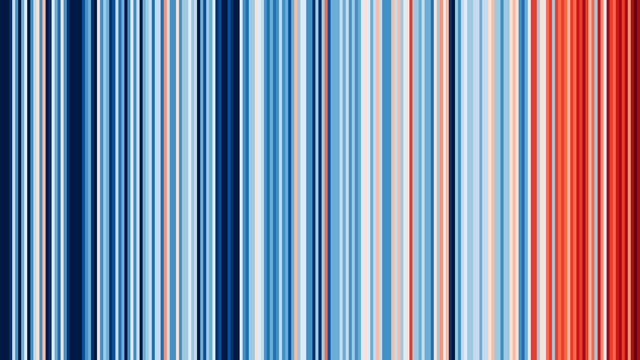

Not just a global issue but a local one too. A local one… almost everywhere.

Tag: environmentalism

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers

As soon as I finished reading its prequel, I started reading Becky Chambers’ A

Prayer for the Crown-Shy (and then, for various work/life reasons, only got around to publishing my micro-review just now).

As soon as I finished reading its prequel, I started reading Becky Chambers’ A

Prayer for the Crown-Shy (and then, for various work/life reasons, only got around to publishing my micro-review just now).

The book carries on directly from where A Psalm for the Wild-Built left off, to such a degree that at first I wondered whether the pair might have been better published as a single volume. But in hindsight, I appreciate the separation: there’s a thematic shift between the two that benefits from a little (literal) bookending.

Both Wild-Built and Crown-Shy look at the idea of individual purpose and identity, primarily through the vehicle of relatable protagonist Sibling Dex as they very-openly seek their place in the world, and to a lesser extent through the curiosity and inquisitiveness of the robot Mosscap.

But the biggest difference in my mind between the ways in which the two do so is the source of the locus of evaluation: the vast majority of Wild-Built is experienced only by Dex and Mosscap, alone together in the wilderness at the frontier between their disparate worlds. It maintains an internal locus of evaluation, with Dex asking questions of themselves about why they feel unfulfilled and Mosscap acting as a questioning foil and supportive friend. Crown-Shy, by contrast, pivots to a perceived external locus of evaluation: Dex and Mosscap return from the wilderness to civilisation, and both need to adapt to the experience of celebrity, questioning, and – in Mosscap’s case – a world completely-unfamiliar to it.

By looking more-carefully at Dex’s society, the book helps to remind us about the diverse nature of humankind. For example: we’re shown that even in a utopia, individual people will disagree on issues and have different philosophical outlooks… but the underlying message is that we can still be respectful and kind to one another, despite our disagreement. In the fourth chapter, the duo visit a coastland settlement whose residents choose to live a life, for the most part, without the convenience of electricity. By way of deference to their traditions, Dex (with their electric bike) and Mosscap (being an electronic entity) wait outside the village until invited in by one of the residents, and the trio enjoy a considerate discussion about the different value systems of people around the continent while casting fishing lines off a jetty. There’s no blame; no coercion; and while it’s implied that other residents of the village are staying well clear of the visitors, nothing more than this exclusion and being-separate is apparent. There’s sort-of a mutual assumption that people will agree-to-disagree and get along within the scope of their shared vision.

Which leads to the nub of the matter: while it appears that we’re seeing how Dex is viewed by others – by those they disagree with, by those who hold them with some kind of celebrity status, by their family with whom they – like many folks do – share a loving but not uncomplicated relationship – we’re actually still experiencing this internally. The questions on Dex’s mind remain “who am I?”, “what is my purpose?”, and “what do I want?”… questions only they can answer… but now they’re considering them from the context of their relationship with everybody else in their world, instead of their relationship with themself.

Everything I just wrote reads as very-pretentious, for which I apologise. The book’s much better-written than my review! Let me share a favourite passage, from a part of the book where Dex is introducing Mosscap to ‘pebs’, a sort-of currency used by their people, by way of explanation as to why people whom Mosscap had helped had given it pieces of paper with numbers written on (Mosscap not yet owning a computer capable of tracking its balance). I particularly love Mosscap’s excitement at the possibility that it might own things, an experience it previous had no need for:

…

Mosscap smoothed the crease in the paper, as though it were touching something rare and precious. “I know I’m going to get a computer, but can I keep this as well?”

“Yeah,” Dex said with a smile. “Of course you can.”

“A map, a note, and a pocket computer,” Mosscap said reverently. “That’s three belongings.” It laughed. “I’ll need my own wagon, at this rate.”

“Okay, please don’t get that much stuff,” Dex said. “But we can get you a satchel or something, if you want, so you don’t have things rattling around inside you.”

Mosscap stopped laughing, and looked at Dex with the utmost seriousness. “Could I really?” it said quietly. “Could I have a satchel?”

…

That’s just a heartwarming and childlike response to being told that you’re allowed to own property of your very own. And that’s the kind of comforting joy that, like its prequel, the entire book exudes.

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy is not quite so wondrous as A Psalm for the Wild-Built. How could it be, when we’re no longer quite so-surprised by the enthralling world in which it’s set. But it’s still absolutely magnificent, and I can wholeheartedly recommend the pair.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

I’d already read every prior book published by the excellent Becky Chambers, but this (and its sequel) had been sitting on my to-read list for some time,

and so while I’ve been ill and off work these last few days, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to

pick it up. I’ve spent most of this week so far in bed, often drifting in and out of sleep, and a lightweight novella that I coud dip in and out of over the course of a day felt like

the ideal comfort.

I’d already read every prior book published by the excellent Becky Chambers, but this (and its sequel) had been sitting on my to-read list for some time,

and so while I’ve been ill and off work these last few days, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to

pick it up. I’ve spent most of this week so far in bed, often drifting in and out of sleep, and a lightweight novella that I coud dip in and out of over the course of a day felt like

the ideal comfort.

