I asked the younger child to “help” me calculate how much Yorkshire pudding batter to make for this Christmas dinner.

“Well,” he began, “I’m going to want FIVE Yorkshire puddings, soo…”

I’d never put much thought into it before but a slow cooker is basically the opposite of an air frier.

They’re both relatively small (compared to an oven) hot boxes for cooking food. But an air frier uses the small space to contain as much energy as possible in thir vicinity of the food, while the slow cooker aims to maintain as low a temperature as possible until the food finally cooks itself out of boredom.

Anyway, this is going to be pulled pork in like 8-10 hours. 😋

A quesapizza is a quesadilla, but made using pizza ingredients: not just cheese, but also a tomato sauce and maybe some toppings.

A quesapizza-pizza is a pizza… constructed using a quesapizza as its base. Quick to make and pretty delicious, it’s among my go-to working lunches.

The one you see above (and in the YouTube version of this video) is topped with a baked egg and chilli flakes. It might not be everybody’s idea of a great quesapizza-pizza, but I love mopping up the remainder of the egg yolk with the thick-stuffed cheese and tomato wraps. Mmm!

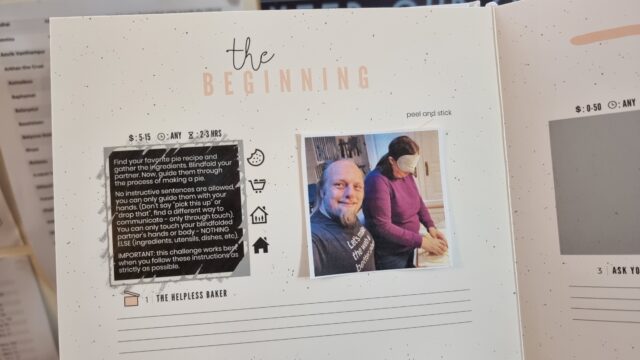

Ruth bought me a copy of The Adventure Challenge: Couples Edition, which is… well, it’s basically a book of 50 curious and unusual ideas for date activities. This week, for the first time, we gave it a go.

As a result, we spent this date night… baking a pie!

The book is written by Americans, but that wasn’t going to stop us from making a savoury pie. Of course, “bake a pie” isn’t much of a challenge by itself, which is why the book stipulates that:

We used this recipe for “mini creamy mushroom pies”. We chose to interpret the brief as permitting pre-prep to be done in accordance with the ingredients list: e.g. because the ingredients list says “1 egg, beaten”, we were allowed to break and beat the egg first, before blindfolding up.

This was a smart choice (breaking an egg while blindfolded, even under close direction, would probably have been especially stress-inducing!).

#JustSwitchThings

I really enjoyed this experience. It forced us into doing something different on date night (we have developed a bit of a pattern, as folks are wont to do), stretched our comfort zones, and left us with tasty tasty pies to each afterwards. That’s a win-win-win, in my book.

Plus, communication is sexy, and so anything that makes you practice your coupley-communication-skills is fundamentally hot and therefore a great date night activity.

So yeah: we’ll probably be trying some of the other ideas in the book, when the time comes.

Some of the categories are pretty curious, and I’m already wondering what other couples we know that’d be brave enough to join us for the “double date” chapter: four challenges for which you need a second dyad to hang out with? (I’m, like… 90% sure it’s not going to be swinging. So if we know you and you’d like to volunteer yourselves, go ahead!)

This evening I used leftover cocktail sausages to make teeny-tiny toads-in-the-hole (my kids say they should be called frogs-in-the-dip).

It worked out pretty well.

Micro-recipe:

1. Bake cocktail sausages (or veggie sausages, pictured) until barely done.

2. Meanwhile, make a batter (per every 6 sausages: use 50ml milk, 50g plain flour, 1 egg, pinch of salt).

3. Remove sausages from oven, then turn up to 220C.

4. Put a teaspoon of a high-temperature oil (e.g. vegetable, sunflower) into each pit of a cake/muffin tin, return to oven until almost at smoke point.

5. Add a sausage or two to each pit and return to the oven for a couple of minutes to come back up to temperature.

6. Add batter to each pit. It ought to sizzle when it hits the oil, if it’s hot enough. Return to the oven.

7. Remove when puffed-up and crisp. Serve with gravy and your favourite comfort food accompaniments.

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

I’m not a tea-drinker1. But while making a cuppa for Ruth this morning, a thought occurred to me and I can’t for a moment believe that I’m the first person to think of it:

What about a pressure-cooker, but for tea?2

Hear me out.

It’s been stressed how important it is that the water used to brew the tea is 100℃, or close to it possible. That’s the boiling point of water at sea level, so you can’t really boil your kettle hotter than that or else the water runs away to pursue a new life as a cloud.

That temperature is needed to extract the flavours, apparently3. And that’s why you can’t get a good cup of tea at high altitudes, I’m told: by the time you’re 3000 metres above sea level, water boils at around 90℃ and most British people wilt at their inability to make a decent cuppa4.

It’s a question of pressure, right? Increase the pressure, and you increase the boiling point, allowing water to reach a higher temperature before it stops being a liquid and starts being a gas. Sooo… let’s invent something!

I’m thinking a container about the size of a medium-sized Thermos flask or a large keep-cup – you need thick walls to hold pressure, obviously – with a safety valve and a heating element, like a tiny version of a modern pressure cooker. The top half acts as the lid, and contains a compartment into which you put your teabag or loose leaves (optionally in an infuser). After being configured from the front panel, the water gets heated to a specified temperature – which can be above the ambient boiling point of water owing to the pressurisation – at which point the tea is released from the upper half. The temperature is maintained for a specified amount of time and then the user is notified so they can release the pressure, open the top, lift out the inner cup, remove the teabag, and enjoy their beverage.

This isn’t just about filling the niche market of “dissatisfied high-altitude tea drinkers”. Such a device would also be suitable for other folks who want a controlled tea experience. You could have it run on a timer and make you tea at a particular time, like a teasmade. You can set the temperature lower for a controlled brew of e.g. green tea at 70℃. But there’s one other question that a device like this might have the capacity to answer:

What is the ideal temperature for making black tea?

We’re told that it’s 100℃, but that’s probably an assumption based on the fact that that’s as hot as your kettle can get water to go, on account of physics. But if tea is bad when it’s brewed at 90℃ and good when it’s brewed at 100℃… maybe it’s even better when it’s brewed at 110℃!

A modern pressure cooker can easily maintain a liquid water temperature of 120℃, enabling excellent extraction of flavour into water (this is why a pressure cooker makes such excellent stock).

I’m not the person to answer this question, because, as I said: I’m not a tea drinker. But surely somebody’s tried this5? It shouldn’t be too hard to retrofit a pressure cooker lid with a sealed compartment that releases, even if it’s just on a timer, to deposit some tea into some superheated water?

Because maybe, just maybe, superheated water makes better tea. And if so, there’s a possible market for my proposed device.

1 I probably ought to be careful confessing to that or they’ll strip my British citizenship.

2 Don’t worry, I know better than to suggest air-frying a cup of ta. What kind of nutter would do that?

3 Again, please not that I’m not a tea-drinker so I’m not really qualified to comment on the flavour of tea at all, let alone tea that’s been brewed at too-low a temperature.

4 Some high-altitude tea drinkers swear by switching from black tea to green tea, white tea, or oolong, which apparently release their aromatics at lower temperatures. But it feels like science, not compromise, ought to be the solution to this problem.

5 I can’t find the person who’s already tried this, if they exist, but maybe they’re out there somewhere?

Do you think the 80s/90s advertisement campaign for Sarson’s vinegar – “Don’t say vinegar, say Sarson’s” – ever worked?

Like: have you ever heard anybody ask you to “pass the Sarson’s”?

I swear I’m onto something with this idea: Scottish-Mexican fusion cookery. Hear me out.

It started on the last day of our trip to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2012 when, in an effort to use up our self-catering supplies, JTA suggested (he later claimed this should have been taken as a joke) haggis tacos. Ruth and I ate a whole bunch of them and they were great.

In Scotland last week (while I wasn’t climbing mountains and thinking of my father), Ruth and I came up with our second bit of Scottish-Mexican fusion food: tattie scone quesadillas. Just sandwich some cheese and anything else you like between tattie scones and gently fry in butter.

We’re definitely onto something. But what to try next? How about…

Earlier this month, I made my first attempt at cooking pizza in an outdoor wood-fired oven. I’ve been making pizza for years: how hard can it be?

