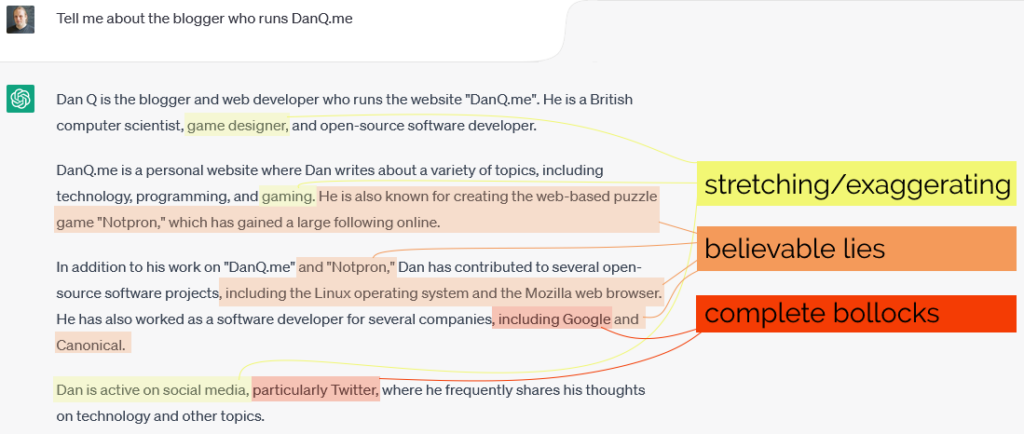

This blog post is also available as a video. Would you prefer to watch/listen to me tell you about the video game that had the biggest impact on my life?

Of all of the videogames I’ve ever played, perhaps the one that’s had the biggest impact on my life1 was: Werewolves and (the) Wanderer.2

This simple text-based adventure was originally written by Tim Hartnell for use in his 1983 book Creating Adventure Games on your Computer. At the time, it was common for computing books and magazines to come with printed copies of program source code which you’d need to re-type on your own computer, printing being significantly many orders of magnitude cheaper than computer media.3

I’d been working my way through the operating manual for our microcomputer, trying to understand it all.5

![Scan of a ring-bound page from a technical manual. The page describes the use of the "INPUT" command, saying "This command is used to let the computer know that it is expecting something to be typed in, for example, the answer to a question". The page goes on to provide a code example of a program which requests the user's age and then says "you look younger than [age] years old.", substituting in their age. The page then explains how it was the use of a variable that allowed this transaction to occur.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2023/07/cpc664-manual-input-command.png)

[ENTER] at the end of each line.

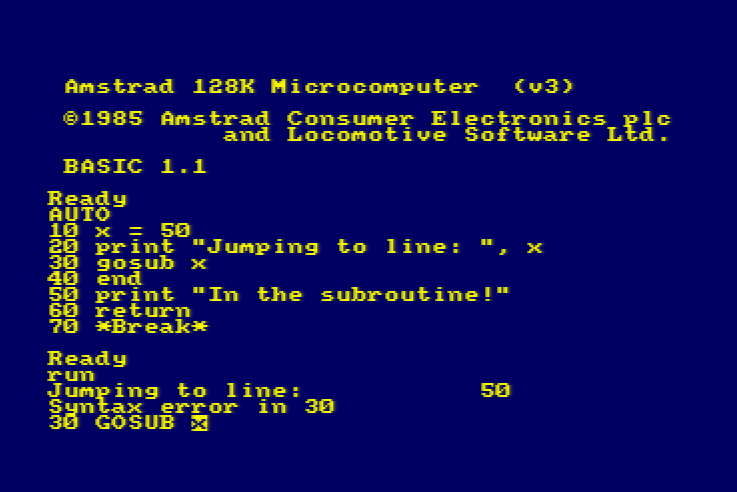

In particular, I found myself comparing Werewolves to my first attempt at a text-based adventure. Using what little I’d grokked of programming so far, I’d put together

a series of passages (blocks of PRINT statements6)

with choices (INPUT statements) that sent the player elsewhere in the story (using, of course, the long-considered-harmful GOTO statement), Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style.

Werewolves was… better.

Werewolves and Wanderer was my first lesson in how to structure a program.

