This blog post is also available as a video. Would you prefer to watch/listen to me tell you about how I’ve implemented a tool to help me beat the kids when we play Mastermind?

I swear that I used to be good at Mastermind when I was a kid. But now, when it’s my turn to break the code that one of our kids has chosen, I fail more often than I succeed. That’s no good!

Mastermind and me

Maybe it’s because I’m distracted; multitasking doesn’t help problem-solving. Or it’s because we’re “Super” Mastermind, which differs from the one I had as a child in that eight (not six) peg colours are available and secret codes are permitted to have duplicate peg colours. These changes increase the possible permutations from 360 to 4,096, but the number of guesses allowed only goes up from 8 to 10. That’s hard.

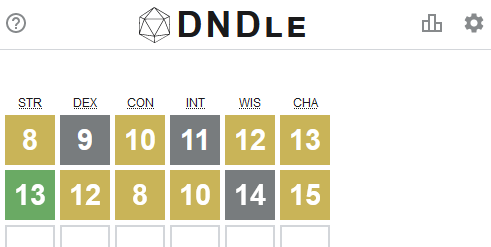

Or maybe it’s just that I’ve gotten lazy and I’m now more-likely to try to “solve” a puzzle using a computer to try to crack a code using my brain alone. See for example my efforts to determine the hardest hangman words and make an adverserial hangman game, to generate solvable puzzles for my lock puzzle game, to cheat at online jigsaws, or to balance my D&D-themed Wordle clone.

Hey, that’s an idea. Let’s crack the code… by writing some code!

Representing a search space

The search space for Super Mastermind isn’t enormous, and it lends itself to some highly-efficient computerised storage.

There are 8 different colours of peg. We can express these colours as a number between 0 and 7, in three bits of binary, like this:

| Decimal | Binary | Colour |

|---|---|---|

0

|

000

|

Red |

1

|

001

|

Orange |

2

|

010

|

Yellow |

3

|

011

|

Green |

4

|

100

|

Blue |

5

|

101

|

Pink |

6

|

110

|

Purple |

7

|

111

|

White |

There are four pegs in a row, so we can express any given combination of coloured pegs as a 12-bit binary number. E.g. 100 110 111 010 would represent the

permutation blue (100), purple (110), white (111), yellow (010). The total search space, therefore, is the range of numbers from

000000000000 through 111111111111… that is: decimal 0 through 4,095:

| Decimal | Binary | Colours |

|---|---|---|

0

|

000000000000

|

Red, red, red, red |

1

|

000000000001

|

Red, red, red, orange |

2

|

000000000010

|

Red, red, red, yellow |

| ………… | ||

4092

|

|

White, white, white, blue |

4093

|

|

White, white, white, pink |

4094

|

|

White, white, white, purple |

4095

|

|

White, white, white, white |

Whenever we make a guess, we get feedback in the form of two variables: each peg that is in the right place is a bull; each that represents a peg in the secret code but isn’t in the right place is a cow (the names come from Mastermind’s precursor, Bulls & Cows). Four bulls would be an immediate win (lucky!), any other combination of bulls and cows is still valuable information. Even a zero-score guess is valuable- potentially very valuable! – because it tells the player that none of the pegs they’ve guessed appear in the secret code.

