In kind-of local news, I see that the folks at Diamond Light Source (which I got to visit last year) have been helping the Bodleian (who I used to work for) to X-ray one of their Herculaneum scrolls (which I’ve written about before). That’s really cool.

Tag: science

Science Weekend

This weekend was full of science.

Research

This started on Saturday with a trip to the Harwell Campus, whose first open day in eight years provided a rare opportunity for us to get up close with cutting edge science (plus some very kid-friendly and accessible displays) as well as visit the synchrotron at Diamond Light Source.

The whole thing’s highly-recommended if you’re able to get to one of their open days in the future, give it a look. I was particularly pleased to see how enthused about science it made the kids, and what clever questions they asked.

For example: the 7-year-old spent a long time cracking a variety of ciphers in the computing tent (and even spotted a flaw in one of the challenge questions that the exhibitors then had to hand-correct on all their handouts!); the 10-year-old enjoyed quizzing a researcher who’d been using x-ray crystallography of proteins.

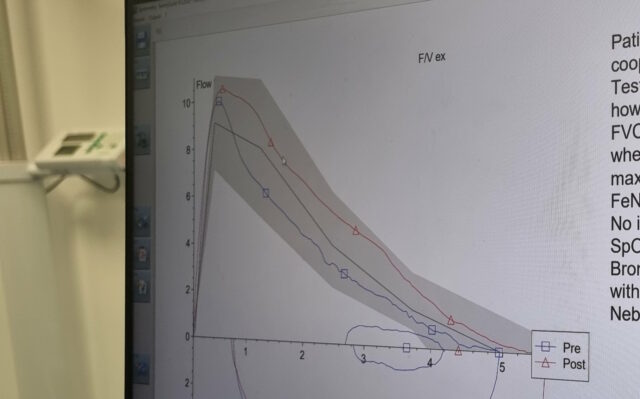

Medicine

And then on Sunday I finally got a long-overdue visit to my nearest spirometry specialist for a suite of experiments to try to work out what exactly is wrong with my lungs, which continue to be a minor medical mystery.

It was… surprisingly knackering. Though perhaps that’s mostly because once I was full of drugs I felt briefly superpowered and went running around the grounds of the wonderfully-named Brill Hill Windmill with the dog until was panting in pretty much the way that I might normally have been, absent an unusually-high dose of medication.

For amusement purposes alone, I’d be more-likely to recommend the first day’s science activities than the second, but I can’t deny that it’s cool to collect a load of data about your own body and how it works in a monitorable, replicable way. And maybe, just maybe, start to get to the bottom of why my breathing’s getting so much worse these last few years!

Water Science #2

Back in 2019, the kids – so much younger back then! – and I helped undertake some crowdsourced citizen science for the Thames WaterBlitz. This year, we’re helping out again.

We’ve moved house since then, but we’re still within the Thames basin and can provide value by taking part in this weekend’s sampling activity. The data that gets collected on nitrate and phosphate levels in local water sources – among other observations – gets fed into an open dataset for the benefit of scientists and laypeople.

It’d have been tempting to be exceptionally lazy and measure the intermittent water course that runs through our garden! It’s an old, partially-culverted drainage ditch1, but it’s already reached the “dry” part of its year and taking a sample wouldn’t be possible right now.

But more-importantly: the focus of this season’s study is the River Evenlode, and we’re not in its drainage basin! So we packed up a picnic and took an outing to the North Leigh Roman Villa, which I first visited last year when I was supposed to be on the Isle of Man with Ruth.

Our lunch consumed, we set off for the riverbank, and discovered that the field between us and the river was more than a little waterlogged. One of the two children had been savvy enough to put her wellies on when we suggested, but the other (who claims his wellies have holes in, or don’t fit, or some other moderately-implausible excuse for not wearing them) was in trainers and Ruth and I needed to do a careful balancing act, holding his hands, to get him across some of the tougher and boggier bits.

Eventually we reached the river, near where the Cotswold Line crosses it for the fifth time on its way out of Oxford. There, almost-underneath the viaduct, we sent the wellie-wearing eldest child into the river to draw us out a sample of water for testing.

Looking into our bucket, we were pleased to discover that it was, relatively-speaking, teeming with life: small insects and a little fish-like thing wriggled around in our water sample2. This, along with the moorhen we disturbed3 as we tramped into the reeds, suggested that the river is at least in some level of good-health at this point in its course.

We were interested to observe that while the phosphate levels in the river were very high, the nitrate levels are much lower than they were recorded near this spot in a previous year. Previous years’ studies of the Evenlode have mostly taken place later in the year – around July – so we wondered if phosphate-containing agricultural runoff is a bigger problem later in the Spring. Hopefully our data will help researchers answer exactly that kind of question.

Regardless of the value of the data we collected, it was a delightful excuse for a walk, a picnic, and to learn a little about the health of a local river. On the way back to the car, I showed the kids how to identify wild garlic, which is fully in bloom in the woods nearby, and they spent the rest of the journey back chomping down on wild garlic leaves.

The car now smells of wild garlic. So I guess we get a smelly souvenir from this trip, too4!

Footnotes

1 Our garden ditch, long with a network of similar channels around our village, feeds into Limb Brook. After a meandering journey around the farms to the East this eventually merges with Chill Brook to become Wharf Stream. Wharf Stream passes through a delightful nature reserve before feeding into the Thames near Swinford Toll Bridge.

2 Needless to say, we were careful not to include these little animals in our chemical experiments but let them wait in the bucket for a few minutes and then be returned to their homes.

3 We didn’t catch the moorhen in a bucket, though, just to be clear.

4 Not counting the smelly souvenir that was our muddy boots after splodging our way through a waterlogged field, twice

Bumblebees surprise scientists with ‘sophisticated’ social learning

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

First, bees had to push a blue lever that was blocking a red lever… too complex for a bee to solve on its own. So scientists trained some bees by offering separate rewards for the first and second steps.

These trained bees were then paired with bees who had never seen the puzzle, and the reward for the first step was removed.

Some of the untrained bees were able to learn both steps of the puzzle by watching the trained bees, without ever receiving a reward for the first step.

…

This news story is great for two reasons.

Firstly, it’s a really interesting experimental result. Just when you think humankind’s learned everything they ever will about the humble bumblebee (humblebee?), there’s something more to discover.

That a bee can be trained to solve a complex puzzle by teaching it to solve each step independently and then later combining the steps isn’t surprising. But that these trained bees can pass on their knowledge to their peers (bee-ers?); who can then, one assumes, pass it on to yet other bees. Social learning.

Which, logically, means that a bee that learns to solve the two-lever puzzle second-hand would have a chance of solving an even more-complex three-lever puzzle; assuming such a thing is within the limits of the species’ problem-solving competence (I don’t know for sure whether they can do this, but I’m a firm bee-lever).

But the second reason I love this story is that it’s a great metaphor in itself for scientific progress. The two-lever problem is, to an untrained bee, unsolvable. But if it gets a low-effort boost (a free-bee, as it were) by learning from those that came before it, it can make a new discovery.

(I suppose the secret third reason the news story had me buzzing was that I appreciated the opportunities for puns that it presented. But you already knew that I larva pun, right?)

Announcers and Automation

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

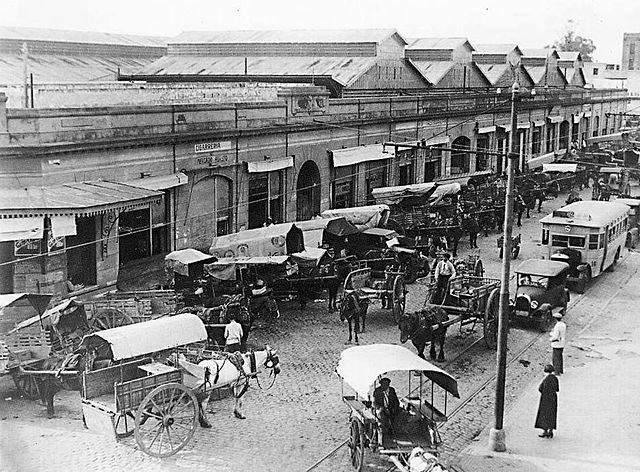

Nowadays if you’re on a railway station and hear an announcement, it’s usually a computer stitching together samples1. But back in the day, there used to be a human with a Tannoy microphone sitting in the back office, telling you about the platform alternations and destinations.

I had a friend who did it as a summer job, once. For years afterwards, he had a party trick that I always quite enjoyed: you’d say the name of a terminus station on a direct line from Preston, e.g. Edinburgh Waverley, and he’d respond in his announcer-voice: “calling at Lancaster, Oxenholme the Lake District, Penrith, Carlisle, Lockerbie, Haymarket, and Edinburgh Waverley”, listing all of the stops on that route. It was a quirky, beautiful, and unusual talent. Amazingly, when he came to re-apply for his job the next summer he didn’t get it, which I always thought was a shame because he clearly deserved it: he could do the job blindfold!

