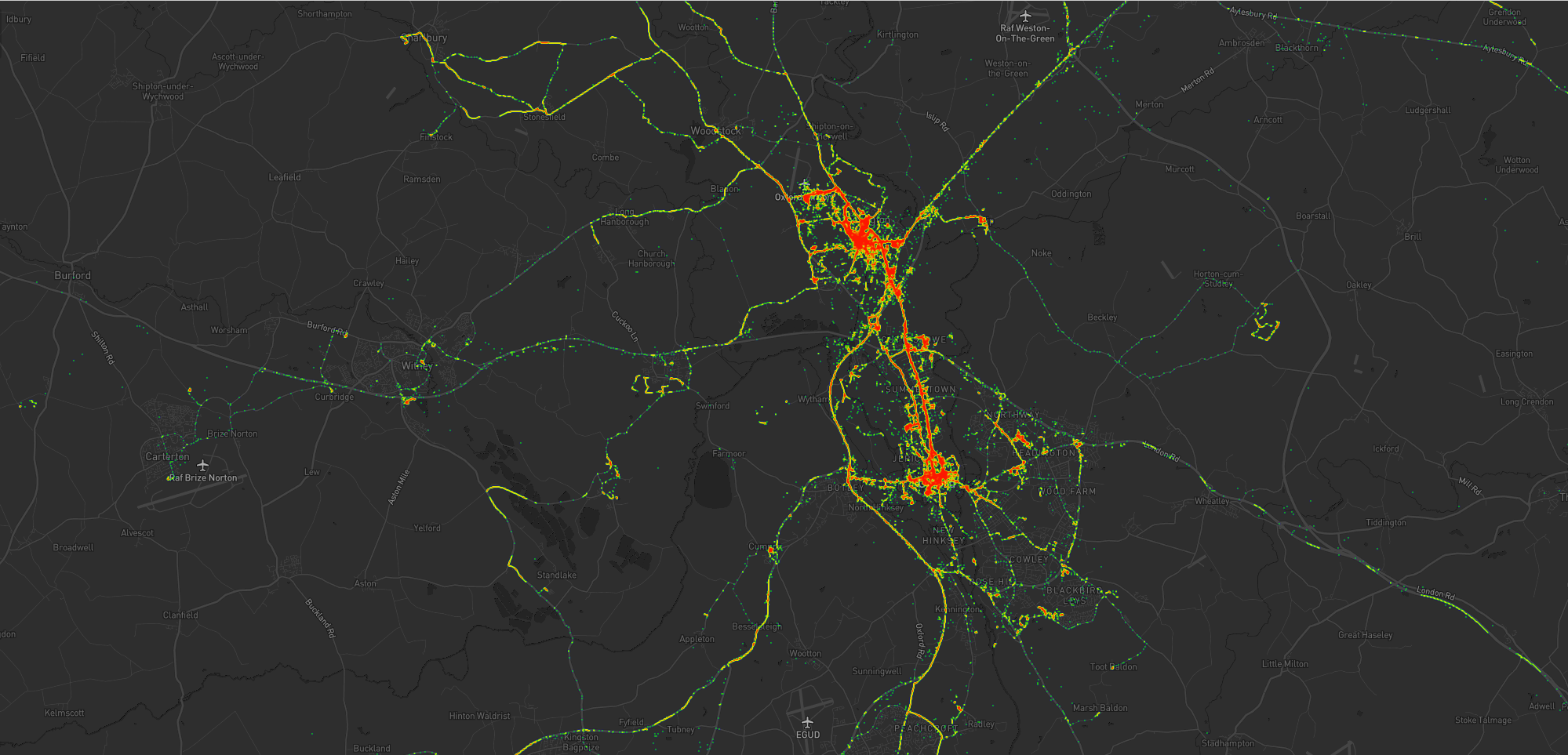

Let’s go back to the 7 years prior, when I lived in Kidlington. This paints a different picture:

This heatmap highlights some of the ways in which my life was quite different. For example:

Let’s go back further:

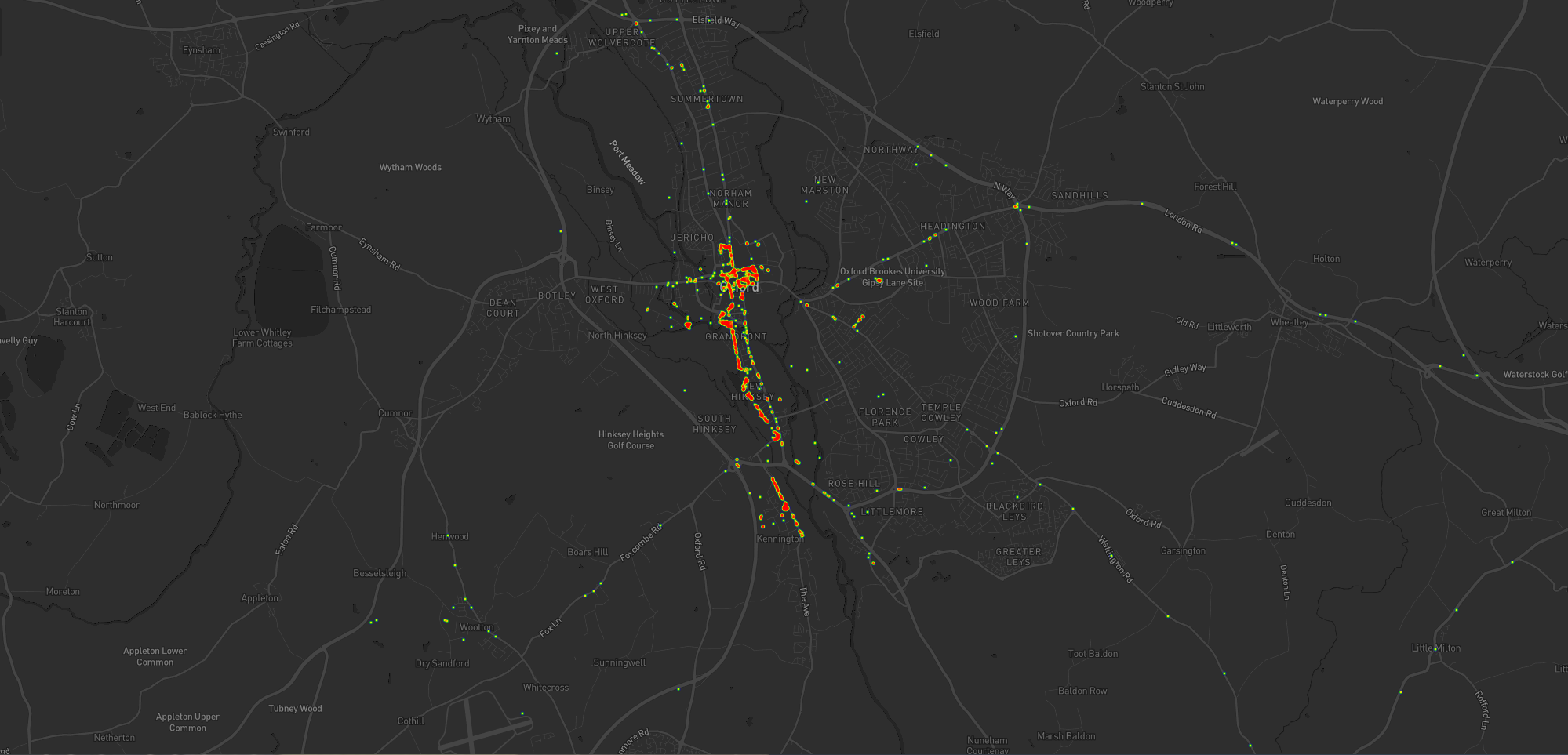

Before 2011, and before we bought our first house, I spent a couple of years living in Kennington, to the South of Oxford. Looking at this heatmap, you’ll see:

I really love maps, and I love the fact that these heatmaps are capable of painting a picture of me and what my life was like in each of these three distinct chapters of my life over the last decade. I also really love that I’m able to collect and use all of the personal data that makes this possible, because it’s also proven useful in answering questions like “How many times did I visit Preston in 2012?”, “Where was this photo taken?”, or “What was the name of that place we had lunch when we got lost during our holiday in Devon?”.

There’s so much value in personal geodata (that’s why unscrupulous companies will try so hard to steal it from you!), but sometimes all you want to do is use it to draw pretty heatmaps. And that’s cool, too.

I have a μlogger instance with the relevant positional data in. I’ve automated my process, but the essence of it if you’d like to try it yourself is as follows:

First, write some SQL to extract all of the position data you need. I round off the latitude and longitude to 5 decimal places to help “cluster” dots for frequency-summing, and I raise the frequency to the power of 3 to help make a clear gradient in my heatmap by making hotspots exponentially-brighter the more popular they are:

SELECT ROUND(latitude, 5) lat, ROUND(longitude, 5) lng, POWER(COUNT(*), 3) `count` FROM positions WHERE `time` BETWEEN '2020-06-22' AND '2021-08-22' GROUP BY ROUND(latitude, 5), ROUND(longitude, 5)

This data needs converting to JSON. I was using Ruby’s mysql2 gem to

fetch the data, so I only needed a .to_json call to do the conversion – like this:

db = Mysql2::Client.new(host: ENV['DB_HOST'], username: ENV['DB_USERNAME'], password: ENV['DB_PASSWORD'], database: ENV['DB_DATABASE']) db.query(sql).to_a.to_json

Approximately following this guide and leveraging my Mapbox

subscription for the base map, I then just needed to include leaflet.js, heatmap.js, and leaflet-heatmap.js before writing some JavaScript code

like this:

body.innerHTML = '<div id="map"></div>'; let map = L.map('map').setView([51.76, -1.40], 10); // add the base layer to the map L.tileLayer('https://api.mapbox.com/styles/v1/{id}/tiles/{z}/{x}/{y}?access_token={accessToken}', { maxZoom: 18, id: 'itsdanq/ckslkmiid8q7j17ocziio7t46', // this is the style I defined for my map, using Mapbox tileSize: 512, zoomOffset: -1, accessToken: '...' // put your access token here if you need one! }).addTo(map); // fetch the heatmap JSON and render the heatmap fetch('heat.json').then(r=>r.json()).then(json=>{ let heatmapLayer = new HeatmapOverlay({ "radius": parseFloat(document.querySelector('#radius').value), "scaleRadius": true, "useLocalExtrema": true, }); heatmapLayer.setData({ data: json }); heatmapLayer.addTo(map); });

That’s basically all there is to it!

This week, with help from Robin and JTA, I built a TropicTemple Tall XXL climbing frame in the garden of our new house. Manufacturer Fatmoose provided us with a pallet-load of lumber and a sack of accessories, delivered to our driveway, based on a design Ruth and I customised using their website, and we assembled it on-site over the course of around three days. The video above is a timelapse taken from our kitchen window using a tablet I set up for that purpose, interspersed with close-up snippets of us assembling it and of the children testing it out.

I’ve also built a Virtual Tour so you can explore the playframe using your computer, phone, or VR headset. Take a look!

The video is also available via:

This week, some colleagues at Automattic and I are sharing pictures of our workspaces. So I made a 360° panoramic with interactive “info points” (apologies for work-specific jargon). Would you like to see it?

Seven years ago, I wrote a six-part blog series (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) about our Ruth, JTA and I’s experience of buying our first house. Now, though, we’re moving again, and it’s brought up all the same kinds of challenges and stresses as last time, plus a whole lot of bonus ones to boot.

In particular, new challenges this time around have included:

But it’s finally all coming together. We’ve got a house full of boxes, mind, and we can’t find anything, and somehow it still doesn’t feel like we’re prepared for when the removals lorry comes later this week. But we’re getting there. After a half-hour period between handing over the keys to the old place and picking up the keys to the new place (during which I guess we’ll technically be very-briefly homeless) we’ll this weekend be resident in our new home.