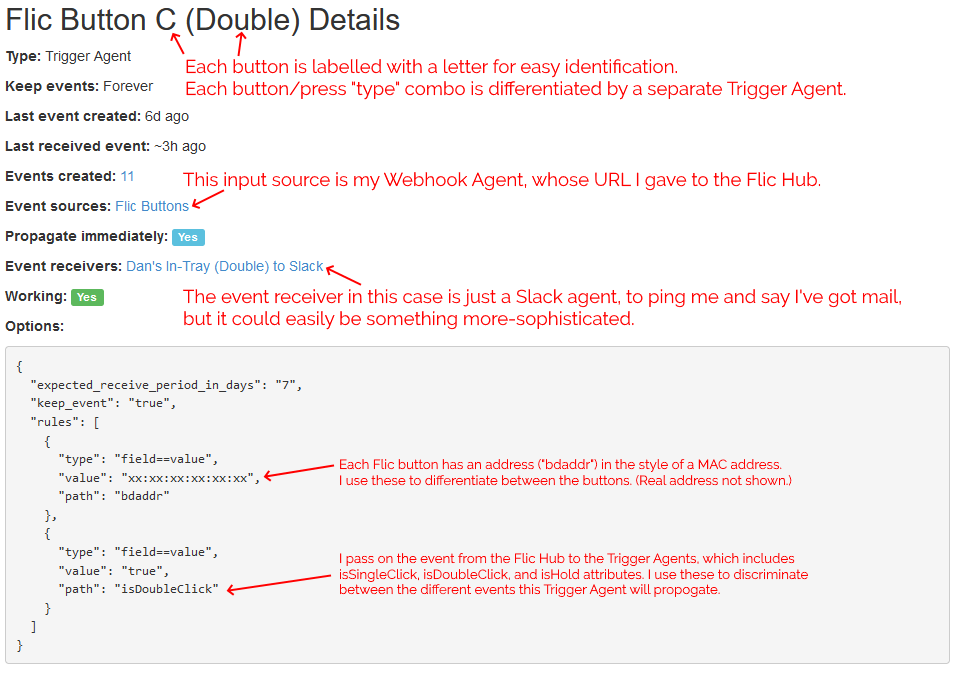

Solving with Javascript

The latest versions of Javascript support binary literals and bitwise operations, so we can encode and decode between arrays of four coloured pegs (numbers 0-7) and the number 0-4,095

representing the guess as shown below. Decoding uses an AND bitmask to filter to the requisite digits then divides by the order of magnitude. Encoding is just a reduce

function that bitshift-concatenates the numbers together.

116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 |

/** * Decode a candidate into four peg values by using binary bitwise operations. */ function decodeCandidate(candidate){ return [ (candidate & 0b111000000000) / 0b001000000000, (candidate & 0b000111000000) / 0b000001000000, (candidate & 0b000000111000) / 0b000000001000, (candidate & 0b000000000111) / 0b000000000001 ]; } /** * Given an array of four integers (0-7) to represent the pegs, in order, returns a single-number * candidate representation. */ function encodeCandidate(pegs) { return pegs.reduce((a, b)=>(a << 3) + b); } |

With this, we can simply:

- Produce a list of candidate solutions (an array containing numbers 0 through 4,095).

- Choose one candidate, use it as a guess, and ask the code-maker how it scores.

- Eliminate from the candidate solutions list all solutions that would not score the same number of bulls and cows for the guess that was made.

- Repeat from step #2 until you win.

Step 3’s the most important one there. Given a function getScore( solution, guess ) which returns an array of [ bulls, cows ] a given guess would

score if faced with a specific solution, that code would look like this (I’m convined there must be a more-performant way to eliminate candidates from the list with XOR

bitmasks, but I haven’t worked out what it is yet):

164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 |

/** * Given a guess (array of four integers from 0-7 to represent the pegs, in order) and the number * of bulls (number of pegs in the guess that are in the right place) and cows (number of pegs in the * guess that are correct but in the wrong place), eliminates from the candidates array all guesses * invalidated by this result. Return true if successful, false otherwise. */ function eliminateCandidates(guess, bulls, cows){ const newCandidatesList = data.candidates.filter(candidate=>{ const score = getScore(candidate, guess); return (score[0] == bulls) && (score[1] == cows); }); if(newCandidatesList.length == 0) { alert('That response would reduce the candidate list to zero.'); return false; } data.candidates = newCandidatesList; chooseNextGuess(); return true; } |

