I don’t really Twitter so much these days because like most social media it makes me either gloomy or extremely grumpy with the state of the world, but since I also lack the time to

bother blogging anywhere, here’s a ludicrously nerdy thread about a Dungeons & Dragons rumour.So, back in the days of AD&D 1st Edition your printed modules would often come with

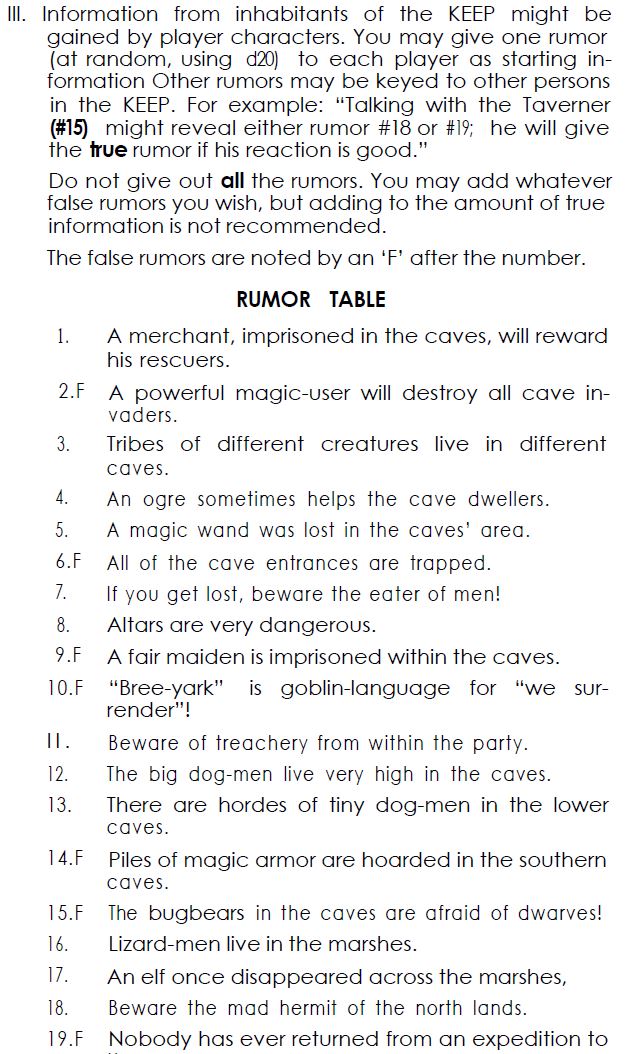

a table of Rumours. The idea was hearing rumours increased the depth of the world, so players didn’t feel like NPCs just winked into existence when they entered the Hydra’s Den

tavern & said “hi”.

But sometimes the rumours would be false, or exaggerated. That also added depth and had the bonus of ensuring that players didn’t take it for granted. OK, this guy in the red robe

*says* Kobolds are poisoning the iron ore, but is that at all plausible, or is it just a bad seam?

(Those of us without any friends, or at least without friends equally into D&D in the 80s & 90s, also got this experience because it was well-replicated in the TSR Gold Box

series of games, either in-game, or more-commonly through supplementary material in the boxes.

The supplementary materials often came in a separate “Journal” supplied in the box, & were a sort of additional layer of copy-protection because if the Game says “read Entry 19”,

your choice is either do so, or wait 25 years for the abandonware PDFs to hit archive.org.