I couldn’t have been more right, as the very first page gave away. My friend Ash described the experience of reading it (and its sequel) as being “like sitting in a warm bath”, and I see where they’re coming from. True to form, Chambers does a magnificent job of spinning a believable utopia: a world that acts like an idealised future while still being familiar enough for the reader to easily engage with it. The world of Wild-Built is inhabited by humans whose past saw them come together to prevent catastrophic climate change and peacefully move beyond their creation of general-purpose AI, eventually building for themselves a post-scarcity economy based on caring communities living in harmony with their ecosystem.

Writing a story in a utopia has sometimes been seen as challenging, because without anything to strive for, what is there for a protagonist to strive against? But Wild-Built has no such problem. Written throughout with a close personal focus on Sibling Dex, a city monk who decides to uproot their life to travel around the various agrarian lands of their world, a growing philosophical theme emerges: once ones needs have been met, how does one identify with ones purpose? Deprived of the struggle to climb some Maslowian pyramid, how does a person freed of their immediate needs (unless they choose to take unnecessary risks: we hear of hikers who die exploring the uncultivated wilderness Dex’s people leave to nature, for example) define their place in the world?

Aside from Dex, the other major character in the book is Mosscap, a robot whom they meet by a chance encounter on the very edge of human civilisation. Nobody has seen a robot for centuries, since such machines became self-aware and, rather than consign them to slavery, the humans set them free (at which point they vanished to go do their own thing).

To take a diversion from the plot, can I just share for a moment a few lines from an early conversation between Dex and Mosscap, in which I think the level of mutual interpersonal respect shown by the characters mirrors the utopia of the author’s construction:

…

“What—what are you? What is this? Why are you here?”

The robot, again, looked confused. “Do you not know? Do you no longer speak of us?”

“We—I mean, we tell stories about—is robots the right word? Do you call yourself robots or something else?”

“Robot is correct.”

…

“Okay. Mosscap. I’m Dex. Do you have a gender?”

“No.”

“Me neither.”

These two strangers take the time in their initial introduction to ensure they’re using the right terms for one another: starting with those relating to their… let’s say species… and then working towards pronouns (Dex uses they/them, which seems to be widespread and commonplace but far from universal in their society; Mosscap uses it/its, which provides for an entire discussion on the nature of objectship and objectification in self-identity). It’s queer as anything, and a delightful touch.

In any case: the outward presence of the plot revolves around a question that the robot has been charged to find an answer to: “What do humans need?” The narrative theme of self-defined purpose and desires is both a presenting and a subtextual issue, and it carries through every chapter. The entire book is as much a thought experiment as it is a novel, but it doesn’t diminish in the slightest from the delightful adventure that carries it.

Dex and Mosscap go on to explore the world, to learn more about it and about one another, and crucially about themselves and their place in it. It’s charming and wonderful and uplifting and, I suppose, like a warm bath: comfortable and calming and centering. And it does an excellent job of setting the stage for the second book in the series, which we’ll get to presently…

Any Cup

Water Science #2

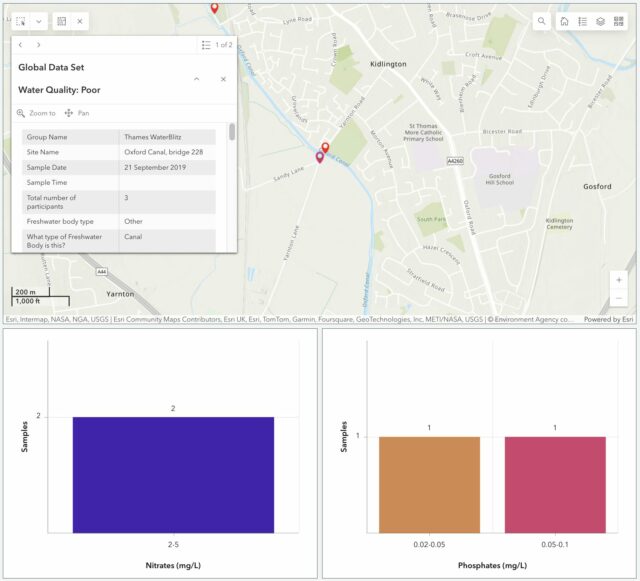

Back in 2019, the kids – so much younger back then! – and I helped undertake some crowdsourced citizen science for the Thames WaterBlitz. This year, we’re helping out again.

We’ve moved house since then, but we’re still within the Thames basin and can provide value by taking part in this weekend’s sampling activity. The data that gets collected on nitrate and phosphate levels in local water sources – among other observations – gets fed into an open dataset for the benefit of scientists and laypeople.

It’d have been tempting to be exceptionally lazy and measure the intermittent water course that runs through our garden! It’s an old, partially-culverted drainage ditch1, but it’s already reached the “dry” part of its year and taking a sample wouldn’t be possible right now.

But more-importantly: the focus of this season’s study is the River Evenlode, and we’re not in its drainage basin! So we packed up a picnic and took an outing to the North Leigh Roman Villa, which I first visited last year when I was supposed to be on the Isle of Man with Ruth.

Our lunch consumed, we set off for the riverbank, and discovered that the field between us and the river was more than a little waterlogged. One of the two children had been savvy enough to put her wellies on when we suggested, but the other (who claims his wellies have holes in, or don’t fit, or some other moderately-implausible excuse for not wearing them) was in trainers and Ruth and I needed to do a careful balancing act, holding his hands, to get him across some of the tougher and boggier bits.

Eventually we reached the river, near where the Cotswold Line crosses it for the fifth time on its way out of Oxford. There, almost-underneath the viaduct, we sent the wellie-wearing eldest child into the river to draw us out a sample of water for testing.

Looking into our bucket, we were pleased to discover that it was, relatively-speaking, teeming with life: small insects and a little fish-like thing wriggled around in our water sample2. This, along with the moorhen we disturbed3 as we tramped into the reeds, suggested that the river is at least in some level of good-health at this point in its course.

