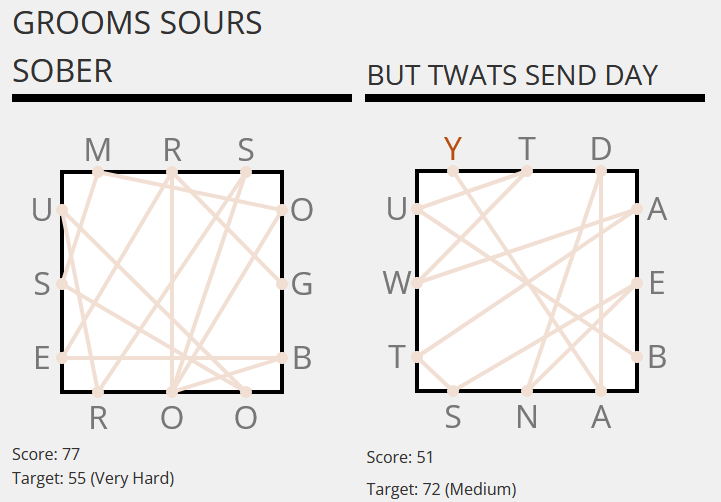

I’ve been enjoying playing Chain Words, from eclectech, intermittently, since it came out in November (when I complained that the word ‘TOSSPOT’ was rejected; I don’t know if this obvious omission has yet been corrected). If you’ve not given it a go yet, and you like a word game that’s “a bit different”, you should try it!

Tag: words

Note #27692

Can it perhaps be time that we stop saying “ethical non-monogamy”?

Nobody feels the need to say “ethical monogamy”; monogamous folks are given the benefit of the doubt and assumed to be practicing a relationship ethically.

I feel like polyamory, open relationships, relationship anarchy and other forms of non-monogamy are now sufficiently accessible to popular culture that we can drop the word “ethical” and still be understood. (Ideally we do so before it starts to look like virtue-labelling.)

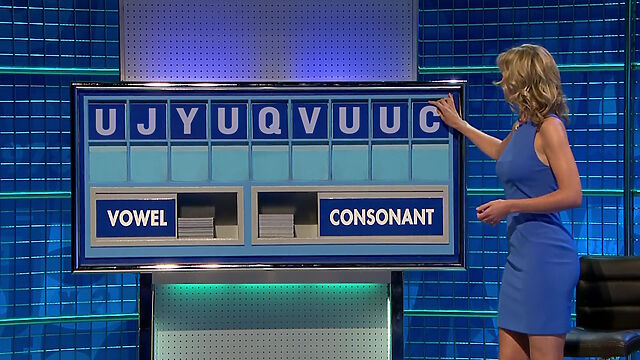

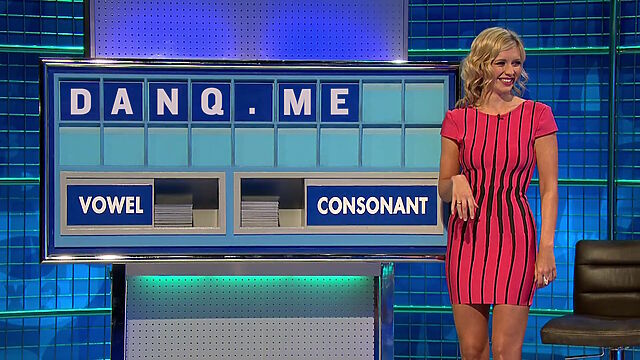

Impossible Countdown

Or: Sometimes You Don’t Need a Computer, Just a Brain

I was watching an episode of 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown the other night1 and I was wondering: what’s the hardest hand you can be dealt in a Countdown letters game?

Sometimes it’s possible to get fixated on a particular way of solving a problem, without having yet fully thought-through it. That’s what happened to me, because the first thing I did was start to write a computer program to solve this question. The program, I figured, would permute through all of the legitimate permutations of letters that could be drawn in a game of Countdown, and determine how many words and of what length could be derived from them2. It’d repeat in this fashion, at any given point retaining the worst possible hands (both in terms of number of words and best possible score).

When the program completed (or, if I got bored of waiting, when I stopped it) it’d be showing the worst-found deals both in terms of lowest-scoring-best-word and fewest-possible-words. Easy.

Here’s how far I got with that program before I changed techniques. Maybe you’ll see why:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby WORDLIST = File.readlines('dictionary.txt').map(&:strip) # https://github.com/jes/cntdn/blob/master/dictionary LETTER_FREQUENCIES = { # http://www.thecountdownpage.com/letters.htm vowels: { A: 15, E: 21, I: 13, O: 13, U: 5, }, consonants: { B: 2, C: 3, D: 6, F: 2, G: 3, H: 2, J: 1, K: 1, L: 5, M: 4, N: 8, P: 4, Q: 1, R: 9, S: 9, T: 9, V: 1, W: 1, X: 1, Y: 1, Z: 1, } } ALLOWED_HANDS = [ # https://wiki.apterous.org/Letters_game { vowels: 3, consonants: 6 }, { vowels: 4, consonants: 5 }, { vowels: 5, consonants: 4 }, ]

At this point in writing out some constants I’d need to define the rules, my brain was already racing ahead to find optimisations.

For example: given that you must choose at least four cards from the consonants deck, you’re allowed no more than five vowels… but no individual vowel appears in the vowel deck fewer than five times, so my program actually had free-choice of the vowels.

