Good morning, Oxfordshire! A freezing-fog farewell for me, this morning, as I get up early to catch a series of buses to the airport.

Author: Dan Q

Feed Readers Beat Doomscrolling

The news has, in general, been pretty terrible lately.

Like many folks, I’ve worked to narrow the focus of the things that I’m willing to care deeply about, because caring about many things is just too difficult when, y’know, nazis are trying to destroy them all.

I’ve got friends who’ve stopped consuming news media entirely. I’ve not felt the need to go so far, and I think the reason is that I already have a moderately-disciplined relationship with news. It’s relatively easy for me to regulate how much I’m exposed to all the crap news in the world and stay focussed and forward-looking.

The secret is that I get virtually all of my news… through my feed reader (some of it pre-filtered, e.g. my de-crappified BBC News feeds).

Without a feed reader, I can see how I might feel the need to “check the news” several times a day. Pick up my phone to check the time… glance at the news while I’m there… you know how to play that game, right?

But with a feed reader, I can treat my different groups of feeds like… periodicals. The news media I subscribe to get collated in my feed reader and I can read them once, maybe twice per day, just like a daily newspaper. If an article remains unread for several days then, unless I say otherwise, it’s configured to be quietly archived.

My current events are less like a firehose (or sewage pipe), and more like a bottle of (filtered) water.

Categorising my feeds means that I can see what my friends are doing almost-immediately, but I don’t have to be disturbed by anything else unless I want to be. Try getting that from a siloed social network!

Maybe sometimes I see a new breaking news story… perhaps 12 hours after you do. Is that such a big deal? In exchange, I get to apply filters of any kind I like to the news I read, and I get to read it as a “bundle”, missing (or not missing) as much or as little as I like.

On a scale from “healthy media consumption” to “endless doomscrolling”, proper use of a feed reader is way towards the healthy end.

If you stopped using feeds when Google tried to kill them, maybe it’s time to think again. The ecosystem’s alive and well, and having a one-stop place where you can enjoy the parts of the Web that are most-important to you, personally, in an ad-free, tracker-free, algorithmic-filtering-free space that you can make your very own… brings a special kind of peace that I can highly recommend.

Perfect bath

There are few moments of self-satisfaction so great as accidentally running a bath to both the perfect depth and the ideal temperature, after forgetting you’d started drawing the water at all.

Dog Tired

More castles and mazes

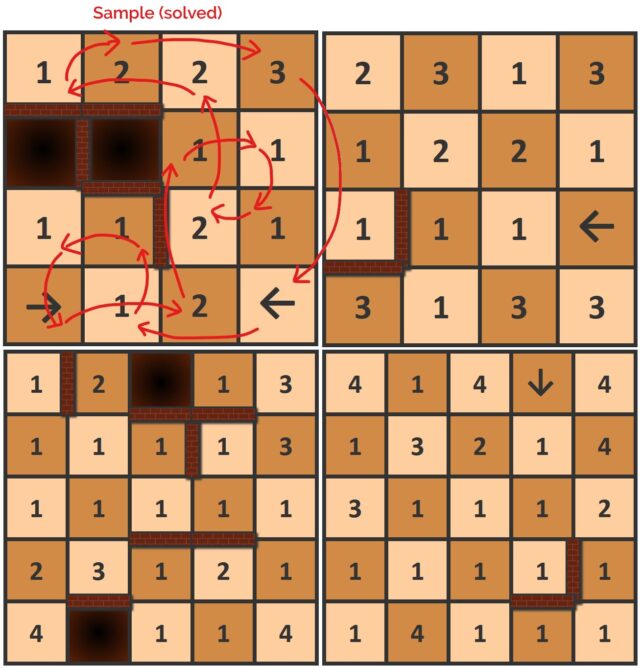

Made a little progress on the game idea I’d been experimenting with. The idea is to do find a series of orthogonal (like a rook in chess!) moves that land on every square exactly once each before returning to the start, dodging walls and jumping pits.

But the squares have arrows (limiting the direction you can move out of them) or numbers (specifying the distance you must travel from them).

Every board is solvable, starting from any square. There’ll be a playable version to use on your device (with helpful features like “undo”) sometime soon, but for now you can give them a go by hand, if you like this kind of puzzle!

WebDX: Does More Mean Better?