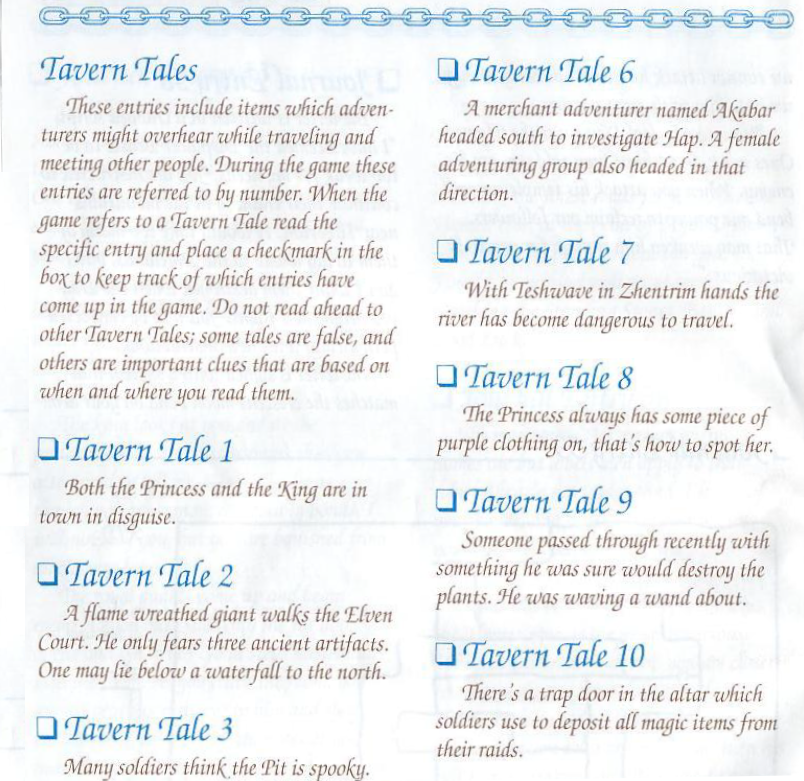

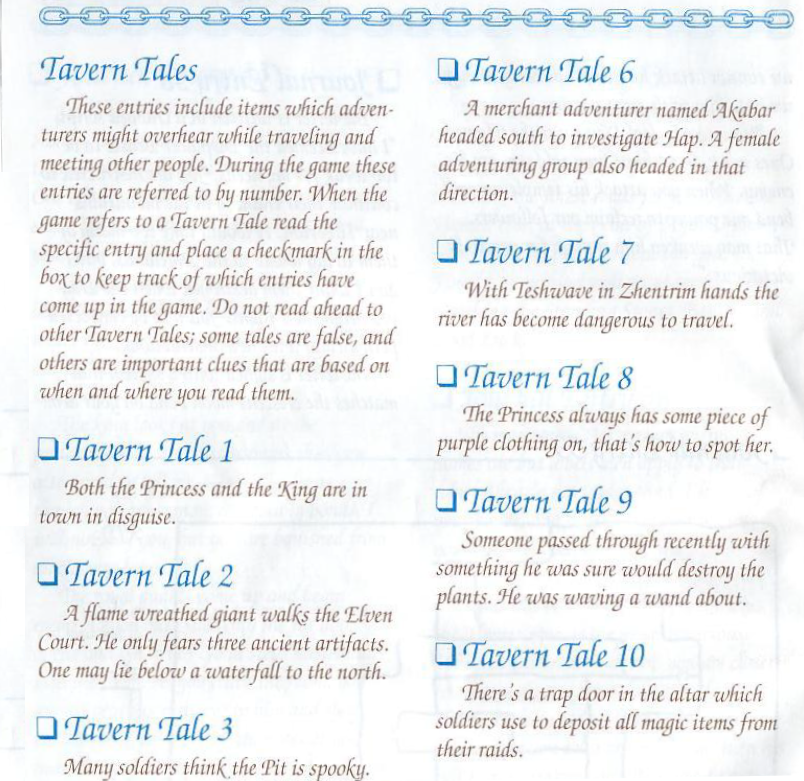

e.g., here’s the Traveller’s Tales from ‘Curse of the Azure Bonds’: note the subtlety of entries 1 and 8, about the Princess, sounding corroborative – maybe encouraging the party to

more deference around someone with purple in their clothes, though either or both might be false.)

Anyway, this only really existed in the TSR/SSI games because it was in the standard modules.