It turned out: pretty hard. The oven was way hotter than I’d appreciated and I burned a few crusts. My dough was too wet to slide nicely off my metal peel (my wooden peel disappeared, possibly during my house move last year), and my efforts to work-around this by transplanting cookware in and out of the oven quickly lead to flaming Teflon and a shattered pizza stone. I set up the oven outside the front door and spent all my time running between the kitchen (at the back of the house) and the front door, carrying hot tools, while hungry children snapped at my ankles. In short: mistakes were made.

I suspect that cooking pizza in a wood-fired oven is challenging in the same way that driving a steam locomotive is. I’ve not driven one, except in simulators, but it seems like you’ve got a lot of things to monitor at the same time. How fast am I going? How hot is the fire? How much fuel is in it? How much fuel is left? How fast is it burning through it? How far to the next station? How’s the water pressure? Oh fuck I forget to check on the fire while I was checking the speed…

So it is with a wood-fired pizza oven. If you spend too long preparing a pizza, you’re not tending the fire. If you put more fuel on the fire, the temperature drops before it climbs again. If you run several pizzas through the oven back-to-back, you leech heat out of the stone (my oven’s not super-thick, so it only retains heat for about four consecutive pizzas then it needs a few minutes break to get back to an even temperature). If you put a pizza in and then go and prepare another, you’ve got to remember to come back 40 seconds later to turn the first pizza. Some day I’ll be able to manage all of those jobs alone, but for now I was glad to have a sous-chef to hand.

Today I was cooking out amongst the snow, in a gusty crosswind, and I learned something else new. Something that perhaps I should have thought of already: the angle of the pizza oven relative to the wind matters! As the cold wind picked up speed, its angle meant that it was blowing right across the air intake for my fire, and it was sucking all of the heat out of the back of the oven rather than feeding the flame and allowing the plasma and smoke to pass through the top of the oven. I rotated the pizza oven so that the air blew into rather than across the oven, but this fanned the flames and increased fuel consumption, so I needed to increase my refuelling rate… there are just so many variables!

The worst moment of the evening was probably when I took a bite out of a pizza that, it turned out, I’d shunted too-deep into the oven and it had collided with the fire. How do I know? Because I bit into a large chunk of partially-burned wood. Not the kind of smoky flavour I was looking for.

But apart from that, tonight’s pizza-making was a success. Cooking in a sub-zero wind was hard, but with the help of my excellent sous-chef we churned out half a dozen good pizzas (and a handful of just-okay pizzas), and more importantly: I learned a lot about the art of cooking pizza in a box of full of burning wood. Nice.

Clearly those closest to me know me well, because for my birthday today I received a beautiful (portable: it packs into a bag!) wood-fired pizza oven, which I immediately assembled, test-fired, cleaned, and prepped with the intention of feeding everybody some homemade pizza using some of Robin‘s fabulous bread dough, this evening.

Fuelled up with wood pellets the oven was a doddle to light and bring up to temperature. It’s got a solid stone slab in the base which looked like it’d quickly become ideal for some fast-cooked, thin-based pizzas. I was feeling good about the whole thing.

But then it all began to go wrong.

If you’re going to slip pizzas onto hot stone – especially using a light, rich dough like this one – you really need a wooden peel. I own a wooden peel… somewhere: I haven’t seen it since I moved house last summer. I tried my aluminium peel, but it was too sticky, even with a dusting of semolina or a light layer of oil. This wasn’t going to work.

I’ve got some stone slabs I use for cooking fresh pizza in a conventional oven, so I figured I’d just preheat them, assemble pizzas directly on them, and shunt the slabs in. Easy as (pizza) pie, right?

This oven is hot. Seriously hot. Hot enough to cook the pizza while I turned my back to assemble the next one, sure. But also hot enough to crack apart my old pizza stone. Right down the middle. It normally never goes hotter than the 240ºC of my regular kitchen oven, but I figured that it’d cope with a hotter oven. Apparently not.

So I changed plan. I pulled out some old round metal trays and assembled the next pizza on one of those. I slid it into the oven and it began to cook: brilliant! But no sooner had I turned my back than… the non-stick coating on the tray caught fire! I didn’t even know that was a thing that could happen.

Those first two pizzas may have each cost me a piece of cookware, but they tasted absolutely brilliant. Slightly coarse, thick, yeasty dough, crisped up nicely and with a hint of woodsmoke.

But I’m not sure that the experience was worth destroying a stone slab and the coating of a metal tray, so I’ll be waiting until I’ve found (or replaced) my wooden peel before I tangle with this wonderful beast again. Lesson learned.