Enumerating Web features

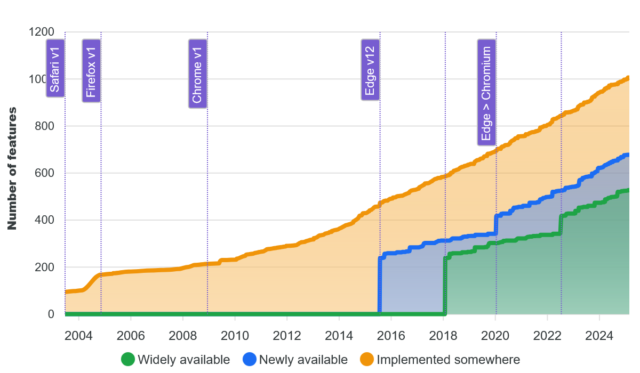

The W3C‘s WebDX Community Group this week announced that they’ve reached a milestone with their web-features project. The project is an effort to catalogue browser support for Web features, to establish an understanding of the baseline feature set that developers can rely on.

That’s great, and I’m in favour of the initiative. But I wonder about graphs like this one:

The graph shows the increase in time of the number of features available on the Web, broken down by how widespread they are implemented across the browser corpus.

The shape of that graph sort-of implies that… more features is better. And I’m not entirely convinced that’s true.

Does “more” imply “better”?

Don’t get me wrong, there are lots of Web features that are excellent. The kinds of things where it’s hard to remember how I did without them. CSS grids are for many purposes an improvement on flexboxes; flexboxes were massively better than floats; and floats were an enormous leap forwards compared to using tables for layout! The “new” HTML5 input types are wonderful, as are the revolutionary native elements for video, audio, etc. I’ll even sing the praises of some of the new JavaScript APIs (geolocation, web share, and push are particular highlights).

But it’s not some kind of universal truth that “more features means better developer experience”. It’s already the case, for example, that getting started as a Web developer is

harder than it once was, and I’d argue harder than it ought to be. There exist complexities nowadays that are barriers to entry. Like the places where the promise of a

progressively-enhanced Web has failed (they’re rare, but they exist). Or the sheer plethora of features that come with caveats to their use that simply must be learned (yes, you need a

<meta name="viewport">; no, you can’t rely on JS to produce content).

Meanwhile, there are technologies that were standardised, and that we did need, but that never took off. The <keygen> element never got

implemented into the then-dominant Internet Explorer (there were other implementation problems too, but this one’s the killer). This made it functionally useless, which meant that its

standard never evolved and grew. As a result, its implementation in other browsers stagnated and it was eventually deprecated. Had it been implemented properly and iterated on, we’d

could’ve had something like WebAuthn over a decade earlier.

Which I guess goes to show that “more features is better” is only true if they’re the right features. Perhaps there’s some way of tracking the changing landscape of developer experience on the Web that doesn’t simply count enumerate a baseline of widely-available features? I don’t know what it is, though!

A simple web

Mostly, the Web worked fine when it was simpler. And while some of the enhancements we’ve seen over the decades are indisputably an advancement, there are also plenty of places where we’ve let new technologies lead us astray. Third-party cookies appeared as a naive consequence of first-party ones, but came to be used to undermine everybody’s privacy. Dynamic DOM manipulation started out as a clever idea to help with things like form validation and now a significant number of websites can’t even show their images – or sometimes their text – unless their JavaScript code gets downloaded and interpreted successfully.

A blog post, news article, or even an eCommerce site or social networking platform doesn’t need the vast majority of the Web’s “new” features. Those features are important for some Web applications, but most of the time, we don’t need them. But somehow they end up being used anyway.

Whether or not the use of unnecessary new Web features is a net positive to developer experience is debatable. But it’s certainly not often to the benefit of user experience. And that’s what I care about.

This blog post, of course, can be accessed with minimal features: it’s even available over ultra-lightweight Gemini at gemini://danq.me/posts/webdx-does-more-mean-better/, and I’ve also written it as plain text on my plain text blog (did you know about that?).

Cherry blossom

When I was a child, we had a cherry blossom tree in our garden. In late Spring, as the flowers began to wilt, I’d enjoy shaking it to make flutters of pink confetti rain down around me.

This tree, though, spotted on the school run this morning, is very early in its bloom. It feels like a happy reminder that Spring is beginning.

