[disclaimer: this post appears just days after some friends of mine announce their pregnancy; this is a complete coincidence (this post was written and scheduled some time ago) and of course I’m delighted for the new parents-to-be]

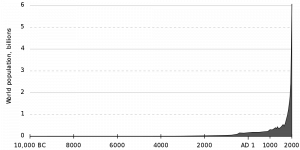

In October, the world population is expected to reach seven billion. Seven fucking billion. I remember being a child and the media reports around the time that we hit five billion: that was in the late 1980s. When my parents were growing up, we hadn’t even hit three billion. For the first nine or ten thousand years of human civilisation between the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution, the world population was consistently below a billion. Let’s visualise that for a moment:

How big is our island?

Am I the only one who gets really bothered by graphs that look like this? Does it not cause alarm?

We have runaway population growth and finite natural resources. Those two things can’t coexist together forever. Let’s have a look at another graph:

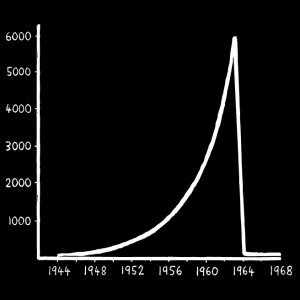

This one is taken from a wonderful comic called St. Matthew Island, about the real island. It charts the population explosion of a herd of reindeer introduced to the island in the 1940s and then left to their own devices in a safe and predator-free environment. Their population ballooned until they were consuming all of their available resources. As it continued to expand, a tipping point was reached, and catastrophe struck: without sufficient food, mass starvation set in and the population crashed down from about 6,000 to only 43. By the 1980s, even these few had died out.

There are now no reindeer on St. Matthew Island. And it looks like this 40-year story could serve as a model for the larger, multi-century, world-wide population explosion that humans are having.

Game Theory

Humans are – in theory at least – smart enough to see what’s coming. If we continue to expand in this way, we risk enormous hardship (likely) and possible extinction (perhaps). Yet still the vast majority of us choose to breed, in spite of the overwhelming evidence that this is Not A Good Thing.

But even people smart enough to know better seem to continue to be procreating. And perhaps they’re right to: for most people, there is – for obvious evolutionary reasons – a biological urge to pass on one’s genes to the next generation. During a period of population explosion, the risk that your genetic material will be “drowned out” by the material of those practically unrelated to you. Sure: there might be a complete ecological collapse in 10, 100 or 1000 years… but the best way to ensure that your genes survive it is to put them into as many individuals as possible: surely some of them will make it, right? Just like buying several lottery tickets improves your chances of hitting the jackpot.

On a political level, too, a similar application of game theory applies: if the other countries are going to have more people, then our country needs more people too! Very few countries penalise families for having multiple children (in fact, to the contrary), and those that do don’t do so very effectively. This leads to a “population arms race”, and no nation can afford to fall behind its rivals: it needs a young workforce ready to pay taxes, produce goods, pay for the upkeep of the retired… and conceive yet more children.

The same tired arguments

Mostly, though, I hear the same tired arguments for breeding [PDF]: cultural conditioning and social expectations, a desire to “pass on” a name (needless to say, I have a different idea about names than many people), a xenophobic belief that the world needs “more people like us” but “less like them”, and worry that you might regret it later (curious how few people seem to consider the reverse of this argument).

For me, the genetic problem is easy enough to fix: if your children’s genes are valuable to you because of their direct relationship (50%) to your genes, then presumably your brother’s (50%) and your niece’s (25%) are valuable to you to: more so than that of somebody on the other side of the world? I just draw the boundary in a different place – all of us humans share well over 99% of our DNA with one another anyway: we’re all one big family! We only share a lower percentage with other primates, a lower percentage still with other mammals, and so on (although we still share quite a lot even with plants).

The similarity between you and your children is only marginally more – almost insignificantly so – than the similarity between you and every other human that has ever lived.

