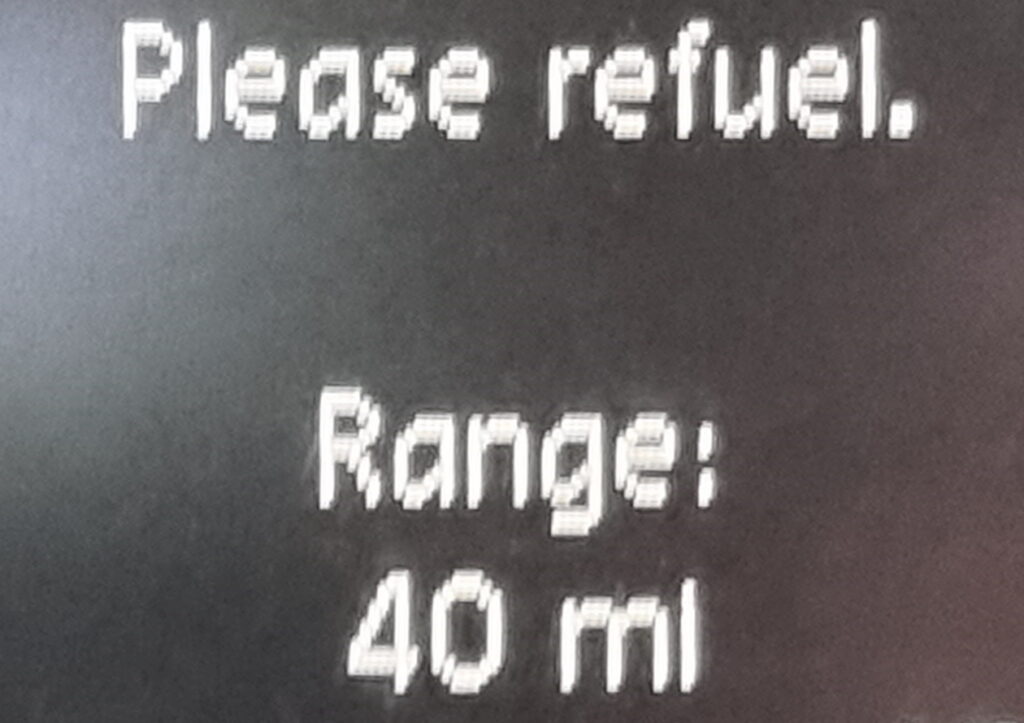

Tonight I learned that when my electric car gets down to 5% battery, it sounds an alarm.

And that when it gets down to 4% battery, it sounds a louder alarm.

And that when it gets down to 3% battery, it engages ‘limited performance’ mode and shows a picture of a tortoise.

And that when it gets down to 2%, and you’ve already turned off the heating and the radio and you’re wondering how much power the windscreen wipers are using… that’s when it stops

showing you it’s estimated range.

Fortunately, I then only had half a mile left to go. But for a while there it felt a little bit hairy!

Tag: cars

Heterophonic Homonyms

The elder of our two cars is starting to exhibit a few minor, but annoying, technical faults. Like: sometimes the Bluetooth connection to your phone will break and instead of music, you just get a non-stop high-pitched screaming sound which you can suppress by turning off the entertainment system… but can’t fix without completely rebooting the entire car.

The “wouldn’t you rather listen to screaming” problem occurred this morning. At the time, I was driving the kids to an activity camp, and because they’d been quite enjoying singing along to a bangin’ playlist I’d set up, they pivoted into their next-most-favourite car journey activity of trying to snipe at one another1. So I needed a distraction. I asked:

We’ve talked about homonyms and homophones before, haven’t we? I wonder: can anybody think of a pair of words that are homonyms that are not homophones? So: two words that are spelled the same, but mean different things and sound different when you say them?

This was sufficiently distracting that it not only kept the kids from fighting for the entire remainder of the journey, but it also distracted me enough that I missed the penultimate turning of our journey and had to double-back2

…in English

With a little prompting and hints, each of the kids came up with one pair each, both of which exploit the pronunciation ambiguity of English’s “ea” phoneme:

-

Lead, as in:

- /lɛd/ The pipes are made of lead.

- /liːd/ Take the dog by her lead.

-

Read, as in:

- /ɹɛd/ I read a great book last month.

- /ɹiːd/ I will read it after you finish.

