Off to Pembrokeshire on holiday I’ve had to stop near Cardiff to put some more charge into the car… which provides the perfect opportunity for the doggo and I to explore a nearby sports field and take in All. The. Smells. 🐶

Tag: travel

Note #26591

Delivery Songs

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

Here in the UK, ice cream vans will usually play a tune to let you know they’re set up and selling1. So when you hear Greensleeves (or, occasionally, Waltzing Matilda), you know it’s time to go and order yourself a ninety-nine.

Imagine my delight, then, when I discover this week that ice cream vans aren’t the only services to play such jaunty tunes! I was sat with work colleagues outside İlter’s Bistro on Meşrutiyet Cd. in Istanbul, enjoying a beer, when a van carrying water pulled up and… played a little song!

And then, a few minutes later – as if part of the show for a tourist like me – a flatbed truck filled with portable propane tanks pulled up. Y’know, the kind you might use to heat a static caravan. Or perhaps a gas barbeque if you only wanted to have to buy a refill once every five years. And you know what: it played a happy little jingle, too. Such joy!

My buddy Cem, who’s reasonably local to the area, told me that this was pretty common practice. The propane man, the water man, etc. would all play a song when they arrived in your neighbourhood so that you’d be reminded that, if you hadn’t already put your empties outside for replacement, now was the time!

And then Raja, another member of my team, observed that in his native India, vegetable delivery trucks also play a song so you know they’re arriving. Apparently the tune they play is as well-standardised as British ice cream vans are. All of the deliveries he’s aware of across his state of Chennai play the same piece of music, so that you know it’s them.

It got me thinking: what other delivery services might benefit from a recognisable tune?

- Bin men: I’ve failed to put the bins out in time frequently enough, over the course of my life, that a little jingle to remind me to do so would be welcome4! (My bin men often don’t come until after I’m awake anyway, so as long as they don’t turn the music on until after say 7am they’re unlikely to be a huge inconvenience to anybody, right?) If nothing else, it’d cue me in to the fact that they were passing so I’d remember to bring the bins back in again afterwards.

- Fish & chip van: I’ve never made use of the mobile fish & chip van that tours my village once a week, but I might be more likely to if it announced its arrival with a recognisable tune.

- Milkman: I’ve a bit of a gripe with our milkman. Despite promising to deliver before 07:00 each morning, they routinely turn up much later. It’s particularly troublesome when they come at about 08:40 while I’m on the school run, which breaks my routine sufficiently that it often results in the milk sitting unseen on the porch until I think to check much later in the day. Like the bin men, it’d be a convenience if, on running late, they at least made their presence in my village more-obvious with a happy little ditty!

- Emergency services: Sirens are boring. How about if blue light services each had their own song. Perhaps something thematic? Instead of going nee-naw-nee-naw, you’d hear, say, de-do-do-do-de-dah-dah-dah and instantly know that you were hearing The Police.

- Evri: Perhaps there’s an appropriate piece of music that says “the courier didn’t bother to ring your doorbell, so now your parcel’s hidden in your recycling box”? Just a thought.

Anyway: the bottom line is that I think there’s an untapped market for jolly little jingles for all kinds of delivery services, and Turkey and India are clearly both way ahead of the UK. Let’s fix that!

Footnotes

1 It’s not unheard of for cruel clever parents to try to teach their young

children that the ice cream van plays music only to let you know it’s sold out of ice cream. A devious plan, although one I wasn’t smart (or evil?) enough to try for

myself.

2 The official line from the government is that the piped water is safe to drink, but every single Turkish person I spoke to on the subject disagreed and said that I shouldn’t listen to… well, most of what the government says. Having now witnessed first-hand the disparity between the government’s line on the unrest following the arrest of the opposition’s presidential candidate and what’s actually happening on the ground, I’m even more inclined to listen to the people.

3 My gas delivery man should also have his own song, of course. Perhaps an instrumental cover of Burn Baby Burn?

4 Perhaps bin men could play Garbage Truck by Sex Bob-Omb/Beck? That seems kinda fitting. Although definitely not what you want to be woken up with if they turn the speakers on too early…

Dan Q found GC6VTEG Galata Bridge #3

This checkin to GC6VTEG Galata Bridge #3 reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

After lunch with my work team in a delightful restaurant overlooking the bridge (which I’m just-about pointing at in the attached photo) I decided to take a diversion on the route back to our coworking space to come and find this geocache, my most-Easterly yet.

