In 2023 I published an updated version of this blog post. See that post for the latest tips on managing polyfamily finances in a socialist manner.

For the last four years or so, Ruth, JTA and I (and during their times living with us, Paul and Matt) have organised our finances according to a system of means-assessment. I’ve mentioned it to people on a number of ocassions, and every time it seems to attract interest, so I thought I’d explain how we got to it and how it works, so that others might benefit from it. We think it’s particularly good for families consisting of multiple adults sharing a single household (for example, polyamorous networks like ours, or families with grown children) but there are probably others who’d benefit from it, too – it’s perfectly reasonable for just two adults with different salaries to use it, for example. And I’ve made a sample spreadsheet that you’re welcome to copy and adapt, if you’d like to.

How we got here

After I left Aberystwyth and Ruth, JTA, Paul and I started living at “Earth”, our house in Headington, we realised that for the first time, the four of us were financially-connected to one another. We started by dividing the rent and council tax four ways (with an exemption for Paul while he was still looking for work), splitting the major annual expenses (insurance, TV license) between the largest earners, and taking turns to pay smaller, more-regular expenses (shopping, bills, etc.). This didn’t work out very well, because it only takes two cycles of you being the “unlucky” one who gets lumbered with the more-expensive-than-usual shopping trip – right before a party, for example – before it starts to feel like a bit of a lottery.

Our solution, then, was to replace the system with a fairer one. We started adding up our total expenditures over the course of each month and settling the difference between one another at the end of each month. Because we’re clearly raging socialists, we decided that the fairest (and most “family-like”) way to distribute responsibility was by a system of partial means-assessment: de chacun selon ses facultés.

We started out with what we called “75% means-assessment”: in other words, a quarter of our shared expenditures were split evenly, four ways, and three-quarters were split proportionally in accordance with our gross income. We arrived at that figure after a little dissussion (and a computerised model that we could all play with on a big screen). Working from gross income invariably introduces inequalities into the system (some of which are mirrored in our income tax system) but a bigger unfairness came – as it does in wider society – from the fact that the difference between a very-low income and a low income is significantly more (from a disposable money perspective) than the difference between a low and a high income. This was relevant, because ‘personal’ expenses, such as mobile phone bills, were not included in the scheme and so we may have penalised lower-earners more than we had intended. On the other hand, 75% means-assessment was still significantly more-“communist” than 0%!

When I mentioned this system to people, sometimes they’d express surprise that I (as one of the higher earners) would agree to such an arrangement: the question was usually asked with a tone that implied that they expected the lower earners to mooch off of the higher earners, which (coupled with the clearly false idea that there’s a linear relationship between the amount of work involved in a job and the amount that it pays) would result in a “race to the bottom”, with each participant trying to do the smallest amount of work possible in order to maximise the degree to which they were subsidised by the others. From a game theory perspective, the argument makes sense, I would concede. But on the other hand – what the hell would I be doing agreeing to live with and share finances with (and then continuing to live with and share finances with) people whose ideology was so opposed to my own in the first place? Naturally, I trusted my fellow Earthlings in this arrangement: I already trusted them – that’s why I was living with them!