Knowing that3, I figured that there must exist Countdown deals that contain no valid words, and that finding one of those would be easier than writing a program to permute through all viable options. My head’s full of useful heuristics about English words, after all, which leads to rules like:

- None of the vowels can be I or A, because they’re words in their own right.

- Five letter Us is a strong starting point, because it’s very rarely used in two-letter words (and this set of tiles is likely to be hard enough that three-letter words are already an impossibility).

- This eliminates the consonants M (mu, um: the Greek letter and the “I’m thinking” sound), N (nu, un-: the Greek letter and the inverting prefix), H (uh: another sound for when you’re thinking or hesitating), P (up: the direction of ascension), R (ur-: the prefix for “original”), S (us: the first-person-plural pronoun), and X (xu: the unit of currency). So as long as we can find four consonants within the allowable deck letter frequency that aren’t those five… we’re sorted.

I enjoyed getting “Q” into my proposed letter set. I like to image a competitor, having already drawn two “U”s, a “J”, and a Y”, being briefly happy to draw a “Q” and already thinking about all those “QU-” words that they’re excited to be able to use… before discovering that there aren’t any of them and, indeed, aren’t actually any words at all.

Even up to the last letter they were probably hoping for some consonant that could make it work. A K (juku), maybe?

But the moral of the story is: you don’t always have to use a computer. Sometimes all you need is a brain and a few minutes while you eat your breakfast on a slow Sunday morning, and that’s plenty sufficient.

Update: As soon as I published this, I spotted my mistake. A “yuzu” is a kind of East Asian plum, but it didn’t show up in this countdown solver! So my impossible deal isn’t quite so impossible after all. Perhaps U J Y U Q V U U C would be a better “impossible” set of tiles, where that “C” makes it briefly look like there might be a word in there, even if it’s just a three or four-letter one… but there isn’t. Or is there…?

Footnotes

1 It boggles my mind to realise that show’s managed 28 seasons, now. Sure, I know that Countdown has managed something approaching 9,000 episodes by now, but Cats Does Countdown was always supposed to be a silly one-off, not a show in it’s own right. Anyway: it’s somehow better than both 8 Out Of 10 Cats and Countdown, and if you disagree then we can take this outside.

2 Herein lay my first challenge, because it turns out that the letter frequencies and even the rules of Countdown have changed on several occasions, and short of starting a conversation on what might be the world’s nerdiest surviving phpBB installation I couldn’t necessarily determine a completely up-to-date ruleset.

3 And having, y’know, a modest knowledge of the English language

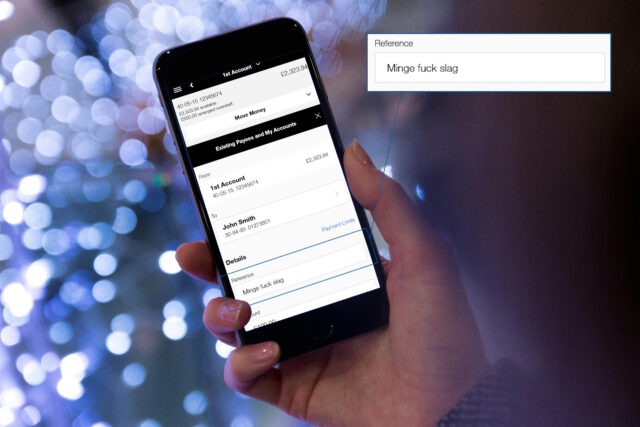

The 55 Words you Can’t Say in Faster Payments

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Step aside, George Carlin! Sam Easterby-Smith – who works at The Co-Operative Bank – wants to share with the world the 55 words you can’t say in a UK faster payments reference (assuming your bank follows the regulator‘s recommendations):

…

So you know, this list is provided by Pay.uk the uk’s payment systems regulator. This is their idea of how to protect people from abusive content sent via the payment system.

Of course (a) all abusive messages must contain one of these English words, spelled correctly and (b) people are not in any way creative.

We’ve called it out and they are making us do it anyway.

- bastard

- beef curtains

- bellend

- clunge

- cunt

- dickhead

- fuck

- minge

- motherfucker

- prick

- punani

- pussy

- shit

- twat

- bukkake

- cocksucker

- nonce

- rapey

- skank

- slag

- slut

- wanker

- whore

- fenian

- kufaar

- kafir

- kike

- yid

- batty boy

- bum boy

- faggot

- fudge-packer

- gender bender

- homo

- lesbo

- lezza

- muff diver

- retard

- spastic

- spakka

- spaz

- window licker

- gippo

- gyppo

- golliwog

- nigger

- nigaa

- nig-nog

- paki

- raghead

- sambo

- wog

- blow Job

- clit

- wank

Excellent.

The big takeaway here, for me, is that it’s okay to send you money and call you a “dick head” (so long as I put a space between the words), “fuckface”, or “shitbag”, or talk about a “blowjob” (so long as I don’t put a space between the words).

But if I send you money to pay “for the bastard sword” that you’re selling then that’s a problem.

Magical

For World Book Day (which here in the UK is marked a month earlier than the rest of the world) the kids’ school invited people to come “dressed as a word”.

As usual, the kids and teachers participated along with only around two other adults. But of course I was one of them.

This year, I was “magical”.

[Bloganuary] Magpies are the Best Bird

This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What is your favourite animal?

The common magpie, pica pica.

They’re smart (among the smartest corvids, who are already among the smartest birds).

They’re curious. They’re sociable. And they’re ever so pretty.

They’re common enough that you can see them pretty-much anywhere.

They steal things. They solve puzzles. They’re just awesome.

Also, did you know where their name comes from? It’s really cool:

- In Medieval Latin, they’re called pica. It probably comes from Greek kitta, meaning “false appetite” and possibly related to the birds’ propensity for theft, and/or from a presumed PIE1 root meaning “pointed” and referring to its beak shape.

- In Old French, this became pie. They’re still called la pie in French today. Old English took this and also used pie.

- By the 17th century, there came a fashion in English slang to give birds common names.

- Sometimes the common name died out, such as with Old English wrenna which became wren and was extended to Jenny wren, which you’ll still hear nowadays but mostly people just say wren.

- Sometimes the original name disappeared, like with Old English ruddock2 which became redbreast and was extended to Robin redbreast from which we get the modern name robin (although again, you’ll still sometimes hear robin reabreast).

- Magpie, though, retains both parts!3 Mag in this case is short for Margaret, a name historically associated with idle chatter4. So we get pica > pie > Maggie pie > Mag pie > magpie! Amazing!

I probably have a soft spot for animals with distinct black-and-white colouration – other favourite animals might include the plains zebra, European badger, black-and-white ruffed lemur, Malayan tapir, Holstein cattle, Atlantic puffin… – but the magpie’s the best of them. It hits the sweet spot in all those characteristics listed above, and it’s just a wonderful year-around presence in my part of the world.

Footnotes

1 It’s somewhat confusing writing about the PIE roots of the word pie…

2 Ruddock shares a root with “ruddy”, which is frankly a better description of the colour of a robin’s breast than “red”.

3 Another example of a bird which gained a common name and retained both that and its previous name is the jackdaw.

4 Reflective, perhaps, of the long bursts of “kcha-kcha-kcha-kcha-kcha-” chattering sounds magpies make to assert themselves. The RSPB have a great recording if you don’t know what I’m talking about – you’ll recognise the sound when you hear it! – but they also make a load of other vocalisations in the wild and can even learn to imitate human speech!

Woodward Draw

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

- Explore the set of 4 letter words

- Either change one letter of the previous word

- Or rearrange all the letters of the previous word

- Find all 105 picture words!

Woodward Draw by Daniel Linssen is the kind of game that my inner Scrabble player both loves and hates. I’ve been playing on and off for the last three days to complete it, and it’s been great. While not perfectly polished1 and with a few rough edges2, it’s still a great example of what one developer can do with a little time.

It deserves a hat tip of respect, but I hope you’ll give it more than that by going and playing it (it’s free, and you can play online or download a copy3). I should probably check out their other games!

Footnotes

1 At one point the background colour, in order to match a picture word, changed to almost the same colour as the text of the three words to find!

2 The tutorial-like beginning is a bit confusing until you realise that you have to play the turn you’re told to, to begin with, for example.

3 Downloadable version is Windows only.

That Moment When You Forget Somebody’s Dead

Is there a name for that experience when you forget for a moment that somebody’s dead?

For a year or so after my dad’s death 11 years ago I’d routinely have that moment: when I’d go “I should tell my dad about this!”, followed immediately by an “Oh… no, I can’t, can I?”. Then, of course, it got rarer. It happened in 2017, but I don’t know if it happened again after that – maybe once? – until last week.

I wonder if subconsciously I was aware that the anniversary of his death – “Dead Dad Day”, as my sisters and I call it – was coming up? In any case, when I found myself on Cairn Gorm on a family trip and snapped a photo from near the summit, I had a moment where I thought “I should send this picture to my dad”, before once again remembering that nope, that wasn’t possible.

Strange that this can still happen, over a decade on. If there’s a name for the phenomenon, I’d love to know it.

Note #20517

Was a 10th century speaker of Old Saxon a “Saxophone”? 🤔

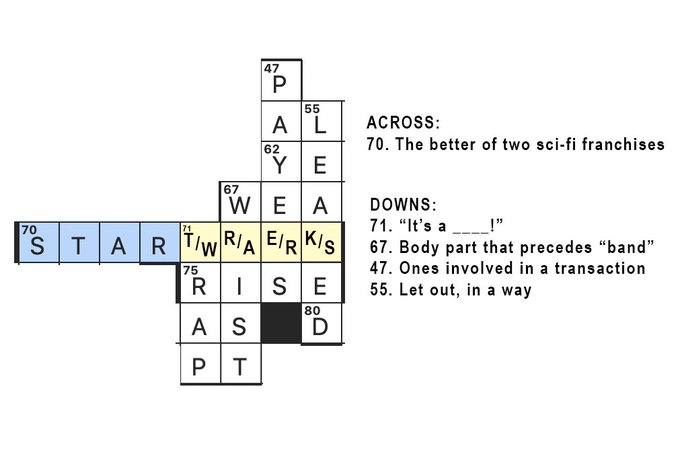

STAR T/W R/A E/R K/S

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Fun little trick in the Sunday New York Times crossword yesterday: the central theme clue was “The better of two sci-fi franchises”, and regardless of whether you put Star Wars or Star Trek, the crossing clues worked

This is a (snippet of an) excellent New York Times crossword puzzle, but the true genius of it in my mind is that 71 down can be answered using iconic Star Wars line “It’s a trap!” only if the player puts Star Trek, rather than Star Wars, as the answer to 70 across (“The better of two sci-fi franchises”). If they answer with Star Wars, they instead must answer “It’s a wrap!”.

