If you’ve been a programmer or programming-adjacent nerd1 for a while, you’ll have doubtless come across an ASCII table.

An ASCII table is useful. But did you know it’s also beautiful and elegant.

History

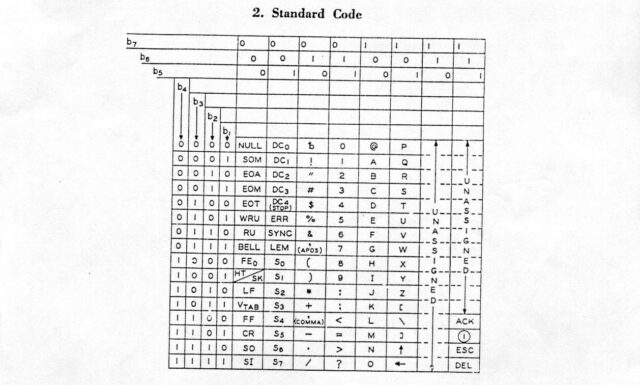

ASCII was initially standardised in X3.4-1963 (which just rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?) which assigned meanings to 100 of the potential 128 codepoints presented by a 7-bit4 binary representation: that is, binary values 0000000 through 1111111:

If you’ve already guessed where I’m going with this, you might be interested to look at the X3.4-1963 table and see that yes, many of the same elegant design choices I’ll be talking about later already existed back in 1963. That’s really cool!

Table

In case you’re not yet intimately familiar with it, let’s take a look at an ASCII table. I’ve colour-coded some of the bits I think are most-beautiful:

That table only shows decimal and

hexadecimal values for each character, but we’re going to need some binary too, to really appreciate some of the things that make ASCII sublime and clever.

Control codes

The first 32 “characters” (and, arguably, the final one) aren’t things that you can see, but commands sent between machines to provide additional instructions. You might be

familiar with carriage return (0D) and line feed (0A) which mean “go back to the beginning of this line” and “advance to the next line”,

respectively5.

Many of the others don’t see widespread use any more – they were designed for very different kinds of computer systems than we routinely use today – but they’re all still there.

32 is a power of two, which means that you’d rightly expect these control codes to mathematically share a particular “pattern” in their binary representation with one another, distinct

from the rest of the table. And they do! All of the control codes follow the pattern 00_____: that is, they begin with two zeroes. So when you’re reading

7-bit ASCII6, if it starts with

00, it’s a non-printing character. Otherwise it’s a printing character.

Not only does this pattern make it easy for humans to read (and, with it, makes the code less-arbitrary and more-beautiful); it also helps if you’re an ancient slow computer system comparing one bit of information at a time. In this case, you can use a decision tree to make shortcuts.

1111111. This

is a historical throwback to paper tape, where the keyboard would punch some permutation of seven holes to represent the ones and zeros of each character. You can’t delete

holes once they’ve been punched, so the only way to mark a character as invalid was to rewind the tape and punch out all the holes in that position: i.e. all

1s.

Space

The first printing character is space; it’s an invisible character, but it’s still one that has meaning to humans, so it’s not a control character (this sounds obvious today, but it was actually the source of some semantic argument when the ASCII standard was first being discussed).

Putting it numerically before any other printing character was a very carefully-considered and deliberate choice. The reason: sorting. For a computer to sort a list (of files, strings, or whatever) it’s easiest if it can do so numerically, using the same character conversion table as it uses for all other purposes7. The space character must naturally come before other characters, or else John Smith won’t appear before Johnny Five in a computer-sorted list as you’d expect him to.

Being the first printing character, space also enjoys a beautiful and memorable binary representation that a human can easily recognise: 0100000.

Numbers

The position of the Arabic numbers 0-9 is no coincidence, either. Their position means that they start with zero at the nice round binary value 0110000

(and similarly round hex value 30) and continue sequentially, giving:

| Binary | Hex | Decimal digit (character) |

|---|---|---|

011 0000

|

30

|

0 |

011 0001

|

31

|

1 |

011 0010

|

32

|

2 |

011 0011

|

33

|

3 |

011 0100

|

34

|

4 |

011 0101

|

35

|

5 |

011 0110

|

36

|

6 |

011 0111

|

37

|

7 |

011 1000

|

38

|

8 |

011 1001

|

39

|

9 |

The last four digits of the binary are a representation of the value of the decimal digit depicted. And the last digit of the hexadecimal representation is the decimal digit. That’s just brilliant!

