How to guides

How to encrypt/decrypt with Enigma

We’ll start with a step-by-step guide to decrypting a known message. You can see the result of these steps in CyberChef here. Let’s say that our message is as follows:

XTSYN WAEUG EZALY NRQIM AMLZX MFUOD AWXLY LZCUZ QOQBQ JLCPK NDDRW FAnd that we’ve been told that a German service Enigma is in use with the following settings:

Rotors

III,II, andIV, reflectorB, ring settings (Ringstellung in German)KNG, plugboard (Steckerbrett)AH CO DE GZ IJ KM LQ NY PS TW, and finally the rotors are set toOPM.Enigma settings are generally given left-to-right. Therefore, you should ensure the 3-rotor Enigma is selected in the first dropdown menu, and then use the dropdown menus to put rotor

IIIin the 1st rotor slot,IIin the 2nd, andIVin the 3rd, and pickBin the reflector slot. In the ring setting and initial value boxes for the 1st rotor, putKandOrespectively,NandPin the 2nd, andGandMin the 3rd. Copy the plugboard settingsAH CO DE GZ IJ KM LQ NY PS TWinto the plugboard box. Finally, paste the message into the input window.The output window will now read as follows:

HELLO CYBER CHEFU SERST HISIS ATEST MESSA GEFOR THEDO CUMEN TATIO NThe Enigma machine doesn’t support any special characters, so there’s no support for spaces, and by default unsupported characters are removed and output is put into the traditional five-character groups. (You can turn this off by disabling “strict input”.) In some messages you may see X used to represent space.

Encrypting with Enigma is exactly the same as decrypting – if you copy the decrypted message back into the input box with the same recipe, you’ll get the original ciphertext back.

Plugboard, rotor and reflector specifications

The plugboard exchanges pairs of letters, and is specified as a space-separated list of those pairs. For example, with the plugboard

AB CD,Awill be exchanged forBand vice versa,CforD, and so forth. Letters that aren’t specified are not exchanged, but you can also specify, for example,AAto note thatAis not exchanged. A letter cannot be exchanged more than once. In standard late-war German military operating practice, ten pairs were used.You can enter your own components, rather than using the standard ones. A rotor is an arbitrary mapping between letters – the rotor specification used here is the letters the rotor maps A through Z to, so for example with the rotor

ESOVPZJAYQUIRHXLNFTGKDCMWB,Amaps toE,BtoS, and so forth. Each letter must appear exactly once. Additionally, rotors have a defined step point (the point or points in the rotor’s rotation at which the neighbouring rotor is stepped) – these are specified using a<followed by the letters at which the step happens.Reflectors, like the plugboard, exchange pairs of letters, so they are entered the same way. However, letters cannot map to themselves.

How to encrypt/decrypt with Typex

The Typex machine is very similar to Enigma. There are a few important differences from a user perspective:

- Five rotors are used.

- Rotor wirings cores can be inserted into the rotors backwards.

- The input plugboard (on models which had one) is more complicated, allowing arbitrary letter mappings, which means it functions like, and is entered like, a rotor.

- There was an additional plugboard which allowed rewiring of the reflector: this is supported by simply editing the specified reflector.

Like Enigma, Typex only supports enciphering/deciphering the letters A-Z. However, the keyboard was marked up with a standardised way of representing numbers and symbols using only the letters. You can enable emulation of these keyboard modes in the operation configuration. Note that this needs to know whether the message is being encrypted or decrypted.

