Taking a photo of our kids isn’t too hard: their fascination with screens means you just have to switch to “selfie mode” and they lock-on to the camera like some kind of narcissist homing pigeon. Failing that, it’s easy enough to distract them with something that gets them to stay still for a few seconds and not just come out as a blur.

But compared to the generation that came before us, we have it really easy. When I was younger than our youngest is , I was obsessed with pressing buttons. So pronounced was my fascination that we had countless photos, as a child, of my face pressed so close to the lens that it’s impossible for the camera to focus, because I’d rushed over at the last second to try to be the one to push the shutter release button. I guess I just wanted to “help”?

In theory, exploiting this enthusiasm should have worked out well: my parents figured that if they just put me behind the camera, I could be persuaded to take a good picture of others. Unfortunately, I’d already fixated on another aspect of the photography experience: the photographer’s stance.

When people were taking picture of me, I’d clearly noticed that, in order to bring themselves down to my height (which was especially important given that I’d imminently try to be as close to the photographer as possible!) I’d usually see people crouching to take photos. And I must have internalised this, because I started doing it too.

Unfortunately, because I was shorter than most of my subjects, this resulted in some terrible framing, for example slicing off the tops of their heads or worse. And because this was a pre-digital age, there was no way to be sure exactly how badly I’d mucked-up the shot until days or weeks later when the film would be developed.

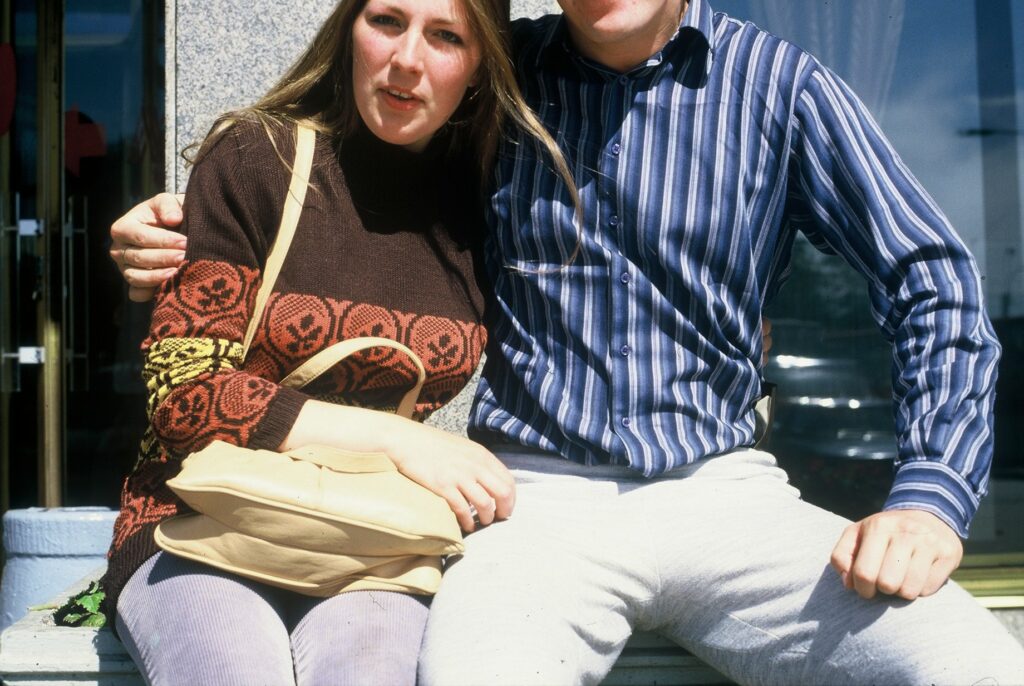

In an effort to counteract this framing issue, my dad (who was always keen for his young assistant to snap pictures of him alongside whatever article of public transport history he was most-interested in that day) at some point started crouching himself in photos. Presumably it proved easier to just duck when I did rather than to try to persuade me not to crouch in the first place.

As you look forward in time through these old family photos, though, you can spot the moment at which I learned to use a viewfinder, because people’s heads start to feature close to the middle of pictures.

Unfortunately, because I was still shorter than my subjects (especially if I was also crouching!), framing photos such that the subject’s face was in the middle of the frame resulted in a lot of sky in the pictures. Also, as you’ve doubtless seem above, I was completely incapable of levelling the horizon.

I’d like to think I’ve gotten better since, but based on the photo above… maybe the problem has been me, all along!

0 comments