Step 2: brave the fierce weather surrounding Storm Bert and head out into rural Ireland in search of a geohashpoint.

But first, the crucial step 1: a big ol’ bacon and egg sarnie for breakfast.

In his latest Last Month video, TomSka took the “is a hot dog a sandwich” argument into a whole new arena by saying:

I’m a firm believer that the sauce and toppings should go under the dog. And that way, I don’t have to put it all in my moustache when I eat it.

My initial reaction was: What the hell are you doing‽ They’re toppings, not… bottomings, I guess?

But on the other hand:

So yeah, I might try doing this. But if I do, I’m definitely going to start calling them “bottomings”.

A recent observation by Phil Gyford reminded me of a recurring thought I’ve had. He wrote:

While being driven around England it struck me that humans are currently like the filling in a sandwich between one slice of machine — the satnav — and another — the car. Before the invention of sandwiches the vehicle was simply a slice of machine with a human topping. But now it’s a sandwich, and the two machine slices are slowly squeezing out the human filling and will eventually be stuck directly together with nothing but a thin layer of API butter. Then the human will be a superfluous thing, perhaps a little gherkin on the side of the plate.

While we were driving I was reading the directions from a mapping app on my phone, with the sound off, checking the upcoming turns, and giving verbal directions to Mary, the driver. I was an extra layer of human garnish — perhaps some chutney or a sliced tomato — between the satnav slice and the driver filling.

What Phil’s describing is probably familiar to you: the experience of one or more humans acting as the go-between to allow two machines to communicate. If you’ve ever re-typed a document that was visible on another screen, read somebody a password over the phone, given directions from a digital map, used a pendrive to carry files between computers that weren’t talking to one another properly then you’ve done it: you’ve been the soft wet meaty middleware that bridged two already semi-automated (but not quite automated enough) systems.

This generally happens because of the lack of a common API (a communications protocol) between two systems. If your phone and your car could just talk it out then the car would know where to go all by itself! Or, until we get self-driving cars, it could at least provide the directions in a way that was appropriately-accessible to the driver: heads-up display, context-relative directions, or whatever.

It also sometimes happens when the computer-to-human interface isn’t good enough; for example I’ve often offered to navigate for a driver (and used my phone for the purpose) because I can add a layer of common sense. There’s no need for me to tell my buddy to take the second exit from every roundabout in Milton Keynes (did you know that the town has 930 of them?) – I can just tell them that I’ll let them know when they have to change road and trust that they’ll just keep going straight ahead until then.

Finally, we also sometimes find ourselves acting as a go-between to filter and improve information flow when the computers don’t have enough information to do better by themselves. I’ll use the fact that I can see the road conditions and the lane markings and the proposed route ahead to tell a driver to get into the right lane with an appropriate amount of warning. Or if the driver says “I can see signs to our destination now, I’ll just keep following them,” I can shut up unless something goes awry. Your in-car SatNav can’t do that because it can’t see and interpret the road ahead of you… at least not yet!

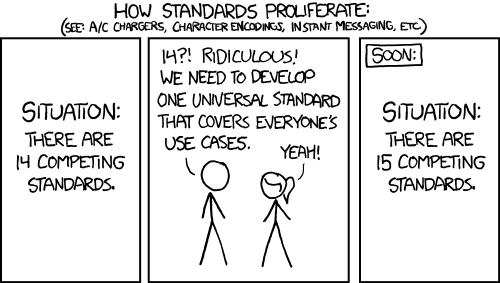

But here’s my thought: claims of an upcoming AI winter aside, it feels to me like we’re making faster progress in technologies related to human-computer interaction – voice and natural languages interfaces, popularised by virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa and by chatbots – than we are in technologies related to universal computer interoperability. Voice-controller computers are hip and exciting and attract a lot of investment but interoperable systems are hampered by two major things. The first thing holding back interoperability is business interests: for the longest while, for example, you couldn’t use Amazon Prime Video on a Google Chromecast for a long while because the two companies couldn’t play nice. The second thing is a lack of interest by manufacturers in developing open standards: every smart home appliance manufacturer wants you to use their app, and so your smart speaker manufacturer needs to implement code to talk to each and every one of them, and when they stop supporting one… well, suddenly your thermostat switches jumps permanently from smart mode to dumb mode.