How to attack Enigma using the Bombe

Let’s take the message from the first example, and try and decrypt it without knowing the settings in advance. Here’s the message again:

XTSYN WAEUG EZALY NRQIM AMLZX MFUOD AWXLY LZCUZ QOQBQ JLCPK NDDRW FLet’s assume to start with that we know the rotors used were

III,II, andIV, and reflectorB, but that we know no other settings. Put the ciphertext in the input window and the Bombe operation in your recipe, and choose the correct rotors and reflector. We need one additional piece of information to attack the message: a “crib”. This is a section of known plaintext for the message. If we know something about what the message is likely to contain, we can guess possible cribs.We can also eliminate some cribs by using the property that Enigma cannot encipher a letter as itself. For example, let’s say our first guess for a crib is that the message begins with “Hello world”. If we enter

HELLO WORLDinto the crib box, it will inform us that the crib is invalid, as theWinHELLO WORLDcorresponds to aWin the ciphertext. (Note that spaces in the input and crib are ignored – they’re included here for readability.) You can see this in CyberChef hereLet’s try “Hello CyberChef” as a crib instead. If we enter

HELLO CYBER CHEF, the operation will run and we’ll be presented with some information about the run, followed by a list of stops. You can see this here. Here you’ll notice that it saysBombe run on menu with 0 loops (2+ desirable)., and there are a large number of stops listed. The menu is built from the crib you’ve entered, and is a web linking ciphertext and plaintext letters. (If you’re maths inclined, this is a graph where letters – plain or ciphertext – are nodes and states of the Enigma machine are edges.) The machine performs better on menus which have loops in them – a letter maps to another to another and eventually returns to the first – and additionally on longer menus. However, menus that are too long risk failing because the Bombe doesn’t simulate the middle rotor stepping, and the longer the menu the more likely this is to have happened. Getting a good menu is a mixture of art and luck, and you may have to try a number of possible cribs before you get one that will produce useful results.

In this case, if we extend our crib by a single character to

HELLO CYBER CHEFU, we get a loop in the menu (thatUmaps to aYin the ciphertext, theYin the second cipher block maps toA, theAin the third ciphertext block maps toE, and theEin the second crib block maps back toU). We immediately get a manageable number of results. You can see this here. Each result gives a set of rotor initial values and a set of identified plugboard wirings. Extending the crib further toHELLO CYBER CHEFU SERproduces a single result, and it has also recovered eight of the ten plugboard wires and identified four of the six letters which are not wired. You can see this here.We now have two things left to do:

- Recover the remaining plugboard settings.

- Recover the ring settings.

This will need to be done manually.

Set up an Enigma operation with these settings. Leave the ring positions set to

Afor the moment, so from top to bottom we have rotorIIIat initial valueE, rotorIIatC, and rotorIVatG, reflectorB, and plugboardDE AH BB CO FF GZ LQ NY PS RR TW UU.You can see this here. You will immediately notice that the output is not the same as the decryption preview from the Bombe operation! Only the first three characters –

HEL– decrypt correctly. This is because the middle rotor stepping was ignored by the Bombe. You can correct this by adjusting the ring position and initial value on the right-hand rotor in sync. They are currentlyAandGrespectively. Advance both by one toBandH, and you’ll find that now only the first two characters decrypt correctly.Keep trying settings until most of the message is legible. You won’t be able to get the whole message correct, but for example at

FandL, which you can see here, our message now looks like:

HELLO CYBER CHEFU SERTC HVSJS QTEST KESSA GEFOR THEDO VUKEB TKMZM TAt this point we can recover the remaining plugboard settings. The only letters which are not known in the plugboard are

J K V X M I, of which two will be unconnected and two pairs connected. By inspecting the ciphertext and partially decrypted plaintext and trying pairs, we find that connectingIJandKMresults, as you can see here, in:

HELLO CYBER CHEFU SERST HISIS ATEST MESSA GEFOR THEDO CUMEO TMKZK TThis is looking pretty good. We can now fine tune our ring settings. Adjusting the right-hand rotor to

GandMgives, as you can see here,

HELLO CYBER CHEFU SERST HISIS ATEST MESSA GEFOR THEDO CUMEN WMKZK Twhich is the best we can get with only adjustments to the first rotor. You now need to adjust the second rotor. Here, you’ll find that anything from

DandFtoZandBgives the correct decryption, for example here. It’s not possible to determine the exact original settings from only this message. In practice, for the real Enigma and real Bombe, this step was achieved via methods that exploited the Enigma network operating procedures, but this is beyond the scope of this document.What if I don’t know the rotors?