We were interested to observe that while the phosphate levels in the river were very high, the nitrate levels are much lower than they were recorded near this spot in a previous year. Previous years’ studies of the Evenlode have mostly taken place later in the year – around July – so we wondered if phosphate-containing agricultural runoff is a bigger problem later in the Spring. Hopefully our data will help researchers answer exactly that kind of question.

Regardless of the value of the data we collected, it was a delightful excuse for a walk, a picnic, and to learn a little about the health of a local river. On the way back to the car, I showed the kids how to identify wild garlic, which is fully in bloom in the woods nearby, and they spent the rest of the journey back chomping down on wild garlic leaves.

The car now smells of wild garlic. So I guess we get a smelly souvenir from this trip, too4!

Footnotes

1 Our garden ditch, long with a network of similar channels around our village, feeds into Limb Brook. After a meandering journey around the farms to the East this eventually merges with Chill Brook to become Wharf Stream. Wharf Stream passes through a delightful nature reserve before feeding into the Thames near Swinford Toll Bridge.

2 Needless to say, we were careful not to include these little animals in our chemical experiments but let them wait in the bucket for a few minutes and then be returned to their homes.

3 We didn’t catch the moorhen in a bucket, though, just to be clear.

4 Not counting the smelly souvenir that was our muddy boots after splodging our way through a waterlogged field, twice

[Bloganuary] Live Long and Prosper

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What are your thoughts on the concept of living a very long life?

Today’s my 43rd birthday. Based on the current best statistics available for my age and country, I might expect to live about the same amount of time again: I’m literally about half-way through my anticipated life, today.1

Naturally, that’s the kind of shocking revelation that can make a person wish for an extended lifespan. Especially if, y’know, you read Andrew’s book on the subject and figured that, excitingly, we’re on the cusp of some meaningful life extension technologies!

My very first thought when I read Andrew’s thoughts on lifespan extension was exactly the kind of knee-jerk panic response he tries to assuage with his free bonus chapter. He spends a while explaining how he’s not just talking about expending lifespan but healthspan, and so the need healthcare resources that are used to treat those in old-age wouldn’t increase dramatically as a result of lifespan increase, but that’s not the bit that worries me. My concern is that lifespan extension technologies will be unevenly distributed, and the (richer) societies that get them first are those same societies whose (richer) lifestyle has the greater negative impact on the Earth’s capacity to support human life.2

Andrew anticipates this concern and does some back-of-napkin maths to suggest that the increase in population doesn’t make too big an impact:

In this ‘worst’ case, the population in 2050 would be 11.3 billion—16% larger than had we not defeated ageing.

Is that a lot? I don’t think so—I’d happily work 16% harder to solve environmental problems if it meant no more suffering from old age.

This seems to me to be overly-optimistic:

- The Earth doesn’t care whether or not you’re happy to work 16% harder to solve environmental problems if that extra effort isn’t possible (there’s necessarily an upper limit to how much change we can actually effect).

- 16% extra population = 16% extra “work” to save them implies a linear relationship between the two that simply doesn’t exist.

- And that you’re willing to give 16% more doesn’t matter a jot if most of the richest people on the planet don’t share that ideal.

Fortunately, I’m reassured by the fact that – as Andrew points out – change is unlikely to happen fast. That means that the existing existential threat of climate change remains a bigger and more-significant issue than potential future overpopulation does!

In short: while I’m hoping I’ll live happily and healthily to say 120, I don’t think I’m ready for the rest of the world to all suddenly start doing so too! But I think there are bigger worries in the meantime. I don’t fancy my chances of living long enough to find out.

Gosh, that’s a gloomy note for a birthday, isn’t it? I’d better get up and go do something cheerier to mark the day!

Footnotes

1 Assuming I don’t die of something before them, of course. Falling off a cliff isn’t a heritable condition, is it? ‘Cos there’s a family history of it, and I’ve always found myself affected by the influence of gravity, which I believe might be a precursor to falling off things.

2 Fun fact: just last month I threw together a little JavaScript simulator to illustrate how even with no population growth (a “replacement rate” of one child per adult) a population grows while its life expectancy grows, which some people find unintuitive.

[Bloganuary] A Different Diet

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What could you do differently?

Well that sounds like a question lifted right off an Oblique Strategies deck if ever I heard one!

I occasionally aspire to something-closer-to-veganism. Given that my vegetarianism (which is nowadays a compromise position1 of “no meat on weekdays, no beef or lamb at all”) comes primarily from a place of environmental concern: a Western meat-eating diet is vastly less-efficient in terms of energy conversion, water usage, and carbon footprint than a vegetarian or vegan diet.

From an environmental perspective, the biggest impact resulting from my diet is almost certainly: dairy products. I’m not even the hugest fan of cheese, but I seem to eat plenty of it, and it’s one of those things that they just don’t seem to be able to make plant-based alternatives to perfectly, yet.

In an ideal world, with more willpower, I’d be mostly-vegan. I’d eat free range eggs produced by my own chickens, because keeping your own chickens offsets the food miles by enough to make them highly-sustainable. I’d eat honey, because honestly anything we can do to encourage more commercial beekeeping is a good thing as human civilisation depends on pollinators. But I’d drop all dairy from my diet.

I suppose I’m not that far off, yet. Maybe this year I can try switching-in a little more vegan “cheese” into the rotation.

Footnotes

1 I missed many meats. But also, I don’t like to be an inconvenience.

Will swapping out electric car batteries catch on?

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I won’t be plugging it in though, instead, the battery will be swapped for a fresh one, at this facility in Norway belonging to Chinese electric carmaker, Nio.

The technology is already widespread in China, but the new Power Swap Station, just south of Oslo, is Europe’s first.