How it works

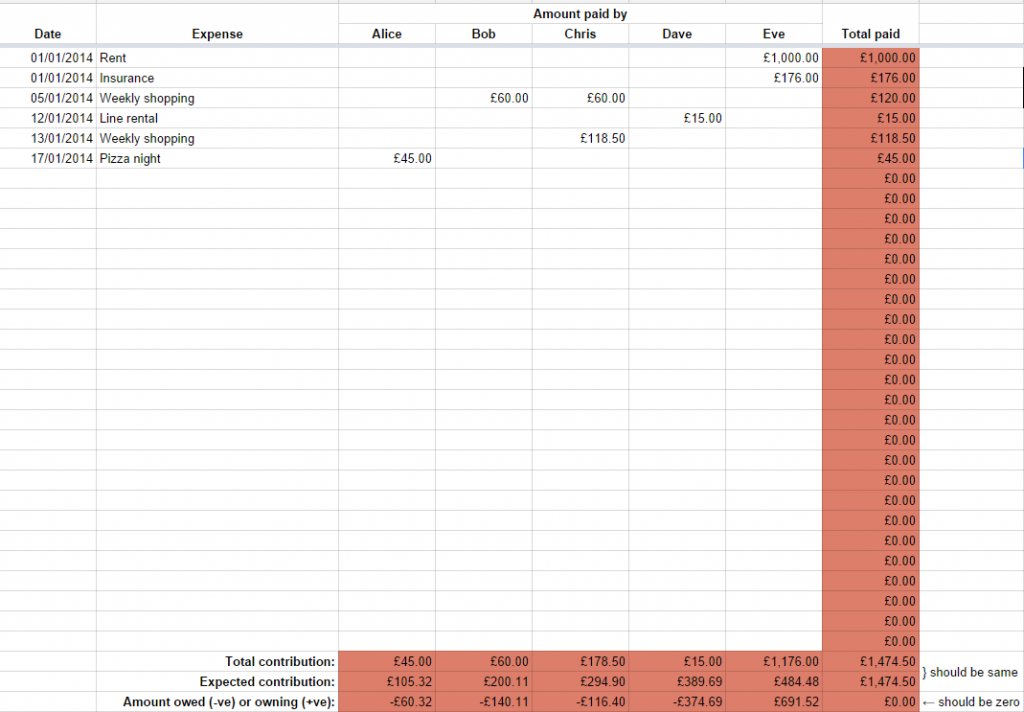

We’ve had a few iterations, but we eventually settled on a system at a higher rate of means-assessment: 100%! It’s not perfect, but it’s the fairest way I’ve ever been involved with of sharing the costs of running a house. I’ve put together a spreadsheet based on the one that we use that you can adapt to your own household, if you’d like to try a fairer way of splitting your bills – whether there are just two of you or lots of you in your home, this provides a genuinely equitable way to share your costs.

The sheet I’ve provided – linked above – is not quite like ours: ours has extra features to handle Ruth and I’s fluctuating income (mine because of freelance work, Ruth’s because she’s gradually returning to work following a period of maternity leave), an archive of each month’s finances, tools to help handle repayments to one another of money borrowed, and convenience macros to highlight who owes what to whom. This is, then, a simplified version from which you can build a model for your own household, or that you can use as a starting point for discussions with your own tribe.

Start on the “People” sheet and tell it how many participants your household has, their names, and their relative incomes. Also add your proposed level of means-assessment: anything from 0% to 100%… or beyond, but that does have some interesting philosophical consequences.

Then, on the “Expenses” sheet, record each thing that your household pays for over the course of each month. At the bottom, it’ll total up how much each person has paid, and how much they would have been expected to pay, based on the level of your means-assessment: at 0%, for example, each person would be expected to pay 1/N of the total; at the other extreme (100%), a person with no income would be expected to make no contribution, and a person with twice the income of another would be expected to pay twice as much as them. It’ll also show the difference between the two values: so those who’ve paid less than their ‘share’ will have negative numbers and will owe money to those who’ve paid more than their share, indicated by positive numbers. Settle the difference… and you’re ready to roll on to the next month.

Now you’re equipped to employ a (wholly or partially) means-assessed model to your household finances. If you adapt this model or have ideas for its future development, I’d love to hear them.

I am a huge fan of means-assessed expenses, who often shares commitments with those who are both uncomfortable with that, and yet don’t feel that splitting things equally is fair either (or who simply don’t want to live under a bridge in a cardboard box because one of N people is a grad student or starving artist).

So from that perspective, thanks for the % idea – the math isn’t much harder and it adds to the options if this comes up in future!

Indeed: it’s not perfect – at the very least, the inequalities inherent in the tax system get in the way, plus the fact that it’s based on total income, not disposable income which invariably makes it slightly biased in favour of the rich. Not to mention the fact that (taking a truly socialist perspective) different people might have different needs that aren’t covered within the household budget (e.g. for medication).

But it’s pretty good, and it can be expanded in interesting ways too: for example, two primary or monogamous couples sharing a household might opt to each use 100% means-assessment within each couple, but 50% means-assessment between the couples. The maths still isn’t very difficult (although my sample sheet won’t handle it without a little work) but it ‘works’.

Good luck!

This is amazing!

Semi-related question, how did getting a mortgage together work? My partners and I have been thinking about buying sometime in the next few years. Just unsure if 3 people can even sign for a mortgage. Did they take all your incomes into consideration?

Yes, a mortgage can be held by as many people as the lender will allow. I can’t speak for the world, of course, but here in the UK there’s certainly no legal restriction limiting the number of people that are co-signatories on a mortgage.

Our mortgage broker helped us find the best deal for us: he said that having three co-owners did reduce the number of available mortgages, but not by much. One side-effect of the whole thing, though, was that we had to fill out our application form on paper because the bank’s digital application forms weren’t built to accomodate more than 2 applicants on a form. [Boo! Mono privilege! etc.]

Having three incomes significantly improved the amount of money that we were able to borrow, of course, and while we naturally needed more money (in order to buy a bigger house!) we’re still making savings by having more people making use of our shared living spaces, etc.

Speak to a mortgage broker. If you’re in the UK, I’d be delighted to recommend ours, who was incredibly understanding: just drop me a PM.

Cool, thx!

We use a similar approach: we estimated first an amount of money we would use for ‘shared stuff’ like rent, food, daycare costs, insurance stuff etc. .