You’ll need the “Multiple Bombe” operation for this. You can define a set of rotors to choose from – the standard WW2 German military Enigma configurations are provided or you can define your own – and it’ll run the Bombe against every possible combination. This will take up to a few hours for an attack against every possible configuration of the four-rotor Naval Enigma! You should run a single Bombe first to make sure your menu is good before attempting a multi-Bombe run.

You can see an example of using the Multiple Bombe operation to attack the above example message without knowing the rotor order in advance here.

What if I get far too many stops?

Use a longer or different crib. Try to find one that produces loops in the menu.

What if I get no stops, or only incorrect stops?

Are you sure your crib is correct? Try alternative cribs.

What if I know my crib is right, but I still don’t get any stops?

The middle rotor has probably stepped during the encipherment of your crib. Try a shorter or different crib.

How things work

How Enigma works

We won’t go into the full history of Enigma and all its variants here, but as a brief overview of how the machine works:

Enigma uses a series of letter->letter conversions to produce ciphertext from plaintext. It is symmetric, such that the same series of operations on the ciphertext recovers the original plaintext.

The bulk of the conversions are implemented in “rotors”, which are just an arbitrary mapping from the letters A-Z to the same letters in a different order. Additionally, to enforce the symmetry, a reflector is used, which is a symmetric paired mapping of letters (that is, if a given reflector maps X to Y, the converse is also true). These are combined such that a letter is mapped through three different rotors, the reflector, and then back through the same three rotors in reverse.

To avoid Enigma being a simple Caesar cipher, the rotors rotate (or “step”) between enciphering letters, changing the effective mappings. The right rotor steps on every letter, and additionally defines a letter (or later, letters) at which the adjacent (middle) rotor will be stepped. Likewise, the middle rotor defines a point at which the left rotor steps. (A mechanical issue known as the double-stepping anomaly means that the middle rotor actually steps twice when the left hand rotor steps.)

The German military Enigma adds a plugboard, which is a configurable pair mapping of letters (similar to the reflector, but not requiring that every letter is exchanged) applied before the first rotor (and thus also after passing through all the rotors and the reflector).

It also adds a ring setting, which allows the stepping point to be adjusted.

Later in the war, the Naval Enigma added a fourth rotor. This rotor does not step during operation. (The fourth rotor is thinner than the others, and fits alongside a thin reflector, meaning this rotor is not interchangeable with the others on a real Enigma.)

There were a number of other variants and additions to Enigma which are not currently supported here, as well as different Enigma networks using the same basic hardware but different rotors (which are supported by supplying your own rotor configurations).