The coordinates put me exactly at a likely spot, but it actually took until I’d searched three different candidate hosts before the cache container was in my hand. Signed log and (stealthily) returned to hiding place. TFTC!

Team Desire in Istanbul

With visa complications and travel challenges, this is the very first time that my team – whom I’ve been working with for the last year – have ever all been in the same country, all at the same time.

You can do a lot in a distributed work environment. But sometimes you just have to come together… in celebration of your achievements, in anticipation of what you’ll do next, and in aid of doing those kinds of work that really benefit from a close, communal, same-timezone environment.

Dan Q found GCB3FAQ The Grand Bazaar fossils

This checkin to GCB3FAQ The Grand Bazaar fossils reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

I’m visiting Istanbul to meet with colleagues, but we took some time off from our meetings and work this afternoon to come and get lost in the Grand Bazaar. While browsing the amazing diversity of stalls I found myself staring at the floors, which are made of the same kind of limestone as my kitchen floor (in which my kids love hunting for fossils!). Wouldn’t that make a great Earthcache, I thought… and it turns out it anyway is one! So I spent a little while hunting for the best fossil I could find (I’d hoped for a gastropod of some kind, but had to settle for a bivalve), and sent the answers to the CO. Fantastic stuff. TFTC! FP awarded. And, possibly, FTF!

Istanbul

Note #26131

Note #26129

Note #25554

Note #25538

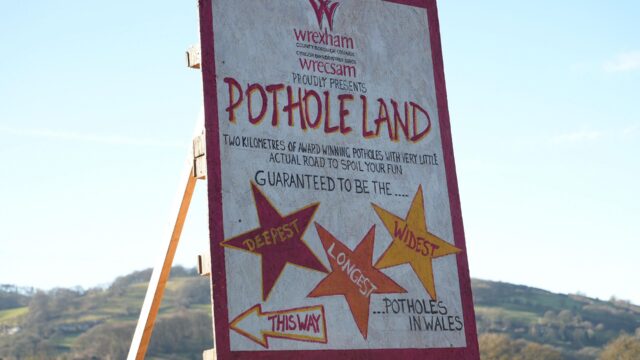

This is funny, but I’m confident Wrexham’s potholes have nothing on the Trinbagonian ones I’ve been experiencing all week, which have sometimes spanned most of the width of a road or been deep enough that dipping a wheel into them would strike the road with your underchassis!

Note #25533

Yesterday, Ruth and I made the first ever attempt at a geohashing expedition in Trinidad & Tobago, successfully finding a hashpoint in Chase Village in the West of Trinidad!