A thing that annoys me is that from a technical perspective making an open standard should be a much easier task than making an AI that can understand what a human is asking for or drive a car safely or whatever we’re using them for this week. That’s not to say that technical standards aren’t difficult to get right – they absolutely are! – but we’ve been practising doing it for many, many decades! The very existence of the Internet over which you’ve been delivered this article is proof that computer interoperability is a solvable problem. For anybody who thinks that the interoperability brought about by the Internet was inevitable or didn’t take lots of hard work, I direct you to Darius Kazemi’s re-reading of the early standards discussions, which I first plugged a year ago; but the important thing is that people were working on it. That’s something we’re not really seeing in the Internet of Things space.

On our current trajectory, it’s absolutely possible that our virtual assistants will reach a point of becoming perfectly “human” communicators long before we can reach agreements about how they should communicate with one another. If that’s the case, those virtual assistants will probably fall back on using English-language voice communication as their lingua franca. In that case, it’s not unbelievable that ten to twenty years from now, the following series of events might occur:

I’m not saying that this is a desirable state of affairs. I’m not even convinced that it’s likely. But it’s certainly possible if IoT development keeps focussing on shiny friendly conversational interfaces at the expense of practical, powerful technical standards. Our already topsy-turvy technologies might get weirder before they get saner.

But if English does become the “universal API” for robot-to-robot communication, despite all engineering common sense, I suggest that we call it “sandwichware”.

This review of The Oxford Sandwich Company originally appeared on Google Maps. See more reviews by Dan.

Fresh sandwiches, panini and more made to order with a smile. Great value delicious food.

The entire infrastructure of our civilization – our entire species – is something that you can’t help but take for granted. Let’s make a cheese & pickle sandwich.

Find a grass whose seed, when crushed, yields a powdery flour rich in carbohydrates and proteins – any of the dozens of species of wheat will do, but there are plenty others besides. If you’re genuinely starting from scratch, you might find that it’s first worth your while cultivating and selectively breeding the cereal to improve its yield. Separate off the dry outer chaff from the seeds and grind them. You’ll also need some yeast, which you can acquire from the environment by letting water in which you’ve boiled vegetables sit in the warm for a few days, or by extracting it from the skins of fruits: alternatively, you can make use of yeast spores in the atmosphere by working slowly in the vicinity of fermenting sugars; e.g. somebody brewing alcohol. Combine the flour with some water and the yeast to make a dough, let it rise, then put it in a hot box for a while to bake it. There’s your bread.

Meanwhile, domesticate some cattle. You’ll need to have started this quite a while earlier. Specifically, you’re going to need cows that have recently weaned a calf, so they’re still lactating. Manipulate the teats of the cow to extract its milk, then heat it gently while stirring it. Assuming that you don’t have the resources to identify and separate lactococcus bacteria, you’ll want to be careful not to heat the milk enough that it kills any such bacteria already in it. Add an edible acid (lemon juice will do, assuming you’ve got access to lemons; alternatively you could use vinegar, which you’ll be needing later on anyway) to cause the milk to begin separating into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid part) – alternatively, if you’ve got spare unweaned calves that you can kill and harvest the stomachs of, you can use rennet. If you’ve got the hang of processing cotton, you can weave yourself a square of cheesecloth and use this as a filter. Once you’ve reduced the curds as far as possible, wrap it and squeeze it in a press (you can make this by putting weight on it) for a few days, turning occasionally. Then, cover it in an airtight seal of wax (you can get this by melting honeycombs taken from a beehive), and leave it for a month or two. There’s your cheese.

Harvest some fruit and vegetables, such as – depending on availability – swede, carrots, dates, onions, cauliflower, apples, courgettes, and tomatoes, and dice them. Boil together in vinegar with cloves, mustard, and sugar added until the hardest parts (typically the swede) are firm but not crunchy. Heat a sterile, airtight container, add the mixture, and seal. Leave for a couple of weeks. Oh: you don’t have vinegar? No problem: first you’re going to need alcohol, which you can produce from fruit – apples are probably easiest; grapes are another popular choice – and yeast: just combine the two and give it a few weeks. Now, to turn that into vinegar, keep it at just over room temperature for several more weeks, stirring regularly to aerate it. Seriously: if you thought that learning to milk a cow was hard, you should have given up long before now. Anyway: there’s your pickle.