Then, each income first gets virtually reduced by ‘pocket money’ and by the costs for healthcare. Like this, even if someone does earn next to nothing, he/she is guaranteed to have some money left for ‘just spending’. Next, we sum up all income that is left and compute for each person how many percent of this (virtual) total income he/she earns.

The aforementioned amount of X$ is now divided according to these percentages, and everyone pays there share into a shared account where we all have access to.

If there is too much in the pot after a while, we do something nice; if we need more, we do ‘single payments’ to even things out.

What we like about it: it’s fair in terms of economic power (those who earn more pay more), and everyone has still their own money – plus access to ‘the pot’. This is, of course, a quite left wing view on things; your mileage may vary :)

Thx for sharing! I like the idea of splitting a part of the expenses not via percentages but in terms of ‘shares’, although I am not sure if, in the end, we would want to change our system.

We considered a system like that, but we soon discovered that we weren’t very good at the estimating part!

Everything that isn’t contributed to shared costs is ‘spending money’ for each individual, in our system: we still all have our “own money”. So for example: if our total mortgage repayments, bills, food shopping etc. for this month came to £2,000, of which I paid £1,200 from my salary of £1,500, and then at the end of the month the calculator says I should have paid only £800 (i.e. I “overpaid” by £400, and the others collectively “underpaid” by the same amount), then I’m owed £400 by the others. But regardless of anything else, the £600 I earned that wasn’t owed to the collective fund is ‘mine’ (and will probably be spent on, let’s face it, magic supplies, video games and booze).

This is a really cool method. I’ve never thought about using means assessment. We just combine all of our finances together and use them together and figure that people who contribute less financially are contributing in different ways.

Glad to hear this works for you. However, this kind of system seems intended for those just starting out and with very simple finances. It could also easily inspire resentment.

The reason I say “very simple finances” is that many people want to have income beyond just their job. People may also own assets, such as a house, that either provide income or shelter. How do you account for interest and dividend income, stock market gains (realized or unrealized), value of a house owned (which needs repairs and maintenance on an irregular basis), retirement or pension package contributions provided by one’s employer? Or just that one partner may have some savings and another does not?

And then of course there are expenses – the baby’s expenses being one obvious category that may or may not be shared by all partners. Also more mundane things, like one person spent more money than he/she could afford on a car, or another intentionally owns a very basic car, and the car(s) are shared by the household.

In short, I would find your system unworkable for all but the most simple households. But I do like that you bring up poly finances. In my mind, it works better when all partners who live together more or less have the same lifestyle. This often means one or more partners choosing to live well below their means, so as not to inspire jealousy or power issues with the others.

The partner who earns much less has issues as well. Such a partner would do well to save and develop their own nest egg. Kind of hard if others in the household are living a lifestyle way above one person’s means.

Finances can get quite complicated early on, even for a couple…heck even for a single. People’s values are reflected in how they earn/spend their money.

Interesting.

We have come across some of these issues already. We all own shares (in different companies), I own property outside of the one we live in which I rent out, two of us have significant savings, some of us are ocassionally eligible for bonuses, etc.

And so, in true poly style, we talk about it. Respectively: share income is small and it’s currently treated as negligible, although in practice it is used to treat us all, my rental income is averaged over a period, after costs, and treated as earned income, savings are ignored although it’s typically those with savings that make expensive up-front payments for mutual costs like holidays, house alterations, our new car etc. and then gradually reclaim from the rest (because we’d rather that the richest of us lose out on a little interest than that the poorest of us gain interest-bearing debt), bonuses are treated as negligible because for us, they are, but in practice they often go on treats that we all share.

And the baby? She’s a shared cost. Just because she’s not ‘mine’ doesn’t make her any less a part of my family.

That’s our answers to those questions, but they’re not everybody’s, I’m sure. You’re absolutely right to bring them up, and and family whose cashflow is affected by issues like these should, too! As I mentioned in my post, the spreadsheet I shared is a simplified version of ours (and that in turn is a simplified model of reality), abs it’s only meant to serve as a foundation for your own models. Just like polyamory itself, I’m not interested in telling you the ‘right’ way to do it: I just wanted to share one of the tools that helped us to find the right way for us!

Thanks again for your thoughts: I hope that others who are considering ways in which to blend their incomes fairly will see your valuable points and that it’ll help their discussion!

I’m curious how you do savings. From the comments it seems like most people keep their savings separate, but you could also use means-assessment for a shared savings account (for children, for instance). Of course, at some point you might as well just use joint bank accounts.

Right now, savings are separate (with the exception of a pot that’s being put aside for Annabel, currently funded from her Child Benefit but potentially from other sources too); however, we’ve started discussions about having a joint account or similar structure into which we all contribute, in our usual means-assessed proportions, to an agreed monthly target, as a “rainy day fund”.

I made a copy of this spreadsheet (I had been using my own version but it wasn’t as good), thank you so much for making it available to everyone :)