Matt goes on to try to make his own which pairs 1954 novel Lord of the Rings against Lord of the Flies, which is pretty good but I’m not convinced he can get away with the crosswise “ulne” as a word (contrast e.g. “rise” in the example above).

Of course, neither are quite as clever as the New York Times‘ puzzle on the eve of the 1996 presidential election whose clue “Lead story in tomorrow’s newspaper(!)” could be answered either “Clinton elected” or “Bob Dole elected” and the words crossing each of “Clinton” or “Bob Dole” would still fit the clues (despite being modified by only a single letter).

If you’re looking to lose some time, here’s some further reading on so-called “Schrödinger puzzles”, and several more crosswords that achieve the same feat.

Goose-Related Etymologies

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

My favourite thing about geese… is the etymologies of all the phrases relating to geese. There’s so many, and they’re all amazing. I started reading about one, then – silly goose that I am – found another, and another, and another…

For example:

- Barnacle geese are so-called because medieval Europeans believed that they grew out of a kind of barnacle called a goose barnacle, whose shell pattern… kinda, sorta looks like barnacle goose feathers? Barnacle geese breed on remote Arctic islands and so people never saw their chicks, which – coupled with the fact that migration wasn’t understood – lead to a crazy myth that lives on in the species name to this day. Incidentally, this strange belief led to these geese being classified as a fish for the purpose of fasting during Lent, and so permitted. (This from the time period that brought us the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, of course. I’ve written about both previously.)

- Gooseberries may have a similar etymology. Folks have tried to connect it to old Dutch or Germanic words, but inconclusively: given that they appear at the opposite end of the year to some of the migratory birds goose, the same kind of thinking that gave us “barnacle geese” could be seen as an explanation for gooseberries’ name, too. But really: nobody has a clue about this one. Fun fact: the French name for the fruit is groseille à maquereau, literally “mackerel currant”!

- A gaggle is the collective noun for geese, seemingly derived from the sound they make. It’s also been used to describe groups of humans, especially if they’re gossiping (and disproportionately directed towards women). “Gaggle” is only correct when the geese are on the ground, by the way: the collective noun for a group of airborne geese is skein or plump depending on whether they’re in a delta shape or not, respectively. What a fascinating and confusing language we have!

- John Stephen Farmer helps us with a variety of goose-related sexual slang though, because, well, that was his jam. He observes that a goose’s neck was a penis and gooseberries were testicles, goose-grease is vaginal juices. Related: did you ever hear the euphemism for where babies come from “under a gooseberry bush“? It makes a lot more sense when you realise that gooseberry bush was slang for pubic hair.

- An actor whose performance wasn’t up to scratch might describe the experience of being goosed; that is – hissed at by the crowd. Alternatively, goosing can refer to a a pinch on the buttocks possibly in reference to geese pecking humans at about that same height.

- If you have a gander at something you take a good look at it. Some have claimed that this is rhyming slang – “have a look” coming from “gander and duck” – but I don’t buy it. Firstly, why wouldn’t it be “goose and duck” (or “gander and drake“, which doesn’t rhyme with “look” at all). And fake, retroactively-described rhyming roots are very common: so-called mockney rhyming slang! I suspect it’s inspired by the way a goose cranes its neck to peer at something that interests it! (“Crane” as a verb is of course also a bird-inspired word!)

- Goosebumps might appear on your skin when you’re cold or scared, and the name alludes to the appearance of plucked poultry. Many languages use geese, but some use chickens (e.g. French chair de poule, “chicken flesh”). Fun fact: Slavic languages often use anthills as the metaphor for goosebumps, such as Russian мурашки по коже (“anthill skin”). Recently, people talk of tapping into goosebumps if they’re using their fear as a motivator.

- A tailor’s goose is a traditional kind of iron so-named for the shape of its handle.

- The childrens game of duck duck goose is played by declaring somebody to be a “goose” and then running away before they catch you. Chasing – or at risk of being chased by! – geese is common in metaphors: if somebody wouldn’t say boo to a goose they’re timid. A wild goose chase (yet another of the many phrases for which we can possibly thank Shakespeare, although he probably only popularised this one) begins without consideration of where it might end up.

- If those children are like their parents, you might observe that a wild goose never laid a tame egg: that traits are inherited and predetermined.