You’ll also want some butter, but by this point you’re used to a little work. Assuming you don’t have access to a centrifuge, the traditional thing to do next is to leave it sitting in a shallow pan for about 24 hours, then skimming off the top – congratulations, you’ve got cream (the remaining milk is now what you would call skimmed milk; I suggest you have yourself a cool glass of it while you start working on the next bit). Put the cream into a bowl with a pinch of salt and work it, keeping it as cool as possible while you do so, as if you were trying to make whipped cream… but keep going! If you whip it for long enough it’ll gradually become more and more solid: drain it of the excess liquid (this is buttermilk), and then form it into a ball or block. Hurrah: you’ve got butter!

Finally, you can assemble your sandwich. Slide the bread, spread butter onto the slices, and put slices of the cheese and a spoonful of pickle in between them. That wasn’t so hard, now, was it?

You’ll be forgiven if you’re wondering why I’ve just shared with you the most drawn-out recipe imaginable, for something so simple as a cheese & pickle sandwich.

It’s just this: think about how much was involved in that process (and I didn’t even talk about making the tools you’d need). How complex is that process, compared to everything eaten by every other animal on the planet. Otters use rocks to get into shellfish, and chimpanzees use sticks to pull termites out of nests, but apart from these – and a few other exceptions – virtually no other species we’ve ever come across does anything more than picking or hunting for their food, and then eating it. We, on the other hand – even for our simplest processed foods – put a monumental amount of effort into making them the way they are.

And as if that weren’t complex enough, we go even further. We make different kinds of bread and cheese with different kinds of flour and milk, different processes, different ages; we make different brands of pickle and butter, and then argue on the Internet about which one is the best. We make sandwiches with egg mayonnaise (boiled eggs… in an emulsion of egg yolks and oil), with roasted or cured meats of different kinds of animals, with hummus (a remarkably complicated ingredient in its own right).

When you make yourself a sandwich, you’re standing upon the shoulders of the hundreds of generations that preceded you, and all of their peers. A collective knowledge passed down over millennia. In reality, nobody milks a cow because they want to make a sandwich: but that separation is only possible because of the enormous infrastructure we’ve built up in order to support the production and distribution of dairy goods.

We are, indeed, a very strange species.

But if you actually do have a go at making a sandwich based on this recipe, let me know how you get on.

There’s something that I just don’t understand about vegetarians. It’s something that I didn’t understand when I mercilessly teased them, and it’s something that I still don’t understand now that I am one:

What’s with the fake meat?

You know the stuff I’m talking about: stuff made out of mycoprotein or TVP or soya that’s specifically designed to emulate real meat in flavour (sometimes effectively) and texture (rarely so). Browse the chilled and frozen aisles of your local supermarket for their “vegetarian” section and you’ll find meatfree (although rarely vegan) alternatives to chicken, turkey, beef and pork, presented here in descending order of how convincing they are as a substitute.

Let’s be clear here: it’s not that I don’t see the point in faux meat. It has a few clear benefits: for a start, it makes vegetarianism more-approachable to omnivores who are considering it for the first time. I’ve tried meat substitutes on a number of occasions over the last couple of decades, and they’ve really improved over that time: even a meat-lover like me can be (partially) placated by the selection of substitutes available.

And while I slightly buy-in to the argument that the existence of these fake meats “glorifies” meat-eating, perhaps even to the extent as to under-sell vegetarianism as a poor substitute for the “real thing”, I don’t think that this is in itself the biggest problem with the fake meat industry. There’s a far bigger issue in question:

Why are we stopping here?

If we’re really trying here to make “fake meats”, then why are we setting our targets in-line with the commonly-eaten “real meats”? Why stop at chicken and turkey when we might as well make dodo-flavoured nut roasts and Quorn slices? Sure, they’re extinct, so we’ll probably never have real dodo meat: but there’s no reason that the manufacturers of artificial meats can’t have a go. There are dozens of accounts of the preparation and consumption of dodos, so we’d surely be able to emulate their flavour at least as well as we do the meats that we already produce substitutes for.

Why stop there? We might as well have tins of unicorn meat, too, a meal already familiar to those of us who’ve played more than our fair share of NetHack. How about dragons, or griffins, or the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary? If we’re going to make it up as we go along when we make artificial bacon, we might as well make it up as we go along when we make basilisk-burgers and salamander-sausages, too.

