Today’s Hide And Seek With The Kids is brought to you by the Bishop’s Palace, St. David’s, Wales.

Tag: parenting

Note #26550

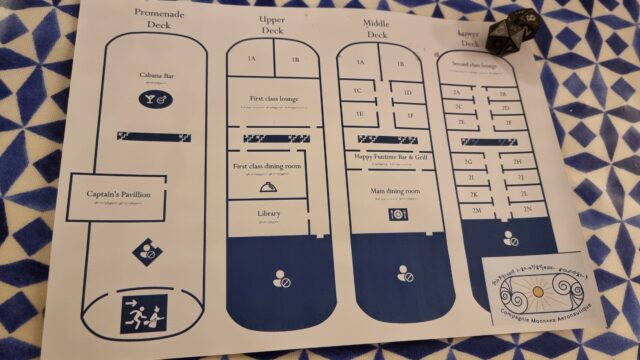

Map of the Titan

Y’all seemed to enjoy the “overworld” map I shared the other day, so here’s another “feelie” from my kids’ ongoing D&D campaign.

The party has just arranged for passage aboard a pioneering (and experimental) Elvish airship. Here’s a deck plan (only needs a “you are here” dot!) to help them get their bearings.

Family D&D’s Overworld Map

In preparation for Family D&D Night (and with thanks to my earlier guide to splicing maps together!), I’ve finally completed an expanded “overworld” map for our game world. So far, the kids have mostly hung around on the North coast of the Central Sea, but they’re picked up a hook that may take them all the way across to the other side… and beyond?

Banana for scale.

(If your GMing for kids, you probably already know this, but “feelies” go a long way. All the maps. All the scrolls. Maybe even some props. Go all in. They love it.)

Daily Brushing

8-year-old, looking like a haystack: “Why do I have to brush my hair? I did it yesterday!”

Giant strategy

Lake District art lesson

Note #26282

Unacceptable language

8-year-old, angry: Give me that fucking thing right now!

Me: [Child’s name]! That’s not an acceptable way to ask for something!

8-year-old, calmer: Sorry. PLEASE can you give me that fucking thing?

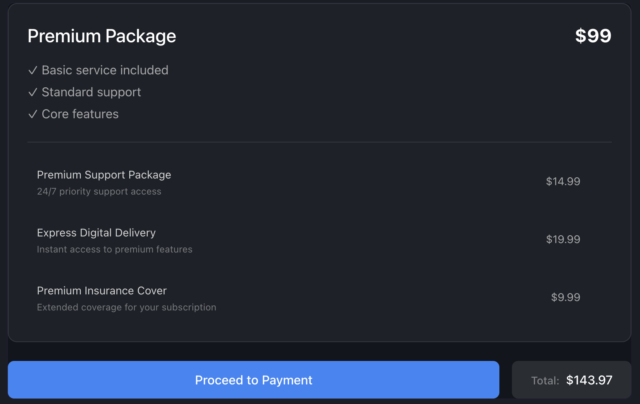

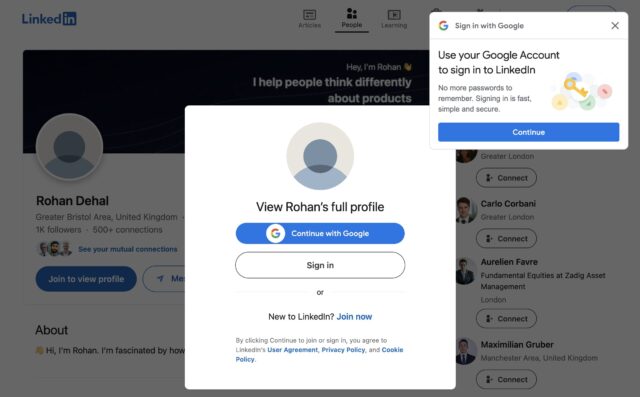

Dark Patterns Detective

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This was fun. A simple interactive demonstration of ten different dark patterns you’ve probably experienced online. I might use it as a vehicle for talking about such deceptive tactics with our eldest child, who’s now coming to an age where she starts to see these kinds of things.