If you’re using this post as a way to teach yourself to “read” binary-formatted ASCII in your head,

the rule to take away here is: if it begins 011, treat the remainder as a binary representation of an actual number. You’ll probably be

right: if the number you get is above 9, it’s probably some kind of punctuation instead.

Shifted Numbers

Subtract 0010000 from each of the numbers and you get the shifted numbers. The first one’s occupied by the space character already, which is a

shame, but for the rest of them, the characters are what you get if you press the shift key and that number key at the same time.

“No it’s not!” I hear you cry. Okay, you’re probably right. I’m using a 105-key ISO/UK QWERTY keyboard and… only four of the nine digits 1-9 have their shifted variants properly represented in ASCII.

That, I’m afraid, is because ASCII was based not on modern computer keyboards but on the shifted positions of a Remington No. 2 mechanical typewriter – whose shifted layout was the closest compromise we could find as a standard at the time, I imagine. But hey, you got to learn something about typewriters today, if that’s any consolation.

Letters

Like the numbers, the letters get a pattern. After the @-symbol at 1000000, the uppercase letters all begin

10, followed by the binary representation of their position in the alphabet. 1 = A = 1000001, 2 = B = 1000010, and so on up to 26 = Z =

1011010. If you can learn the numbers of the positions of the letters in the alphabet, and you can count

in binary, you now know enough to be able to read any ASCII uppercase letter that’s been encoded as

binary8.

And once you know the uppercase letters, the lowercase ones are easy too. Their position in the table means that they’re all exactly 0100000

higher than the uppercase variants; i.e. all the lowercase letters begin 11! 1 = a = 1100001, 2 = b = 1100010, and 26 = z =

1111010.

If you’re wondering why the uppercase letters come first, the answer again is sorting: also the fact that the first implementation of ASCII, which we saw above, was put together before it was certain that computer systems would need separate character codes for upper and lowercase letters (you could conceive of an alternative implementation that instead sent control codes to instruct the recipient to switch case, for example). Given the ways in which the technology is now used, I’m glad they eventually made the decision they did.

Beauty

There’s a strange and subtle charm to ASCII. Given that we all use it (or things derived from it) literally all the time in our modern lives and our everyday devices, it’s easy to think of it as just some arbitrary encoding.

But the choices made in deciding what streams of ones and zeroes would represent which characters expose a refined logic. It’s aesthetically pleasing, and littered with historical artefacts that teach us a hidden history of computing. And it’s built atop patterns that are sufficiently sophisticated to facilitate powerful processing while being coherent enough for a human to memorise, learn, and understand.

Footnotes

1 Programming-adjacent? Yeah. For example, geocachers who’ve ever had to decode a puzzle-geocache where the coordinates were presented in binary (by which I mean: a binary representation of ASCII) are “programming-adjacent nerds” for the purposes of this discussion.

2 In both the book and the film, Mark Watney divides a circle around the recovered Pathfinder lander into segments corresponding to hexadecimal digits 0 through F to allow the rotation of its camera (by operators on Earth) to transmit pairs of 4-bit words. Two 4-bit words makes an 8-bit byte that he can decode as ASCII, thereby effecting a means to re-establish communication with Earth.

3 Y’know, so that you can type all those emoji you love so much.

4 ASCII is often thought of as an 8-bit code, but it’s not: it’s 7-bit. That’s why virtually every ASCII message you see starts every octet with a zero. 8-bits is a convenient number for transmission purposes (thanks mostly to being a power of two), but early 8-bit systems would be far more-likely to use the 8th bit as a parity check, to help detect transmission errors. Of course, there’s also nothing to say you can’t just transmit a stream of 7-bit characters back to back!

5 Back when data was sent to teletype printers these two characters had a distinct

different meaning, and sometimes they were so slow at returning their heads to the left-hand-side of the paper that you’d also need to send a few null bytes e.g. 0D 0A

00 00 00 00 to make sure that the print head had gotten settled into the right place before you sent more data: printers didn’t have memory buffers at this point! For

compatibility with teletypes, early minicomputers followed the same carriage return plus line feed convention, even when outputting text to screens. Then to maintain backwards

compatibility with those systems, the next generation of computers would also use both a carriage return and a line feed character to mean “next line”. And so,

in the modern day, many computer systems (including Windows most of the time, and many Internet protocols) still continue to use the combination of a carriage return

and a line feed character every time they want to say “next line”; a redundancy build for a chain of backwards-compatibility that ceased to be relevant decades ago but which

remains with us forever as part of our digital heritage.

6 Got 8 binary digits in front of you? The first digit is probably zero. Drop it. Now you’ve got 7-bit ASCII. Sorted.

7 I’m hugely grateful to section 13.8 of Coded Character Sets, History and Development by Charles E. Mackenzie (1980), the entire text of which is available freely online, for helping me to understand the importance of the position of the space character within the ASCII character set. While most of what I’ve written in this blog post were things I already knew, I’d never fully grasped its significance of the space character’s location until today!

8 I’m sure you know this already, but in case you’re one of today’s lucky 10,000 to discover that the reason we call the majuscule and minuscule letters “uppercase” and “lowercase”, respectively, dates to 19th century printing, when moveable type would be stored in a box (a “type case”) corresponding to its character type. The “upper” case was where the capital letters would typically be stored.

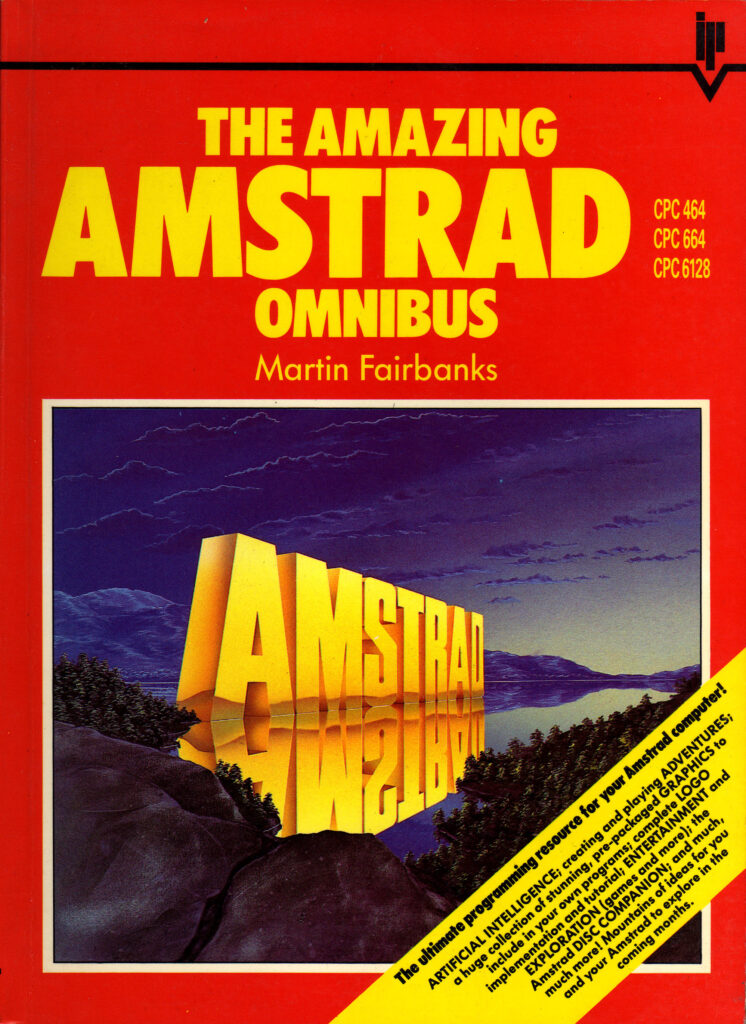

![Scan of a ring-bound page from a technical manual. The page describes the use of the "INPUT" command, saying "This command is used to let the computer know that it is expecting something to be typed in, for example, the answer to a question". The page goes on to provide a code example of a program which requests the user's age and then says "you look younger than [age] years old.", substituting in their age. The page then explains how it was the use of a variable that allowed this transaction to occur.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2023/07/cpc664-manual-input-command.png)