Some younger/hipper friends tell me that there was a thing going around on Instagram this week where people post photos of themselves aged 21.

I might not have any photos of myself aged 21! I certainly can’t find any digital ones…

It must sound weird to young folks nowadays, but prior to digital photography going mainstream in the 2000s (thanks in big part to the explosion of popularity of mobile phones), taking a photo took effort:

- Most folks didn’t carry their cameras everywhere with them, ready-to-go, so photography was much more-intentional.

- The capacity of a film only allowed you to take around 24 photos before you’d need to buy a new one and swap it out (which took much longer than swapping a memory card).

- You couldn’t even look at the photos you’d taken until they were developed, which you couldn’t do until you finished the roll of film and which took at least hours – more-realistically days – and incurred an additional cost.

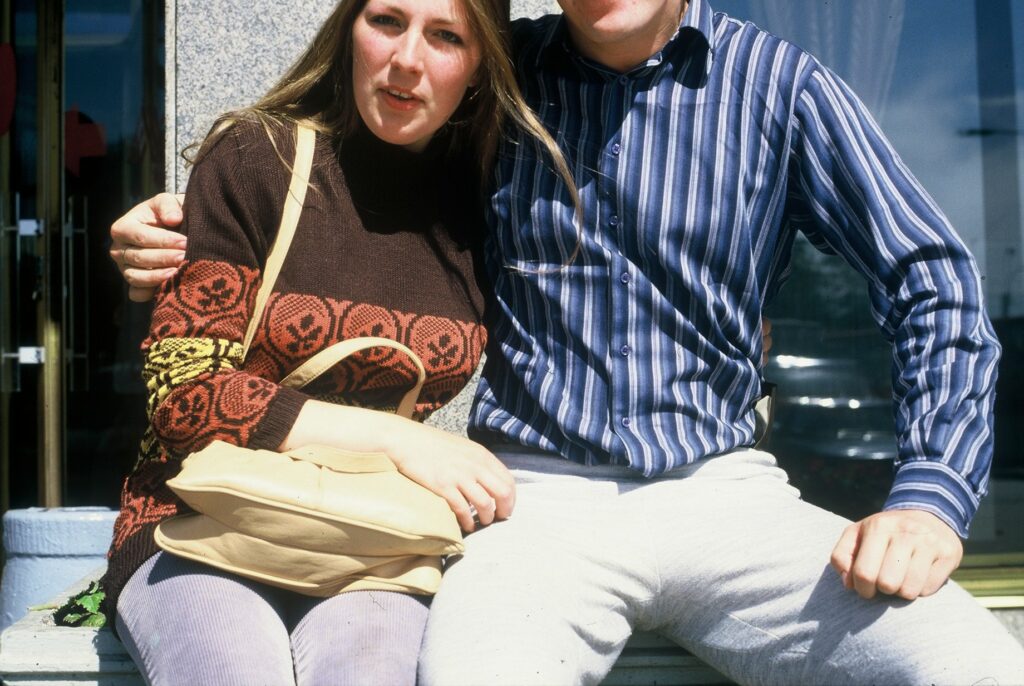

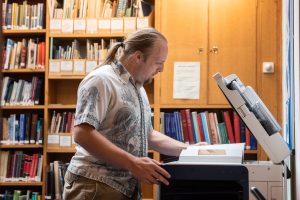

I didn’t routinely take digital photos until after Claire and I got together in 2002 (she had a digital camera, with which the photo above was taken). My first cameraphone – I was a relatively early-adopter – was a Nokia 7650, bought late that same year.

It occurs to me that I take more photos in a typical week nowadays, than I took in a typical year circa 2000.

This got me thinking: what’s the oldest digital photo that exists, of me. So I went digging.

I might not have owned a digital camera in the 1990s, but my dad’s company owned one with which to collect pictures when working on-site. It was a Sony MVC-FD7, a camera most-famous for its quirky use of 3½” floppy disks as media (this was cheap and effective, but meant the camera was about the size and weight of a brick and took about 10 seconds to write each photo from RAM to the disk, during which it couldn’t do anything else).

In Spring 1998, almost 26 years ago, I borrowed it and took, among others, this photo:

I’m confident a picture of me was taken by a Connectix QuickCam (an early webcam) in around 1996, but I can’t imagine it still exists.

So unless you’re about to comment to tell me know you differently and have an older picture of me: that snap of me taking my own photo with a bathroom mirror is the oldest digital photo of me that exists.