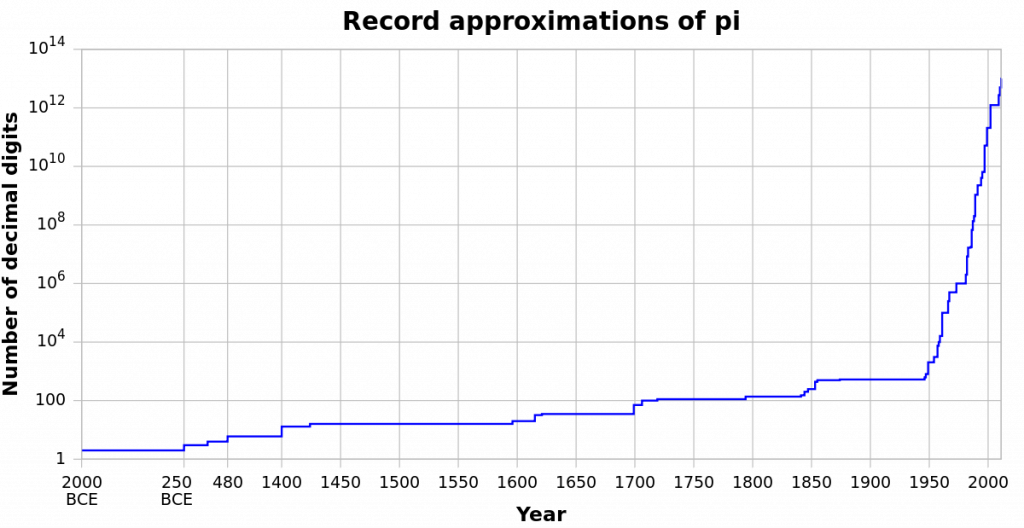

If you’ve spent any time thinking about complex systems, you surely understand the importance of networks.Networks rule our world. From the chemical reaction pathways inside a cell, to the web of relationships in an ecosystem, to the trade and political networks that shape the course of history.Or consider this very post you’re reading. You probably found it on a social network, downloaded it from a computer network, and are currently deciphering it with your neural network.But as much as I’ve thought about networks over the years, I didn’t appreciate (until very recently) the importance of simple diffusion.This is our topic for today: the way things move and spread, somewhat chaotically, across a network. Some examples to whet the appetite:

- Infectious diseases jumping from host to host within a population

- Memes spreading across a follower graph on social media

- A wildfire breaking out across a landscape

- Ideas and practices diffusing through a culture

- Neutrons cascading through a hunk of enriched uranium

A quick note about form.Unlike all my previous work, this essay is interactive. There will be sliders to pull, buttons to push, and things that dance around on the screen. I’m pretty excited about this, and I hope you are too.So let’s get to it. Our first order of business is to develop a visual vocabulary for diffusion across networks.A simple model