These are heterophonic homonyms: words that sound different and mean different things, but are spelled the same way. The kids and I only came up with the two on our car journey, but I found many more later in the day. Especially, as you might see from the phonetic patterns in this list, once I started thinking about which other sounds are ambiguous when written:

- Tear (/tɛr/ | /tɪr/): she tears off some paper to wipe her tears away.

- Wind (/waɪnd/ | /wɪnd/): don’t forget to wind your watch before you wind your horn.

- Live (/laɪv/ | /lɪv/): I’d like to see that band live if only I could live near where they play.

- Bass (/beɪs/ | /bæs/): I play my bass for the bass in the lake.

- Bow (/baʊ/ | /boʊ/): take a bow before you notch an arrow into your bow.

- Sow (/saʊ/ | /soʊ/): the pig and sow ate the seeds as fast as I could sow them.

- Does (/dʌz/ | /doʊz/): does she know about the bucks and does in the forest?

(If you’ve got more of these, I’d love to hear read them!)

…in other Languages?

I’m interested in whether heterophonic homonyms are common in any other languages than English? English has a profound advantage for this kind of wordplay3, because it has weakly phonetics (its orthography is irregular: things aren’t often spelled like they’re said) and because it has diverse linguistic roots (bits of Latin, bits of Greek, some Romance languages, some Germanic languages, and a smattering of Celtic and Nordic languages).

With a little exploration I was able to find only two examples in other languages, but I’d love to find more if you know of any. Here are the two I know of already:

- In French I found couvent, which works only thanks to a very old-fashioned word:

- /ku.vɑ̃/ means convent, as in – where you keep your nuns, and

- /ku.və/ means sit on, but specifically in the manner that a bird does on its egg, although apparently this usage is considered archaic and the word couver is now preferred.

- In Portugese I cound pelo, which works only because modern dialects of Portugese have simplified or removed the diacritics that used to differentiate the

spellings of some words:

- /ˈpe.lu/ means hair, like that which grows on your head, and

- /ˈpɛ.lu/ means to peel, as you would with an orange.

If you speak more or different languages than me and can find others for me to add to my collection of words that are spelled the same but that are pronounced differently, I’d love to hear them.

Special Bonus Internet Points for anybody who can find such a word that can reasonably be translated into another language as a word which also exhibits the same phenomenon. A pun that can only be fully understood and enjoyed by bilingual speakers would be an especially exciting thing to behold!

Footnotes

1 I guess close siblings are just gonna go through phases where they fight a lot, right? But if you’d like to reassure me that for most it’s just a phase and it’ll pass, that’d be nice.

2 In my defence, I was navigating from memory because my satnav was on my phone and it was still trying to talk over Bluetooth to the car… which was turning all of its directions into a high-pitched scream.

3 If by “advantage” you mean “is incredibly difficult for non-native speakers to ever learn fluently”.

Waves Hand Car Wash

Note #26625

To-go pint

Note #25552

Note #25538

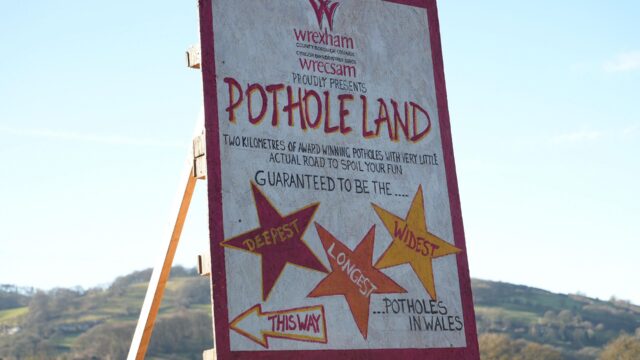

This is funny, but I’m confident Wrexham’s potholes have nothing on the Trinbagonian ones I’ve been experiencing all week, which have sometimes spanned most of the width of a road or been deep enough that dipping a wheel into them would strike the road with your underchassis!

Irish Signs

I’ve only been driving in Ireland for several days, so less than 100% of the iconography of the signage makes sense to me instantly, for now. But this one’s a complete mystery to me.

Is this warning joggers than tiny cars might bounce off their heads? Or is it exhorting distant swerving motorists to put on their right indicator to tell people which way to run to avoid being hit by them? Or maybe it’s advising that down this road is a football pitch for giants and they’ll play “headers” with you in your car if you’re not careful? I honestly haven’t a clue.

My Car is Sad

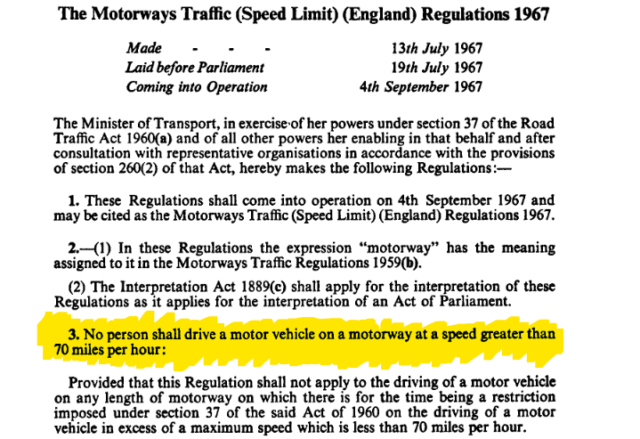

Special Roads

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Sometimes I’ve seen signs on dual carriageways and motorways that seem to specify a speed limit that’s the same as the national speed limit (i.e. 60 or 70 mph for most vehicles, depending on the type of road), which seem a bit… pointless? Today I learned why they’re there, and figured I’d share with you!

To get there, we need a history lesson.

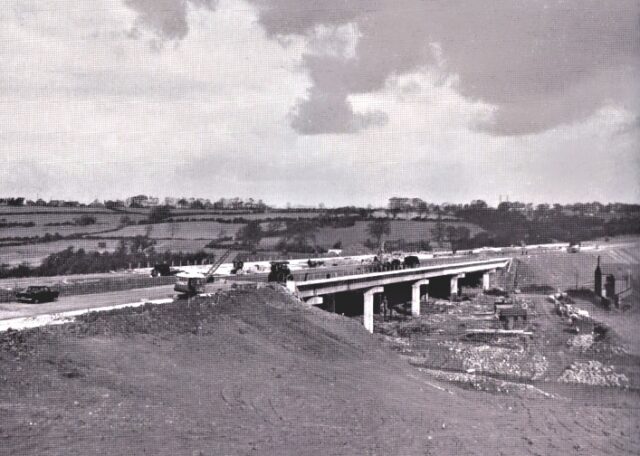

As early as the 1930s, it was becoming clear that Britain might one day need a network of high-speed, motor-vehicle-only roads: motorways. The first experimental part of this network would be the Preston By-pass1.

Construction wouldn’t actually begin until the 1950s, and it wasn’t just the Second World War that got in the way: there was a legislative challenge too.

When the Preston By-pass was first conceived, there was no legal recognition for roads that restricted the types of traffic that were permitted to drive on them. If a public highway were built, it would have to allow pedestrians, cyclists, and equestrians, which would doubtless undermine the point of the exercise! Before it could be built, the government needed to pass the Special Roads Act 1949, which enabled the designation of public roads as “special roads”, to which entry could be limited to certain classes of vehicles2.

If you don’t check your sources carefully when you research the history of special roads, you might be taken in by articles that state that special roads are “now known as motorways”, which isn’t quite true. All motorways are special roads, by definition, but not all special roads are motorways.

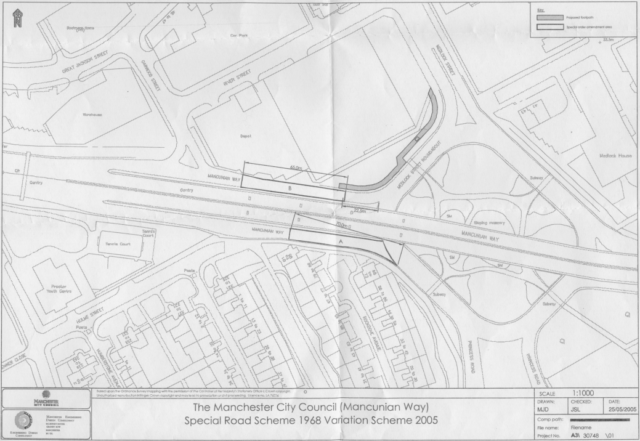

There’s maybe a dozen or more non-motorway special roads, based on research by Pathetic Motorways (whose site was amazingly informative on this entire subject). They tend to be used in places where something is like a motorway, but can’t quite be a motorway. In Manchester, a couple of the A57(M)’s sliproads have pedestrian crossings and so have to be designated special roads rather than motorways, for example3.

Now we know what special roads are, that we might find them all over the place, and that they can superficially look like motorways, let’s talk about speed limits.

The Road Traffic Act 1934 introduced the concept of a 30mph “national speed limit” in built-up areas, which is still in force today. But outside of urban areas there was no speed limit. Perhaps there didn’t need to be, while cars were still relatively slow, but automobiles became increasingly powerful. The fastest speed ever legally achieved on a British motorway came in 1964 during a test by AC Cars, when driver Jack Sears reached 185mph.