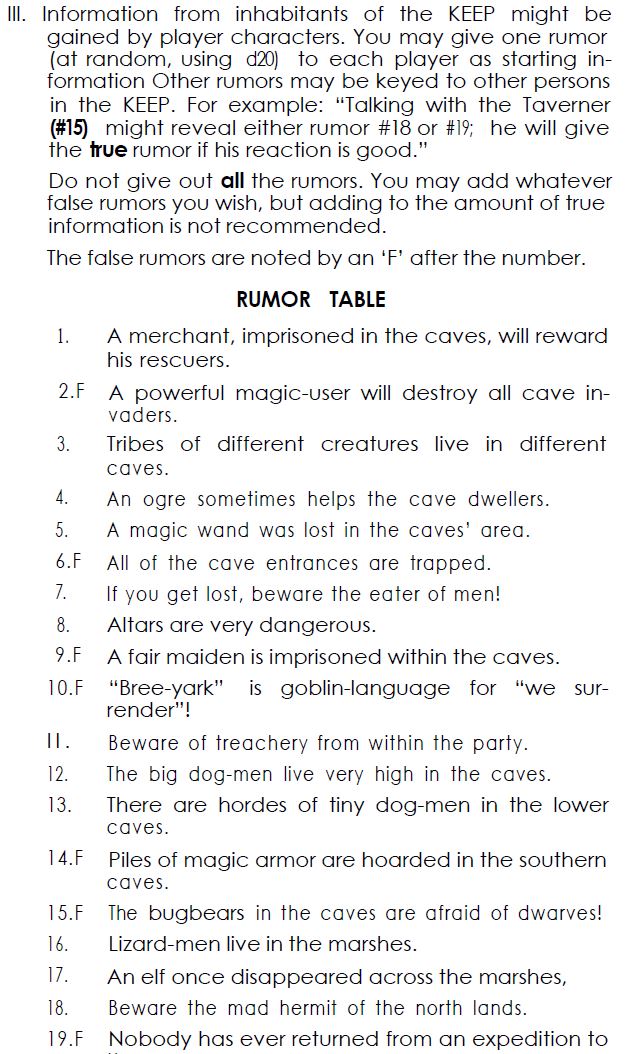

I was reminded of the rumour system when I was digging back into AD&D Module B2: The Keep on the Borderlands to borrow a bunch of content for a campaign I’ve just inherited (as

you do)

‘Keep on the Borderlands’ was by Gary Gygax himself, and suffers a bunch from the typical issues 1e had, none of which I’ll address here because I would please nobody. But the

rumours table is a really good example of the type – it gives players depth but not unfair advantages.

Now Keep on the Borderlands was a pretty big deal of a module back in the day. It was module B2, of the Basic Set, & it did some stuff really well, especially for new players – sort

of a 1980 equivalent of ‘Lost Mine of Phandelver’ today. Lots of players cut their teeth on it.

