Politics and pundits

The UK’s Conservative government, having realised that their mandate is worthless, seems to be in a panicked rush to try to get the voters to ignore any of the real issues. Instead, they say, we should be focussed on things like ludicrously-expensive and ineffective ways to handle asylum seekers and making life as hard as possible for their second-favourite scapegoat: trans and queer people.

The latest move in that second category seems likely to be a plan to, among other things, discourage teachers from talking about gender identity in schools, with children of any age. From the article I linked:

The BBC has not seen the new guidelines but a government source said they included plans to ban any children being taught about gender identity.

If asked, teachers will have to be clear gender ideology is contested.

Needless to say, such guidance is not likely to be well-received by teachers:

Pepe Di’Iasio, headteacher at a school in Rotherham, told Today that he believes pupils are being used “as a political football”.

Teachers “want well informed and evidence-based decisions”, he said, and not “politicised” guidance.

People and pupils

This shit isn’t harmless. Regardless of how strongly these kinds of regulations are enforced, they can have a devastating chilling effect in schools.

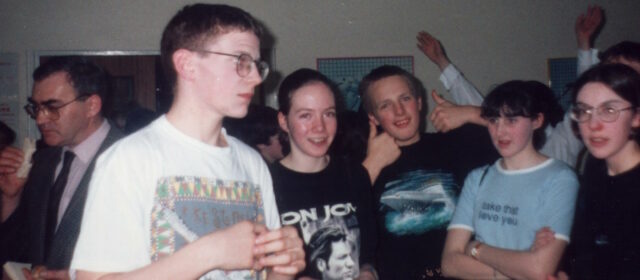

I speak from experience.

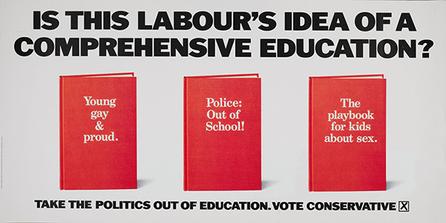

Most of my school years were under the shadow of Section 28. Like I predict for the new Conservative proposals, Section 28 superficially didn’t appear to have a major impact: nobody was ever successfully prosecuted under it, for example. But examining its effects in that way completely overlooks the effect it had on how teachers felt they had to work.

For example…

In around 1994, I witnessed a teacher turn a blind eye to homophobic bullying of a pupil by their peer, during a sex education class. Simultaneously, the teacher coolly dismissed the slurs of the bully, saying that we weren’t “talking about that in this class” and that the boy should “save his chatter for the playground”. I didn’t know about the regulations at the time: only in hindsight could I see that this might have been a result of Section 28. All I got to see at the time was a child who felt that his homophobic harassment of his classmate had the tacit endorsement of the teachers, so long as it didn’t take place in the classroom.

A gay friend, who will have been present but not involved in the above event, struggled with self-identity and relationships throughout his teenage years, only “coming out” as an adult. I’m confident that he could have found a happier, healthier life had he felt supported – or at the very least not-unwelcome – at school. I firmly believe that the long-running third-degree side-effects of Section 28 effectively robbed him of a decade of self-actualisation about his identity.

The long tail of those 1980s rules were felt long-after they were repealed. And for a while, it felt like things were getting better. But increasingly it feels like we’re moving backwards.

With general elections coming up later this year, it’ll soon be time to start quizzing your candidates on the issues that matter to you. Even (perhaps especially) if your favourite isn’t the one who wins, it can be easiest to get a politicians’ ear when they and their teams are canvassing for your vote; so be sure to ask pointed questions about the things you care about.

I hope that you’ll agree that not telling teachers to conceal from teenagers the diversity of human identity and experience is something worth caring about.

Update: Only a couple of hours after I posted this, the awesome folks (whom I’ve mentioned before) at the Vagina Museum tooted a thread about the long tail of Section 28. It’s well-worth a read.