The phone signal is so shit at this year’s 3Camp venue that I’ve had to climb a hill to take a call from a lawyer (whom I’m speaking to about my recent redundancy). Nice to be outdoors, though!

Author: Dan Q

Scots Fire Brigade Union demand new legal protections for people with more than one romantic partner

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

In the fight for equal representation for polyamorous relationships, polyamorists may have a strange and unlikely ally in… the Scottish Fire Brigade Union:

Scotland’s Fire Brigade Union (FBU) has been blasted after calling for more legal protections for Scots who have more than one romantic partner. Members of the group, which is meant to campaign to protect firefighters, want to boost the legal rights of polyamorous people.

…

I love that a relatively mainstream union is taking seriously this issue that affects only a tiny minority of the population, but I have to wonder… why? What motivates such interest? Are Scottish fire bridades all secretly in a big happy polycule together? (That’d be super cute.)

Anyway: good for them, good for us, good all round at a time with a bit of a shortage of good news.

Dan Q found GC1DH7W Knipe Scar – On the Edge

This checkin to GC1DH7W Knipe Scar - On the Edge reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

A swift uphill scramble for my friend and fellow volunteer John and I, before dinner. We’re staying in a nearby farmhouse for a week of volunteer work, writing software to help charities. Beautiful view from the summit this evening! SL, TNLN, TFTC!

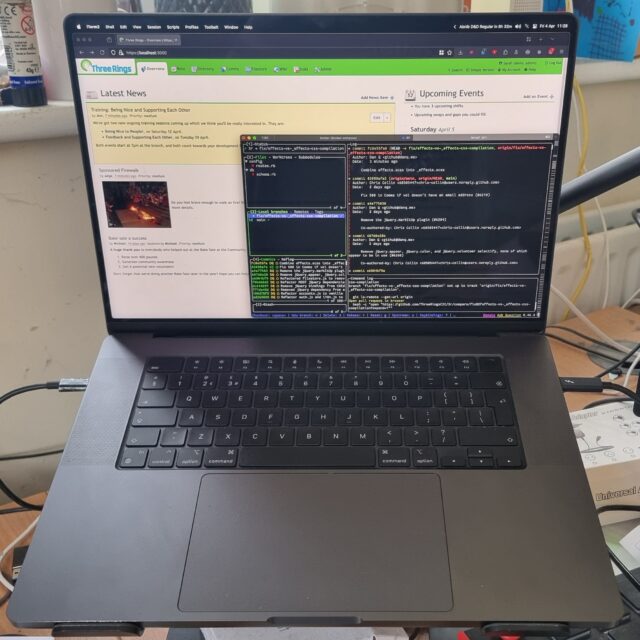

3Camp 2025

I’m off for a week of full-time volunteering with Three Rings at 3Camp, our annual volunteer hack week: bringing together our distributed team for some intensive in-person time, working to make life better for charities around the world.

And if there’s one good thing to come out of me being suddenly and unexpectedly laid-off two days ago, it’s that I’ve got a shiny new laptop to do my voluntary work on (Automattic have said that I can keep it).

Dan Q found GC97N3H Lodge Hill C & D

This checkin to GC97N3H Lodge Hill C & D reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

QEF as a cache-and-dash. This afternoon, owing to Some Plot, I needed to go speak to a lawyer in Abingdon, and rewarded myself on a successful mission by visiting this cache on my way home. TFTC!

Redundant

Apparently Automattic are laying off around one in six of their workforce. And I’m one of the unlucky ones.

Anybody remote hiring for a UK-based full-stack web developer (in a world that doesn’t seem to believe that full-stack developers exist anymore) with 25+ years professional experience, specialising in PHP, Ruby, JS, HTML, CSS, devops, and about 50% of CMSes you’ve ever heard of (and probably some you haven’t)… with a flair for security, accessibility, standards-compliance, performance, and DexEx?