Our new house will:

We lose some convenient public transport links, but you can’t have everything. And with me working from home all the time, Ruth – like many software geeks – likely working from home for the foreseeable future (except when she cycles into work), and JTA working from home for now but probably returning to what was always a driving commute “down the line”, those links aren’t as essential to us as they once were.

Sure: we’re going to be paying for it for the rest of our lives. But right now, at least, it feels like what we’re buying is a house we could well live in for the rest of our lives, too.

I certainly hope so. Moving house is hard.

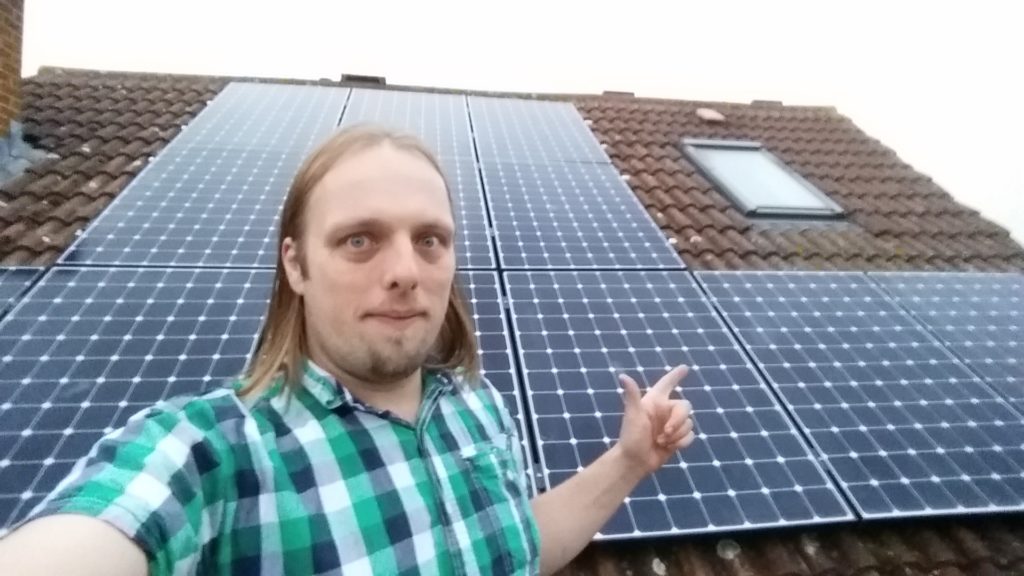

One of the great joys of owning a house is that you can do pretty much whatever you please with it. I celebrated Ruth, JTA and I’s purchase of Greendale last year by wall-mounting not one but two televisions and putting shelves up everywhere. But honestly, a little bit of DIY isn’t that unusual nor special. We’ve got plans for a few other changes to the house, but right now we’re pushing our eco-credentials: we had cavity wall insulation added to the older parts of the building the other week and an electric car charging port added not long before that. And then… came this week’s big change.

Solar photovoltaics! They’re cool, they’re (becoming) economical, and we’ve got this big roof that faces almost due-South that would otherwise be just sitting there catching rain. Why not show off our green credentials and save ourselves some money by covering it with solar cells, we thought.

Because it’s me, I ended up speaking to five different companies and, after removing one from the running for employing a snake for a salesman, collecting seven quotes from the remaining four, I began to do my own research. The sheer variety of panels, inverters, layouts and configurations (all of which are described in their technical sheets using terms that in turn required a little research into electrical efficiency and dusting off formulas I’d barely used since my physics GCSE exam) are mind-boggling. Monolithic, string, or micro-inverters? 250w or 327w panels? Where to run the cables that connect the inverter (in the attic) to the generation meter and fusebox (in the ground floor toilet)? Needless to say, every company had a different idea about the “best way” to do it – sometimes subtly different, sometimes dramatically – and had a clear agenda to push. So – as somebody not suckered in to a quick deal – I went and did the background reading first.