If you’re looking for a “family” that carries your genetic material: you’re living in one… with almost seven billion brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles and aunts! If you can expand your thinking to include the non-human animals, too, well: good for you (I can’t quite stretch that far!). But if you’re looking to help your family survive… can you expand that thinking into a loyalty to your species, instead, and make the effort to reduce population growth for the benefit of all of us?

The other argument I frequently see is the “replacement” argument: that it’s ethically okay for a breeding pair of humans to have exactly two children to “replace” them. This argument has (at least) three flaws:

- The replacement is not instantaneous. If a couple, aged 30, have 2 children, and live to age 80, then there are 50 years during which there are four humans taking up space, food, water and energy. The problem is compounded even further when we factor in the fact that life spans continue to increase. If you live longer than your parents, and your children live longer than you, then “replacement” breeding actually results in a continuous increase in total population.

- Even ignoring the above, “replacement” breeding strategies only actually works if they’re universal. Given that many humans will probably continue to engage super-replacement level reproduction, we’re likely to need a huge number of humans to engage in sub-replacement level or no reproduction in order to balance it out.

- It makes the assumption that current population levels represent a sustainable situation. That might or might not be true – various studies peg the maximum capacity for the planet at anywhere between one and a hundred billion individuals, with the majority concluding a value somewhere between four and ten billion. Given the gravity of the situation, I’d rather err on the side of caution.

Child sandwiches

“Do you not like children, then?” I’m sometimes asked, as if this were the only explanation for my notion. And recently, I’ve found a new analogy to help explain myself: children are like bacon sandwiches.

Children are like bacon sandwiches for five major reasons:

- Like most (but not all) people, I like them.

- I’d love to have them some day.

- But I choose not to, principally because it would be ethically wrong.

- I don’t want to prevent others from having them (although I don’t encourage it either), because their freedom is more important than that they agree with me. However, I’d like everybody to carefully consider their actions.

- They taste best when they’re grilled until they’re just barely-crispy. Mmm.

Now of course I’ve only been refraining from bacon sandwiches for a few months: that’s why this is a new analogy to me… but I’ve felt this way about procreation for as long as I can remember.

The reasons are similar, though: I care about other humans (and, to a much lesser degree, about other living things, especially those which are “closer” family), and I’d rather not be responsible, even a little, for the kind of widespread starvation that was doubtless experienced by the reindeer of St. Matthew Island. Given the way that humans will go to war over limited resources and our capacity to cause destruction and suffering, we might even envy the reindeer – who “only” had to starve to death – before we’re done.

Surely this irritating insistence on creating more bloody young people is only half of the problem, though? As you mentioned, two people producing two more people isn’t a completely fair deal as there’s that large chunk of time between the new ones being born and the old ones popping their clogs and at least a chunk of the problem is that that gap’s getting larger, owing to our insistence on feeding and heating people longer and longer after they would previously have done the decent thing and helped to keep the population down by way of their local crematorium.

In this context, the idea of continuously nudging up the age of retirement seems rather sound: work the buggers into (and, if at all possible, under) the ground to clear some space for the new’uns, although I can see myself becoming ever more disillusioned with that one as my own years advance. But short of some kind of Logan’s Run-esque age-control policy (or my own favoured option to alleviate both overcrowding and food shortage: Soylent Retirement Homes), that annoying habit of ours of managing to lead increasingly long and healthy lives seems just as troublesome as some people’s obsession with popping sprogs into the world every nine months or so.

Well said. Personally, I care more about the wellbeing of current, existing humans than I do about hypothetical future ones, though, so given the choice between reducing fertility rates and reducing life expectancy for similar quality-of-life results, I’d choose the former.

We almost-certainly need to keep our population working longer, for economic reasons. And we’re I to get my wish of Far Fewer Babies, that would be even more true than it is today. With no new people to pay our pensions and healthcare needs, we’d doubtless have to work far later into life. And a dramatically-shrinking fertility-rate-fed population will produce other problems, too, like an insufficiency of (young, working) doctors to care for the (multitudinous, dying) old people. But the sooner we’re able to turn around our population explosion, the slower a population decline we can tolerate without “going reindeer” on our island.