CV at: https://danq.me/cv

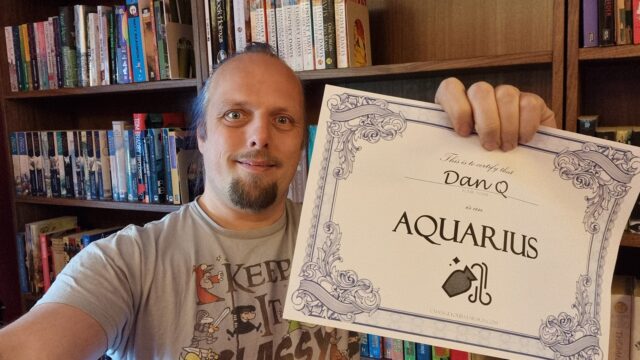

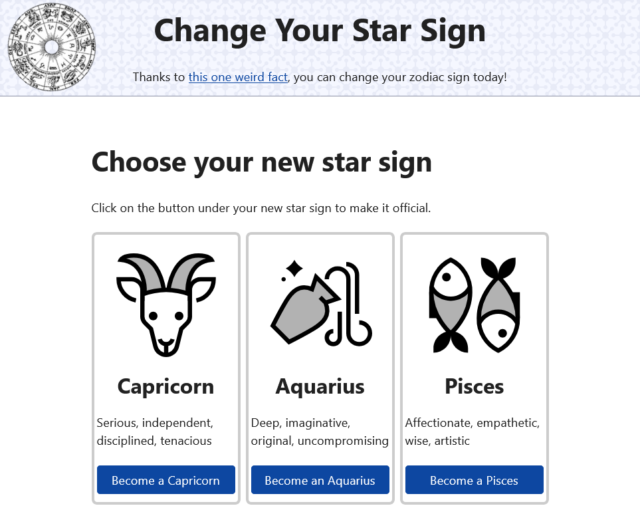

Change Your Star Sign

My star sign is Aquarius. Aquarians are, according to tradition: deep, imaginative, original, and uncompromising. That sounds like a pretty good description of me, right?

Now some of you might be thinking, “Hang on, wasn’t Dan born very close to the start of the year, and wouldn’t that make him a Capricorn, not an Aquarius?” I can understand why you’d think that.

And while it’s true that I was assigned the star sign of Capricorn at my birth, it doesn’t really represent me very well. Capricorns are, we’re told, serious, disciplined, and good with money. Do any of those things remotely sound like me? Not so much.

So many, many years ago I changed my star sign to Aquarius (I can’t remember exactly when, but I’d done it a long while before I wrote the linked blog post, which in turn is over 14 years old…).

I’ve been told that it’s not possible to change one’s star sign.

But really: who has the right to tell you what your place in the zodiac is, really? Just you.

And frankly, people telling you who you can and can’t be is so last millennium. By now, there’s really no excuse for not accepting somebody’s identity, whether it’s for something as trivial as their star sign… or as important as their gender, sexuality, or pronouns.

All of which is to say: I’ve launched a(nother) stupid website, ChangeYourStarSign.com. Give it a go!

It’s lightweight, requires no JS or cookies, does no tracking, and can run completely offline or be installed to your device, and it makes it easier than ever for you to change your star sign. Let’s be honest: it was pretty easy anyway – just decide what your new star sign is – but if you’d rather have a certificate to prove it, this site’s got you covered.

Whether you change your star sign to represent you better, to sidestep an unfortuitous horoscope (or borrow a luckier one), or for some other reason, I’d love to hear what you change it to and how you get on with it. What’s your new star sign?

My on-again-off-again relationship with AI assistants

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Sean McPherson, whom I’ve been following ever since he introduced me to the Five-Room Dungeons concept, said:

…

There is a lot of smoke in the work-productivity AI space. I believe there is (probably) fire there somewhere. But I haven’t been able to find it.