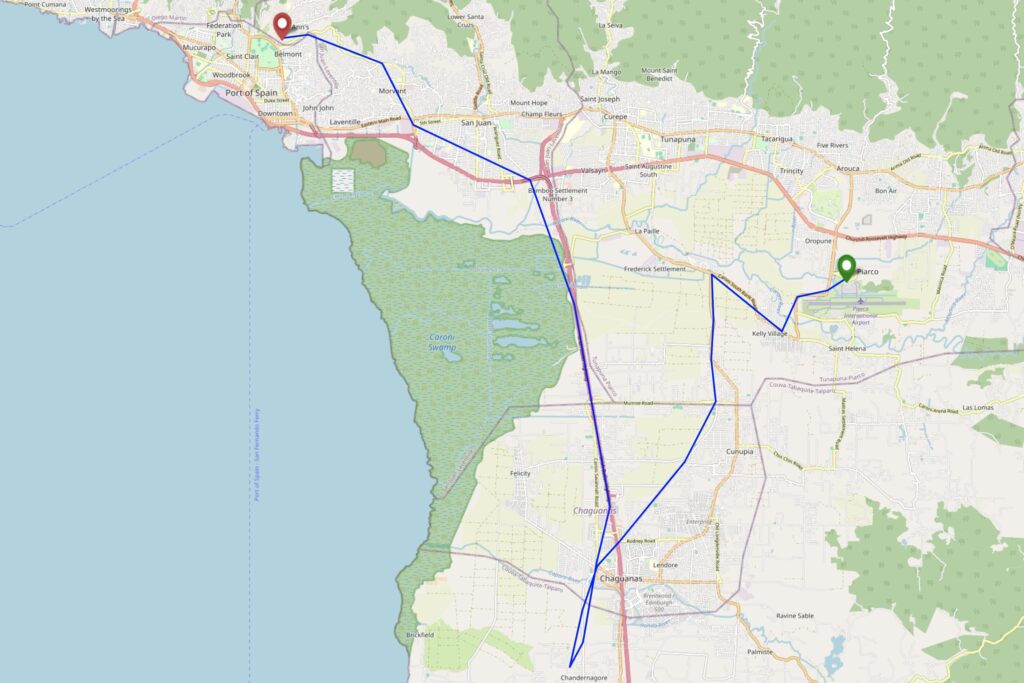

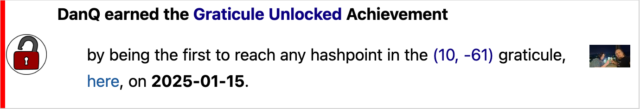

Geohashing expedition 2025-01-15 10 -61

This checkin to geohash 2025-01-15 10 -61 reflects a geohashing expedition. See more of Dan's hash logs.

Location

Empty lot off Bhagan Trace, Chandernagore, near Chase Village, Trinidad.

Participants

Plans

I’ve been on holiday on the islands of Trinidad & Tobago this week. These island nations span graticules that are dominated by the Caribbean and Atlantic Oceans, so it’s little wonder there’s never been an attempted geohashing expedition in them. So when a hashpoint popped-up in a possibly-accessible location, I had to go for it!

For additional context: Trinidad & Tobago is currently under a state of emergency as gang warfare and an escalating murder rate has reached a peak. It’s probably ill-advised to go far off the beaten track, especially as somebody who’s clearly a foreign tourist. The violence and danger is especially prevalent in and around parts of nearby Port of Spain.

As a result, my partner Ruth (wisely) agreed to drive with me to the GZ strictly under the understanding that we’d turn back at a moment’s notice if anything looked remotely sketchy, and we’d take every precaution on the way to, from, and at the hashpoint area (e.g. keeping car doors locked when travelling and not getting out unless necessary and safe to do so, keeping valuables hidden out of sight, knowing the location of the nearest police station at any time, etc.).

I don’t have my regular geohashing kit with me, but I’ve got a smartphone, uLogger sending 5-minute GPS location pings (and the ability to send a location when I press a button in the app, for proof later), and a little bravery, so here we go…

Expedition

Our plane from Tobago landed around 15:20 local time, following an ahead-of-schedule flight assisted by a tailwind from the Atlantic side. We disembarked, collected our bags, and proceeded to pick up a hire car.

Our original plan for our stay in Trinidad had been to drive up to an AirBnB near 10.743817, -61.514248 on Paramin, one of Tobago’s highest summits. However, our experience of driving up Mount Dillon on Tobago earlier in the week showed us that the rural mountain roads around here can be terrifyingly dangerous for non-locals1, and so we chickened out and investigated the possibility of arranging a last-minute stay at a lodge on the edge of the rainforest in Gran Couva, or else failing that a fallback plan of a conventional tourist-centric hotel in the North of Port of Spain.

By this point, we’d determined that the hashpoint was in the old sugar growing region of Caroni, in which our originally-intended accommodation at Gran Couva could be found, and so it seemed feasible that we might be able to safely deviate from our route only a little to get to the hashpoint before reaching our beds. We were particularly keen to be at a place of known safety before the sun set, here in an unusual part of an unfamiliar country! So when the owner of our proposed lodge in Gran Couva called to say that he couldn’t accept our last-minute booking on account of ongoing renovations to his property, we had to quickly arrange ourself a room at our backup hotel.

