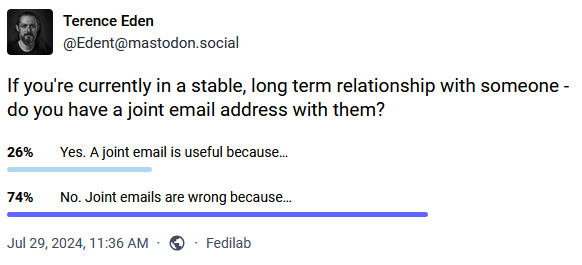

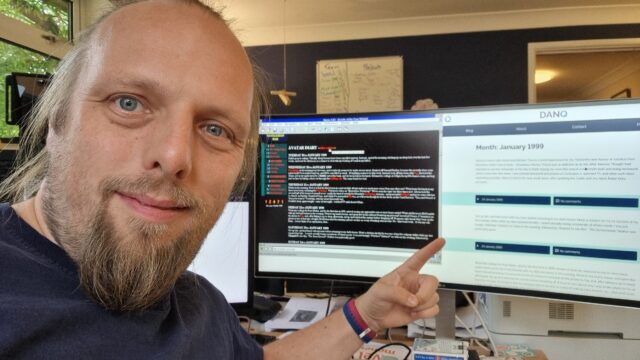

Terence Eden, who’s apparently inspiring several posts this week, recently shared a way to attach a hook to WordPress’s

get_the_post_thumbnail() function in order to remove the extraneous “closing mark” from the (self-closing in HTML) <img> element.

By default, WordPress outputs e.g. <img src="..." />, where <img src="..."> would suffice.

It’s an inconsequential difference for most purposes, but apparently it bugs him, so he fixed it… although he went on to observe that he hadn’t managed to successfully tackle all the instances in which WordPress was outputting redundant closing marks.

This is a problem that I’ve already solved here on my blog. My solution’s slightly hacky… but it works!

/>s” isn’t among them.

My Solution: Runing HTMLTidy over WordPress

Tidy is an excellent tool for tiding up HTML! I used to use its predecessor back in the day for all kind of things, but it languished for a few years and struggled with support for modern HTML features. But in 2015 it made a comeback and it’s gone from strength to strength ever since.

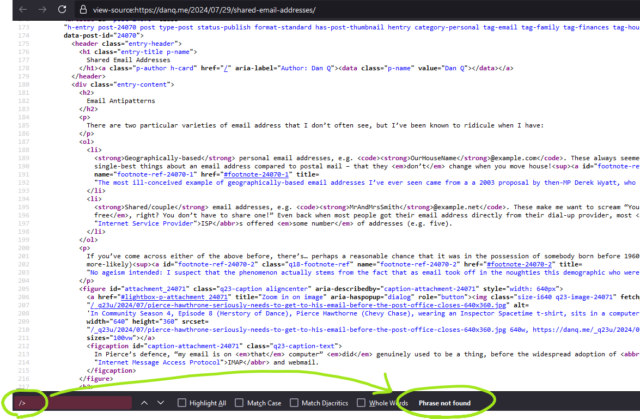

I run it on virtually all pages produced by DanQ.me (go on, click “View Source” and see for yourself!), to:

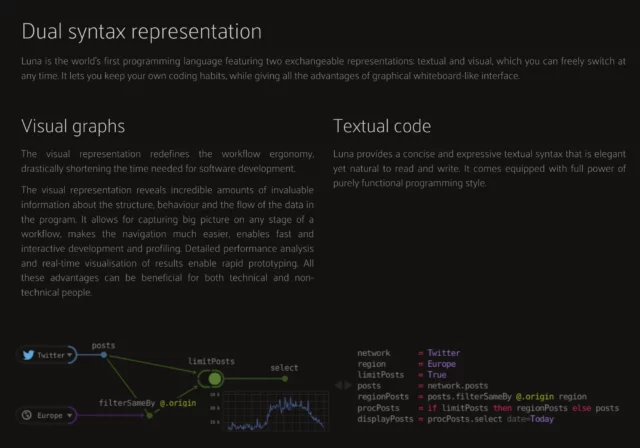

- Standardise the style of the HTML code and make it easier for humans to read1.

- Bring old-style emphasis tags like

<i>, in my older posts, into a more-modern interpretation, like<em>. - Hoist any inline

<style>blocks to the<head>, and detect any repeated inlinestyle="..."s to convert to classes. - Repair any invalid HTML (browsers do this for you, of course, but doing it server-side makes parsing easier for the browser, which might matter on more-lightweight hardware).

WordPress isn’t really designed to have Tidy bolted onto it, so anything it likely to be a bit of a hack, but here’s my approach:

-

Install

libtidy-devand build the PHP bindings to it.

Note that if you don’t do this the code might appear to work, but it won’t actually tidy anything2. -

Add a new output buffer to my theme’s

header.php3, with a callback function:ob_start('tidy_entire_page').

Without an correspondingob_flushor similar, this buffer will close and the function will be called when PHP finishes generating the page. -

Define the

function tidy_entire_page($buffer)

Have it instantiate Tidy ($tidy = new tidy) and use$tidy->parseString(with your buffer and Tidy preferences) to tidy the code, thenreturn $tidy. -

Ensure that you’re caching the results!

You don’t want to run this every page load for anonymous users! WP Super Cache on “Expert” mode (with the requisite webserver configuration) might help.

I’ve open-sourced a demonstration that implements a child theme to TwentyTwentyOne to do this: there’s a richer set of instructions in the repo’s readme. If you want, you can run my example in Docker and see for yourself how it works before you commit to trying to integrate it into your own WordPress installation!

Footnotes

1 I miss the days when most websites were handwritten and View Source typically looked nice. It was great to learn from, too, especially in an age before we had DOM debuggers. Today: I can’t justify dropping my use of a CMS, but I can make my code readable.

2 For a few of its extensions, some PHP developer made the interesting choice to fail silently if the required extension is missing. For example: if you don’t have the

zip extension enabled you can still use PHP to make ZIP files, but they won’t be

compressed. This can cause a great deal of confusion for developers! A similar issue exists with tidy: if it isn’t installed, you can still call all of the

methods on it… they just don’t do anything. I can see why this decision might have been made – to make the language as portable as possible in production – but I’d

prefer if this were an optional feature, e.g. you had to set try_to_make_do_if_you_are_missing_an_extension=yes in your php.ini to enable it, or if

it at least logged that it had done so.

3 My approach probably isn’t suitable for FSE (“block”) themes, sorry.