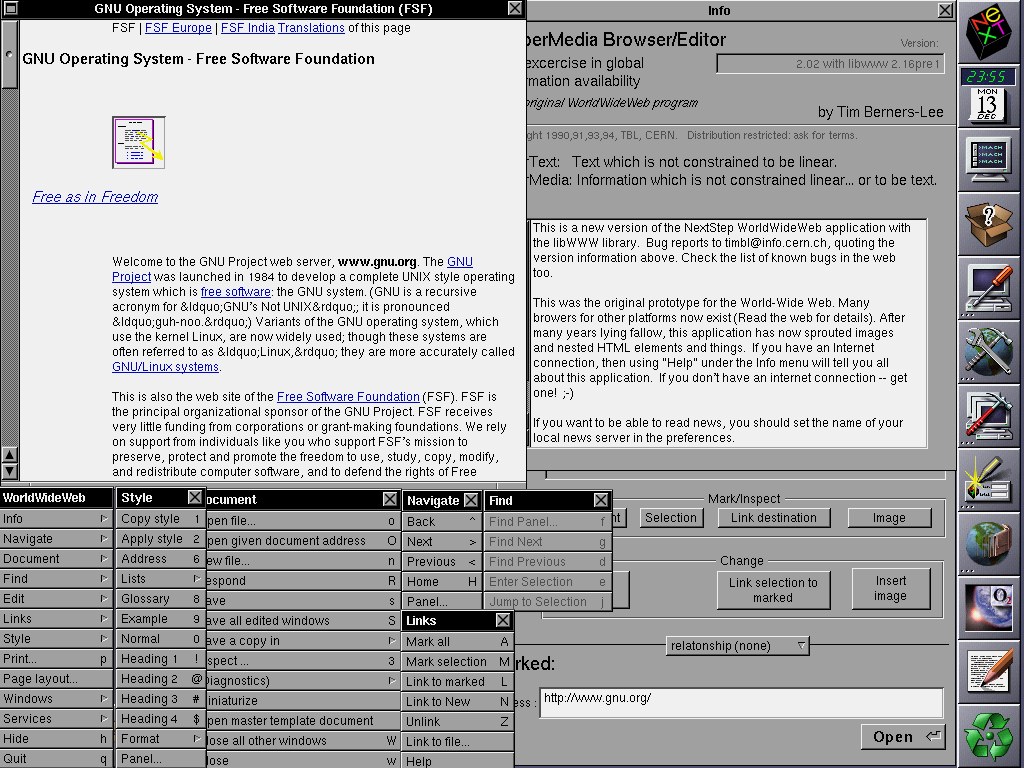

How Typex works

Typex is a clone of Enigma, with a few changes implemented to improve security. It uses five rotors rather than three, and the rightmost two are static. Each rotor has more stepping points. Additionally, the rotor design is slightly different: the wiring for each rotor is in a removable core, which sits in a rotor housing that has the ring setting and stepping notches. This means each rotor has the same stepping points, and the rotor cores can be inserted backwards, effectively doubling the number of rotor choices.

Later models (from the Mark 22, which is the variant we simulate here) added two plugboards: an input plugboard, which allowed arbitrary letter mappings (rather than just pair switches) and thus functioned similarly to a configurable extra static rotor, and a reflector plugboard, which allowed rewiring the reflector.

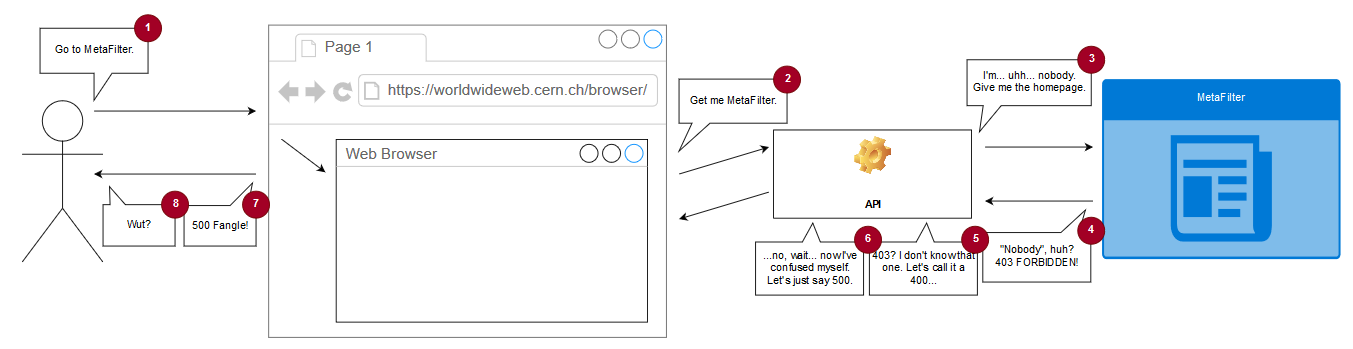

How the Bombe works

The Bombe is a mechanism for efficiently testing and discarding possible rotor positions, given some ciphertext and known plaintext. It exploits the symmetry of Enigma and the reciprocal (pairwise) nature of the plugboard to do this regardless of the plugboard settings. Effectively, the machine makes a series of guesses about the rotor positions and plugboard settings and for each guess it checks to see if there are any contradictions (e.g. if it finds that, with its guessed settings, the letter

Awould need to be connected to bothBandCon the plugboard, that’s impossible, and these settings cannot be right). This is implemented via careful connection of electrical wires through a group of simulated Enigma machines.A full explanation of the Bombe’s operation is beyond the scope of this document – you can read the source code, and the authors also recommend Graham Ellsbury’s Bombe explanation, which is very clearly diagrammed.