…

This is what I’ve been saying for years would be a better strategy for electric vehicles. Instead of charging them (the time needed to charge is their single biggest weakness compared to fuelled vehicles) we should be doing battery swaps. A decade or two ago I spoke hopefully for some kind of standardised connector and removal interface, probably below the vehicle, through which battery cells could be swapped-out by robots operating in a pit. Recovered batteries could be recharged and reconditioned by the robots at their own pace. People could still charge their cars in a plug-in manner at their homes or elsewhere.

You’d pay for the difference in charge between the old and replacement battery, plus a service charge for being part of the battery-swap network, and you’d be set. Car manufacturers could standardise on battery designs, much like the shipping industry long-ago standardised on container dimensions and whatnot, to take advantage of compatibility with the wider network.

Rather than having different sizes of battery, vehicles could be differentiated by the number of serial battery units installed. A lorry might need four or five units; a large car two; a small car one, etc. If the interface is standardised then all the robots need to be able to do is install and remove them, however many there are.

This is far from an unprecedented concept: the centuries-old idea of stagecoaches (and, later, mail coaches) used the same idea, but with the horses being changed at coaching inns rather. Did you know that the “stage” in stagecoach refers to the fact that their journey would be broken into stages by these quick stops?

Anyway: I dismayed a little when I saw every EV manufacturer come up with their own battery standards, co=operating only as far as the plug-in charging interfaces (and then, only gradually and not completely!). But I’m given fresh hope by this discovery that China’s trying to make it work, and Nio‘s movement in Norway is exciting too. Maybe we’ll get there someday.

Incidentally: here’s a great video about how AC charging works (with a US/type-1 centric focus), which briefly touches upon why battery swaps aren’t necessarily an easy problem to solve.

Say… “Cheese?”

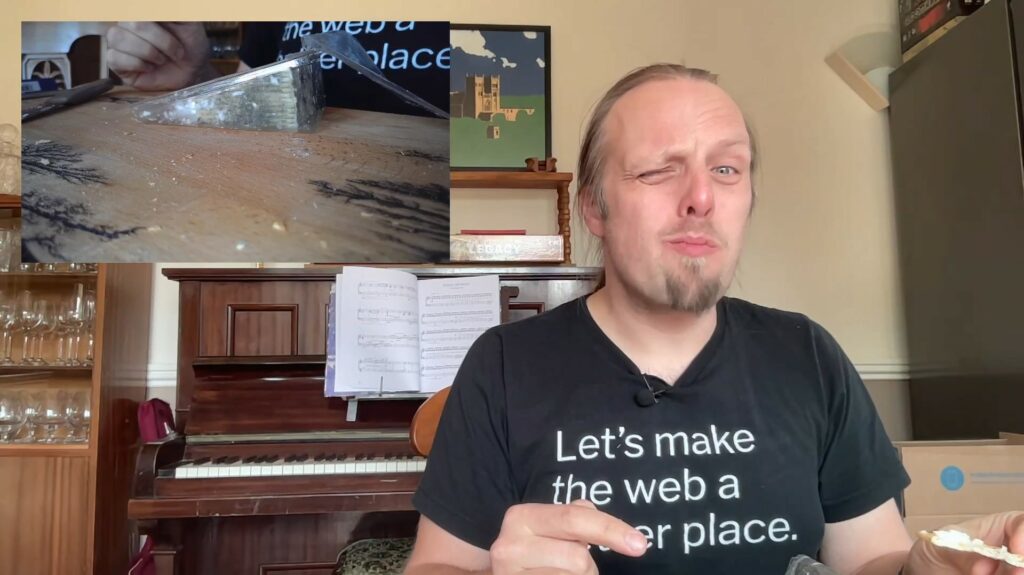

For lunch today I taste-tested five different plant-based vegan “cheeses” from Honestly Tasty. Let’s see if they’re any good.

Prefer video?

This blog post is available as a video (here or on YouTube), for those who like that sort of thing. The content’s slightly different, but you do get to see my face when I eat the one that doesn’t agree with me.

Background

I’ve been vegetarian or mostly-vegetarian to some degree or another for a little over ten years (for those who have trouble keeping up: I currently eat meat only on weekends, and not including beef or lamb), principally for the environmental benefits of a reduced-meat lifestyle. But if I’m really committed to reducing the environmental impact of my diet, the next “big” thing I still consume is dairy products.

My milk consumption is very low nowadays, but – like many people who might aspire towards dropping dairy – it’s quitting cheese that poses the biggest challenge. I’m not even the biggest fan of cheese, and I don’t know how I’d do without it: there’s just, it seems, no satisfactory substitute.

It’s possible, though, that my thinking on this is outdated. Especially in recent years, we’re getting better and better at making convincing (or, at least, tasty!) plant-based substitutes to animal based foods. And so, inspired by a conversation with some friends, I thought I’d try a handful of new-generation plant-based cheeses and see how I got on. I ordered a variety pack from Honestly Tasty (who’ll give you 20% off your first order if you subscribe your favourite throwaway email address to their newsletter) and gave it a go.

Bree

It’s supposed to taste like Brie, I guess, but it’s not convincing. The texture of the rind is surprisingly good, but the inside is somewhat homogeneous and flat. They’ve tried to use

mustard powder to provide Brie’s pepperiness and acetic acid for its subtle sourness, but it feels like there might be too much of the former (or perhaps I’m just a little oversensitive

to mustard) and too little of the latter. It’s okay, but I wouldn’t buy it again.

Ched Spread

This was surprisingly flavoursome and really quite enjoyable. It spreads with about the consistency of pâté and has a sharp tang that really stands out. You wouldn’t mistake it for

cheese, but you might mistake it for a cheese spread: there’s a real “cheddary” flavour buried in there.

Blue

This is supposed to be modelled after Gorgonzola, and it might as well be because I don’t like either it or the cheese it’s based on. I might loathe Blue slightly less than

most blue cheeses, but that doesn’t mean I’d willingly subject myself to this again in a hurry. It’s matured with real Penicillium Roqueforti, apparently, along with seaweed, and it

tastes like both of these things are true. So yeah: I hated this one, but you shouldn’t take that as a condemnation of its quality as a cheese substitute because I’d still rather eat it

than the cheese that it’s based on. Try for yourself, I guess.