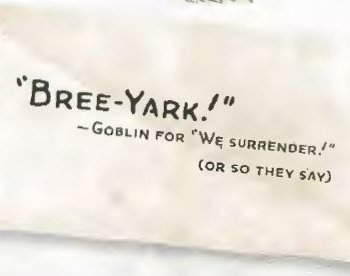

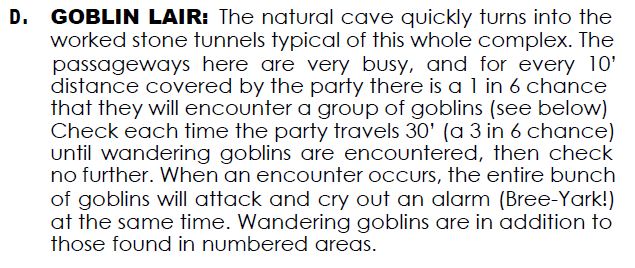

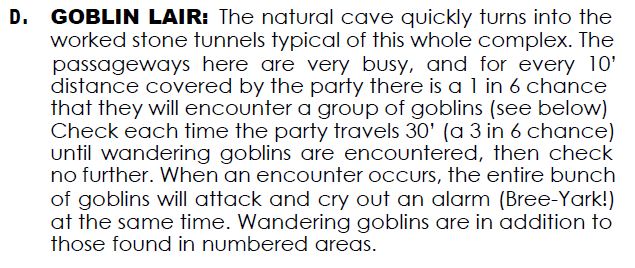

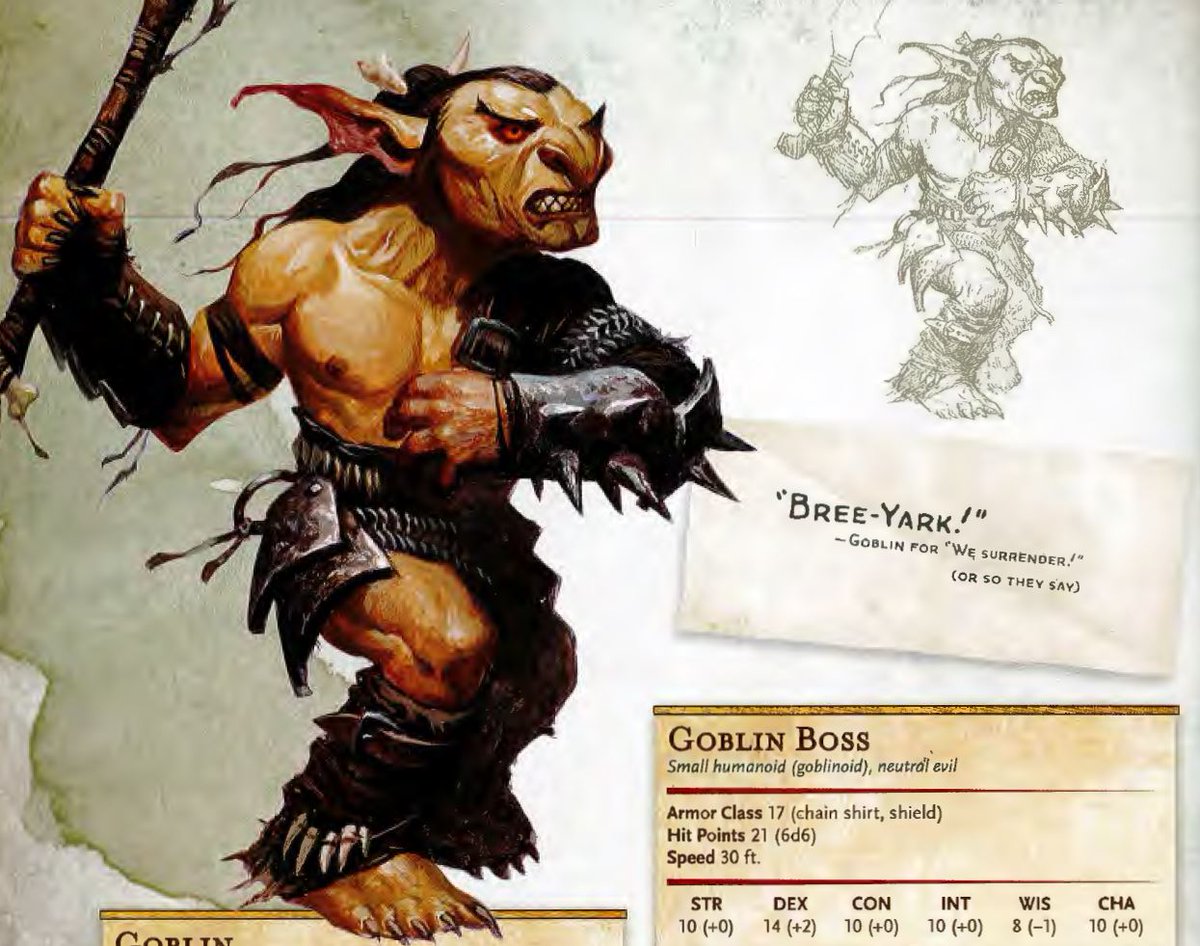

Rumour 10 – ‘”Bree-Yark” is goblin-language for “we surrender”!’ – is a false rumour, though the party doesn’t know that: whatever ‘Bree-yark’ means, it’s not “We Surrender”.

In fact, the module tells the DM it means “Hey, rube!!” and is used by goblins to sound the alarm.

(Spoilers here for the Goblin Lair in Location D of the Caves of Chaos, but when goblins on watch call out “Bree-yark!”, more goblins at #18 will bribe an ogre to come help attack

the party. (1e often imposed dynamic worlds by fiat, back when the world was young, the DMs green)

So lots of early DMs got to imagine the potential hilarity of the party arriving in the cave, hearing goblins apparently surrendering, & dropping their guard, never realising life

just got harder!

(It isn’t much hilarity, but in the 80s, as now, there was limited scope for joy)

Still – it’s a decent joke. Everyone believes “Bree-yark” is Goblin for surrender, but it isn’t really, that’s just a false rumour, spread by boastful drunks who’ve never seen a

goblin in real life anyway.

So much for 1st Edition AD&D, I guess.