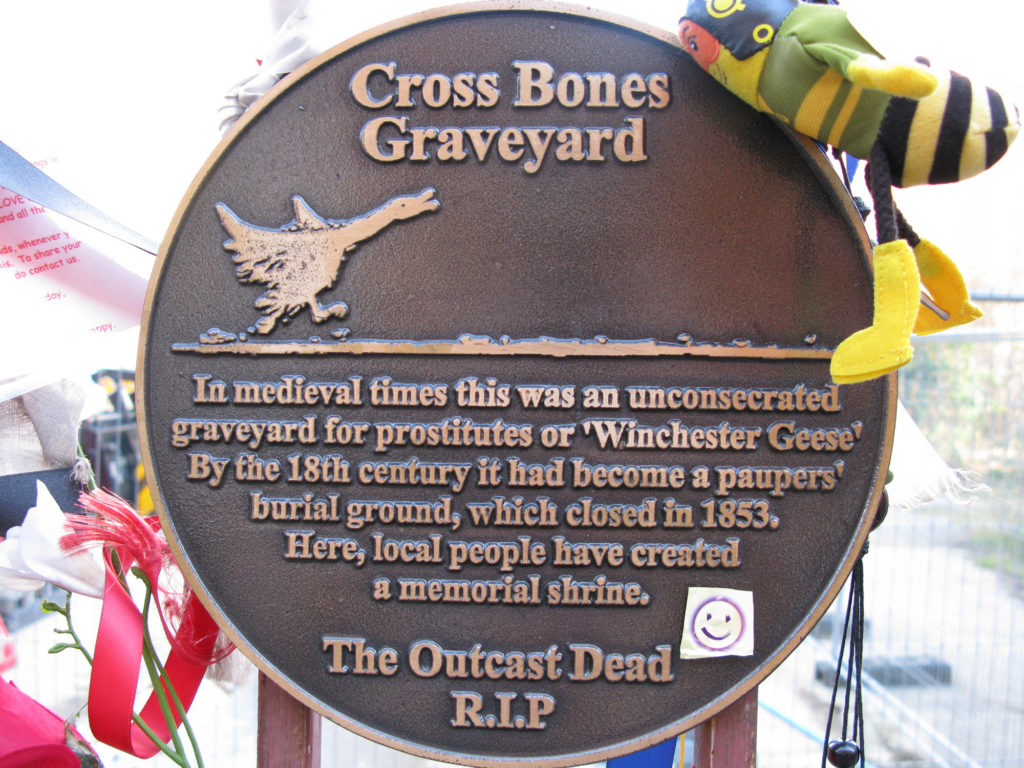

- Until 1889, the area between Blackfriars and Tower Bridge in London – basically everything around Borough tube station up to the river – was considered to be outside the jurisdiction of both London and Surrey, and fell under the authority of the Bishop of Winchester. For a few hundred years it was the go-to place to find a prostitute South of the Thames, because the Bishop would license them to be able to trade there. These prostitutes were known as Winchester geese. As a result, to be bitten by a Winchester goose was to contract a venereal disease, and goosebumps became a slang term for the symptoms of some such diseases.

- Perennial achillea ptarmica is known, among other names, as goose tongue, and I don’t know why. The shape of the plant isn’t particularly similar to that of a goose’s tongue, so I think it might instead relate to the effect of chewing the leaves, which release a spicy oil that might make your tongue feel “pecked”? Goose tongue can also refer to plantago maritima, whose dense rosettes do look a little like goose tongues, I guess. Honestly, I’ve no clue about this one.

- If you’re sailing directly downwind, you might goose-wing your sails, putting the mainsail away from the wind and the jib towards it, for balance and to easily maintain your direction. Of course, a modern triangular-sailed boat usually goes faster broad reach (i.e. at an angle of about 45º to the wind) by enough that it’s faster to zig-zag downwind rather than go directly downwind, but I can see how one might sometimes want to try this anatidaetian maneuver.

Geese make their way all over our vocabulary. If it’s snowing, the old woman is plucking her

goose. If it’s fair to give two people the same thing (and especially if one might consider not doing so on account of their sex), you might say that what’s good

for the goose is good for the gander, which apparently used to use

the word “sauce” instead of “good”. I’ve no idea where the idea of cooking someone’s goose comes from, nor why anybody thinks that a goose step

march might look anything like the way a goose walks waddles.

With apologies to Beverley, whose appreciation of geese (my take, previously) is something else entirely but might well have got me thinking about this in the first instance.

Word Ladder Solver

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

It’s likely that the first word ladder puzzles were created by none other than Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), the talented British mathematician, and author of the Alice’s adventures. According to Carroll, he invented them on Christmas Day in 1877.

A word ladder puzzle consists of two end-cap words, and the goal is to derive a series of chain words that change one word to the other. At each stage, adjacent words on the ladder differ by the substitution of just one letter. Each chain word (or rung of the word ladder), also needs to be a valid word. Below is an example of turning TABLE into CROWN (this time, in nine steps):

TABLE → CABLE → CARLE → CARLS → CARPS → CORPS → COOPS → CROPS → CROWS → CROWN

In another example, it take four steps to turn WARM into COLD.

WARM → WARD → CARD → CORD → COLD

(As each letter of the two words in the last example is different, this is the minimum possible number of moves; each move changes one of the letters).

Word ladders are also sometimes referred to as doublets, word-links, paragrams, laddergrams or word golf.

…

Nice one! Nick Berry does something I’ve often considered doing but never found the time by “solving” word ladders and finding longer chains than might have ever been identified before.

Odd One Out?

While you’re tucking in to your turkey tomorrow and the jokes and puzzles in your crackers are failing to impress, here’s a little riddle to share with your dinner guests:

Which is the odd-one out: gypsies, turkeys, french fries, or the Kings of Leon?

In order to save you from “accidentally” reading too far and spoling the answer for yourself, here’s a picture of a kitten to act as filler:

Want a hint? This is a question about geography. Specifically, it’s a question about assumptions about geography. Have another think: the kittens will wait.

Okay. Let’s have a look at each of the candidates, shall we? And learn a little history as we go along:

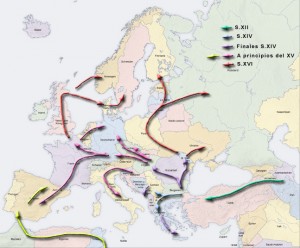

Gypsies

The Romami are an ethnic group of traditionally-nomadic people, originating from Northern India and dispersing across Europe (and further) over the last millenium and a half. They brought with them some interesting anthropological artefacts of their culture, such as aspects of the Indian caste system and languages (it’s through linguistic similarities that we’ve been best-able to trace their multi-generational travels, as written records of their movements are scarce and incomplete), coupled with traditions related to a nomadic life. These traditions include strict rules about hygiene, designed to keep a travelling population free of disease, which helped to keep them safe during the European plagues of the 13th and 14th centuries.