Herbi

This was probably my favourite of the bunch. It’s reminiscent of garlic & herb Boursin, and feels like somebody in the

kitchen where they cooked it up said to themselves, “how about we do the Ched Spread, but with less onion and a whole load of herbs mixed-through”. It seems that it must be easier to

make convincingly-cheesy soft cheeses than hard cheeses, but I’m not complaining: this would be great on toast.

Shamembert

If you’d served me this and told me it was a baked Camembert… I wouldn’t be fooled. But I wouldn’t be disappointed either. It moves a lot like Camembert and it tastes… somewhat like it.

But whether or not that’s “enough” for you, it’s perfectly delicious and I’d be more than happy to eat it or serve it to others.

In summary…

Honestly Tasty’s Ched Spread, Herbi, and Shamembert are perfectly acceptable (vegan!) substitutes for cheese. Even where they don’t accurately reflect the cheese they attempt to model, they’re still pretty good if you take them on their own merits: instead of comparing them to their counterparts, consider each as if it were a cheese spread or soft cheese in its own right and enjoy accordingly. I’d buy them again.

Their Bree failed to capture the essence of a good ripe Brie and its flavour profile wasn’t for me something to enjoy outside of its attempts at emulation. And their “Veganzola” Blue cheese… was pretty grim, but then that’s what I think of Gorgonzola too, so maybe it’s perfect and I just haven’t the palate for it.

Coca-Cola company trials first paper bottle

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Coca-Cola is to test a paper bottle as part of a longer-term bid to eliminate plastic from its packaging entirely.

The prototype is made by a Danish company from an extra-strong paper shell that still contains a thin plastic liner.

But the goal is to create a 100% recyclable, plastic-free bottle capable of preventing gas escaping from carbonated drinks.

The barrier must also ensure no fibres flake off into the liquid.

…

If only somebody could invent a bottle suitable for containing Coca-Cola but 100% recyclable, plastic-free, and food safe.

Oh wait… for the vast majority of its history, all Coca-Cola bottles have met this description! The original Coke bottles, back in 1899, were made of glass with a metal top. Glass is infinitely-recyclable (it’s also suitable for pressure-washing and reusing, saving even more energy, as those who receive doorstep milk deliveries already know) and we already have a recycling infrastructure for it in place. Even where new glass needs to be made from scratch, its raw ingredient is silica, one of the most abundant natural resources on the planet!

Bottle caps can be made of steel or aluminium and can be made in screw-off varieties in case you don’t have a bottle opener handy. Both steel and aluminium are highly-recyclable, and again with infrastructure already widespread. Many modern “metal” caps contain a plastic liner to ensure a good airtight fit (especially if it’s a screw cap, which are otherwise less-tight), but there are environmentally-friendly alternatives: bioplastics or cork, for example.

The worst things about glass are its fragility – which is a small price to pay – and its weight (making distribution more expensive and potentially more-polluting). But that latter can easily be overcome by distributing bottling: a network of bottling plants around the country (each bottling a variety of products, and probably locally-connected to reclamation and recycling schemes) would allow fluids to be transported in bulk – potentially even in concentrate form, further improving transport efficiency… and that’s if it isn’t just more ecologically-sound to produce Coke more-locally rather than transporting it over vast distances: it’s not like the recipe is particularly complicated.

In short: this is the stupidest environmental initiative I’ve seen yet this year.

Digital Climate Strike’s Carbon Footprint

Ironically, the web page promoting the “Digital Climate Strike” is among the dirtiest on the Internet, based on the CO2 footprint of visiting it.

Going to that page results in about 14 Mb of data being transmitted from their server to your device (which you’ll pay for if you’re on a metered connection). For comparison, reading my recent post about pronouns results in about 356 Kb of data. In other words, their page is forty times more bandwidth-consuming, despite the fact that my page has about four times the word count. The page you’re reading right now, thanks to its images, weighs in at about 650 Kb: you could still download it more than twenty times while you were waiting for theirs.

Worse still, the most-heavyweight of the content they deliver is stuff that’s arguably strictly optional and doesn’t add to the message:

- Eight different font files are served from three different domains (the fonts alone consume about 140 Kb) – seven more are queued but not used.

- Among the biggest JavaScript files they serve is that of Hotjar analytics: I understand the importance of measuring your impact, but making your visitors – and the planet – pay for it is a little ironic.

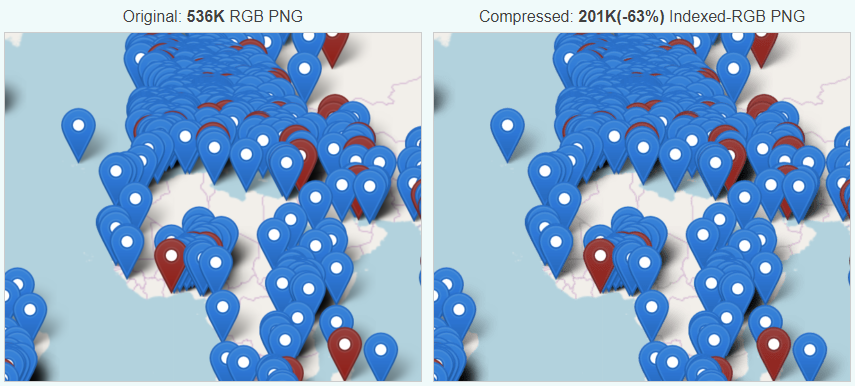

- The biggest JavaScript file seems to be for Mapbox, which as far as I can see is never actually used: that map on the page is a static image which, incidentally, I was able to reduce from 0.5 Mb to 0.2 Mb just by running it through a free online image compressor.

And because the site sets virtually no caching headers, even if you’ve visited the website before you’re likely to have to download the whole thing again. Every single time.

