This checkin to geohash 2020-09-09 51 -1 reflects a geohashing expedition. See more of Dan's hash logs.

Location

Edge of a field bounded by Letcombe Brook, over the A338 from Landmead Solar Farm.

Participants

Plans

We’re discussing the possibility of a Subdivision geohash achievement for people who’ve reached every “X in a Y”, and Fippe pointed out that I’m only a hash in the Vale of White Horse from being able to claim such an achievement for Oxfordshire’s regions. And then this hashpoint appears right in the Vale of White Horse: it’s like it’s an omen!

Technically it’s a workday so this might have to be a lunchtime expedition, but I think that might be workable. I’ve got an electric vehicle with a hundred-and-something miles worth of batteries in the tank and it looks like there might be a lay-by nearby the hashpoint (with a geocache in it!): I can drive down there at lunchtime, walk carefully back up the main road, and try to get to the hashpoint!

Expedition

I worked hard to clear an hour of my day to take a trip, then jumped in my (new) electric car and set off towards the hashpoint. As I passed Newbridge I briefly considered stopping and checking up on my geocache there but feeling pressed for time I decided to push on. I parked in the lay-by where GC5XHJG is apparently hidden but couldn’t find it: I didn’t search for long because the farmer in the adjacent field was watching me with suspicion and I figured that anyway I could hunt for it on the way back.

Walking along the A338 was treacherous! There are no paths, only a verge covered in thick grass and spiky plants, and a significant number of the larger vehicles (and virtually all of the motorbikes) didn’t seem to be obeying the 60mph speed limit!

Reaching the gate, I crawled under (reckoning that it’s probably there to stop vehicles and not humans) and wandered along the lane. I saw a red kite and a heron doing their thing before I reached the bridge, crossed Letcombe Brook, and followed the edge of the field. Stuffing my face with blackberries as I went, it wasn’t long before I reached the hashpoint on one edge of the field.

I took a short-cut back before realising that this would put me in the wrong place to leave a The Internet Was Here sign, so I doubled-back to place it on the gate I’d crawled under. Then I returned to the lay-by, where another car had just pulled up (right over the GZ of the geocache I’d hoped to find!) and didn’t seem to be going anywhere. Sadly I couldn’t wait around all day – I had work to do! – so I went home, following the satnav in the car in a route that resulted in a figure-of-eight tracklog.

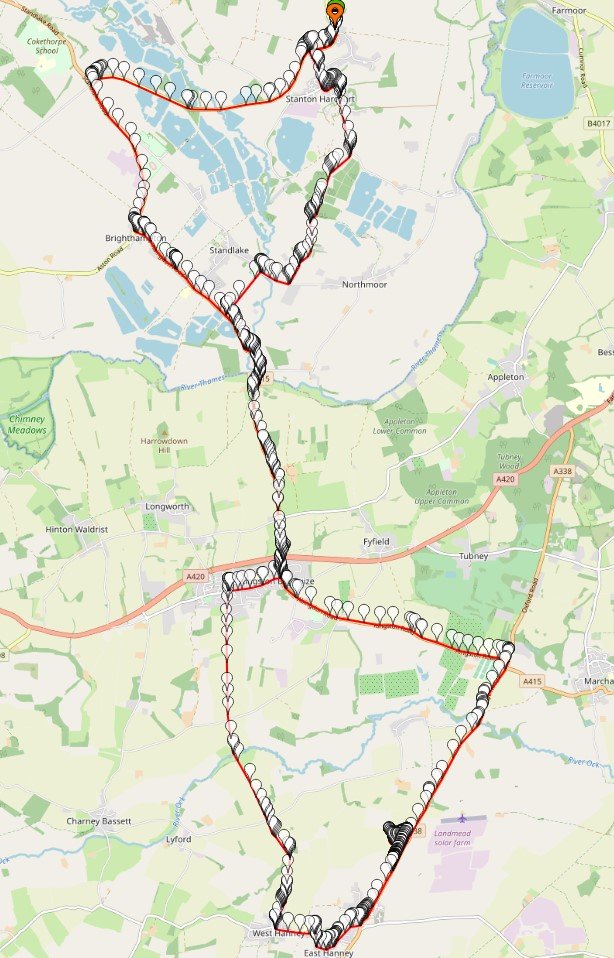

Tracklog

My GPS keeps a tracklog. Here you go:

Video

You can also watch it at: