Finger Primer

The finger protocol, first standardised way back in 1977, is a lightweight directory system

for querying resources on a local or remote shared system. Despite barely being used today, it’s so well-established that virtually every modern desktop operating system – Windows,

MacOS, Linux etc. – comes with a copy of finger, giving it a similar ubiquity to web browsers! (If you haven’t yet, give it a go.)

If you were using a shared UNIX-like system in the 1970s through 1990s, you might run finger to see who else was logged on at the same time as you, finger

chris to get more information about Chris, or finger alice@example.net to look up the details of Alice on the server example.net. Its ability to transcend the

boundaries of different systems meant that it was, after a fashion, an example of an early decentralised social network!

I first actively used finger when I was a student at Aberystwyth University. The shared central computers osfa and

osfb supported it in what was a pretty typical way: users could add a .plan and/or .project file to their home directory and the contents of these

would be output to anybody using finger to look up that user, along with other information like what department they belonged to. I’m simulating from memory so this won’t be remotely

accurate, but broadly speaking it looked a little like this –

$ finger dlq9@aber.ac.uk

Login: dlq9 Name: Dan Q

Directory: /users/9/d/dlq9 Department: Computer Science

Project:

Working on my BEng Software Engineering.

Plan:

_______

---' ____)____

______) Finger me!

_____)

(____)

---.__(___)

It’s not just about a directory of people, though: you could finger printers to see what their queues were like, finger a time server to ask what time it was,

finger a vending machine to see what drinks it

had available… even finger for a weather forecast where you are (this one still works as shown below; try it for your own location!) –

$ finger oxford@graph.no

-= Meteogram for Oxford, Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom =-

'C Rain (mm)

12

11

10 ^^^=--=--

9^^^ ===

8 ^^^=== ====== ^^^

7 ====== ===============^^^ =--

6 =--=-----

5

4

3 | | | | | | | 1 mm

17 18 19 20 21 22 23 18/11 02 03 04 05 06 07_08_09_10_11_12_13_14 Hour

W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W Wind dir.

6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 6 6 6 5 5 4 4 4 4 5 6 6 5 5 Wind(m/s)

Legend left axis: - Sunny ^ Scattered = Clouded =V= Thunder # Fog

Legend right axis: | Rain ! Sleet * Snow

If you’d just like to play with finger, then finger.farm is a great starting point. They provide free finger hosting and they’re easy to use (try

