At the very end of last year, right before the subsidy rate dropped in January, I had solar panels installed: you may remember that I blogged about it at the time. I thought you might be interested to know how that’s working out for us.

Because I’m a data nerd, I decided to monitor our energy usage, production, and total cost in order to fully understand the economic impact of our tiny power station. I appreciate that many of you might not be able to appreciate how cool this kind of data is, but that’s because you don’t have as good an appreciation of how fun statistics can be… it is cool, damn it!

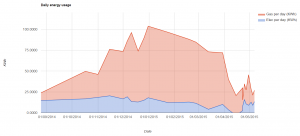

If you look at the chart above, for example (click for a bigger version), you’ll notice a few things:

- We use a lot more KWh of gas than electricity (note that’s not units of gas: our gas meter measures in cubic feet, which means we have to multiply by around… 31.5936106… to get the KWh… yes, really – more information here), but electricity is correspondingly 3.2 times more expensive per KWh – I have a separate chart to measure our daily energy costs, and it is if anything even more exciting (can you imagine!) than this one.

- Our gas usage grows dramatically in the winter – that’s what the big pink “lump” is. That’s sort-of what you’d expect on account of our gas central heating.

- Our electricity usage has trended downwards since the beginning of the year, when the solar panels were installed. It’s hard to see with the gas scale throwing it off (but again, the “cost per day” chart makes it very clear). There’s also a bit near the end where the electricity usage seems to fall of the bottom of the chart… more on that in a moment.

What got me sold on the idea of installing solar panels, though, was their long-term investment potential. I had the money sitting around anyway, and by my calculations we’ll get a significantly better return-on-investment out of our little roof-mounted power station than I would out of a high-interest savings account or bond. And that’s because of the oft-forgotten “third way” in which solar panelling pays for itself. Allow me to explain:

- Powering appliances: the first and most-obvious way in which solar power makes economic sense is that it powers your appliances. Right now, we generate almost as much electricity as we use (although because we use significantly more power in the evenings, only about a third of what which we generate goes directly into making our plethora of computers hum away).

- Selling back to the grid (export tariff): as you’re probably aware, it’s possible for a household solar array to feed power back into the National Grid: so the daylight that we’re collecting at times when we don’t need the electricity is being sold back to our energy company (who in turn is selling it, most-likely, to our neighbours). Because they’re of an inclination to make a profit, though (and more-importantly, because we can’t commit to making electricity for them when they need it: only during the day, and dependent upon sunlight), they only buy units from us at about a third of the rate that they sell them to consumers. As a result, it’s worth our while trying to use the power we generate (e.g. to charge batteries and to run things that can be run “at any point” during the day like the dishwasher, etc.) rather than to sell it only to have to buy it back.

- From a government subsidy (feed-in tariff): here’s the pleasant surprise – as part of government efforts to increase the proportion of the country’s energy that is produced from renewable sources, they subsidise renewable microgeneration. So if you install a wind turbine in your garden or a solar array on your roof, you’ll get a kickback for each unit of electricity that you generate. And that’s true whether you use it to power appliances or sell it back to the grid – in the latter case, you’re basically being paid twice for it! The rate that you get paid as a subsidy gets locked-in for ~20 years after you build your array, but it’s gradually decreasing. We’re getting paid a little over 14.5p per unit of electricity generated, per day.

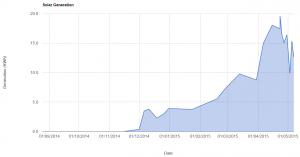

As the seasons have changed from Winter through Spring we’ve steadily seen our generation levels climbing. On a typical day, we now make more electricity than we use. We’re still having to buy power from the grid, of course, because we use more electricity in the evening than we’re able to generate when the sun is low in the sky: however, if (one day) technology like Tesla’s PowerWall becomes widely-available at reasonable prices, there’s no reason that a house like ours couldn’t be totally independent of the grid for 6-8 months of the year.