This put us in an awkward position: now the hashpoint really wasn’t anything-like on the way from the airport to where we’d be staying, and we’d doubtless be spending longer than we’d like to be on the road and increasing the risk that we’d be out after dark. I reassured Ruth, whose appetite for risk is somewhat lower than mine, that if we set out for the hashpoint and anything seemed “off” we could turn around at any time, and we began our journey.

Boosted by her experience of driving on Tobago, Ruth continued to show her rapidly-developing Trinbagonian road skills2.

Despite increasingly heavy traffic on our minor roads, possibly resulting from a crash that had occurred on the Southbound carriageway of the nearby Uriah Butler Highway which was causing drivers to seek a shortcut through the suburbs, we made reasonable time, and were soon in the vicinity of the hashpoint: a mixed-use residential/light commercial estate of the kind that apparently sprung up in places that were, until very late in the 20th century, lands used for sugar cane plantations.

At this point, the maps started to become less and less useful: Google Maps, OpenStreetMap, and Bing Maps completely disagreed as to whether we were driving on Bhagan Trace, Cemetery Street, or Roy Gobin Fifth Avenue, as well as disagreeing on whether we were driving into a cul-de-sac or whether it was possible to loop around at the end to return back to the main roads. It was now almost 17:00 and we were greeted by a large number of cars coming out of the narrow street in the opposite direction to us, going in, and squeezing past us: presumably workers from one of the businesses down here going home for the evening.

My GPS flickered as it tried to make sense of the patchwork of streets, and I asked Ruth to slow down and pull over a couple of times until I was sure that we’d gotten as close as we could, by road. Looking out of my window, I saw the empty lot that I’d scouted from satellite photography, but it was hopelessly overgrown. If the hashpoint was within it, it’d take hours of work and a machete to cut through. The circle of uncertainty jumped around as I tried to finalise the signal without daring to do the obvious thing of holding my phone outside the car window. A handful of locals watched us, the strange white folks sitting in a new car, as I poked at my devices in an effort to check if we were within the circle, or at least if we would be when, imminently, we were forced to park even closer to the side to let a larger vehicle force its way through next to us!

At the point at which I thought we’d made it, I hit the “save waypoint” at 17:06 button and instructed Ruth to drive on. We turned in the road and I started navigating us to our hotel, only thinking to look at the final location I’d tagged later, when we felt safer. We drove back into Port of Spain avoiding Laventille (another zone we’d been particularly recommended to stay away from) while I resisted the urge to double-check my tracklog, instead focussing on trying to provide solid directions through not-always-signposted streets: we had a wrong turning at one point when we came off the highway at Bamboo Settlement No. 1 (10.627952, -61.429083) but thankfully this was an easy mistake to course-correct from.

It was only when I looked at my tracklog, later, that I discovered that the point I’d tagged was exactly 8.59 metres from the hashpoint, plus or minus a circle of uncertainty of… 9 metres. Amazingly, we’d succeeded without even being certain we’d done so. Having failed to get a silly grin photo at the hashpoint, we sufficed to get one while we drank celebratory Prosecco and ate tapas on the rooftop bar of our hotel, looking down on the beautiful bay and imposing mountains of this beautiful if intimidating island.

Tracklog

I didn’t bring my primary GPSr, but my phone keeps a general-purpose tracklog at ~5min/50m intervals, and when I prompt it to. Apologies that this makes my route map look “jumpier” than usual, especially when I’m away from the GZ.

Achievements

Footnotes

1 Often, when speaking to locals, they’d ask if it was our first time in Trinidad & Tobago, and on learning that it was, they’d be shocked to hear that we’d opted to drive for ourselves rather than to hire drivers to take us places: it turns out that the roads are in very-variable condition, from wonderfully-maintained highways to rural trails barely-driveable without a 4×4, but locals in both drive with the same kind of assertive and sometimes reckless attitude.

2 tl;dr of driving in Trinidad & Tobago, as somebody who learned to drive in the UK: (1) if you need to get out of anywhere, don’t wait for anybody to yield because they won’t, even if you theoretically have the right of way: instead, force your way out by obstructing others, (2) drive in the middle of the road wherever possible to make it easier to dodge potholes and other hazards, which are clustered near the soft verges, and swing to your own side of the road only at the last second to avoid collisions, and (3) use your horn as often as you like and for any purpose: to indicate that you want to turn, to warn somebody that you’re there, to tell somebody to move, to say hello to a nearby pedestrian you recognise, or in lieu of turning on your headlights at night, for example. The car horn is a universal language, it seems.