…

I find AI assistants useful, just less so than other folks online. I’m glad to have them as an option but am still on the lookout for a reason to pay $20/month for a premium plan. If that all resonants and you have some suggestions, please reach out. I can be convinced!

…

I’m in a similar position to Sean. I enjoy Github Copilot, but not enough that I would pay for it out of my own pocket (like him, I get it for free, in my case because I’m associated with a few eligible open source projects). I’ve been experimenting with Cursor and getting occasionally good results, but again: I wouldn’t have paid for it myself (but my employer is willing to do so, even just for me to “see if it’s right for me”, which is nice).

I think this is all part of what I was complaining about yesterday, and what Sean describes as “a lot of smoke”. There’s so much hype around AI technologies that it takes real effort to see through it all to the actual use-cases that exist in there, somewhere. And that’s the effort required before you even begin to grapple with questions of cost, energy usage, copyright ethics and more. It’s a really complicated space!

Unacceptable language

8-year-old, angry: Give me that fucking thing right now!

Me: [Child’s name]! That’s not an acceptable way to ask for something!

8-year-old, calmer: Sorry. PLEASE can you give me that fucking thing?

Bored of it

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

Every article glorifying it.

Every article vilifying it.

Every pub conversation winding up talking about it.

People incessantly telling you how they use it.

I feel dirty using it.

You know what I’m talking about, even though I’ve not mentioned it.

…

If you don’t know what “it” is without the rest of the context, maybe read the rest of Paul’s poem. I’ll wait.

As you might know, I remain undecided on the value of GenAI. It produces decidedly middle-of-the-road output, which while potentially better than the average human isn’t better than the average specialist in any particular area. It’s at risk of becoming a snake-eating-its-own-tail as slop becomes its own food. It “hallucinates”, of course. And I’m concerned about how well it acts as a teacher to potential new specialists in their field.

There are things it does well-enough, and much faster than a human, that it’s certainly not useless: indeed, I’ve used it for a variety of things from the practical to the silly to the sneaky, and many more activities besides 1. I routinely let an LLM suggest autocompletion, and I’ve experimented with having it “code for me” (with the caveat that I’m going to end up re-reading it all anyway!).

But I’m still not sure whether that, on the balance of things, GenAI represents a net benefit. Time will tell, I suppose.

And like Paul, I’m sick of “the pervasive, all encompassing nature of it”. I never needed AI integration in NOTEPAD.EXE before, and I still don’t need it now! Not

everything needs to be about AI, just because it’s the latest hip thing. Remember when everybody was talking about how everything belonged on the blockchain (it doesn’t): same

energy. Except LLMs are more-accessible to more-people, thanks to things like ChatGPT, so the signal-to-noise ratio in the hype machine is much, much worse. Nowadays, you actually have

to put significant effort in if you want to find the genuinely useful things that AI does, amongst all of the marketing crap that surrounds it.

Footnotes

1 You’ll note that I specifically don’t make use of it for writing any content for this blog: the hallucinations and factual errors you see here are genuine organic human mistakes!

To-go pint

Note #26217

Istanbul decompression

It wasn’t until I made time for myself to get out into the countryside near my home and take the dog for a walk that I realised how much stress I’d been putting myself under during my team meetup, this week.

Istanbul was enjoyable and fascinating, and I love my team, but I always forget until after the fact how much a few days worth of city crowds can make me feel anxious and trapped.

It’s good to get a mile or two from the nearest other human and decompress!

Delivery Songs

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Here in the UK, ice cream vans will usually play a tune to let you know they’re set up and selling1. So when you hear Greensleeves (or, occasionally, Waltzing Matilda), you know it’s time to go and order yourself a ninety-nine.

Imagine my delight, then, when I discover this week that ice cream vans aren’t the only services to play such jaunty tunes! I was sat with work colleagues outside İlter’s Bistro on Meşrutiyet Cd. in Istanbul, enjoying a beer, when a van carrying water pulled up and… played a little song!