Thanks for the comment.

This is one of those problems which I have declared ‘too hard’, so I don’t worry about it. As far as the meat thing goes, even though I’m becoming less and less veggie I still try and limit my intake, but I just can’t handle this one.

The small amount of thinking I’ve been able to do about it has lead me to try and donate money to charities which reduce the infant mortality rate in developing countries, because I think that might help. But really, in my heart of hearts, I think we’re fucked. And I wanna have babies.

I’m glad that you’re conscientious about the impact of your diet, even though you’re not 100% vegetarian these days. If everybody in the Western world ate the way that you did, we could all be a lot better off.

I suspect that you’re right when you say that we’re fucked. I anticipate that we’ll go the way of the reindeer, too, with a cataclysmic population collapse. But even if it’s inevitable, that doesn’t make it “right” to me to participate in bringing it on, and honestly – if I were the kind of person to care about having genetic offspring, I’d be even more concerned about what kind of world I was setting up for my ((great-)grand)children. But that’s just me.

And yeah; as you and Andy have indicated, people do “just want to” create babies. And given that, I just hope that they’ll be mindful of the impact of that decision, and will consider having fewer children than they might if resources were not (becoming) a critical issue. For all of us. Rather than “one is okay, but definitely stop at two,” I think that we should be saying “none is okay, but definitely stop at one”.

But yeah: it’s hard to fully grasp what one’s individual impact is in destroying the world. It’s easier if you’re a supervillain with a giant death laser: you can actually see your impact in real-time. Also – you have a cool giant death laser.

From my limited experience of places like Africa (certainly Nigeria and to a lesser extent Kenya and Tanzania) people are expected to have lots of kids there. Think 12 or so. The problem with reducing infant mortality is that those 12 in the past would have become approximately 2 breeding adults, but now are becoming 12 breeding adults.

I don’t think the modern Western “2 in, 2 out” way of having kids is the problem, it’s the parts of the world where education is still low and healthcare has rocketed that is causing significant strains on resources.

It wasn’t that different here in the UK all that long ago too. I’m currently transcribing some stories my Grandmother wrote before she died. She mentioned that her father was one of 7, her mother one of 12. She was one of 4 and she had 4 kids herself. She lost a brother, so it was only really my parents’ generation where children started surviving through to adulthood.

Saying “don’t breed” won’t solve the problem. “Breed less” would be a far more realistic proposition. I’d love to know what’s caused the rates of births to drop across the UK and Europe, and see if we can replicate that elsewhere instead.

Yes yes yes! Breed less is the ideal, in my mind. I can’t trust others to do that, so I’m compensating for about one of them by going that little bit further.

Same’s true with my abstaining from meat, as a partial reason. Ideally, we’d all eat very little, but as that’s not the case (by a long, long way), I’m trying to help to make up for the shortfall, among other things.

“2 in, 2 out” is a problem if life expectancies continue to increase and/or if we have too many people already, both of which may be true.

But yes: “breed less” should be the message, but how we make it stick I don’t know.

Yeah, well, my theory (completely unfounded in any kind of fact or knowledge) is that one of the reasons for high birthrates is high infant mortality. There are probably lots and lots of other factors, but that one seems like a big deal: more babies is insurance against losing some of them.

Some backup for this theory, perhaps: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sovereign_states_and_dependent_territories_by_birth_rate

tl; dr

Maters gon’ mate.

I think all the very empirical, rational arguments you’ve gone through in this post probably don’t enter the heads of most people when they decide to have children. People have children because we’re hard-wired to want to have children. It doesn’t mean it’s not a bad idea in the wider context, but people don’t think about that.