After I finished exploring the dark patterns shown, I decided to find out more about the author and clicked the link in the footer, expecting to be taken to their personal web site. But instead, ironically, I came to a web page on a highly-recognisable site that’s infamous for its dark patterns: 🤣

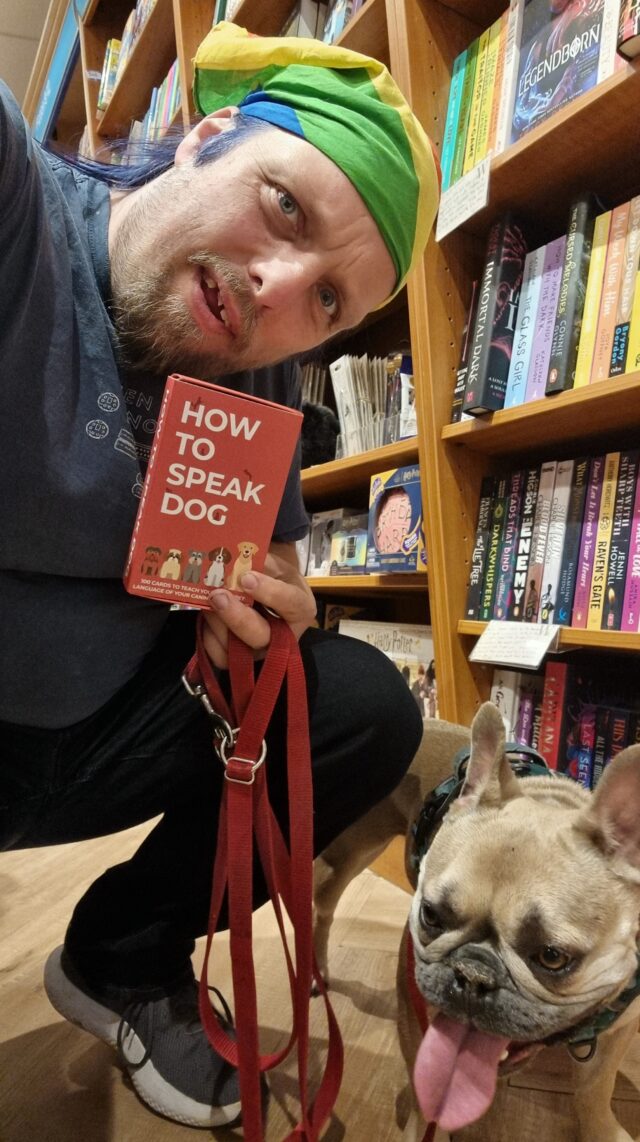

My Ball

Our beloved-but-slightly-thick dog will sometimes consent to playing fetch, but one of her favourite games to play is My Ball. Which is a bit like fetch, except that she won’t let go of the ball.

It’s not quite the same as tug-of-war, though. She doesn’t want you to pull the toy in a back-and-forth before, most-likely, giving up and letting her win1. Nor is My Ball a solo game: she’s not interested in sitting and simply chewing the ball, like some dogs do.

No, this is absolutely a participatory game. She’ll sit and whine for your attention to get you to come to another room. Or she’ll bring the toy in question (it doesn’t have to be a ball) and place it gently on your foot to get your attention.

Your role in this game is to want the ball. So long as you’re showing that you want the ball – occasionally reaching down to take it only for her to snatch it away at the last second, verbally asking if you can have it, or just looking enviously in its general direction – you’re playing your part in the game. Your presence and participation is essential, even as your role is entirely ceremonial.

Playing it, I find myself reminded of playing with the kids when they were toddlers. The eldest in particular enjoyed spending countless hours playing make-believe games in which the roles were tightly-scripted2. She’d tell me that, say, I was a talking badger or a grumpy dragon or an injured patient but immediately shoot down any effort to role-play my assigned character, telling me that I was “doing it wrong” if I didn’t act in exactly the unspoken way that she imagined my character ought to behave.

But the important thing to her was that I embodied the motivation that she assigned me. That I wanted the rabbits to stop digging too near to my burrow3 or the princess to stay in her cage4 or to lie down in my hospital bed and await the doctor’s eventual arrival5. Sometimes I didn’t need to do much, so long as I showed how I felt in the role I’d been assigned.

Somebody with much more acting experience and/or a deeper academic comprehension of the performing arts is going to appear in the comments and tell me why this is, probably.

But I guess what I mean to say is that playing with my dog sometimes reminds me of playing with a toddler. Which, just sometimes, I miss.

Footnotes

1 Alternatively, tug-of-war can see the human “win” and then throw the toy, leading to a game of fetch after all.

2 These games were, admittedly, much more-fun than the time she had me re-enact my father’s death with her.

3 “Grr, those pesky rabbits are stopping me sleeping.”

4 “I’ll just contentedly sit on my pile of treasure, I guess?”

5 Playing at being an injured patient was perhaps one of my favourite roles, especially after a night in which the little tyke had woken me a dozen times and yet still had some kind of tiny-human morning-zoomies. On at least one such occasion I’m pretty sure I actually fell asleep while the “doctor” finished her rounds of all the soft toys whose triage apparently put them ahead of me in the pecking order. Similarly, I always loved it when the kids’ games included a “naptime” component.