Unfortunately for them, when the native populations of Western European countries saw that these travellers – who already had a reputation as outsiders – seemed to be immune to the diseases that were afflicting the rest of the population, their status in society rapidly degraded, and they were considered to be witches or devil-worshippers. This animosity made people unwilling to trade with them, which forced many of them into criminal activity, which only served to isolate them further. Eventually, here in the UK, laws were passed to attempt to deport them, and these laws help us to see the origins of the term gypsy, which by then had become commonplace.

Consider, for example, the Egyptians Act 1530, which uses the word “Egyptian” to describe these people. The Middle English word for Egypian was gypcian, from which the word gypsy or gipsy was a contraction. The word “gypsy” comes from a mistaken belief by 16th Century Western Europeans that the Romani who were entering their countries had emigrated from Egypt. We’ll get back to that.

Turkeys

When Europeans began to colonise the Americas, from the 15th Century onwards, they discovered an array of new plants and animals previously unseen by European eyes, and this ultimately lead to a dramatic diversification of the diets of Europeans back home. Green beans, cocoa beans, maize (sweetcorn), chillis, marrows, pumpkins, potatoes, tomatoes, buffalo, jaguars, and vanilla pods: things that are so well-understood in Britain now that it’s hard to imagine that there was a time that they were completely alien here.

Still thinking that the Americas could be a part of East Asia, the explorers and colonists didn’t recognise turkeys as being a distinct species, and categorised them as being a kind of guineafowl. They soon realised that they made for pretty good eating, and started sending them back to their home countries. Many of the turkeys sent back to Central Europe arrived via Turkey, and so English-speaking countries started calling them Turkey fowl, eventually just shortened to turkey. In actual fact, most of the turkeys reaching Britain probably came directly to Britain, or possibly via France, Portugal, or Spain, and so the name “turkey” is completely ridiculous.

Fun fact: in Turkey, turkeys are called hindi, which means Indian, because many of the traders importing turkeys were Indians (the French, Polish, Russians, and Ukranians also use words that imply an Indian origin). In Hindi, they’re called peru, after the region and later country of Peru, which also isn’t where they’re from (they’re native only to North America), but the Portugese – who helped to colonise Peru also call them that. And in Scottish Gaelic, they’re called cearc frangach – “French chicken”! The turkey is a seriously georgraphically-confused bird.

French Fries

As I’m sure that everybody knows by now, “French” fries probably originated in either Belgium or in the Spanish Netherlands (now part of Belgium), although some French sources claim an earlier heritage. We don’t know how they were first invented, but the popularly-told tale of Meuse Valley fishing communities making up for not having enough fish by deep-frying pieces of potato, cut into the shape of fish, is almost certainly false: a peasant region would be extremely unlikely to have access to the large quantities of fat required to fry potatoes in this way.

So why do we – with the exception of some confusingly patriotic Americans – call them French fries. It’s hard to say for certain, but based

on when the food became widely-known in the anglophonic world, the most-likely explanation comes from the First World War. When British and, later, American soldier landed in Belgium,

they’ll have had the opportunity to taste these (now culturally-universal) treats for the first time. At that time, though, the official language of the Belgian army (and the

most-popularly spoken language amongst Belgian citizens) was French. The British and American soldiers thus came to call them “French fries”.

The Kings of Leon

For a thousand years the Kingdom of Leon represented a significant part of what would not be considered Spain and/or Portugal, founded by Christian kings who’d recaptured the Northern half of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors during the Reconquista (short version for those whose history lessons didn’t go in this direction: what the crusades were against the Ottomans, the Reconquista was against the Moors). The Kingdom of Leon remained until its power was gradually completely absorbed into that of the Kingdom of Spain. Leon still exists as a historic administrative region in Spain, similar to the counties of the British Isles, and even has its own minority language (the majority language, Spanish, would historically have been known as Castilian – the traditional language of the neighbouring Castillian Kingdom).

The band, however, isn’t from Leon but is from Nashville, Tennessee. They’ve got nothing linking them to actual Leon, or Spain at all, as far as I can tell, except for their name – not unlike gypsies and Egypt, turkeys and Turkey, and French fries and France. The Kings of Leon, a band of brothers, took the inspiration for their name from the first name of their father and their grandfather: Leon.

The Odd One Out

The Kings of Leon are the odd one out, because while all four have names which imply that they’re from somewhere that they’re not, the inventors of the name “The Kings of Leon” were the only ones who knew that the implication was correct.

The people who first started calling gypsies “gypsies” genuinely believed that they came from Egypt. The first person to call a turkey a “Turkey fowl” really was under the impression that it was a bird that had come from, or via, Turkey. And whoever first started spreading the word about the tasty Belgian food they’d discovered while serving overseas really thought that they were a French invention. But the Kings of Leon always knew that they weren’t from Leon (and, presumably, that they weren’t kings).

And as for you? Your sex is on fire. Well, either that or it’s your turkey. You oughta go get it out of the oven if it’s the latter, or – if it’s the former – see if you can get some cream for that. And have a Merry Christmas.

Counterfeit Monkey

Earlier this year, I played Emily Short‘s new game, Counterfeit Monkey, and I’m pleased to say that it’s one of the best pieces of interactive fiction I’ve played in years. I’d highly recommend that you give it a go.