So: what are we saving/making? Well, looking at the last week of April and the first week of May, and comparing them to the same period last year:

- Powering appliances: we’re saving about 60p per day on electricity costs (down to about £1.30 per day).

- Selling back to the grid: we’re earning about 50p per day in exports.

- From a government subsidy: we’re earning about £2.37 per day in subsidies.

As I’m sure you can see: this isn’t peanuts. When you include the subsidy then it’s possible to consider our energy as being functionally “free”, even after you compensate for the shorter days of the winter. Of course, there’s a significant up-front cost in installing solar panels! It’s hard to say exactly when, at this point, I expect them to have paid for themselves (from which point I’ll be able to use the expected life of the equipment to more-accurately predict the total return-on-investment): I’m planning to monitor the situation for at least a year, to cover the variance of the seasons, but I will of course report back when I have more data.

I mentioned that the first graph wasn’t accurate? Yeah: so it turns out that our house’s original electricity meter was of an older design that would run backwards when electricity was being exported to the grid. Which was great to see, but not something that our electricity company approved of, on account of the fact that they were then paying us for the electricity we sold back to the grid, twice: for a couple of days of April sunshine, our electricity meter consistently ran backwards throughout the day. So they sent a couple of engineers out to replace it with a more-modern one, pictured above (which has a different problem: its “fraud light” comes on whenever we’re sending power back to the grid, but apparently that’s “to be expected”).

In any case, this quirk of our old meter has made some of my numbers from earlier this year more-optimistic than they might otherwise be, and while I’ve tried to compensate for this it’s hard to be certain that my estimates prior to its replacement are accurate. So it’s probably going to take me a little longer than I’d planned to have an accurate baseline of exactly how much money solar is making for us.

But making money, it certainly is.

Georgia (US) is trying to pass legislation that will let you pay for your solar panel installation from the savings you make from your decreased energy bill. I think this is a good way to get people to buy in. Flat costs now, reduced costs later.

I have no idea about what’s going on here in Japan.

That’s been an option in the UK for a few years now, but it’s not sufficiently widely-advertised for people to take notice. The loan still accrues interest (at around 6%), but it’s government-backed and there are rules that ensure that you can’t end up paying out more than you’re taking in/saving as a result of the panels. Most folks pay off the loan in about 15 years, which still leaves a theoretical 10 years of value out of the panels before their warranty runs out.

The UK government has a lot of schemes under the “Green Deal” brand that work in similar ways: e.g. they’ll pay for you to get a more-efficient boiler, cavity wall insulation, loft insulation, etc. and you pay them back out of the savings you make. It’s not bad.

The other major way that people get solar panels here on existing properties is through a “rent a roof” scheme, whereby you let a company install their panels on your roof: they take the subsidy, and you get the energy savings (as payment for the use of your roof). These have proven popular because there’s no initial outlay, but some homeowners have been stung by contractual clauses that say that e.g. if you have to take the panels down for a week to repair the roof, then you have to pay the company to compensate them for their losses in the meantime.

I had a pile of money lying around, so I bought ours outright from day one!

I wish it were feasible to get panels here in Virginia. Everything would be out of pocket though with no help. My whole house runs electric, no gas. It would be really nice.

Not even possible to get a loan/extend a mortgage to make it happen? You’re about 13° of latitude closer to the equator than I am, which means that you’ll get about an hour and a half more sun at the winter solstice (when you’ll want the electricity, if you’re using it for heating) and an hour and a half less sun at the summer solstice than me.

Even without the subsidies, it will pay for itself eventually. If you can calculate the return on investment and you can find a loan that accrues at less than that, it’s a no-brainer. Again, all depends on roof slope and angle, whether you plan to live there long enough to enjoy all of the benefits, creditworthiness etc., too. But certainly worth thinking about. For me, I paid outright for the panels because I realised that the savings/earnings I’m making on them are higher than the return-on-investment I’d get on the best-available savings accounts (plus I get to feel like I’m saving the planet!).