…except:

It’s 2014. The wheel of time turns, ages come and pass, and Grapple rules don’t so much become legend as “remain completely incomprehensible”. Now every new adventurer carries a

Field Marshall’s baton in their knapsack, ‘cos tracking encumbrance is for chumps, & D&D 5e launches.

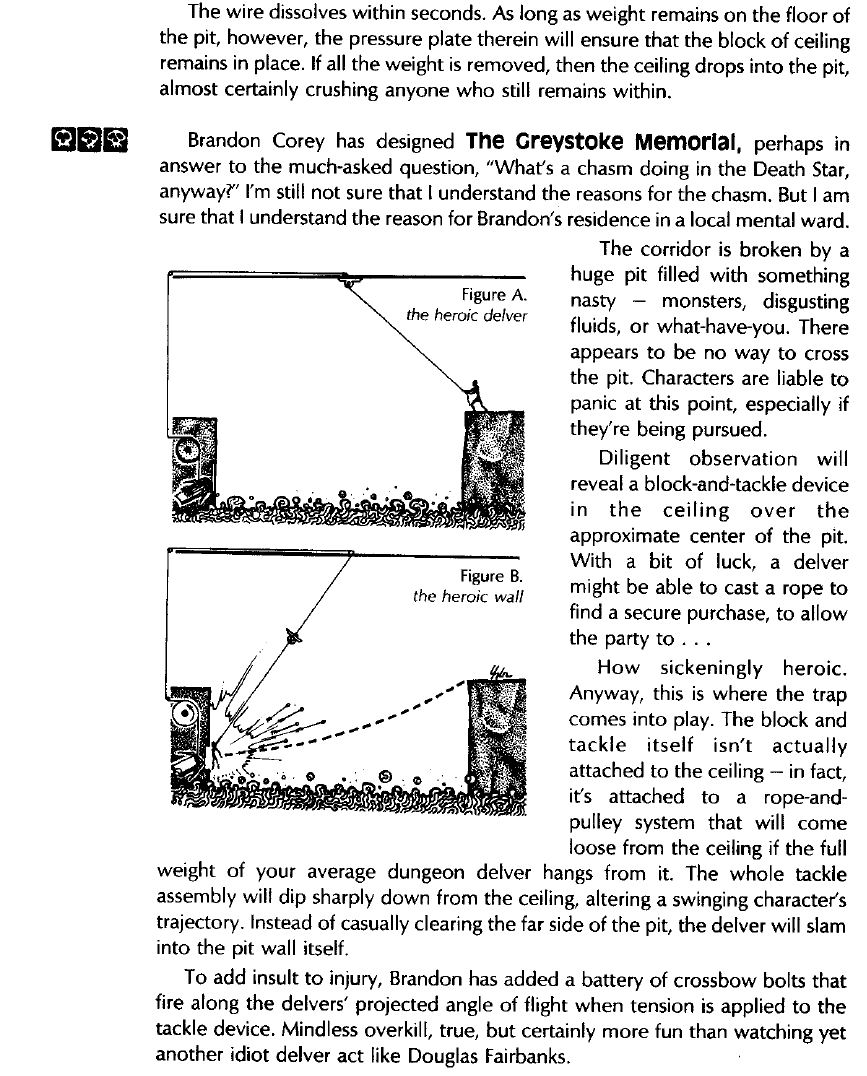

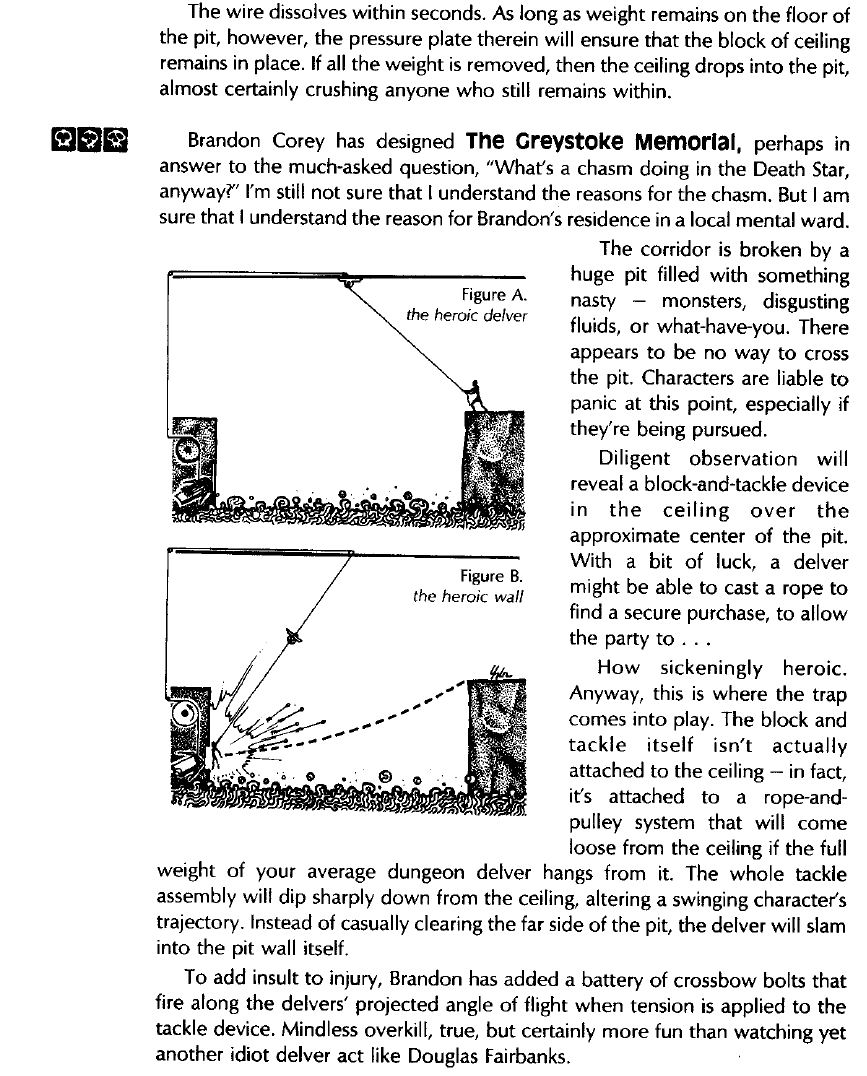

(While I’m doing archaeology, take a moment in this fast-forward to enjoy the glorious madness of the Grimtooth’s Traps series, which popped up in ’81 & features brilliantly

inventive nastiness to spring on players who aren’t too attached to their character sheets. Or friends.)

So, 5e launches, to a lot of stick in some circles (I never knew a version of D&D that didn’t: probably some wazzock in 1971 ranted that the codified Fantasy Supplement rules in

‘Chainmail’ “beTraYs rEaL FaNs!” and sold out the hobby, but at least they couldn’t whinge on Reddit)

…but someone involved in 5e is has conjured the most obscurely brilliant bit of ultra-specific nerd humour I have seen in years.

Y’see, 5e modules don’t really do Rumour Tables or “If the party X, then Y, else Z” – DMs create dynamic worlds on the fly. (Hopefully).