It’s not just about bandwidth: all of those fonts, that JavaScript, their 60 Kb of CSS (this page sent you 13 Kb) all has to be parsed and interpreted by your device. If you’re on a mobile device or a laptop, that means you’re burning through lithium (a non-renewable resource whose extraction and disposal is highly polluting) and

regardless of your device you’re using you’re using more electricity to visit their site than you need to. Coding antipatterns like document.write() and active event

listeners that execute every time you scroll the page keep your processor working hard, turning electricity into waste heat. It took me over 12 seconds on a high-end smartphone and a

good 4G connection to load this page to the point of usability. That’s 12 seconds of a bright screen, a processor running full tilt,a data connection working its hardest, and a

battery ticking away. And I assume I’m not the only person visiting the website today.

This isn’t really about this particular website, of course (and I certainly don’t want to discourage anybody from the important cause of saving the planet!). It’s about the bigger picture: there’s a widespread and long-standing trend in web development towards bigger, heavier, more power-hungry websites, built on top of heavyweight frameworks that push the hard work onto the user’s device and which favour developer happiness over user experience. This is pretty terrible: it makes the Web slow, and brittle, and it increases the digital divide as people on slower connections and older devices get left behind.

(Bonus reading: luckily there’s a counterculture of lean web developers…)

But this trend is also bad for the environment, and when your website exists to try to save it, that’s more than a little bit sad.

Watch UK’s Natural Land Diminish in 100 Seconds

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

If the different land uses of the UK were divided up into their percentage-ratio blocks, what would a 100-second tour of the country (with each second covering a single percent of the land usage) look like?

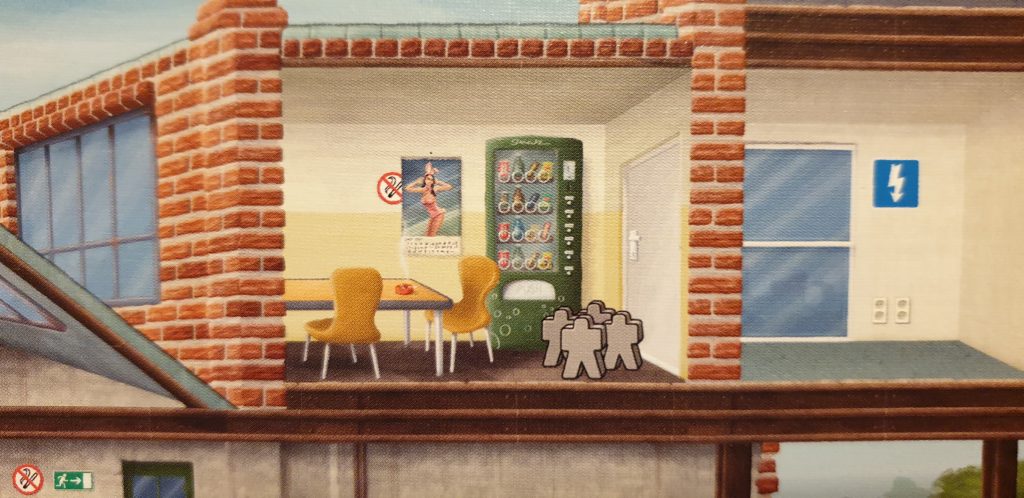

What can board game strategy tell us about the future of the car wash?

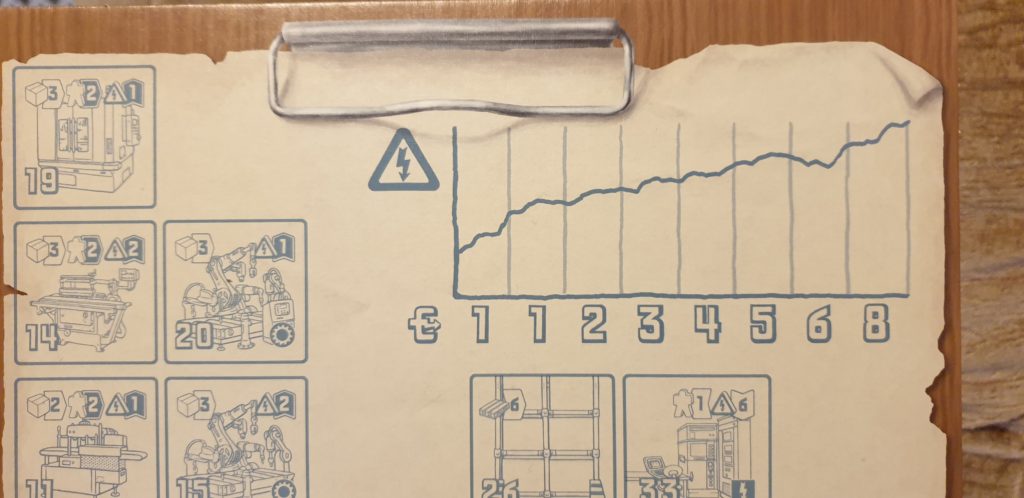

I’m increasingly convinced that Friedemann Friese‘s 2009 board game Power Grid: Factory Manager (BoardGameGeek) presents gamers with a highly-digestible model of the energy economy in a capitalist society. In Factory Manager, players aim to financially-optimise a factory over time, growing production and delivery capacity through upgrades in workflow, space, energy, and staff efficiency. An essential driving factor in the game is that energy costs will rise sharply throughout. Although it’s not always clear in advance when or by how much, this increase in the cost of energy is always at the forefront of the savvy player’s mind as it’s one of the biggest factors that will ultimately impact their profit.

Given that players aim to optimise for turnover towards the end of the game (and as a secondary goal, for the tie-breaker: at a specific point five rounds after the game begins) and not for business sustainability, the game perhaps-accidentally reasonably-well represents the idea of “flipping” a business for a profit. Like many business-themed games, it favours capitalism… which makes sense – money is an obvious and quantifiable way to keep score in a board game! – but it still bears repeating.

