Enumerating Web features

The W3C‘s WebDX Community Group this week announced that they’ve reached a milestone with their web-features project. The project is an effort to catalogue browser support for Web features, to establish an understanding of the baseline feature set that developers can rely on.

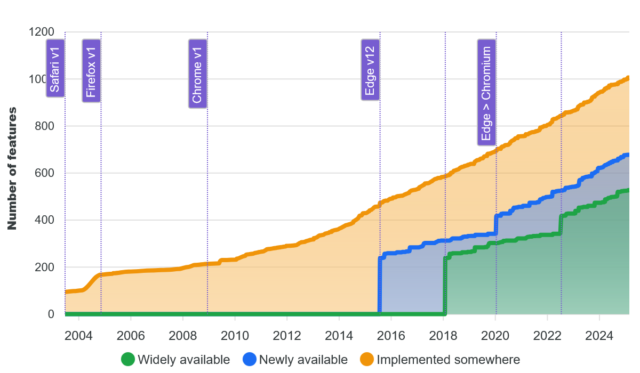

That’s great, and I’m in favour of the initiative. But I wonder about graphs like this one:

The graph shows the increase in time of the number of features available on the Web, broken down by how widespread they are implemented across the browser corpus.

The shape of that graph sort-of implies that… more features is better. And I’m not entirely convinced that’s true.

Does “more” imply “better”?

Don’t get me wrong, there are lots of Web features that are excellent. The kinds of things where it’s hard to remember how I did without them. CSS grids are for many purposes an improvement on flexboxes; flexboxes were massively better than floats; and floats were an enormous leap forwards compared to using tables for layout! The “new” HTML5 input types are wonderful, as are the revolutionary native elements for video, audio, etc. I’ll even sing the praises of some of the new JavaScript APIs (geolocation, web share, and push are particular highlights).

But it’s not some kind of universal truth that “more features means better developer experience”. It’s already the case, for example, that getting started as a Web developer is

harder than it once was, and I’d argue harder than it ought to be. There exist complexities nowadays that are barriers to entry. Like the places where the promise of a

progressively-enhanced Web has failed (they’re rare, but they exist). Or the sheer plethora of features that come with caveats to their use that simply must be learned (yes, you need a

<meta name="viewport">; no, you can’t rely on JS to produce content).

Meanwhile, there are technologies that were standardised, and that we did need, but that never took off. The <keygen> element never got

implemented into the then-dominant Internet Explorer (there were other implementation problems too, but this one’s the killer). This made it functionally useless, which meant that its

standard never evolved and grew. As a result, its implementation in other browsers stagnated and it was eventually deprecated. Had it been implemented properly and iterated on, we’d

could’ve had something like WebAuthn over a decade earlier.

Which I guess goes to show that “more features is better” is only true if they’re the right features. Perhaps there’s some way of tracking the changing landscape of developer experience on the Web that doesn’t simply count enumerate a baseline of widely-available features? I don’t know what it is, though!

A simple web

Mostly, the Web worked fine when it was simpler. And while some of the enhancements we’ve seen over the decades are indisputably an advancement, there are also plenty of places where we’ve let new technologies lead us astray. Third-party cookies appeared as a naive consequence of first-party ones, but came to be used to undermine everybody’s privacy. Dynamic DOM manipulation started out as a clever idea to help with things like form validation and now a significant number of websites can’t even show their images – or sometimes their text – unless their JavaScript code gets downloaded and interpreted successfully.

A blog post, news article, or even an eCommerce site or social networking platform doesn’t need the vast majority of the Web’s “new” features. Those features are important for some Web applications, but most of the time, we don’t need them. But somehow they end up being used anyway.

Whether or not the use of unnecessary new Web features is a net positive to developer experience is debatable. But it’s certainly not often to the benefit of user experience. And that’s what I care about.

This blog post, of course, can be accessed with minimal features: it’s even available over ultra-lightweight Gemini at gemini://danq.me/posts/webdx-does-more-mean-better/, and I’ve also written it as plain text on my plain text blog (did you know about that?).

0 comments