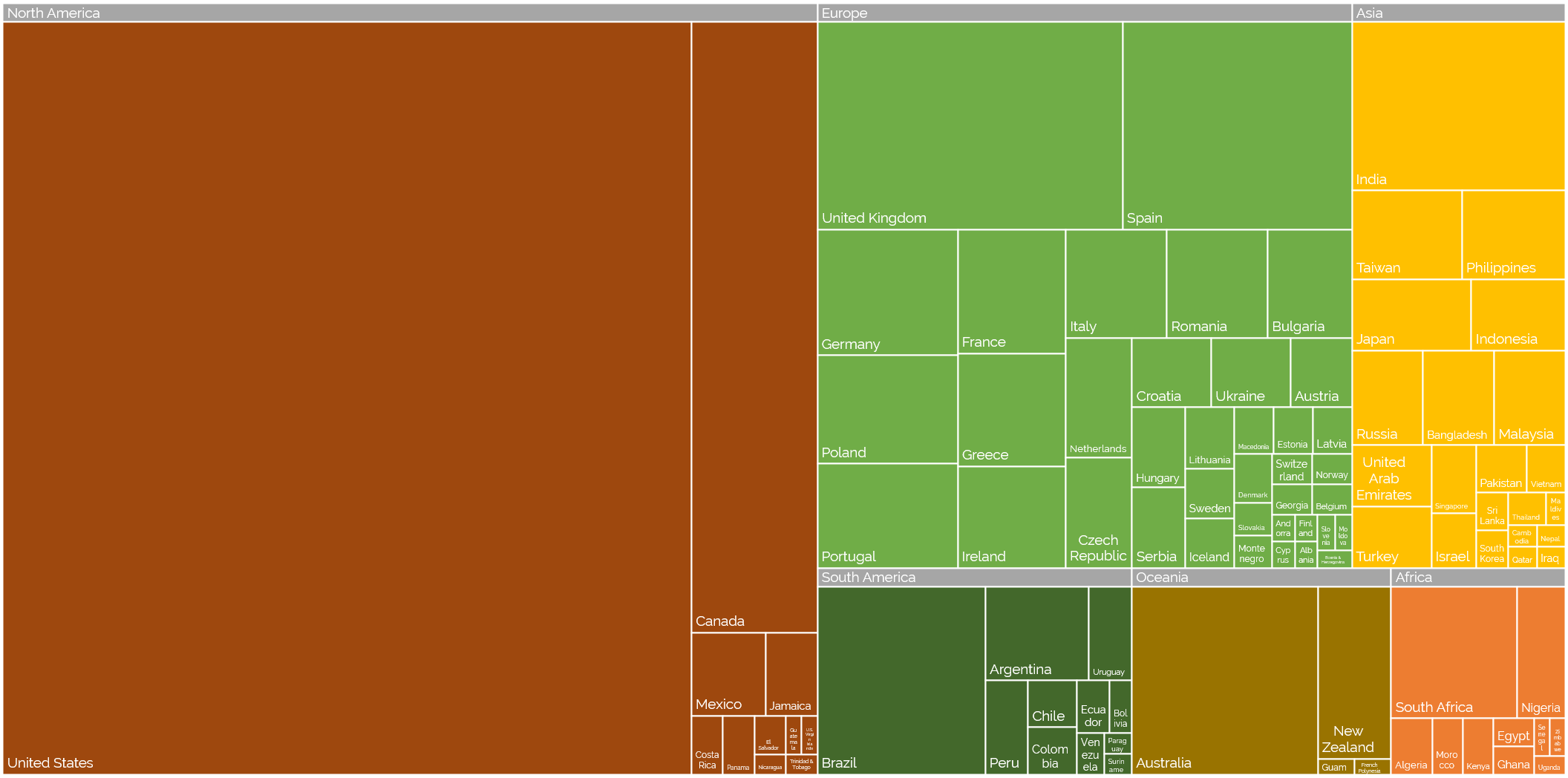

I continued in this fashion to write a full solution (source code). It uses ReefJS for component rendering and state management, and you can try it for yourself right in your web browser. If you play against the online version I mentioned you’ll need to transpose the colours in your head: the physical version I play with the kids has pink and purple pegs, but the online one replaces these with brown and black.

Testing the solution

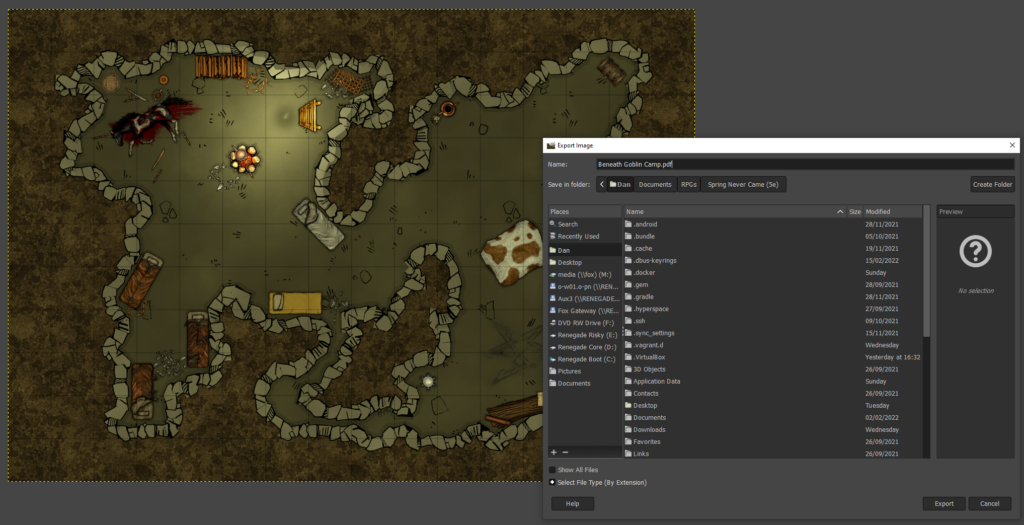

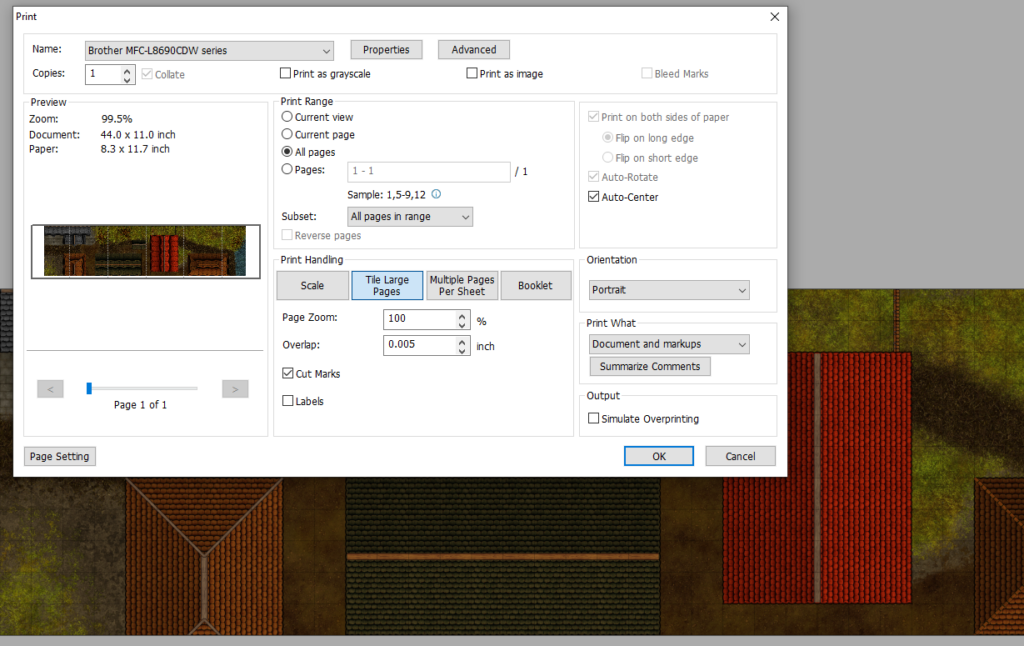

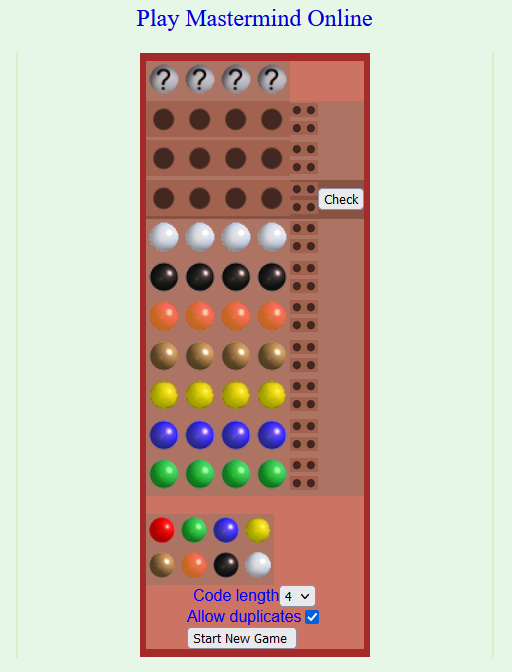

Let’s try it out against the online version:

As expected, my code works well-enough to win the game every time I’ve tried, both against computerised and in-person opponents. So – unless you’ve been actively thinking about the specifics of the algorithm I’ve employed – it might surprise you to discover that… my solution is very-much a suboptimal one!