And then, a few minutes later – as if part of the show for a tourist like me – a flatbed truck filled with portable propane tanks pulled up. Y’know, the kind you might use to heat a static caravan. Or perhaps a gas barbeque if you only wanted to have to buy a refill once every five years. And you know what: it played a happy little jingle, too. Such joy!

My buddy Cem, who’s reasonably local to the area, told me that this was pretty common practice. The propane man, the water man, etc. would all play a song when they arrived in your neighbourhood so that you’d be reminded that, if you hadn’t already put your empties outside for replacement, now was the time!

And then Raja, another member of my team, observed that in his native India, vegetable delivery trucks also play a song so you know they’re arriving. Apparently the tune they play is as well-standardised as British ice cream vans are. All of the deliveries he’s aware of across his state of Chennai play the same piece of music, so that you know it’s them.

It got me thinking: what other delivery services might benefit from a recognisable tune?

- Bin men: I’ve failed to put the bins out in time frequently enough, over the course of my life, that a little jingle to remind me to do so would be welcome4! (My bin men often don’t come until after I’m awake anyway, so as long as they don’t turn the music on until after say 7am they’re unlikely to be a huge inconvenience to anybody, right?) If nothing else, it’d cue me in to the fact that they were passing so I’d remember to bring the bins back in again afterwards.

- Fish & chip van: I’ve never made use of the mobile fish & chip van that tours my village once a week, but I might be more likely to if it announced its arrival with a recognisable tune.

- Milkman: I’ve a bit of a gripe with our milkman. Despite promising to deliver before 07:00 each morning, they routinely turn up much later. It’s particularly troublesome when they come at about 08:40 while I’m on the school run, which breaks my routine sufficiently that it often results in the milk sitting unseen on the porch until I think to check much later in the day. Like the bin men, it’d be a convenience if, on running late, they at least made their presence in my village more-obvious with a happy little ditty!

- Emergency services: Sirens are boring. How about if blue light services each had their own song. Perhaps something thematic? Instead of going nee-naw-nee-naw, you’d hear, say, de-do-do-do-de-dah-dah-dah and instantly know that you were hearing The Police.

- Evri: Perhaps there’s an appropriate piece of music that says “the courier didn’t bother to ring your doorbell, so now your parcel’s hidden in your recycling box”? Just a thought.

Anyway: the bottom line is that I think there’s an untapped market for jolly little jingles for all kinds of delivery services, and Turkey and India are clearly both way ahead of the UK. Let’s fix that!

Footnotes

1 It’s not unheard of for cruel clever parents to try to teach their young

children that the ice cream van plays music only to let you know it’s sold out of ice cream. A devious plan, although one I wasn’t smart (or evil?) enough to try for

myself.

2 The official line from the government is that the piped water is safe to drink, but every single Turkish person I spoke to on the subject disagreed and said that I shouldn’t listen to… well, most of what the government says. Having now witnessed first-hand the disparity between the government’s line on the unrest following the arrest of the opposition’s presidential candidate and what’s actually happening on the ground, I’m even more inclined to listen to the people.

3 My gas delivery man should also have his own song, of course. Perhaps an instrumental cover of Burn Baby Burn?

4 Perhaps bin men could play Garbage Truck by Sex Bob-Omb/Beck? That seems kinda fitting. Although definitely not what you want to be woken up with if they turn the speakers on too early…

Dan Q found GC7B9C6 Heykel&Boğaz/Sculpture & Bosphorus- Virtual Reward

This checkin to GC7B9C6 Heykel&Boğaz/Sculpture & Bosphorus- Virtual Reward reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

As others have observed, this is a bit challenging right now owing to the hoardings that have been erected in the way. But like others, I found a gap in the fence through which I was able to photograph the sculpture (while holding up a piece of paper with the geocaching logo and my username, to prevent reuse!). TFTC!