Back in 2009, I wrote about Open-Source Shaving, and the journey I’ve taken over the years to arrive at my current preferred

shaving solution: the double-edged traditional safety razor pictured. It’s great: reasonably heavy, just aggressive enough, and far more… manly than anything made of plastic.

It’s so manly, in fact, that merely using it results in a surge of testosterone sufficient to make you grow a bad-ass beard, which somewhat undermines the entire exercise.

Back in 2009, I wrote about Open-Source Shaving, and the journey I’ve taken over the years to arrive at my current preferred

shaving solution: the double-edged traditional safety razor pictured. It’s great: reasonably heavy, just aggressive enough, and far more… manly than anything made of plastic.

It’s so manly, in fact, that merely using it results in a surge of testosterone sufficient to make you grow a bad-ass beard, which somewhat undermines the entire exercise.

That blog post attracted a lot of comments, both on and off the web, and since I wrote it I’ve tried a few other different approaches to shaving, too. Like this:

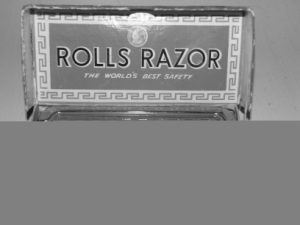

The Rolls Razor

After reading my first Open-Source Shaving post, a friend delivered to me a Rolls Razor that they’d found in a charity shop. I’ll admit that it took me far longer than it ought to have just to open the case, but when I did, I was thoroughly impressed.

The Rolls is a self-contained, self-sharpening, safety razor, in a sleek portable case. That’s right: it’s a safety razor… that you can reuse like a straight razor! The last one was made in the 1950s, and I’m pretty sure that mine was made in the mid-1940s, but these things were built to last and the one I was given is still in perfect working order despite being older than my parents (who aren’t).

The case can be opened from either side, and under each “lid” is a different surface: a sharpening stone under one and a leather stop under the other. A lever arm mechanism folds down and attaches to the blade, such that moving the lever backwards and forwards sharpens or strops the blade, depending on whichever side you didn’t remove. It’s tucked into the most remarkably small space, and yet still manages a wonderful feat of trickery: as is correct, the blade grinds forwards when it’s against the stone, and draws backwards when it’s against the strop – a remarkable feat of engineering.

When you’re ready to use it, a clip-on handle (which also fits neatly inside the case) is attached to the blade. The fit is snug, and it’s not always easy to push the blade into position, but that’s far better I suppose than a loose and wobbly blade.

The shave is raw and basic. Despite the fact that it looks no more-sophisticated than a straight edge, it’s almost as easy to shave with as a disposable-blade safety razor. The blade feels a little bit narrow, and it takes more strokes than would be ideal, but it’s perfectly usable. On the scale of things, it’s certainly preferable to an electric shaver or a plastic disposable razor, but it’s not quite as good as a cartridge razor or – still my personal favourite – a double-edged safety razor with disposable blades.

Nonetheless, it’s a wonderful piece of engineering and I’m proud to own one. There’s a great guru-page about the Rolls Razor, if you’re interested to learn more.

The Shavette

Here’s where things get scary.

I’ve always wanted to try a straight edge – you know, a proper razor blade: a strip of metal sharpened on one side. I’ve been told that it’s an incredibly close shave, a wonderfully tactile experience, and a challenge to dexterity to challenge even the handiest of men. But there’s an overhead: you need a strop, and a sharpening stone, and there’s a whole suite of skills that you need to learn about care and maintenance before you even get close to putting a blade near a face.

A shavette – or “injector razor” – is a simpler alternative. It’s functionally a straight razor, but instead of having a blade it has a pair of closely aligned grips and a clip to hold them in place. You take a traditional double-edged razor blade (which I have about a million of anyway), snap it – carefully! – in half, and insert one half into the grips, then clip it into place. Ta-da: you have a piece of metal shaped like a straight razor, but holding a disposable sharp edge.

The challenge is learning how to use it. It turns out that there’s a reason that you have a barber do this for you: it’s actually really quite hard!

Finding a suitable angle of attack isn’t hard so long as you’re used to using a safety razor already: that same 30° or so angle that words for a safety works when you don’t have a guard in place too. You’ve got to remember to maintain the angle, of course, because the tactile feedback is subtler and more gentle, and it’s easy to slip up. It’s also challenging because – unlike a real straight edge – razor blades have corners, and those corners can catch if you’re not taking care in more-rugged terrain such as around the jawline.

The grip used for a straight razor looks unwieldy, but it’s actually quite comfortable and gives a great deal of control over the motion of the blade. It’s possible to perform strokes that just aren’t feasible with any other kind of shaving equipment, like scything, where a rotation is applied such that the tip of the blade moves further than the end closest to your fingers. It’s challenging, but effective.

But the biggest difficulty with shaving yourself with a straight razor or shavette, for me, has to be that you have to be ambidextrous! I’d read this fact online even before I got my razor, but I’d somehow glossed over it: somehow in my mind I thought that I’d have no problem with just using my right hand. But the first time I tried to shave with a shavette, I realised my mistake: if you try to shave the left-hand side of your face with your right hand… your arm is in front of your eyes! The angle is just about achievable, but without being able to see the mirror you’re quickly going to find yourself in pain.

I got the hang of working left-handed, eventually, but it was a struggle. And while the shave isn’t much cleaner than a safety razor, it is possible to get a great deal of control. I still use my shavette from time to time, particularly if I want to get a very sharp, tidy finish around the edges of my beard or to straighten my mustache, but from a standpoint of speed and convenience alone, my safety razor is still the first thing I reach for.

The Glass Hone

I was recently given a glass hone: a small piece of slightly curved glass that can be used to hone (align) plain old razor blades. The theory is sound – it’s well known that blades require honing far sooner than they actually require sharpening. It’s not possible to strop a double-edged razor blade, but if this mechanism works then it would provide a means to dramatically extend the lifespan of each blade.

I’ve not used it yet: I’m naturally skeptical of claims of such a magnitude, and I’d like to put together a good double-blind test to see if it actually works as well as it should. I’m thinking I’ll run down a pair of blades, store them, label them, and have somebody else hone one (of their choice) without telling me which. I’ll then try to re-shave with both, try to identify the honed one, and then re-run the whole experiment a few more times before asking my assistant to identify which blades were the honed ones.

Maybe I take these things too seriously.

In any case, I can’t report back to you on how useful such a tool is until I actually get the chance to do so, and as I don’t bother to shave every day, it’d take me a while to get any results. Perhaps others would like to volunteer to participate in my experiment, too? Is there anybody out there who shaves with a double-edged safety razor who’s willing to buy one of these things and provide feedback? We could even have our assistants liaise with one another behind our backs and agree not to hone either blade for one or the other of us, to act as a control group…

Okay: way too seriously.