So any move to discourage people from having kids is doomed. Think about everything you’re asking (not quite the right word, I know) people to give up throughout the whole course of their lives just to drop the population one miniscule notch on a graph…

The population will decline one day because something awful happens to make it decline. Some sort of human society may well emerge from the ashes in diminished numbers. Those people will probably be no more or less happy on average than anyone is now. It doesn’t, in the end, matter.

Plus longevity is a very significant contributor to the rising population as well, you can’t just look at birth rates. Thankfully the current government’s plans to comprehensively fuck up the NHS should go some way to addressing that.

Some way to addressing the problem in the UK, perhaps. Average life expectancy worldwide can be expected to continue to increase for several decades, yet, while infant mortality continues to decrease. We’re all fucked.

I was about to say a lot of this – Dan, you are asking people to live a totally different life than the one they imagined for themselves, the one their parents had, to make a tiny impact. The number of people willing to make this choice are so small that it will have an insignificant effect. Why make yourself unhappy when you know you can’t save anything by doing so? To take the moral high ground?

This is another attempt to make individuals feel and act responsible for global problems. That basically never works. Changing habits forcibly via legislation works (c.f. rainforest protection, recycling). Occasionally, asking a celebrity chef to get behind a cause does something, as with Chicken Out and Fish Fight, but you’re gonna have to work on a good slogan. “Kids – they just get in the way, don’t they?” is my best offering.

In short, you have to do what China tried to do to get anywhere, in combination with a Soylent Retirement Home (thanks, Adam). Most people would be opposed to that level of control from on high, so we’re doomed.

No, I’m not asking people to live in any particular way, although I wish that they would. It’s more-important to me that people have the personal liberties that allow them to make their (stupid, wrong, immoral) choices than that they make my (smart, correct, moral) choices.

But I would like people to think before they breed. And that’s what this blog post aims to help with: helping to encourage people to think first, procreate later, rather than the other more-popular alternative.

You’ve not addressed any of my points, though — why would someone choose not to breed (for population reasons) in the face of overwhelming odds against it making a difference to population? In what sense is it the right thing to do?

Why would anybody choose not to murder people in the face of overwhelming odds against it making a difference to the murder rate?

I admire people with quixotic attitudes.

Knowing that it probably won’t work shouldn’t stop you from trying.

Murder, even the idea of it, makes you feel pretty awful. A sort of vague “should we have done this, what about the far future” can easily be erased by a giggling child, I suspect.

I just don’t think this is the best way (even assuming there *is* a way) to achieve these aims, as we discussed over GTalk. I won’t bore everyone else with it though, thread’s too deep already!

A persuasive (/nagging) wife can have a more powerful influence on decision making than any rational argument about global resources.

As you allude to in your post, genetically we’re basically ‘just’ animals. This means that we probably have a reindeer-like instinct to just keep on reproducing while resources allow. Stating that resources are critical won’t stop that. Only wars and famine and other nasties will. There’s nothing significant any of us can do so there’s probably no point worrying about.

If I remember my A-Level geography correctly Malthus talked of positive and negative checks to stop reindeer-like catastrophes occuring. Some of these that can be seen today could be famines in Africa, wars in the Middle East (positive checks) that kill people and things like people marrying later, economic turmoil, and the ‘acceptability’ (sorry, I know that’s probably the wrong word) of homosexual lifestyles (negative checks) that lead to fewer births. These negative checks are all more common in richer or what are considered (another horrible word) more civilised countries so it could be a case of: as all countries become richer and more liberal the birth rates will fall and the impact on resources will be less.

I appreciate that that’s very simplistic, will take a long time, and does not consider that we’ll all live longer, but at least it’s not neccessarily all doom and gloom.

I think there is an unpleasant but obvious solution, which you have eluded to in your comment “children are like bacon sandwiches”

Eat children

Must I reference http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Modest_Proposal ?

Problem? Solved!

:D

That would probably work for a while, but then we’d start getting prion based diseases and then we’re all screwed. Again.