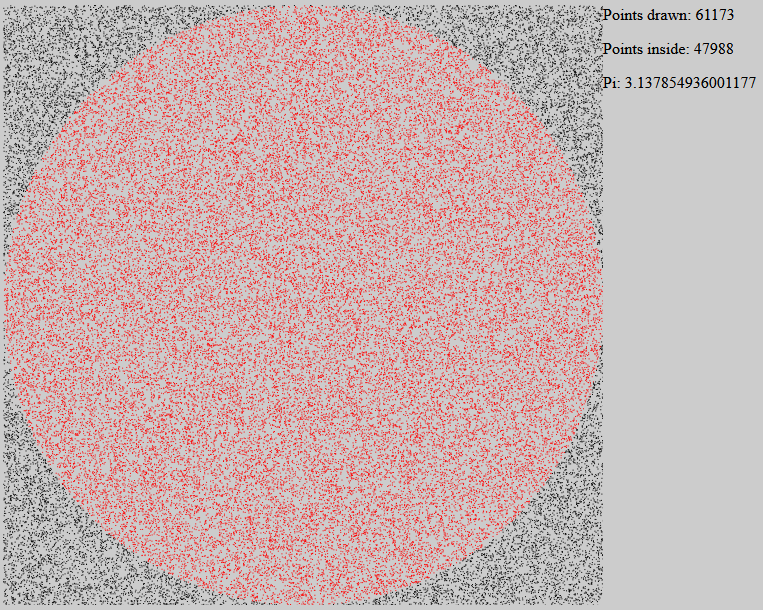

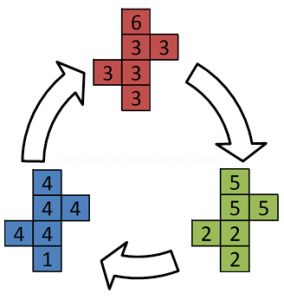

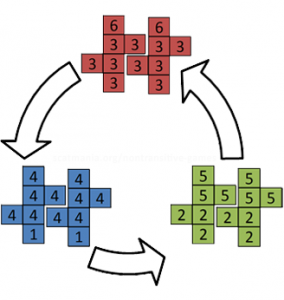

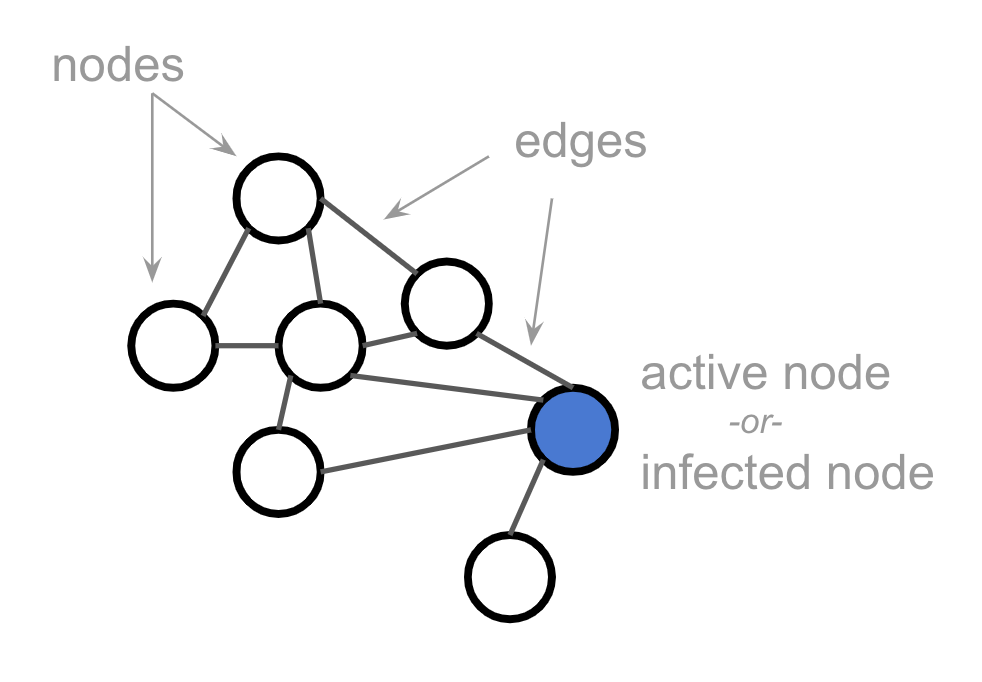

I’m sure you all know the basics of a network, i.e., nodes + edges.To study diffusion, the only thing we need to add is labeling certain nodes as active. Or, as the epidemiologists like to say, infected: This activation or infection is what will be diffusing across the network. It spreads from node to node according to rules we’ll develop below.Now, real-world networks are typically far bigger than this simple 7-node network. They’re also far messier. But in order to simplify — we’re building a toy model here — we’re going to look at grid or lattice networks throughout this post.(What a grid lacks in realism, it makes up for in being easy to draw ;)Except where otherwise specified, the nodes in our grid will have 4 neighbors, like so:And we should imagine that these grids extend out infinitely in all directions. In other words, we’re not interested in behavior that happens only at the edges of the network, or as a result of small populations.Given that grid networks are so regular, we can simplify by drawing them as pixel grids. These two images represent the same network, for example:

This activation or infection is what will be diffusing across the network. It spreads from node to node according to rules we’ll develop below.Now, real-world networks are typically far bigger than this simple 7-node network. They’re also far messier. But in order to simplify — we’re building a toy model here — we’re going to look at grid or lattice networks throughout this post.(What a grid lacks in realism, it makes up for in being easy to draw ;)Except where otherwise specified, the nodes in our grid will have 4 neighbors, like so:And we should imagine that these grids extend out infinitely in all directions. In other words, we’re not interested in behavior that happens only at the edges of the network, or as a result of small populations.Given that grid networks are so regular, we can simplify by drawing them as pixel grids. These two images represent the same network, for example: Alright, let’s get interactive.…

Alright, let’s get interactive.…

Fabulous (interactive! – click through for the full thing to see for yourself) exploration of network interactions with applications for understanding epidemics, memes, science, fashion, and much more. Plus Kevin’s made the whole thing CC0 so everybody can share and make use of his work. Treat as a longread with some opportunities to play as you go along.