The phone rings. It’s clear to me by the sound it makes and by the image on it’s display that this is a business call.

“Good morning, SmartData; Dan speaking,” I say.

The caller identifies themselves, and asks to speak to Alex, another SmartData employee. I look to my right to see if Alex is available

(presumably if he was, he’d have answered the call before it had been forwarded to me). This is possible because of the two-way webcam feed on the monitor beside me.

“I’m afraid Alex isn’t in yet,” I begin, bringing up my co-worker’s schedule on the screen in front of me, to determine what he’s up to, “He’ll be in at about 10:30 this

morning. Can I get him to call you back?”

Not for a second did it occur to the caller that I wasn’t sat right there in the office, looking over at Alex’s chair and a physical calendar. Of course, I’m actually hundreds of miles

away, in my study in Oxford. Most of our clients – even those whom I deal with directly – don’t know that I’m no longer based out of SmartData’s marina-side offices. Why would they need

to? Just about everything I can do from the office I can do from my own home. Aside from sorting the mail on a morning and taking part in the occasional fire drill, everything I’d

regularly do from Aberystwyth I can do from here.

Back when I was young, I remember reading a book once which talked about advances in technology and had wonderful pictures of what life would be like in the future. This wasn’t a

dreamland of silver jumpsuits and jetpacks; everything they talked about in this book was rooted in the trends that we were already beginning to see. Published in the early 80s, it

predicted a microcomputer in every home and portable communicators that everybody would have that could be used to send messages or talk to anybody else, all before the 21st century.

Give or take, that’s all come to pass. I forget what the title of the book was, but I remember enjoying it as a child because it seemed so believable, so real. I guess it inspired a

hopeful futurism in me.

But it also made another prediction: that with this rise in telecommunications technologies and modern microcomputers (remember when we still routinely called them that?), we’d see a

greap leap in the scope for teleworking: office workers no longer going to a place

of work, but remotely “dialling in” to a server farm in a distant telecentre. Later, it predicted, with advances in robotics, specialist workers like surgeons would be able to operate

remotely too: eventually, through mechanisation of factories, even manual labourers would begun to be replaced by work-at-home operators sat behind dumb terminals.

To play on a cliché: where’s my damn flying car?

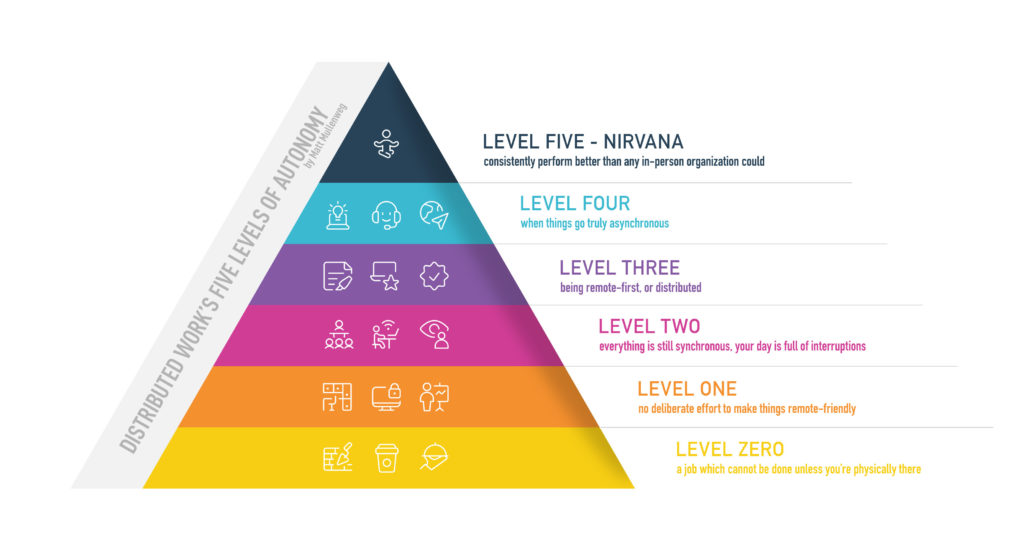

By now, I thought that about a quarter of us would be working from home full-time or most of the time, with many more – especially in my field, where technology comes naturally –

working from home occasionally. Instead, what have we got? Somewhere in the region of one in fifty, and that includes the idiots who’ve fallen for the “Make £££ working from home” scams

that do the rounds every once in a while and haven’t yet realised that they’re not going to make any £, let alone £££.

At first, I thought that this was due to all of the traditionally-cited reasons: companies that don’t trust their employees, managers who can’t think about results-based assessment

rather than presence-based assessment, old-school thinking, and not wanting to be accused of favouritism by allowing some parts of their work force to telework while others can’t. In

some parts of the world, and some fields, we’ve actually seen a decrease in teleworking over recent years: what’s all that about?

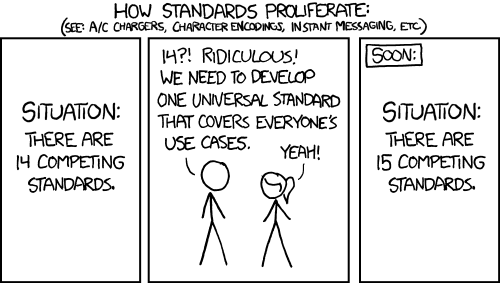

I’m sure that the concerns listed above are still critical factors for many companies, but I’ve realised that there could be another, more-recent fear that’s now preventing the uptake

of teleworking in many companies. That fear is one that affects everybody – both the teleworkers and their comrades in the offices, and it’s something that more and more managers are

becoming aware of: the fear of outsourcing.

After all, if a company’s employees can do their work from home, then they can do it from anywhere. With a little extra work on technical infrastructure and a liberal attitude

to meetings, the managers can work from anywhere, too. So why stop at working from home? Once you’ve demonstrated that your area of work can be done without coming in to the office,

then you’re half-way to demonstrating that it can be done from Mumbai or Chennai, for a fraction of the price… and that’s something that’s a growing fear for many kinds of technical

workers in the Western world.

Our offices are a security blanket: we’re clinging on to them because we like to pretend that they’ll protect us; that they’re something special and magical that we can offer our

clients that the “New World” call centres and software houses in India and China can’t offer them. I’m not sure that a security blanket that allows us to say “we have a local presence”

will mean as much in ten years time as it does today.

In the meantime, I’m still enjoying working from home. It’s a little lonely, sometimes – on days when JTA isn’t

around, which are going to become more common when he starts his new job – but the instant messenger and Internet telephony tools we use make it feel a little like I’m

actually in the office, and that’s a pretty good trade-off in exchange for being able to turn up at work in my underwear, if I like.