In the late 1960s an experiment was run in setting a speed limit on motorways of 70mph. Then the experiment was extended. Then the regulation was made permanent.

There’ve been changes since then, e.g. to prohibit HGVs from going faster than 60mph, but fundamentally this is where Britain’s national speed limit on motorways comes from.

You’ve probably spotted the quirk already. When “special roads” were created, they didn’t have a speed limit. Some “special roads” were categorised as “motorways”, and “motorways” later had a speed limit imposed. But there are still a few non-motorway “special roads”!

Putting a national speed limit sign on a special road would be meaningless, because these roads have no centrally-legislated speed limit. So they need a speed limit sign, even if that sign, confusingly, might specify a speed limit that matches what you’d have expected on such a road4. That’s the (usual) reason why you sometimes see these surprising signs.

As to why this kind of road are much more-common in Scotland and Wales than they are anywhere else in the UK: that’s a much deeper-dive that I’ll leave as an exercise for the reader.

Footnotes

1 The Preston By-pass lives on, broadly speaking, as the M6 junctions 29 through 32.

2 There’s little to stop a local authority using the powers of the Special Roads Act and its successors to declare a special road accessible to some strange and exotic permutation of vehicle classes if they really wanted: e.g. a road could be designated for cyclists and horses but forbidden to motor vehicles and pedestrians, for example! (I’m moderately confident this has never happened.)

3 There’s a statutory instrument that makes those Mancunian sliproads possible, if you’re having trouble getting to sleep on a night and need some incredibly dry reading.

4 An interesting side-effect of these roads might be that speed restrictions based on the class of your vehicle and the type of road, e.g. 60mph for lorries on motorways, might not be enforceable on special roads. If you wanna try driving your lorry at 70mph on a motorway-like special road with “70” signs, though, you should do your own research first; don’t rely on some idiot from the Internet. I Am Not A Lawyer etc. etc.

Mathematics of Mid-Journey Refuelling

I love my electric car, but sometimes – like when I need to transport five people and a week’s worth of their luggage 250 miles and need to get there before the kids’ bedtime! – I still use our big ol’ diesel-burning beast. And it was while preparing for such a journey that I recently got to thinking about the mathematics of refuelling.

It’s rarely worth travelling out-of-your-way to get the best fuel prices. But when you’re on a long road trip anyway and you’re likely to pass dozens of filling stations as a matter of course, you might as well think at least a little about pulling over at the cheapest.

You could use one of the many online services to help with this, of course… but assuming you didn’t do this and you’re already on the road, is there a better strategy than just trusting your gut and saying “that’s good value!” when you see a good price?

It turns out this is an application for the Secretary Problem (and probably a little more sensible than the last time I talked about it!).

Here’s how you do it:

- Estimate your outstanding range R: how much further can you go? Your car might be able to help you with this. Let’s say we’ve got 82 miles in the tank.

- Estimate the average distance between filling stations on your route, D. You can do this as-you-go by counting them over a fixed distance and continue from step #4 as you do so, and it’ll only really mess you up if there are very few. Maybe we’re on a big trunk road and there’s a filling station about every 5 miles.

- Divide R by D to get F: the number of filling stations you expect to pass before you completely run out of fuel. Round down, obviously, unless you’re happy to push your vehicle to the “next” one when it breaks down. In our example above, that gives us 16 filling stations we’ll probably see before we’re stranded.

- Divide F by e to get T (use e = 2.72 if you’re having to do this in your head). Round down again, for the same reason as before. This gives us T=5.

- Drive past the next T filling stations and remember the lowest price you see. Don’t stop for fuel at any of these.

- Keep driving, and stop at the first filling station where the fuel is the same price or cheaper than the cheapest you’ve seen so far.

This is a modified variant of the Secretary Problem because it’s possible for two filling stations to have the same price, and that’s reflected in the algorithm above by the allowance for stopping for fuel at the same price as the best you saw during your sampling phase. It’s probably preferable to purchase sub-optimally than to run completely dry, right?

Of course, you’re still never guaranteed a good solution with this approach, but it maximises your odds. Your own risk-assessment might rank “not breaking down” over pure mathematical efficiency, and that’s on you.

Will swapping out electric car batteries catch on?

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I won’t be plugging it in though, instead, the battery will be swapped for a fresh one, at this facility in Norway belonging to Chinese electric carmaker, Nio.

The technology is already widespread in China, but the new Power Swap Station, just south of Oslo, is Europe’s first.

…

This is what I’ve been saying for years would be a better strategy for electric vehicles. Instead of charging them (the time needed to charge is their single biggest weakness compared to fuelled vehicles) we should be doing battery swaps. A decade or two ago I spoke hopefully for some kind of standardised connector and removal interface, probably below the vehicle, through which battery cells could be swapped-out by robots operating in a pit. Recovered batteries could be recharged and reconditioned by the robots at their own pace. People could still charge their cars in a plug-in manner at their homes or elsewhere.

You’d pay for the difference in charge between the old and replacement battery, plus a service charge for being part of the battery-swap network, and you’d be set. Car manufacturers could standardise on battery designs, much like the shipping industry long-ago standardised on container dimensions and whatnot, to take advantage of compatibility with the wider network.

Rather than having different sizes of battery, vehicles could be differentiated by the number of serial battery units installed. A lorry might need four or five units; a large car two; a small car one, etc. If the interface is standardised then all the robots need to be able to do is install and remove them, however many there are.

This is far from an unprecedented concept: the centuries-old idea of stagecoaches (and, later, mail coaches) used the same idea, but with the horses being changed at coaching inns rather. Did you know that the “stage” in stagecoach refers to the fact that their journey would be broken into stages by these quick stops?

Anyway: I dismayed a little when I saw every EV manufacturer come up with their own battery standards, co=operating only as far as the plug-in charging interfaces (and then, only gradually and not completely!). But I’m given fresh hope by this discovery that China’s trying to make it work, and Nio‘s movement in Norway is exciting too. Maybe we’ll get there someday.

Incidentally: here’s a great video about how AC charging works (with a US/type-1 centric focus), which briefly touches upon why battery swaps aren’t necessarily an easy problem to solve.

Honk More, Wait More

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Horn not okay, please!

Find out how the @MumbaiPolice hit the mute button on #Mumbai’s reckless honkers.

#HonkResponsibly

Indian horn culture is weird to begin with. But I just learned that apparently it’s a thing to honk your in horn in displeasure at the stationary traffic ahead of you… even when that traffic is queueing at traffic lights! In order to try to combat the cacophony, Mumbai police hooked up a decibel-meter to the traffic lights at a junction such that if the noise levels went over a certain threshold during the red light phase, the red light phase would be extended by resetting the timer.

30 Years in the making | The All-New Renault CLIO

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Last week I happened to be at an unveiling/premiere event for the new Renault Clio. That’s a coincidence: I was actually there to see the new Zoe, because we’re hoping to be among the first people to get the right-hand-drive version of the new model when it starts rolling off the production line in 2020.

But I’ll tell you what, if they’d have shown me this video instead of showing me the advertising stuff they did, last week, I’d have been all: sure thing, Clio it is, SHUT UP AND TAKE MY MONEY! I’ve watched this ad four times now and seen more things in it every single time. (I even managed to not-cry at it on the fourth watch-through, too; hurrah!).

Dan Q found GC55HCZ Take a break!!

This checkin to GC55HCZ Take a break!! reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

The battery indicator on the eV I’m renting wasn’t confident that I’d make it all the way back home without a top-up, so I stopped for a 45 minute charge and a drink – the former for the car, the latter for me – at the services (pic attached of me at the chargers: this is nowhere near the GZ!) and figured I’d try to find the cache while I was waiting.

Coords took me to an unlikely looking spot and the hint wasn’t much use, so I looked at the logs and noticed that a few people had reported that they had found themselves on the “wrong side of the road”. That could be me, too, I thought… but the wrong way… in which direction? There were two roads alongside me.

I spotted a tall white thing that was different to the others and guessed that maybe that was what the hint referred to? When I got there, I even found a likely looking hiding place, but clearly my brain is still in USA-caching mode (I was caching on California a couple of weeks ago) because the hiding place I was looking at was the kind of “LPC” that just doesn’t happen over here. Damn.

So I stopped and tried to look nonchalant for a while, pacing around and looking for anything else that might fit the clue. Then I saw three things close together on the other-other side of the road and it immediately clicked that I was looking for something like them. I crossed over, sat down on the convenient perch while I waited for some muggles to pass, retrieved the cache and – at last – signed the log in what was basically the only remaining bit of space.

Had my GPSr sent me to the right place to begin with this adventure would have been much shorter, but I got there in the end… and still with 13 minutes of charging time left before I could drive away. TFTC!