Small-World Serendipity

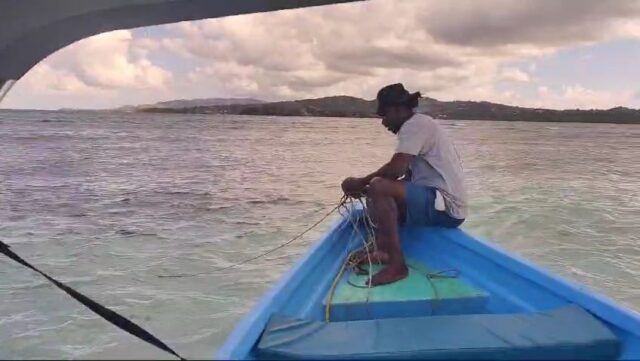

As part of our trip to the two-island republic of Trinidad & Tobago, Ruth and I decided we’d love to take a trip out to Buccoo Reef, off the coast of the smaller island. The place we’ve been staying during the Tobago leg of our visit made a couple of phone calls for us and suggested that we head on down to the boardwalk at nearby Buccoo the next morning where we’d apparently be able to meet somebody from Pops Tours who’d be able to take us out1.

At the allotted time, we found somebody from Pops Tours, who said that he was still waiting for their captain to get there3 and asked us to go sit under the almond tree down the other end of the boardwalk and he’d meet us there.

We’d previously clocked that one of the many small boats moored in the bay was Cariad, and found ourselves intensely curious. All of the other boats we’d seen had English-language names of the kinds you’d expect: a well-equipped pleasure craft optimistically named Fish Finder, a small dual-motorcraft with the moniker Bounty, a brightly-coloured party boat named Cool Runnings, and so on. To travel a third of the way around the world to find a boat named in a familiar Welsh word felt strange.

So imagine our delight when the fella we’d been chatting to came over, explained that their regular tour boat (presumably the one pictured on their website) was in the shop, and said that his cousin would be taking us out in his boat instead… and that cousin came over piloting… the Cariad!

As we climbed aboard, we spotted that he was wearing a t-shirt with a Welsh dragon on it, and a sticker on the side of the helm carried a Welsh flag. What strange coincidence is this, that Ruth and I – who met while living in Wales and come for a romantic getaway to the Caribbean – should happen to find ourselves aboard a literal “love” boat named in Welsh.

There probably aren’t many boats on Earth that fly both the colours of Trinidad & Tobago and of Wales, so we naturally had to ask: did you name this boat?, and why? It turns out that yes, our guide for the day has a love of and fascination with Wales that we never quite got to the bottom of. He’d taken a holiday to Swansea just last year, and would be returning to Wales again later this year.

It’s strange to think that anybody might deliberately take a holiday from a tropical island paradise to come to drizzly cold Wales, but there you have it. It sounds like he was into his football and that might have had an impact on his choice of destination, but choose to believe that maybe there’s a certain affinity between parts of the world that have experienced historical oppression at the hands of a colonial English mindset? Like: perhaps Nigerians would enjoy India as a getaway destination, or Guyanans would dig Mauritius as a holiday spot, too?5

We took a dip at the Nylon Pool, snorkelled around parts of Buccoo Reef (replete with tropical fish of infinite variety and colour), spotted sea turtles zipping around the boat, and took a walk along No Man’s Land (a curious peninsula, long and thin and cut-off from the mainland by mangrove swamps, so-named because Trinidadian law prohibits claiming ownership of any land within a certain distance of the high tide mark… and this particular beach spot consists entirely of such land, coast-to-coast, on account of its extreme narrowness. All in all, it was a delightful boating adventure.

(And for the benefit of the prospective tourist who stumbles upon this blog post in years to come, having somehow hit the right combination of keywords: we paid $400 TTD6 for the pair of us: that’s about £48 GBP at today’s exchange rate, which felt like exceptional value for an amazing experience given that we got the expedition entirely to ourselves.)