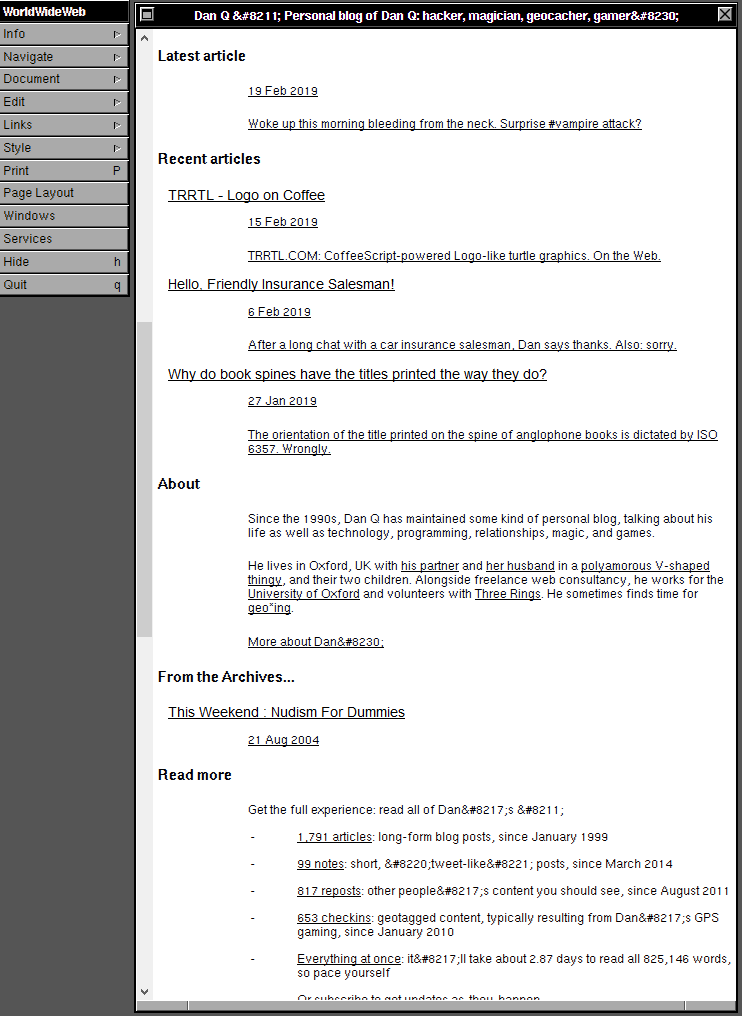

Implementation in CyberChef

Enigma/Typex

Enigma and Typex were implemented from documentation of their functionality.

Enigma rotor and reflector settings are from GCHQ’s documentation of known Enigma wirings. We currently simulate all basic versions of the German Service Enigma; most other versions should be possible by manually entering the rotor wirings. There are a few models of Enigma, or attachments for the Service Enigma, which we don’t currently simulate. The operation was tested against some of GCHQ’s working examples of Enigma machines. Output should be letter-for-letter identical to a real German Service Enigma. Note that some Enigma models used numbered rather than lettered rotors – we’ve chosen to stick with the easier-to-use lettered rotors.

There were a number of different Typex versions over the years. We implement the Mark 22, which is backwards compatible with some (but not completely with all, as some early variants supported case sensitivity) older Typex models. GCHQ also has a partially working Mark 22 Typex. This was used to test the plugboards and mechanics of the machine. Typex rotor settings were changed regularly, and none have ever been published, so a test against real rotors was not possible. An example set of rotors have been randomly generated for use in the Typex operation. Some additional information on the internal functionality was provided by the Bombe Rebuild Project.