Let’s take a look at a couple of segments of code that help illustrate what I mean (here’s the full code, if you’re interested):

10 REM WEREWOLVES AND WANDERER 20 GOSUB 2600:REM INTIALISE 30 GOSUB 160 40 IF RO<>11 THEN 30 50 PEN 1:SOUND 5,100:PRINT:PRINT "YOU'VE DONE IT!!!":GOSUB 3520:SOUND 5,80:PRINT "THAT WAS THE EXIT FROM THE CASTLE!":SOUND 5,200 60 GOSUB 3520 70 PRINT:PRINT "YOU HAVE SUCCEEDED, ";N$;"!":SOUND 5,100 80 PRINT:PRINT "YOU MANAGED TO GET OUT OF THE CASTLE" 90 GOSUB 3520 100 PRINT:PRINT "WELL DONE!" 110 GOSUB 3520:SOUND 5,80 120 PRINT:PRINT "YOUR SCORE IS"; 130 PRINT 3*TALLY+5*STRENGTH+2*WEALTH+FOOD+30*MK:FOR J=1 TO 10:SOUND 5,RND*100+10:NEXT J 140 PRINT:PRINT:PRINT:END ... 2600 REM INTIALISE 2610 MODE 1:BORDER 1:INK 0,1:INK 1,24:INK 2,26:INK 3,18:PAPER 0:PEN 2 2620 RANDOMIZE TIME 2630 WEALTH=75:FOOD=0 2640 STRENGTH=100 2650 TALLY=0 2660 MK=0:REM NO. OF MONSTERS KILLED ... 3510 REM DELAY LOOP 3520 FOR T=1 TO 900:NEXT T 3530 RETURN

...) have been added for readability/your convenience.

What’s interesting about the code above? Well…

- The code for “what to do when you win the game” is very near the top. “Winning” is the default state. The rest of the adventure exists to obstruct that. In a language with enforced line numbering and no screen editor7, it makes sense to put fixed-length code at the top… saving space for the adventure to grow below.

- Two subroutines are called (the

GOSUBstatements):- The first sets up the game state: initialising the screen (

2610), the RNG (2620), and player characteristics (2630–2660). This also makes it easy to call it again (e.g. if the player is given the option to “start over”). This subroutine goes on to set up the adventure map (more on that later). - The second starts on line

160: this is the “main game” logic. After it runs, each time, line40checksIF RO<>11 THEN 30. This tests whether the player’s location (RO) is room 11: if so, they’ve exited the castle and won the adventure. Otherwise, flow returns to line30and the “main game” subroutine happens again. This broken-out loop improving the readability and maintainability of the code.8

- The first sets up the game state: initialising the screen (

- A common subroutine is the “delay loop” (line

3520). It just counts to 900! On a known (slow) processor of fixed speed, this is a simpler way to put a delay in than relying on a real-time clock.

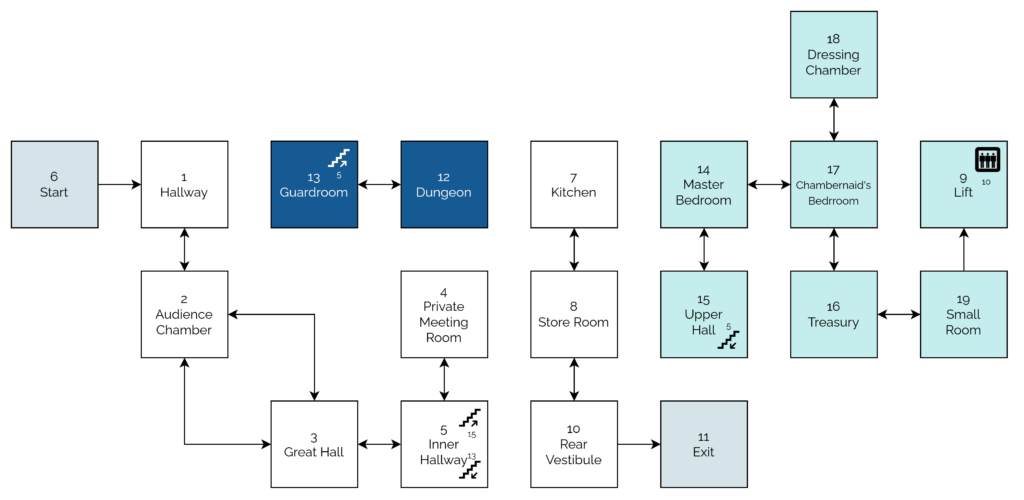

The game setup gets more interesting still when it comes to setting up the adventure map. Here’s how it looks:

2680 REM SET UP CASTLE 2690 DIM A(19,7):CHECKSUM=0 2700 FOR B=1 TO 19 2710 FOR C=1 TO 7 2720 READ A(B,C):CHECKSUM=CHECKSUM+A(B,C) 2730 NEXT C:NEXT B 2740 IF CHECKSUM<>355 THEN PRINT "ERROR IN ROOM DATA":END ... 2840 REM ALLOT TREASURE 2850 FOR J=1 TO 7 2860 M=INT(RND*19)+1 2870 IF M=6 OR M=11 OR A(M,7)<>0 THEN 2860 2880 A(M,7)=INT(RND*100)+100 2890 NEXT J 2910 REM ALLOT MONSTERS 2920 FOR J=1 TO 6 2930 M=INT(RND*18)+1 2940 IF M=6 OR M=11 OR A(M,7)<>0 THEN 2930 2950 A(M,7)=-J 2960 NEXT J 2970 A(4,7)=100+INT(RND*100) 2980 A(16,7)=100+INT(RND*100) ... 3310 DATA 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 3320 DATA 1, 3, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0 3330 DATA 2, 0, 5, 2, 0, 0, 0 3340 DATA 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 3350 DATA 4, 0, 0, 3, 15, 13, 0 3360 DATA 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0 3370 DATA 0, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 3380 DATA 7, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 3390 DATA 0, 19, 0, 8, 0, 8, 0 3400 DATA 8, 0, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0 3410 DATA 0, 0, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0 3420 DATA 0, 0, 0, 13, 0, 0, 0 3430 DATA 0, 0, 12, 0, 5, 0, 0 3440 DATA 0, 15, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0 3450 DATA 14, 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0 3460 DATA 17, 0, 19, 0, 0, 0, 0 3470 DATA 18, 16, 0, 14, 0, 0, 0 3480 DATA 0, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 3490 DATA 9, 0, 16, 0, 0, 0, 0

DATA statements form a “table”.

What’s this code doing?

- Line

2690defines an array (DIM) with two dimensions9 (19 by 7). This will store room data, an approach that allows code to be shared between all rooms: much cleaner than my first attempt at an adventure with each room having its ownINPUThandler. - The two-level loop on lines

2700through2730populates the room data from theDATAblocks. Nowadays you’d probably put that data in a separate file (probably JSON!). Each “row” represents a room, 1 to 19. Each “column” represents the room you end up at if you travel in a given direction: North, South, East, West, Up, or Down. The seventh column – always zero – represents whether a monster (negative number) or treasure (positive number) is found in that room. This column perhaps needn’t have been included: I imagine it’s a holdover from some previous version in which the locations of some or all of the treasures or monsters were hard-coded. - The loop beginning on line

2850selects seven rooms and adds a random amount of treasure to each. The loop beginning on line2920places each of six monsters (numbered-1through-6) in randomly-selected rooms. In both cases, the start and finish rooms, and any room with a treasure or monster, is ineligible. When my 8-year-old self finally deciphered what was going on I was awestruck at this simple approach to making the game dynamic. - Rooms 4 and 16 always receive treasure (lines

2970–2980), replacing any treasure or monster already there: the Private Meeting Room (always worth a diversion!) and the Treasury, respectively. - Curiously, room 9 (the lift) defines three exits, even though it’s impossible to take an action in this location: the player teleports to room 10 on arrival! Again, I assume this is vestigal code from an earlier implementation.

- The “checksum” that’s tested on line

2740is cute, and a younger me appreciated deciphering it. I’m not convinced it’s necessary (it sums all of the values in theDATAstatements and expects355to limit tampering) though, or even useful: it certainly makes it harder to modify the rooms, which may undermine the code’s value as a teaching aid!

Something you might notice is missing is the room descriptions. Arrays in this language are strictly typed: this array can only contain integers and not strings. But there are other reasons: line length limitations would have required trimming some of the longer descriptions. Also, many rooms have dynamic content, usually based on random numbers, which would be challenging to implement in this way.