But aside from the fantastic voyage we got to go on, this expedition was noteworthy in particular for Cariad and her cymruphile captain. It feels like a special kind of small-world serendipity to discover such immediate and significant common ground with a stranger on the other side of an ocean… to coincide upon a shared interest in a culture and place less-foreign to you than to your host.

An enormous diolch yn fawr7 is due to Pops Tours for this remarkable experience.

Footnotes

1 Can I take a moment to observe how much easier it was to charter a boat in Tobago than it was in Ireland, where I left several answerphone messages but never even got a response? Although in the Irish boat owners’ defence, I was being creepy and mysterious by asking them to take me to random coordinates off the coast.

2 It’s possible that I’ve become slightly obsessed with frigatebirds since arriving here. I first spotted them from our ferry ride from Trinidad to Tobago, noticing their unusually widely-forked tails, striking white (in the case of the females) chests, and relatively-effortless (for a seabird) thermal-chasing flight. But they’re really cool! They’re a seabird… that isn’t waterproof and can’t swim… if they land in the water, they’re at serious risk of drowning! (Their lack of water-resistant feathers helps with their agility, most-likely.) Anyway – while they can snatch shallow-swimming prey out of the water, they seem to prefer to (and get at least 40% of their food from) stealing it from other birds, harassing them in-flight and snatching it from their bills, or else attacking them until they throw up and grabbing their victim’s vomit as it falls. Nature is weird and amazing.

3 Time works differently here. If you schedule something, it’s more a guideline than it is a timetable. When Ruth and I would try paddleboarding a few days later we turned up at the rental shack at their published opening time and hung out on the beach for most of an hour before messaging the owners via the number on their sign. After 15 minutes we got a response that said they’d be there in 10 minutes. They got there 20 minutes later and opened their shop. I’m not complaining – the beach was lovely and just lounging around in the warm sea air with a cold drink from a nearby bar was great – but I learned from the experience that if you’re planning to meet somebody at a particular time here, you might consider bringing a book. (Last-minute postscript: while trying to arrange our next accommodation, alongside writing this post, I was told that I’d receive a phone call “in half an hour” to arrange payment: that was over an hour ago…)

4 Come for the story of small-world serendipity; stay for the copious candid bird photos, I guess?

5 I’ll tell you one thing about coming out to Trinidad & Tobago, it makes you feel occasionally (and justifiably) awkward for the colonial era of the British Empire. Queen Elizabeth II gave royal assent to the bill that granted the islands independence only in 1962, well within living memory, and we’ve met folks who’ve spoken to us about living here when it was still under British rule.

6 Exceptionally-geeky footnote time. The correct currency symbol for the Trinidad & Tobago Dollar is an S-shape with two vertical bars through it, which is not quite the same as the conventional S-shape with a single vertical bar that you’re probably used to seeing when referring to e.g. American, Canadian, or Australian dollars. Because I’m a sucker for typographical correctness, I decided that I’d try to type it “the right way” here in my blog post, and figured that Unicode had solved this problem for me: the single-bar dollar sign that’s easy to type on your keyboard inherits its codepoint from ASCII, I guessed, so the double-bar dollar sign would be elsewhere in Unicode-space, right? Like how Unicode defines single-bar (pound) and double-bar (lira) variants of the “pound sign”. But it turns out this isn’t the case: the double-bar dollar sign, sometimes called cifrão (from Portugese), and the single-bar dollar sign are treated as allographs: they share the same codepoint and only the choice of type face differentiates between them. I can’t type a double-bar dollar sign for you without forcing an additional font upon you, and even if I did it wouldn’t render “correctly” for everybody. Unicode is great, but it’s not perfect.

7 “Thank you very much”, in Welsh, but you probably knew that already.

Top of the World

After driving 300 (vertical) metres up a terrifyingly winding road, we find ourself at ‘Top if the World’, one of Tobago’s highest points. Being able to look down the steep sides of this long-extinct volcano to the sea on both sides is quite spectacular, and the Caribbean and Atlantic horizons seem so far away that you can almost believe you’re seeing the Earth curve.

My camera fails to do this view justice.