The Bombe

The Bombe was likewise implemented on the basis of documentation of the attack and the machine. The Bombe Rebuild Project at the National Museum of Computing answered a number of technical questions about the machine and its operating procedures, and helped test our results against their working hardware Bombe, for which the authors would like to extend our thanks.

Constructing menus from cribs in a manner that most efficiently used the Bombe hardware was another difficult step of operating the real Bombes. We have chosen to generate the menu automatically from the provided crib, ignore some hardware constraints of the real Bombe (e.g. making best use of the number of available Enigmas in the Bombe hardware; we simply simulate as many as are necessary), and accept that occasionally the menu selected automatically may not always be the optimal choice. This should be rare, and we felt that manual menu creation would be hard to build an interface for, and would add extra barriers to users experimenting with the Bombe.

The output of the real Bombe is optimised for manual verification using the checking machine, and additionally has some quirks (the rotor wirings are rotated by, depending on the rotor, between one and three steps compared to the Enigma rotors). Therefore, the output given is the ring position, and a correction depending on the rotor needs to be applied to the initial value, setting it to

Wfor rotor V,Xfor rotor IV, andYfor all other rotors. We felt that this would require too much explanation in CyberChef, so the output of CyberChef’s Bombe operation is the initial value for each rotor, with the ring positions set toA, required to decrypt the ciphertext starting at the beginning of the crib. The actual stops are the same. This would not have caused problems at Bletchley Park, as operators working with the Bombe would never have dealt with a real or simulated Enigma, and vice versa.By default the checking machine is run automatically and stops which fail silently discarded. This can be disabled in the operation configuration, which will cause it to output all stops from the actual Bombe hardware instead. (In this case you only get one stecker pair, rather than the set identified by the checking machine.)

Optimisation

A three-rotor Bombe run (which tests 17,576 rotor positions and takes about 15-20 minutes on original Turing Bombe hardware) completes in about a fifth of a second in our tests. A four-rotor Bombe run takes about 5 seconds to try all 456,976 states. This also took about 20 minutes on the four-rotor US Navy Bombe (which rotates about 30 times faster than the Turing Bombe!). CyberChef operations run single-threaded in browser JavaScript.

We have tried to remain fairly faithful to the implementation of the real Bombe, rather than a from-scratch implementation of the underlying attack. There is one small deviation from “correct” behaviour: the real Bombe spins the slow rotor on a real Enigma fastest. We instead spin the fast rotor on an Enigma fastest. This means that all the other rotors in the entire Bombe are in the same state for the 26 steps of the fast rotor and then step forward: this means we can compute the 13 possible routes through the lower two/three rotors and reflector (symmetry means there are only 13 routes) once every 26 ticks and then save them. This does not affect where the machine stops, but it does affect the order in which those stops are generated.

The fast rotors repeat each others’ states: in the 26 steps of the fast rotor between steps of the middle rotor, each of the scramblers in the complete Bombe will occupy each state once. This means we can once again store each state when we hit them and reuse them when the other scramblers rotate through the same states.

Note also that it is not necessary to complete the energisation of all wires: as soon as 26 wires in the test register are lit, the state is invalid and processing can be aborted.

The above simplifications reduce the runtime of the simulation by an order of magnitude.

If you have a large attack to run on a multiprocessor system – for example, the complete M4 Naval Enigma, which features 1344 possible choices of rotor and reflector configuration, each of which takes about 5 seconds – you can open multiple CyberChef tabs and have each run a subset of the work. For example, on a system with four or more processors, open four tabs with identical Multiple Bombe recipes, and set each tab to a different combination of 4th rotor and reflector (as there are two options for each). Leave the full set of eight primary rotors in each tab. This should complete the entire run in about half an hour on a sufficiently powerful system.

To celebrate their centenary, GCHQ have open-sourced very-faithful reimplementations of Enigma, Typex, and Bombe that you can run in your browser. That’s pretty cool, and a really interesting experimental toy for budding cryptographers and cryptanalysts!