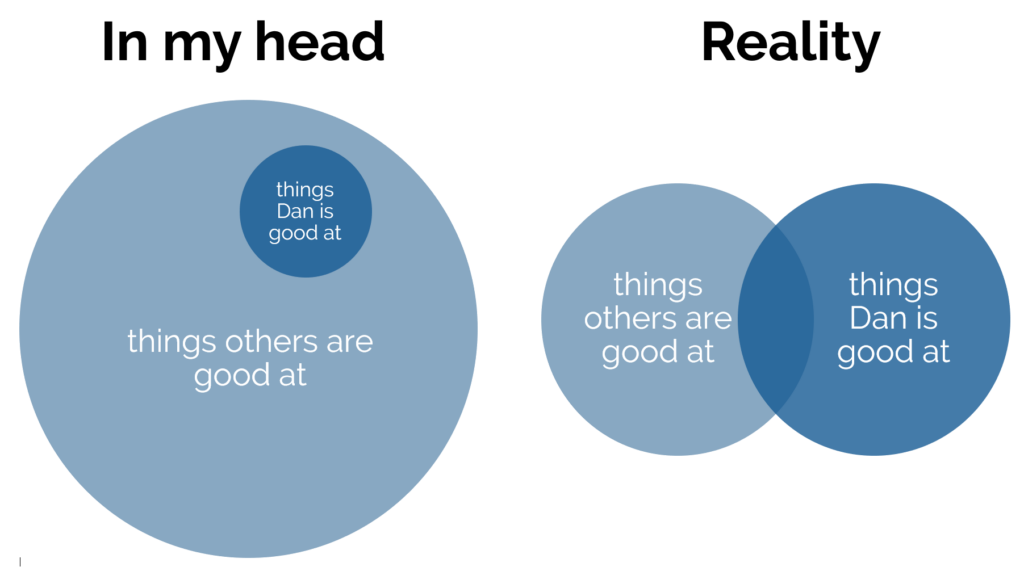

My solution is suboptimal

A couple of games in, the suboptimality of my solution became pretty visible. Sure, it still won every game, but it was a blunt instrument, and anybody who’s seriously thought about games like this can tell you why. You know how when you play e.g. Wordle (but not in “hard mode”) you sometimes want to type in a word that can’t possibly be the solution because it’s the best way to rule in (or out) certain key letters? This kind of strategic search space bisection reduces the mean number of guesses you need to solve the puzzle, and the same’s true in Mastermind. But because my solver will only propose guesses from the list of candidate solutions, it can’t make this kind of improvement.

Search space bisection is also used in my adverserial hangman game, but in this case the aim is to split the search space in such a way that no matter what guess a player makes, they always find themselves in the larger remaining portion of the search space, to maximise the number of guesses they have to make. Y’know, because it’s evil.

There are mathematically-derived heuristics to optimise Mastermind strategy. The first of these came from none other than Donald Knuth (legend of computer science, mathematics, and pipe organs) back in 1977. His solution, published at probably the height of the game’s popularity in the amazingly-named Journal of Recreational Mathematics, guarantees a solution to the six-colour version of the game within five guesses. Ville [2013] solved an optimal solution for a seven-colour variant, but demonstrated how rapidly the tree of possible moves grows and the need for early pruning – even with powerful modern computers – to conserve memory. It’s a very enjoyable and readable paper.

But for my purposes, it’s unnecessary. My solver routinely wins within six, maybe seven guesses, and by nonchalantly glancing at my phone in-between my guesses I can now reliably guess our children’s codes quickly and easily. In the end, that’s what this was all about.