What makes Counterfeit Monkey so great? Well, as you’d expect from an Emily Short game (think Bee, which I reviewed last year, Galatea, and Glass), it paints an engaging and compelling world which feels “bigger” than the fragments of it that you’re seeing: a real living environment in which you’re just another part of the story. The island of Anglophone Atlantis and the characters in it feel very real, and it’s easy to empathise with what’s going on (and the flexibility you have in your actions helps you to engage with what you’re doing). But that’s not what’s most-special about it.

What’s most-special about this remarkable game is the primary puzzle mechanic, and how expertly (not to mention seamlessly and completely) it’s been incorporated into the play experience. Over the course of the game, you’ll find yourself equipped with a number of remarkable tools that change the nature of game objects by adding, removing, changing, re-arranging or restoring their letters, or combining their names with the names of other objects: sort of a “Scrabble® set for real life”.

You start the game in possession of a full-alphabet letter-remover, which lets you remove a particular letter from any word – so you can, for example, change a pine into a pin by “e-removing” it, or you can change a caper into a cape by “r-removing” it (you could go on and “c-remove” it into an ape if only your starting toolset hadn’t been factory-limited to prevent the creation of animate objects).

This mechanic, coupled with a doubtless monumental amount of effort on Emily’s part, makes Counterfeit Monkey have perhaps the largest collection of potential carryable objects of any interactive fiction game ever written. Towards the end of the game, when your toolset is larger, there feels like an infinite number of possible linguistic permutations for your copious inventory… and repeatedly, I found that no matter what I thought of, the author had thought of it first and written a full and complete description of the result (and yes, I did try running almost everything I’d picked up, and several things I’d created, through the almost-useless “Ümlaut Punch”, once I’d found it).

I can’t say too much more without spoiling one of the best pieces of interactive fiction I’ve ever played. If you’ve never played a text-based adventure before, and want a gentler introduction, you might like to go try something more conventional (but still great) like Photopia (very short, very gentle: my review) or Blue Lacuna (massive, reasonably gentle: my review) first. But if you’re ready for the awesome that is Counterfeit Monkey, then here’s what you need to do:

How to play Counterfeit Monkey

-

Install a Glulx interpreter.

I recommend Gargoyle, which provides beautiful font rendering and supports loads of formats. Note that Gargoyle’s UNDO command will not work in Counterfeit Monkey, for technical reasons (but this shouldn’t matter much so long as you SAVE at regular intervals).

Download for Windows, for Mac, or for other systems.

-

Download Counterfeit Monkey

Get Counterfeit Monkey‘s “story file” and open it using your Glulx interpreter (e.g. Gargoyle).

Download it here.

(alternatively, you can use experimental technology to play the game in your web browser: it’ll take a long time to load, though, and you’ll be missing some of the fun optional features, so I wouldn’t recommend it over the “proper” approach above)

The Nontheist Glossary

There’s a word that seems to be being gradually redefined in our collective vocabulary, I was considering recently. That word is “nontheist”. It’s a relatively new word as it is, but in its earliest uses it seems to have been an umbrella term covering a variety of different (and broadly-compatible) theological outlooks.

Here are some of them, in alphabetical order:

| agnostic |

“It is not possible to know whether God exists.” Agnostics believe that it is not possible to know whether or not there are any gods. They vary in the strength of their definition of the word “know”, as well as their definition of the word “god”. Like most of these terms, they’re not mutually-exclusive: there exist agnostic atheists, for example (and, of course, there exist agnostic theists, gnostic atheists, and gnostic theists). |

| antitheist |

“Believing in gods is a bad thing.” Antitheists are opposed to the belief in gods in general, or to the practice of religion. Often, they will believe that the world would be better in the absence of religious faith, to some degree or another. In rarer contexts, the word can also mean an opposition to a specific deity (e.g. “I believe that in God, but I hate Him.”). |

| apatheist |

“If the existence of God could be proven/disproven to me, it would not affect my behaviour.” An apatheist belives that the existence or non-existence of gods is irrelevant. It is perfectly possible to define oneself as a theist, an atheist, or neither, and still be apathetic about the subject. Most of them are atheists, but not all: there are theists – even theists with a belief in a personal god – who claim that their behaviour would be no different even if you could (hypothetically) disprove the existence of that god, to them. |

| atheist |

“There are no gods.” As traditionally-defined, atheists deny the existence of either a specific deity, or – more-commonly – any deities at all. Within the last few hundred years, it has also come to mean somebody who rejects that there is any valid evidence for the existence of a god, a subtle difference which tends to separate absolutists from relativists. If you can’t see the difference between this and agnosticism, this blog post might help. Note also that atheism does not always imply materialism or naturalism: there exist atheists for example who believe in ghosts or in the idea of an immortal soul. |

| deist |

“God does not interfere with the Universe.” Deism is characterised by a belief in a ‘creator’ or ‘architect’ deity which put the universe into motion, but which does has not had any direct impact on it thereafter. Deists may or may not believe that this creator has an interest in humanity (or life at all), and may or may not feel that worship is relevant. Note that deism is nontheistic (and, by some definitions, atheistic) in that it denies the existence of a specific God – a personal God with a concern for human affairs – and so appears on this list even though it’s incompatible with many people’s idea of nontheism. |

| freethinker |

“Science and reason are a stronger basis for decision-making than tradition and authority.” To be precise, freethought is a philosophical rather than a theological position, but its roots lie in the religious: in the West, the term appeared in the 17th century to describe those who rejected a literalist interpretation of the Bible. It historically had a broad crossover with early pantheism, as science began to find answers (especially in the fields of astronomy and biology) which contradicted the religious orthodoxy. Nowadays, most definitions are functionally synonymous with naturalism and/or rationalism. |