There’s a reason, of course, that we don’t see these more-imaginative meat substitutes. Many of the most loyal fake-meat customers are the kinds of people who don’t like to think about the connection between, for example, “chicken” (the foodstuff), and “chicken” (the clucking bird). To be fair, a lot of meat-eaters don’t like to think about this either, but I get the impression that it’s more-common among vegetarians.

But seriously, though: I think they’re missing a trick, here. Who wouldn’t love to eat artificial pegasus-pâté?

This story actually relates to an event that happened in mid-2010, but I only recently got around to finishing writing about it.

Once upon a time there was a boy named Dan.

Dan lives in a big house with his friends Ruth and JTA.

Dan lives in a big house with his friends Ruth and JTA.

(their other friend, Paul, lives in the house, too… but he isn’t in this story)

(their other friend, Paul, lives in the house, too… but he isn’t in this story)

One day, Dan and Ruth and JTA went on an adventure. They packed up a picnic with all their favourite

foods.

One day, Dan and Ruth and JTA went on an adventure. They packed up a picnic with all their favourite

foods.

Big soft sandwiches, teeny-tiny sausages, cheese-with-holes-in, and a big box of chocolates. Then

they got onto a bus.

Big soft sandwiches, teeny-tiny sausages, cheese-with-holes-in, and a big box of chocolates. Then

they got onto a bus.

Soon, they saw a big, wide river. “Let’s get off here,” said Ruth. JTA pressed the button to tell the

bus driver to stop.

Soon, they saw a big, wide river. “Let’s get off here,” said Ruth. JTA pressed the button to tell the

bus driver to stop.

At the river, there was a man with all kinds of boats: boats with pedals, boats with paddles, and

boats with poles.

At the river, there was a man with all kinds of boats: boats with pedals, boats with paddles, and

boats with poles.

“Can we borrow one of your boats?” Dan asked the man.

“Can we borrow one of your boats?” Dan asked the man.

“Okay,” he said, and gave Dan a long pole.

Ruth and JTA got into the boat and sat down. Dan stood up on the very back of the boat. It was

very wobbly!

Ruth and JTA got into the boat and sat down. Dan stood up on the very back of the boat. It was

very wobbly!

Dan used the pole to reach all the way down the bottom of the river, and pushed the boat along. It was hard work!

They found a shady tree in a park, stopped the boat, and ate their picnic.

They drank some fizzy wine and felt all bubbly and dizzy. Soon it was time to get back on the boat and go back along the river.

One time, Dan almost fell into the water! But luckily he didn’t, and he, Ruth and JTA got back safely.

And they all lived happily ever after.

There’s a right way to go for lunch during your break at work, and, if you’re in Aberystwyth, this is it.

Starter

I started in Scholars, where Matt (in the Hat) is spending the entire day as a birthday celebration. I treated Matt to a pint

of Guinness, and had a half myself, thereby giving myself probably a full lunch’s worth of calories. But never mind. Matt was trying to teach his friend Dave to play cribbage, with moderate success dulled only by the alcohol both had consumed. Matt’ll be in Scholars until they close, I don’t doubt, so if

you haven’t wished him a happy birthday yet, that’s where you’ll find him.

Main Course

I’ve recently discovered the sandwiches of Morgan’s, the butchers opposite Barclays on Great Darkgate Street. You go in there and mutter “beef” to the chap, who then

slices a generous bun and fills it with roast beef, a Yorkshire pudding, fried onions, and thick gravy. It’s a roast beef dinner… in a sandwich! Genius! Apart from the obvious mess it

makes to eat it, it’s fantastic.

I’ve recently discovered the sandwiches of Morgan’s, the butchers opposite Barclays on Great Darkgate Street. You go in there and mutter “beef” to the chap, who then

slices a generous bun and fills it with roast beef, a Yorkshire pudding, fried onions, and thick gravy. It’s a roast beef dinner… in a sandwich! Genius! Apart from the obvious mess it

makes to eat it, it’s fantastic.

Dessert

And to finish: back to The Hot Bread Shop on the corner of Cambrian Place and Chalybeate Street for a slice of orange cake. And now I’m very full. Marvellous.

We’re off on a picnic! Bryn, Claire, Paul and I are making sandwiches and we’re off up Pen Dinas to scoff them and watch the sunset. Which is nice.

It feels like springtime.