So you’d think there’s no more chance of hilarious moments where the Goblins start yelling “Bree-Yark!” and Magnus Rushes In only to be shocked to find a well-bribed and

high-Challenge Rating ogre running obediently up from Location E.22.

But you would think (slightly) wrong.

Because although 5e modules don’t do rumours the like 1e did, the Monster Manual does do flavour text – it’s usually a snippet of lore, or a word from a famous scholar, or advice

from an adventurer who encountered the monster but lived to tell the tale. It provides fluffy depth.

And, actually, I say “it’s usually” but I’ve just checked and every bit of flavourtext I can find in the Monster Manual is either By A Scholar, From a Book, An Adventurer’s Tale, or

a Monster Describing Itself…

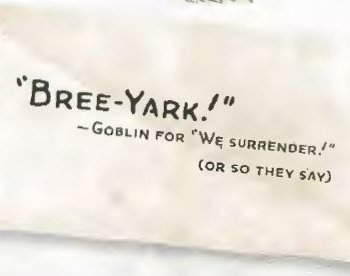

…with one single exception: the flavourtext on the entry for Goblins, which isn’t attributed to anybody or anything, but is just the claim that “Bree-Yark!” means “we surrender!”

This isn’t attributed to any source. Nobody in-lore has a citation for this. It’s just something “they say”. A genuine 1st Edition rumour just chilling out in the 5th edition

Monster Manual three decades after B2 landed.

Glorious. Well played, @Wizards. Very well played.