Note #25428

Note #25413

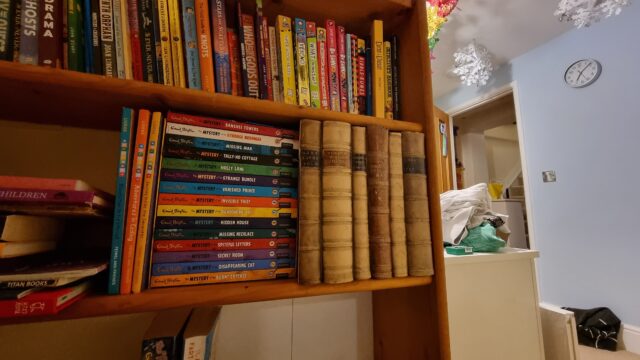

Building another secret cabinet

Earlier this year, after our loft conversion work, I built a secret cabinet into the bookshelves I constructed for my new bedroom. My 10-year-old was particularly taken with it1, and so I promised her that when she moved bedroom I’d build one for her.

My initial order of fake book fronts was damaged in transit but the excellent eBay seller I’d been dealing with immediately sent a comparable replacement. This had left me with a spare-but-damaged set of fake book fronts, but with a little gluing, sawing and filing I was able to turn them into a second usable fake cabinet front.

My 10-year-old’s fake cabinet isn’t quite as sophisticated as mine (no Raspberry Pi Zero, solenoids, or electronic locks) – you just have to know where it is and pull on the correct corner of it to release it – but she still thinks it’s pretty magical2.

A cut-down plank of plyboard stained the right colour, some offcuts of skirting board, a couple of butt hinges, some L-brackets, some bathroom mirror mounting tape, the fake book fronts, and an hour and a half’s work seems totally worth it to give a child the magical experience of a secret compartment in their bedroom. My carpentry’s improved since my one, too: this time I measured twice before cutting3 and it paid-off with a cleaner, straighter finish.

Footnotes

1 She was pretty impressed already at the secret cabinet, but perhaps more-so when she discovered that the fake book fronts I’d used were part of the set of The School for Good and Evil, the apparently-disappointing film version of one of her favourite series’ of books.

2 Which, frankly, it is. I wish I’d had a secret compartment in my bedroom bookshelves when I was her age!

3 Somebody should make a saying about that.

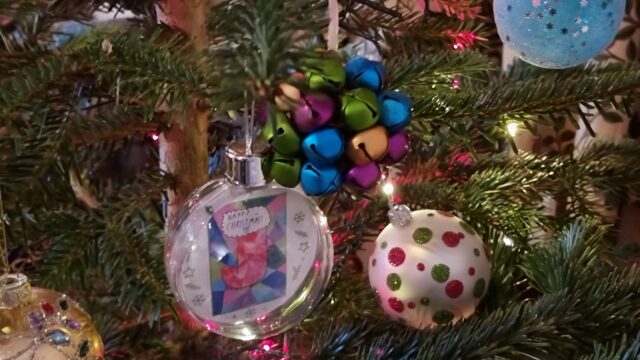

Babies and Baubles

For a long time now, every year we’ve encouraged our two children (now 10 and 8 years old) to each select one new bauble for our Christmas tree1. They get to do this at the shop adjoining the place from which we buy the tree, and it’s become a part of our annual Christmas traditions.

This approach to decoration: ad-hoc, at the whims of growing children, and spread across many years without any common theme or pattern, means that our tree is decorated in a way that

might be generously described as eclectic. Or might less-generously be described as malcoordinated!

But there’s something beautiful about a deliberately-constructed collection of disparate and disconnected parts.

I’m friends with a couple, for example, who’ve made a collection of the corks from the wine bottles from each of their anniversary celebrations, housed together into a strange showcase. There might be little to connect one bottle to the next, and to an outsider a collection of used stoppers might pass as junk, but for them – as for us – the meaning comes as a consequence of the very act of collecting.

Each ornament is an untold story. A story of a child wandering around the shelves of a Christmas-themed store, poking fingerprints onto every piece of glass they can find as they weigh

up which of the many options available to them is the most special to them this year.

And every year, at about this time, they get to relive their past tastes and fascinations as we pull out the old cardboard box and once again decorate our family’s strangely beautiful but mismatched tree.

It’s pretty great.

Footnotes

1 Sometimes each has made a bauble or similar decoration at their school or nursery, too. “One a year” isn’t a hard rule. But the key thing is, we’ve never since their births bought a set of baubles.