Steam Email alt-text improvements

I noticed that automated emails from Steam weren’t doing alt-text very well. Some image links had no or inadequate alt-text. (Note that Steam don’t support opting for plain text rather than HTML emails.)

I’m fortunate enough to depend upon alt-text never-to-rarely. But I prefer not to load remote images, so I still benefit from alt-text.

I filled out a support request to Steam layout out the specific examples I’d found of where they weren’t doing very well, and stressing why it’s (morally, legally, etc.) important to do better.

And you know what: they quietly fixed it. When I received an email today telling me that something on my wishlist is on sale, it had reasonably-good alt-text throughout. Neat.

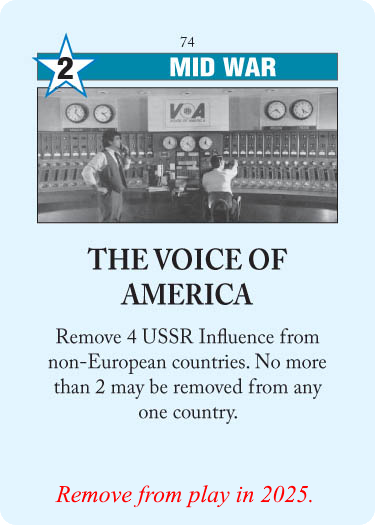

Voice of America

In light of Trump’s attempts to axe Voice of America, because it is, he claims, “anti-Trump” (and because he’s so insecure that he can’t stand the thought that taxpayer dollars might go to anybody who disagrees with him in any way, for any reason), I’ve produced a suggested update to the rules of Twilight Struggle for the inevitable 9th printing:

In the game, I mean.

Yet another blow to US soft power in order to appease the ego of convicted felon Donald Trump. Sigh.

Dan Q found GCAP4MF Church Micro 15127…Curbridge

This checkin to GCAP4MF Church Micro 15127...Curbridge reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

I had an errand to run in the Windrush Place estate on the other side of the A40, and the geopup needed a walk, so I opted to park the car over in Witney so my four-legged friend and I could walk the remaining way over to Curbridge and find this cache.

The first challenge was, of course, getting over the pedestrian-unfriendly roundabout and across be bridge to Curbridge, but the second challenge wasn’t much easier. Which bit of the church was the extension? It wasn’t immediately clear and we had to make a few guesses before our numbers lined up to anything believable.

Finally, we set off. The geohound went crazy, and I soon realised why: our route was taking us almost exactly past the doggy daycare she attends twice a week. It was strange enough for me to find myself at a GZ I pass several times a week, but it must have been even stranger for the doggo, whose keen nose could probably tell that we’d unexpectedly come by somewhere so familiar to her!

The coordinates were bang on and I soon had the cache in hand. Thanks for a lovely walk and the opportunity to explore on foot a place previously only familiar to me by car. SL, TFTC!

Work Slippers

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Last month my pest of a dog destroyed my slippers, and it was more-disruptive to my life than I would have anticipated.

Sure, they were just a pair of slippers1, but they’d become part of my routine, and their absence had an impact.

Routines are important, and that’s especially true when you work from home. After I first moved to Oxford and started doing entirely remote work for the first time, I found the transition challenging2. To feel more “normal”, I introduced an artificial “commute” into my day: going out of my front door and walking around the block in the morning, and then doing the same thing in reverse in the evening.

It turns out that in the 2020s my slippers had come to serve a similar purpose – “bookending” my day – as my artificial commute had over a decade earlier. I’d slip them on when I was at my desk and working, and slide them off when my workday was done. With my “work” desk being literally the same space as my “not work” desk, the slippers were a psychological reminder of which “mode” I was in. People talk about putting on “hats” as a metaphor for different roles and personas they hold, but for me… the distinction was literal footwear.

And so after a furry little monster (who for various reasons hadn’t had her customary walk yet that day and was probably feeling a little frustrated) destroyed my slippers… it actually tripped me up3. I’d be doing something work-related and my feet would go wandering, of their own accord, to try to find their comfortable slip-ons, and when they failed, my brain would be briefly tricked into glancing down to look for them, momentarily breaking my flow. Or I’d be distracted by something non-work-related and fail to get back into the zone without the warm, toe-hugging reminder of what I should be doing.

It wasn’t a huge impact. But it wasn’t nothing either.