Maybe having children is kind of like recycling.

Sure, you could just have a new one and it’s probably less hassle, but it’s environmentally and (probably) morally better to get a second-hand one somebody else doesn’t want.

Like cars. Except the second-hand ones don’t produce more pollution.

Adoption is also an option. Albiet, not for everyone. I don’t know enough about the adoption process in the UK to comment on it’s ease or it’s difficulty, but if people want kids and are considering the ethical implications of it, adoption may be a good alternative.

I’m not birthing any kids, not because I don’t want them, but because of this reason and a few other philosophical and physical reasons. I’m hopefully going to either have a partner who has kids with someone else or foster/adopt children.

I know plenty about it, being adopted myself, and it’s much much harder than just popping out a sprog. In terms of forms and such, not physical pain, obviously! If all else were equal this would be my preference. It’s the obvious solution to most of the arguments. Unfortunately it takes about 2 years to get to the point of being on the list, and there are a whole lot of things that can screw you over that don’t seem to get social services called for “real” parents. I’d like to see parenting rules brought closer to adoption rules and vice versa.

I figured as much. And I think some people like myself, who are gender variant and interested in non-monogamy aren’t likely to be considered “fit” parents, even within the UK where it’s relatively liberal.

I’m hoping maybe fostering is a bit easier? We’ll see what happens. I think I might have to just be a constant baby sitter or god-parent.

Adoption agencies are getting far more liberal. I’m pretty sure that those which receive any state funding are no longer allowed to discriminate on anything in the various Acts that disallow discrimination, so sexuality and gender terminology are protected. Nonmonogamy could be argued as an “unstable environment”, sadly, even in the presence of overwhelming contrary evidence in any individual case, so that could well count against you for now, assuming you were honest and open about it.

That said, I’m aware of a nonmonogamous gay couple who successfully adopted despite the agency being in full knowledge of this, so it’s not impossible. If the time comes: good luck!

It took until 2005 for unmarried couples (whatever their sexuality) to be able to adopt jointly; I think it’ll be a while before you can have more than 2 legal guardians, if that was what was wanted. Otherwise, it’s a lottery of who your assessor is as to whether they deem your situation conducive to a happy childhood. Yes, good luck!

I think the reindeer scenario is already happening in some parts of the world (horn of Africa?). And in other parts, birth rates are dropping enough to endanger smooth social functioning and to prompt government concern (Italy? Germany?). But we can’t just redistribute people because this is, in fact, a very big, diverse, and unequal island we’re on.

But the real reason I posted is your long discussion of people wanting to pass on a name or a genetic heritage, even those you call smart enough to “know better”. I think these are straw targets. Many (most?) people have children for love, to experience those incredible joyous highs that children bring (along with the grinding hard work, of course). You don’t use the word “love” anywhere in your blog post (apart from saying you’d “love” to have kids one day, which is slightly different use of the word, I think). I know it’s deeply unfashionable to talk about love, but I think it’s a central concept here with regards to what you’re arguing. To ask people not to love is profoundly unethical: freedom to love is, for some people, the only freedom they will ever have.

It doesn’t solve our population problems, of course, but I just wanted to signal that there is far more at stake here than biological urges. Perhaps you think that love for a child is a biological urge and my counter-argument therefore holds no water. But I would ask you not to be too quick to come to that conclusion. There are of course biological urges involved, but love is something of a different order and if we can put aside our fear of sentimentality to talk about it, we might open up new facets of these important debates.

Thanks for your comment, stranger Kim.

That’s an interesting answer. But as far as I see it, I don’t know how I can be expected to feel love for somebody who hasn’t even been conceived yet! Love certainly goes a long way to explaining why people keep children, but for me at least it doesn’t explain why they have them in the first place. But perhaps I’m missing something.