There’s one further mechanic in Factory Manager that needs to be understood: a player’s ability to control the order in which they take their turn and their capacity to participate in the equipment auctions that take place at the start of each round is determined by their manpower-efficiency in the previous round. That is: a player who operates a highly-automated factory running on a skeleton staff benefits from being in the strongest position for determining turn order and auctions in their next turn.

The combination of these rules leads to an interesting twist: in the final turn – when energy costs are at their highest and there’s no benefit to holding-back staff to monopolise the auction phase in the nonexistent subsequent turn – it often makes most sense strategically to play what I call the “sweatshop strategy”. The player switches off the automated production lines to save on the electricity bill, drags in all the seasonal workers they can muster, dusts off the old manpower-inefficient machines mouldering in the basement, and gets their army of workers cranking out widgets!

With indefinitely-increasing energy prices and functionally-flat staff costs, the rules of the game would always eventually reach the point at which it is most cost-effective

to switch to slave cheap labour rather than robots. but Factory Manager‘s fixed-duration means that this point often comes for all players in many games at the same

predictable point: a tipping point at which the free market backslides from automation to human labour to keep itself alive.

There are parallels in the real world. Earlier this month, Tim Watkins wrote:

The demise of the automated car wash may seem trivial next to these former triumphs of homo technologicus but it sits on the same continuum. It is just one of a gathering list of technologies that we used to be able to use, but can no longer express (through market or state spending) a purpose for. More worrying, however, is the direction in which we are willingly going in our collective decision to move from complexity to simplicity. The demise of the automated car wash has not followed a return to the practice of people washing their own cars (or paying the neighbours’ kid to do it). Instead we have more or less happily accepted serfdom (the use of debt and blackmail to force people to work) and slavery (the use of physical harm) as a reasonable means of keeping the cost of cleaning cars to a minimum (similar practices are also keeping the cost of food down in the UK). This, too, is precisely what is expected when the surplus energy available to us declines.

I love Factory Manager, but after reading Watkins’ article, it’ll probably feel a little different to play it, now. It’s like that moment when, while reading the rules, I first poured out the pieces of Puerto Rico. Looking through them, I thought for a moment about what the “colonist” pieces – little brown wooden circles brought to players’ plantations on ships in a volume commensurate with the commercial demand for manpower – represented. And that realisation adds an extra message to the game.

Beneath its (fabulous) gameplay, Factory Manager carries a deeper meaning encouraging the possibility of a discussion about capitalism, environmentalism, energy, and sustainability. And as our society falters in its ability to fulfil the techno-utopian dream, that’s perhaps a discussion we need to be having.

But for now, go watch Sorry to Bother You, where you’ll find further parallels… and at least you’ll get to laugh as you do so.

Alpha-Gal and the Gaia Hypothesis

Ticking Point

An increasing number of people are reportedly suffering from an allergy to the meat and other products of nonhuman mammals, reports Mosaic Science this week, and we’re increasingly confident that the cause is a sensitivity to alpha-gal (Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose), a carbohydrate produced in the bodies of virtually all mammals except for us and our cousin apes, monkeys, and simians (and one of the reasons you can’t transplant tissue from pigs to humans, for example).

The interesting thing is that the most-common cause of alpha-gal sensitivity appears to be the bite of one of a small number of species of tick. The most-likely hypothesis seems to be that being bitten by such a tick after it’s bitten e.g. deer or cattle may introduce that species’ alpha-gal directly to your bloodstream. This exposure triggers an immune response through all future exposure, even if it’s is more minor, e.g. consuming milk products or even skin contact with an animal.

That’s nuts, isn’t it? The Mosaic Science article describes the reaction of Tami McGraw, whose symptoms began in 2010:

[She] asked her doctor to order a little-known blood test that would show if her immune system was reacting to a component of mammal meat. The test result was so strongly positive, her doctor called her at home to tell her to step away from the stove.

That should have been the end of her problems. Instead it launched her on an odyssey of discovering just how much mammal material is present in everyday life. One time, she took capsules of liquid painkiller and woke up in the middle of the night, itching and covered in hives provoked by the drug’s gelatine covering.

When she bought an unfamiliar lip balm, the lanolin in it made her mouth peel and blister. She planned to spend an afternoon gardening, spreading fertiliser and planting flowers, but passed out on the grass and had to be revived with an EpiPen. She had reacted to manure and bone meal that were enrichments in bagged compost she had bought.

Of course, this isn’t the only nor even the most-unusual (or most-severe) animal-induced allergy-to-a-different-animal we’re aware of. The hilariously-named but terribly-dangerous Pork-Cat syndrome is caused, though we’re not sure how, by exposure to cats and results in a severe allergy to pork. But what makes alpha-gal sensitivity really interesting is that it’s increasing in frequency at quite a dramatic rate. The culprit? Climate change. Probably.

It’s impossible to talk to physicians encountering alpha-gal cases without hearing that something has changed to make the tick that transmits it more common – even though they don’t know what that something might be.

…

“Climate change is likely playing a role in the northward expansion,” Ostfeld adds, but acknowledges that we don’t know what else could also be contributing.