finger dan@finger.farm to find me!). But I had something bigger in mind…

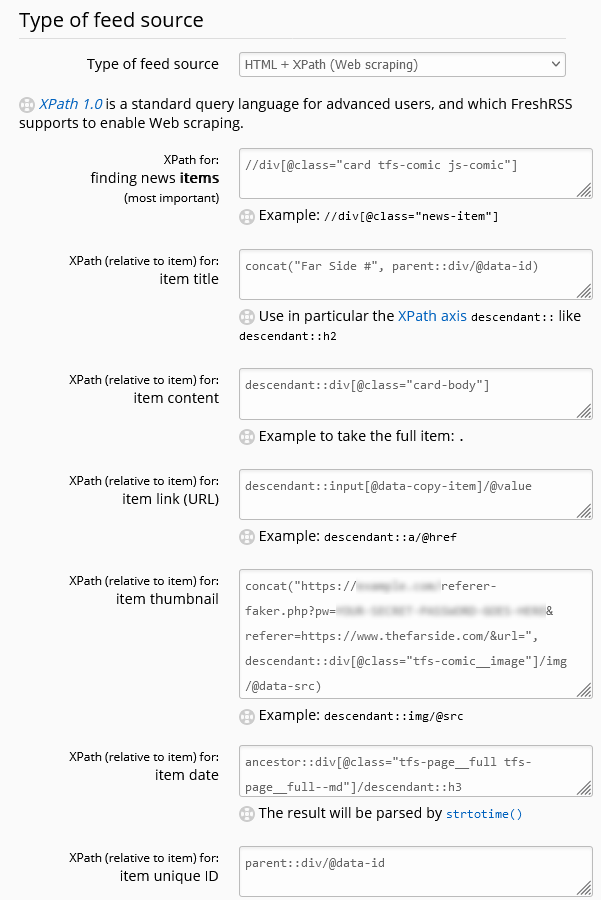

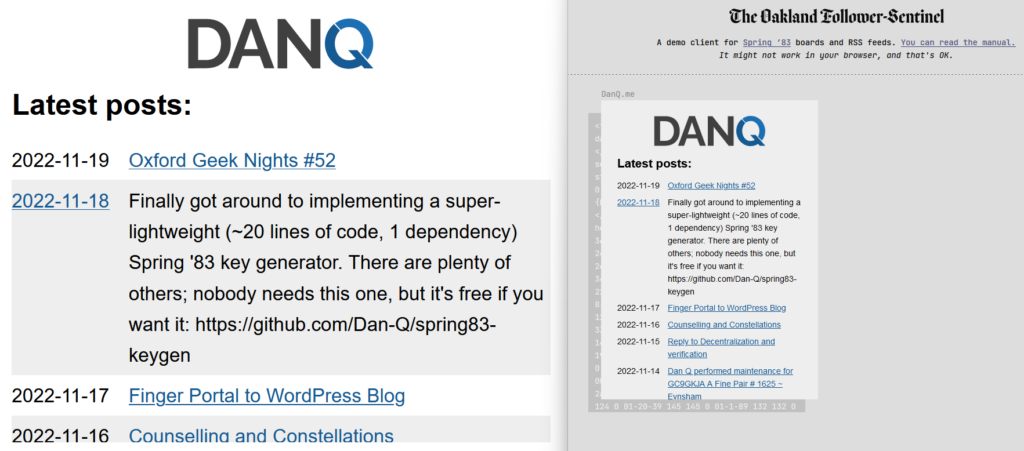

Fingering WordPress

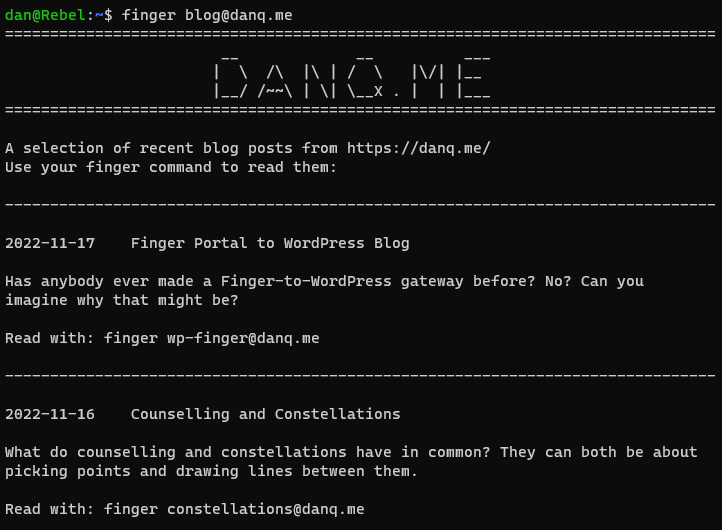

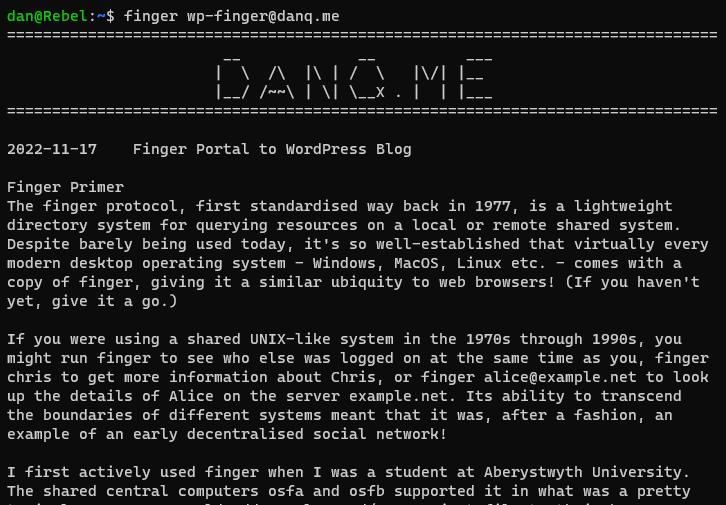

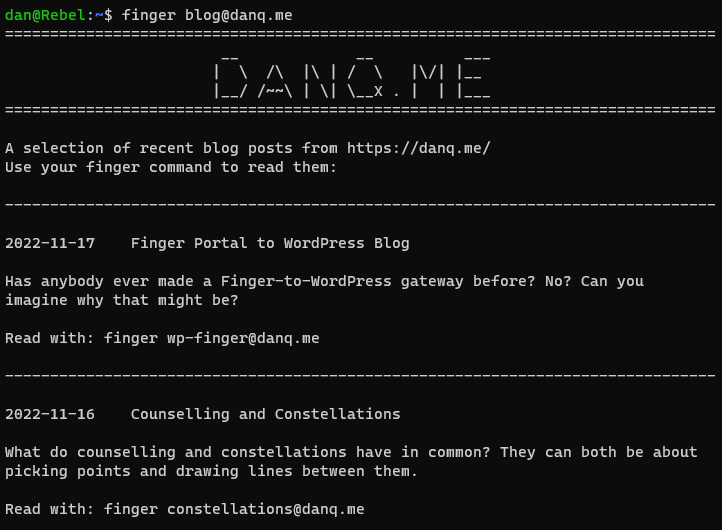

What if you could finger my blog. I.e. if you ran finger blog@danq.me you’d see a summary of some of my recent posts, along with additional

addresses you could finger to read the full content of each. This could be the world’s first finger-to-WordPress gateway; y’know, for

if you thought the world needed such a thing. Here’s how I did it:

-

Installed

efingerd; I’m using the Debian binaries.

- Opened a hole in the firewall on port 79 so the outside world could access it (

ufw allow 1965; utf reload).

- The default configuration for

efingerd acts like a “typical” finger server, but it’s highly programmable to make it “smarter”. I:

- Blanked

/etc/efingerd/list to prevent any output from “listing” the server (finger @danq.me).

- Replaced the contents of

/etc/efingerd/list and /etc/efingerd/nouser(which are run when a request matches, or doesn’t match, a user account name) with

a call to my script: /usr/local/bin/finger-to-wordpress "$3". $3 holds the username that was requested, so we can act on it.

- Created

/usr/local/bin/finger-to-wordpress – a Ruby program that either (a) lists a selection of posts or (b) returns a specific post (stripping the HTML

tags)

In future, I might use some extra tags or metadata to enhance finger-friendly WordPress posts. The infrastructure’s in place already (I already have tags that I use to make

certain kinds of content available only via certain media – shh!). You might rightly as what the point is of this entire enterprise, of course, and you’d be well within your

rights to ask such a question. But I think the best answer available is “because Dan”.

If you want to see my blog in a whole new way, give it a go: run finger blog@danq.me on your computer and follow the instructions.

![Browser debugger running document.evaluate('//li[@class="blog__post-preview"]', document).iterateNext() on Beverley's weblog and getting the first blog entry.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2022/09/debugger-select-from-xpath-1024x256.png)