Please do go on.

i mean wanting the experience of love: that almost mythical love that people have written rapturous poetry about for centuries. i think this is particularly acute for women: you think, I want that. I want to know that love. and it’s not a disappointment when it comes. it’s stepping off the sandbar into the ocean: deep and thrilling and terrifying all at once. so the desire to experience that love inspires people to have children, to know the outer limits of human experience. it’s very hard to talk about without sounding insane or sentimental, but that is my project: to put love back on the agenda as a concept, rather than denying it’s there because it seems too irrational a thing to talk about.

This, too, is a reason in favour of breeding over adoption. A potential person growing inside you seems by turns alienesque and magical. Breastfeeding is something you can only do if you have been pregnant. I want these experiences in spite of, perhaps even because of, having been adopted myself.

Surely intestinal parasites should get love too?

Actually, lactation can be induced in humans by a variety of methods. It is not strictly necessary to become pregnant to be able to experience breastfeeding.

Well, https://secure.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/wiki/Erotic_lactation there’s something I never wanted to see…

Ultimately, is it not a greater issue what those seven billion people consume? Is it not how we divide up resources rather than how many people they’re divided between?

Living more modestly and simply makes people happier (references available on request), it’s the idea that our world can support billions of people who all have the right to a car, computer, and daily portions of meat which will fuck us. Having children gives (or should give) parents more pleasure and fulfilment than any of the wasteful tat humans consume. We could plan for an increase in population if people were a considerable measure less selfish. Obviously even this would only be true up to a point…

Going off topic a little, a thought has occured to me in light of this post, and your previous post on vegetarianism…

I’ve previously heard you use the precise opposite argument – re: the vanishingly small difference an individual changing their behaviour can make – against both the ‘moral obligation’ (for want of a better phrase) to vote in elections, and against the value of individuals, rather than society as a whole, attempting to address climate change.

I’d be interested to hear if you’ve changed your views on those things in the few years it’s been since we last discussed them.

Sorry about the delay in responding to this. I kept thinking up long answers which would be best used as blog posts in their own right. But regardless, the “short answer” would be this:

My opinion has not changed on the futility of individual action in order to elicit large changes, in many popular activities (e.g. politics, much vegetarianism, etc.). However, it’s important to understand that there’s a difference between attempting to change the world and what I’m doing (both in not-having-children, and in not-eating-meat alike), although there is some overlap:

In both cases, I’m engaging in behaviour that I hope others would emulate: I’m of the opinion that both of these actions are things that are better for the world and humanity in general, at a value that pays-off over the cost.

However, this in itself is not my primary motivation in either case: I don’t expect nor plan to change the world. In both cases, I’m acting as I am because it wouldn’t be morally right for me to do otherwise. It’s my personal ethics that are my motivation, not a drive to change anything.

To take an alternative example: I try to be a conscientious cyclist – I don’t hog lanes, I let cars out where it’ll be difficult for them to pass me otherwise (I am, after all, a slow vehicle – relatively speaking), and I try to avoid acting in a way that’s inconvenient or dangerous to pedestrians. It’d be easier, sometimes, to be a dick of a cyclist, but it wouldn’t be right. Similarly, I wish that all cyclists were more conscientious: but I don’t expect to change the average by my efforts, not by any meaningful amount. However, I persist in doing what I feel is the right thing simply because it’s right.

I can argue for the (objective, generally) reasons it’s right and I can follow that advice myself, but I can’t force anybody else to do it, although I hope that they will. But the more important part of the process to me is that I don’t feel like I’m part of the problem any more than I have to.

It’s a personal battle inspired by a universal crusade, but the fact that it’s not changing the world does not change the fact that it’s a personal battle.

Voting in elections is an entirely different situation, for me: my vote taken alone makes no significant difference to the result, but I don’t feel that it’s “wrong” to not-vote. Although as you probably know: in my case I tend to spoil a ballot at general elections anyway.

Oh, and you’re totally right about the benefits of simple living. I wish I were better at it.

http://www.theonion.com/articles/civilization-to-hold-off-on-having-any-more-kids-f,26232/