Meat Me Half-Way

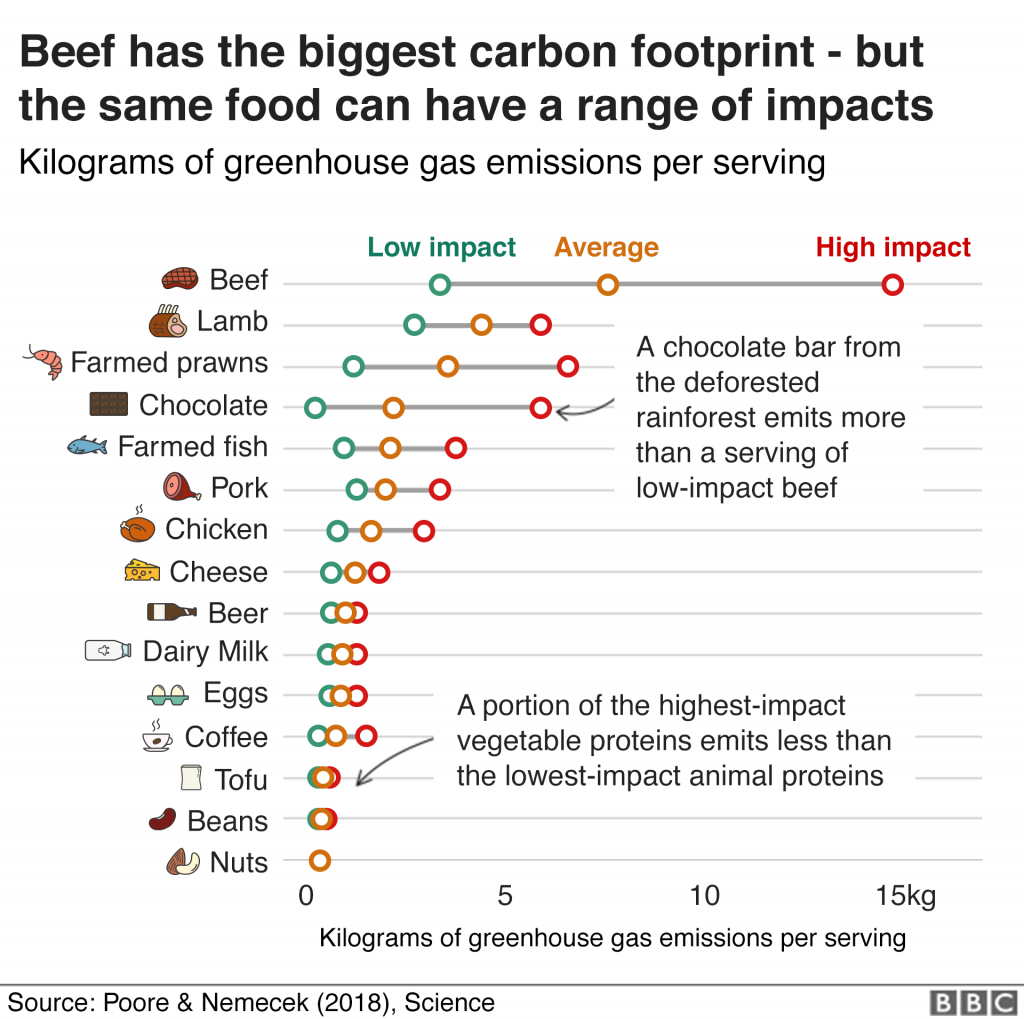

To take a minor diversion: another article I saw this week was the BBC‘s one on the climate footprint of the food you eat.

A little dated, perhaps: I’m sure that nobody needs to be told nowadays that one of the biggest things a Westerner can do to reduce their personal carbon footprint (after from breeding less or not at all, which I maintain is the biggest, or avoiding air travel, which Statto argues for) is to reduce or refrain from consumption of meat (especially pork and beef) and dairy products.

Indeed, environmental impact was the biggest factor in my vegetarianism (now weekday-vegetarianism) for the last eight years, and it’s an outlook that I’ve seen continue to grow in others over the same period.

Seeing these two stories side-by-side in my RSS reader put the Gaia hypothesis in my mind.

If you’re not familiar with the Gaia hypothesis, the basic idea is this: by some mechanism, the Earth and all of the life on it act in synergy to maintain homeostasis. Organisms not only co-evolve with one another but also with the planet itself, affecting their environment in a way that in turn affects their future evolution in a perpetual symbiotic relationship of life and its habitat.

Its advocates point to negative feedback loops in nature such as plankton blooms affecting the weather in ways that inhibit plankton blooms and to simplistic theoretical models like the Daisyworld Simulation (cute video). A minority of its proponents go a step further and describe the Earth’s changes teleologically, implying a conscious Earth with an intention to protect its ecosystems (yes, these hypotheses were born out of the late 1960s, why do you ask?). Regardless, the essence is the same: life’s effect on its environment affects the environment’s hospitality to life, and vice-versa.

There’s an attractive symmetry to it, isn’t there, in light of the growth in alpha-gal allergies? Like:

- Yesterday – agriculture, particularly intensive farming of mammals, causes climate change.

- Today – climate change causes ticks to spread more-widely and bite more humans.

- Tomorrow – tick bites cause humans to consume less products farmed from mammals?

That’s not to say that I buy it, mind. The Gaia hypothesis has a number of problems, and – almost as bad – it encourages a complacent “it’ll all be okay, the Earth will fix itself” mindset to climate change (which, even if it’s true, doesn’t bode well for the humans residing on it).

But it was a fun parallel to land in my news reader this morning, so I thought I’d share it with you. And, by proxy, make you just a little bit warier of ticks than you might have been already. /shudders/

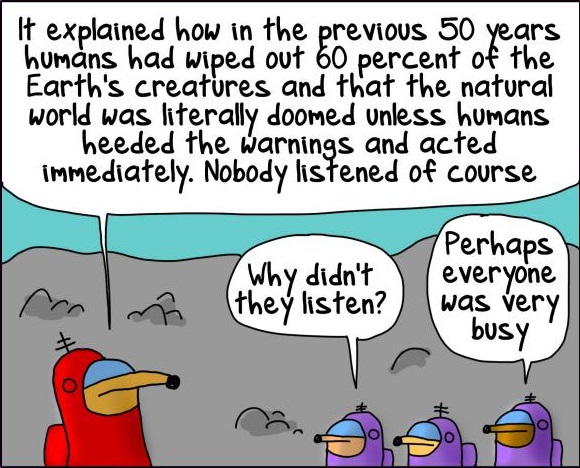

Why didn’t humanity save the planet? Perhaps they were busy

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.