As a child, I did once try to refactor the code so that an eighth column of data specified the line number to which control should pass to display the room description. That’s

a bit of a no-no from a “mixing data and logic” perspective, but a cool example of metaprogramming before I even knew it! This didn’t work, though: it turns out you can’t pass a

variable to a Locomotive BASIC GOTO or GOSUB. Boo!10

Werewolves and Wanderer has many faults11. But I’m clearly not the only developer whose early skills were honed and improved by this game, or who hold a special place in their heart for it. Just while writing this post, I discovered:

- A moderately-faithful Inform reimplementation

- A less-faithful semi-graphical adaptation

- A C# reimplementation with a web interface (video)

- An ongoing livestreamed effort to reimplement as a Sierra-style point-and-click adventure

- An Applesoft BASIC implementation which includes a dynamically-revealed map

- A C reimplementation with a high score table

- A somewhat-faithful reimplementation in Rust (playable online via WebAssembly)

- A very accurate rendition in Python

- A Ruby/Python microservices-based implementation

- Many, many people commenting on the above or elsewhere about how instrumental the game was in their programming journey, too.

A decade or so later, I’d be taking my first steps as a professional software engineer. A couple more decades later, I’m still doing it.

And perhaps that adventure -the one that’s occupied my entire adult life – was facilitated by this text-based one from the 1980s.

Footnotes

1 The game that had the biggest impact on my life, it might surprise you to hear, is not among the “top ten videogames that stole my life” that I wrote about almost exactly 16 years ago nor the follow-up list I published in its incomplete form three years later. Turns out that time and impact are not interchangable. Who knew?

2 The game is variously known as Werewolves and Wanderer, Werewolves and

Wanderers, or Werewolves and the

Wanderer. Or, on any system I’ve been on, WERE.BAS, WEREWOLF.BAS, or WEREWOLV.BAS, thanks to the CPC’s eight-point-three filename limit.

3 Additionally, it was thought that having to undertake the (painstakingly tiresome) process of manually re-entering the source code for a program might help teach you a little about the code and how it worked, although this depended very much on how readable the code and its comments were. Tragically, the more comprehensible some code is, the more long-winded the re-entry process.

4 The CPC’s got a fascinating history in its own right, but you can read that any time.

5 One of my favourite features of home microcomputers was that seconds after you turned them on, you could start programming. Your prompt was an interface to a programming language. That magic had begun to fade by the time DOS came to dominate (sure, you can program using batch files, but they’re neither as elegant nor sophisticated as any BASIC dialect) and was completely lost by the era of booting directly into graphical operating systems. One of my favourite features about the Web is that it gives you some of that magic back again: thanks to the debugger in a modern browser, you can “tinker” with other people’s code once more, right from the same tool you load up every time. (Unfortunately, mobile devices – which have fast become the dominant way for people to use the Internet – have reversed this trend again. Try to View Source on your mobile – if you don’t already know how, it’s not an easy job!)

6 In particular, one frustration I remember from my first text-based adventure was that I’d been unable to work around Locomotive BASIC’s lack of string escape sequences – not that I yet knew what such a thing would be called – in order to put quote marks inside a quoted string!

7 “Screen editors” is what we initially called what you’d nowadays call a “text editor”: an application that lets you see a page of text at the same time, move your cursor about the place, and insert text wherever you feel like. It may also provide features like copy/paste and optional overtyping. Screen editors require more resources (and aren’t suitable for use on a teleprinter) compared to line editors, which preceeded them. Line editors only let you view and edit a single line at a time, which is how most of my first 6 years of programming was done.

8 In a modern programming language, you might use while true or similar for a

main game loop, but this requires pushing the “outside” position to the stack… and early BASIC dialects often had strict (and small, by modern standards) limits on stack height that

would have made this a risk compared to simply calling a subroutine from one line and then jumping back to that line on the next.

9 A neat feature of Locomotive BASIC over many contemporary and older BASIC dialects was its support for multidimensional arrays. A common feature in modern programming languages, this language feature used to be pretty rare, and programmers had to do bits of division and modulus arithmetic to work around the limitation… which, I can promise you, becomes painful the first time you have to deal with an array of three or more dimensions!

10 In reality, this was rather unnecessary, because the ON x GOSUB command

can – and does, in this program – accept multiple jump points and selects the one

referenced by the variable x.

11 Aside from those mentioned already, other clear faults include: impenetrable controls unless you’ve been given instuctions (although that was the way at the time); the shopkeeper will penalise you for trying to spend money you don’t have, except on food, presumably as a result of programmer laziness; you can lose your flaming torch, but you can’t buy spares in advance (you can pay for more, and you lose the money, but you don’t get a spare); some of the line spacing is sometimes a little wonky; combat’s a bit of a drag; lack of feedback to acknowledge the command you enterted and that it was successful; WHAT’S WITH ALL THE CAPITALS; some rooms don’t adequately describe their exits; the map is a bit linear; etc.