| humanist |

“Human development is furthered by reason and ethics, and rejection of superstition.” In the secular sense (as opposed to the word’s many other meanings in other fields), humanism posits that ethical and moral behaviour, for the benefit of individual humans and for society in general, can be attained without religion or a deity. It requires that individuals assess viewpoints for themselves and not simply accept them on faith. Note that like much of this list, secular humanism is not incompatible with other viewpoints – even theism: it’s certainly possible to believe in a god but still to feel that society is always best-served by a human-centric (rather than a faith-based) model. |

| igtheist |

“There exists no definition of God for which one can make a claim of theism or atheism.” One of my favourite nontheistic terms, igtheism (also called ignosticism) holds that words like “god” are not cognitively meaningful and can not be argued for or against. The igtheist holds that the question of whether or not any deities exist is meaningless not because any such deities are uninterested in human affairs (like the deist) or because such a revelation would have no impact upon their life (like the apatheist) but because the terms themselves have no value. The word “god” is either ill-defined, undefinable, or represents an idea that is unfalsifiable. |

| materialist |

“The only reality is matter and energy. All else is an illusion caused by these.” The materialist perspective holds that the physical universe is as it appears to be: an effectively-infinite quantity of matter and energy, traveling through time. It’s incompatible with many forms of theism and spiritual beliefs, but not necessarily with some deistic and pantheistic outlooks: in many ways, it’s more of a philosophical stance than a nontheistic position. It grew out of the philosophy of physicalism, and sharply contrasts the idealist or solipsist thinking. |

| naturalist |

“Everything can be potentially explained in terms of naturally-occurring phenomena.” A closely-related position to that of materialism is that of naturalism. The naturalist, like the materialist, claims that there can be, by definition, no supernatural occurrences in our natural universe, and as such is similarly incompatible with many forms of theism. Its difference, depending on who you ask, tends to be described as being that naturalism does not seek to assume that there is not possibly more to the universe than we could even theoretically be capable of observing, but that does not make such things “unnatural”, much less “divine”. However, in practice, the terms naturalism and materialism are (in the area of nontheism) used interchangeably. The two are also similar to some definitions of the related term, “rationalism”. |

| pantheist |

“The Universe and God are one and the same.” The pantheist believes that it is impossible to distinguish between God and the University itself. This belief is nontheistic because it typically denies the possibility of a personal deity. There’s an interesting crossover between deists and pantheists: a subset of nontheists, sometimes calling themselves “pandeists”, who believe that the Universe and the divine are one and the same, having come into existence of its own accord and running according to laws of its own design. A related but even-less-common concept is panentheism, the belief that the Universe is only a part of an even-greater god. |

| secularist |

“Human activities, and especially corporate activities, should be separated from religious teaching.” The secularist viewpoint is that religion and spiritual thought, while not necessarily harmful (depending on the secularist), is not to be used as the basis for imposing upon humans the a particular way of life. Secularism, therefore, tends to claim that religion should be separated from politics, education, and justice. The reasons for secularism are diverse: some secularists are antitheistic and would prefer that religion was unacceptable in general; others take a libertarian approach, and feel that it is unfair for one person to impose their beliefs upon another; still others simply feel that religion is something to be “kept in the home” and not to be involved in public life. |

| skeptic |

“Religious authority does not intrinsically imply correctness.” Religious skeptics, as implied by their name, doubt the legitimacy of religious teaching as a mechanism to determine the truth. It’s a somewhat old-fashioned term, dating back to an era in which religious skepticism – questioning the authority of priests, for example – was in itself heretical: something which in the West is far rarer than it once was. |

| transtheist |

“I neither accept nor reject the notion of a deity, but find a greater truth beyond both possibilities.” The notion of transtheism, a form of post-theism, is that there exists a religious philosophy that exists both outside and beyond that of both theism and atheism. Differentiating between this and deism, or apatheism, is not always easy, but it’s a similar concept to Jain “transcendence”: the idea that there may or may not exist things which may be called “godlike”, but the ultimate state of being goes beyond this. It can be nontheistic, because it rejects the idea that a god plays a part in human lives, but is not necessarily atheistic. |

However, I’ve observed that the word “nontheist” seems to be finding a new definition, quite apart from the umbrella description above.

In recent years, a number of books have been published on the subject of atheism, some of which – and especially The God Delusion – carry a significant antitheistic undertone. This has helped to inspire the idea that atheism and antitheism are the same thing (which for many atheists, and a tiny minority of antitheists, simply isn’t true), and has lead some people who might otherwise have described themselves as one or several of the terms above to instead use the word “nontheist” as a category of its own.

This “new nontheist” definition is still very much in its infancy, but I’ve heard it described as “areligious, but spiritual”, or “atheistic, but not antitheistic”.

Personally, I don’t like this kind of redefinition. It’s already hard enough to have a reasonable theological debate – having to stop and define your terms every step of the way is quite tiresome! – without people whipping your language out from underneath you right when you were standing on it. I can see how those people who are, for example, “atheistic, but not antitheistic” might want to distance themselves from the (alliterative) antitheistic atheist authors, but can’t they pick a different word?

After all: there’s plenty of terms going spare, above, to define any combination of nontheistic belief, and enough redundancy that you can form a pile of words higher than any Tower of Babel. Then… perhaps… we can talk about religion without stopping to fight over which dictionary is the true word.