So I got myself a new pair of slippers. They’re a different design, and I’m not so keen on the lack of an enclosed heel, but they solved the productivity and focus problem I was facing. It’s strange how such a little thing can have such a big impact.

Oh! And d’ya know what? This is my hundredth blog post of the year so far! Coming on only the 73rd day of the year, this is my fastest run at #100DaysToOffload yet (my previous best was last year, when I managed the same on 22 April). 73 is exactly a fifth of 365, so… I guess I’m on track for a mammoth 500 posts this year? Which would be my second-busiest blogging year ever, after 2018. Let’s see how I get on…4

Footnotes

1 They were actually quite a nice pair of slippers. JTA got them for me as a gift a few years back, and they lived either on my feet or under my desk ever since.

2 I was working remotely for a company where everybody else was working in-person. That kind of hybrid setup is a lot harder to do “right”, as many companies in this post-Covid-lockdowns age have discovered, and it’s understandable that I found it somewhat isolating. I’m glad to say that the experience of working for my current employer – who are entirely distributed – is much more-supportive.

3 Figuratively, not literally. Although I would probably have literally tripped over had I tried to wear the tattered remains of my shredded slippers!

4 Back when I did the Blog Questions Challenge I looked at my trajectory and estimated I wouldn’t hit a hundred this year until a week later than now, so maybe I’m… accelerating?

Castles and mazes

It’s not cheating if you write the video game solver yourself

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

I didn’t know how to solve the puzzle, but I did know how to write a computer program to solve it for me. That would probably be even more fun, and I could argue that it didn’t actually count as cheating. I didn’t want the solution to reveal itself to me before I’d had a chance to systematically hunt it down, so I dived across the room to turn off the console.

I wanted to have a shower but I was worried that if I did then inspiration might strike and I might figure out the answer myself. So I ran upstairs to my office, hit my Pomodoro timer, scrolled Twitter to warm up my brain, took a break, made a JIRA board, Slacked my wife a status update, no reply, she must be out of signal. Finally I fired up my preferred assistive professional tool. Time to have a real vacation.

…

Obviously, I’d be a fan of playing your single-player video game any damn way you like. But beyond that, I see Robert’s point: there are some puzzles that are just as much (or more) fun to write a program to solve than to solve as a human. Digital jigsaws would be an obvious and ongoing example, for me, but I’ve also enjoyed “solving” Hangman (not strictly a single-player game, but my “solution” isn’t really applicable to human opponents anyway), Mastermind (this is single-player, in my personal opinion – fight me! – the codemaster doesn’t technically have anything “real” to do; their only purpose is to hold secret information), and I never got into Sudoku principally because I found implementing a solver much more fun that being a solver.

Anyway: Robert’s post shows that he’s got too much time on his hands when his wife and kids are away, and it’s pretty fun.

Coaching in the Library

I decided to take my meeting with my coach today in our house’s new library, which my metamour JTA has recently been working hard on decorating, constructing, and filling with books. The room’s not quite finished, but it made for a brilliant space for a bit of quiet reflection and self-growth work.

(Incidentally: I might be treating “lives in a house with a library” as a measure of personal success. Like: this is what winning at life looks like, right? Because whatever else goes wrong, at least you can go hide in the library!)

Engagement

I’ve been trying to comment more on other people’s blogs. It’s tough, because comment forms continue to wane in popularity, and it’s not always clear who’ll accept Webmentions, but there’s often the option of a good old-fashioned email or a fediverse ping.

It occurred to me that I follow a significant number of personal blogs, and my privacy systems mean I’m a bit of a ghost to most analytics systems they might use, so the only way they’d ever know I was there would be if I said so.

Plus, the Internet is better when it’s social. There are some great people out there, and I’m enjoying meeting them!

(You’re welcome to throw comments, Webmentions, or emails my way, of course, too!)

![A notebook is held in front of terminal output. The terminal begins with 'Start position: [0,4]' and then shows a series of 5×5 grids containing numbers: one, labelled 'Route:', shows random grid of the numbers 0 through 24; the second, labelled 'Puzzle:', contains 1s, 2s, and 3s, corresponding perhaps to the orthagonal distances between consecutive numbers from the first grid; the third, whose title is obscured by the notebook, shows the same thing again but with 'walls' drawn in ASCII art between some of the numbers. The notebook in front contains hand-drawn sketches of similar grids with arrows "jumping" around between them.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2025/03/20250313_100059-640x487.jpg)