In case you’re not yet aware, let me tell you the three reasons that solar panels are a great idea, economically-speaking. Firstly, of course, they make electricity out of sunlight which you can then use: that’s pretty cool. With good discipline and a monitoring tool either in hardware or software, you can discover the times that you’re making more power than you’re using, and use that moment to run the dishwasher or washing machine or car charger or whatever. Or the tumble drier, I suppose, although if you’re using the tumble drier because it’s sunny then you lose a couple of your ‘green points’ right there. So yeah: free energy is a nice selling point.

The second point is that the grid will buy the energy you make but don’t use. That’s pretty cool, too – if it’s a sunny day but there’s nobody in the house, then our electricity meter will run backwards: we’re selling power back to the grid for consumption by our neighbours. Your energy provider pays you for that, although they only pay you about a third of what you pay them to get the energy back again if you need it later, so it’s always more-efficient to use the power (if you’ve genuinely got something to use it for, like ad-hoc bitcoin mining or something) than to sell it. That said, it’s still “free money”, so you needn’t complain too much.

The third way that solar panels make economic sense is still one of the most-exciting, though. In order to enhance uptake of solar power and thus improve the chance that we hit the carbon emission reduction targets that Britain committed to at the Kyoto Protocol (and thus avoid a multi-billion-pound fine), the government subsidises renewable microgeneration plants. If you install solar panels on your house before the end of this year (when the subsidy is set to decrease) the government will pay you 14.38p per unit of electricity you produce… whether you use it or whether you sell it. That rate is retail price index linked and guaranteed for 20 years, and as a result residential solar installations invariably “pay for themselves” within that period, making them a logical investment for anybody who’s got a suitable roof and who otherwise has the money just sitting around. (If you don’t have the cash to hand, it might be worth taking out a loan to pay for solar panels, but then the maths gets a lot more complicated.)

The scaffolding went up on the afternoon of day one, and I took the opportunity to climb up myself and give the gutters a good cleaning-out, because it’s a lot easier to do that from a fixed platform than it is from our wobbly “community ladder”. On day two, a team of electricians and a solar expert appeared at breakfast time and by 3pm they were gone, leaving behind a fully-functional solar array. On day three, we were promised that the scaffolding company would reappear and remove the climbing frame from our garden, but it’s now dark and they’ve not been seen yet, which isn’t ideal but isn’t the end of the world either: not least because Ruth’s been unwell and thus hasn’t had the chance to get up and see the view from the top of it, yet.

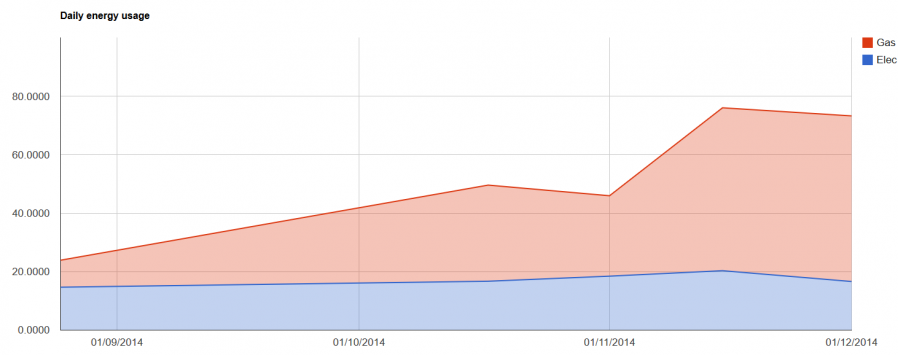

We made about 4 units of electricity on our first day, which didn’t seem bad for an overcast afternoon about a fortnight away from the shortest day of the year. That’s about enough to power every light bulb in the house for the duration that the sun was in the sky, plus a little extra (we didn’t opt to commemorate the occasion by leaving the fridge door open in order to ensure that we used every scrap of the power we generated).

Because I’m a bit of a data nerd these years, I’ve been monitoring our energy usage lately anyway and as a result I’ve got an interesting baseline against which to compare the effectiveness of this new addition. And because there’s no point in being a data nerd if you don’t get to share the data love, I will of course be telling you all about it as soon as I know more.