There was a strange transitional period during which we had machines to do these announcements, but they weren’t that bright. Years later I found myself on Haymarket station waiting for the next train after mine had been cancelled, when a robot voice came on to announce a platform alteration: the train to Glasgow would now be departing from platform 2, rather than platform 1. A crowd of people stood up and shuffled their way over the footbridge to the opposite side of the tracks. A minute or so later, a human announcer apologised for the inconvenience but explained that the train would be leaving from platform 1, and to disregard the previous announcement. Between then and the train’s arrival the computer tried twice more to send everybody to the wrong platform, leading to a back-and-forth argument between the machine and the human somewhat reminiscient of the white zone/red zone scene from Airplane! It was funny perhaps only because I wasn’t among the people whose train was in superposition.

Clearly even by then we’d reached the point where the machine was well-established and it was easier to openly argue with it than to dig out the manual and work out how to turn it off. Nowadays it’s probably even moreso, but hopefully they’re less error-prone.

When people talk about how technological unemployment, they focus on the big changes, like how a tipping point with self-driving vehicles might one day revolutionise the haulage industry… along with the social upheaval that comes along with forcing a career change on millions of drivers.

But in the real world, automation and technological change comes in salami slices. Horses and carts were seen alongside the automobile for decades. And you still find stations with human announcers. Even the most radically-disruptive developments don’t revolutionise the world overnight. Change is inevitable, but with preparation, we can be ready for it.

Footnotes

1 Like ScotRail’s set, voiced by Alison McKay, which computers can even remix for you over a low-fi hiphop beat if you like.

Using every car parking space in a supermarket car park

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

For the last six years I’ve kept a spreadsheet listing every parking spot I’ve used at the local supermarket in a bid to park in them all. This week I completed my Magnum Opus! A thread.

I live in Bromley and almost always shop at the same Sainsbury’s in the centre of town, here’s a satellite view of their car park. It’s a great car park because you can always get a space and it is laid out really well. Comfortably in my top 5 Bromley car parks.

After quite a few years of going each week I started thinking about how many of the different spots I’d parked in and how long it would take to park in them all. My life is one long roller coaster.

…

A glorious story from a man with the kind of dedication that would have gotten him far in CNPS back in the day (I wonder if Claire ever got past 13 points…).

This is the kind of thing that I occasionally consider adding to the list of mundane shit I track about my life. But then I start thinking about the tracking infrastructure and I end up adding far more future-proofing than I intend: I start thinking about tracking how often my hayfever causes me problems so I can correlate it to the time and the location data I already record to work out which tree species’ pollen affects me the most. Or tracking a variety of mood metrics so I can see if, as I’ve long suspected, the number of unread emails in my inboxen negatively correlates to my general happiness.

Measure all the things!

Gratitude

In these challenging times, and especially because my work and social circles have me communicate regularly with people in many different countries and with many different backgrounds, I’m especially grateful for the following:

- My partner, her husband, and I each have jobs that we can do remotely and so we’re not out-of-work during the crisis.

- Our employers are understanding of our need to reduce and adjust our hours to fit around our new lifestyle now that schools and nurseries are (broadly) closed.

- Our kids are healthy and not at significant risk of serious illness.

- We’ve got the means, time, and experience to provide an adequate homeschooling environment for them in the immediate term.

- (Even though we’d hoped to have moved house by now and haven’t, perhaps at least in part because of COVID-19,) we have a place to live that mostly meets our needs.

- We have easy access to a number of supermarkets with different demographics, and even where we’ve been impacted by them we’ve always been able to work-around the where panic-buying-induced shortages have reasonably quickly.

- We’re well-off enough that we were able to buy or order everything we’d need to prepare for lockdown without financial risk.

- Having three adults gives us more hands on deck than most people get for childcare, self-care, etc. (we’re “parenting on easy mode”).

- We live in a country in which the government (eventually) imposed the requisite amount of lockdown necessary to limit the spread of the virus.

- We’ve “only” got the catastrophes of COVID-19 and Brexit to deal with, which is a bearable amount of crisis, unlike my colleague in Zagreb for example.

Whenever you find the current crisis getting you down, stop and think about the things that aren’t-so-bad or are even good. Stopping and expressing your gratitude for them in whatever form works for you is good for your happiness and mental health.

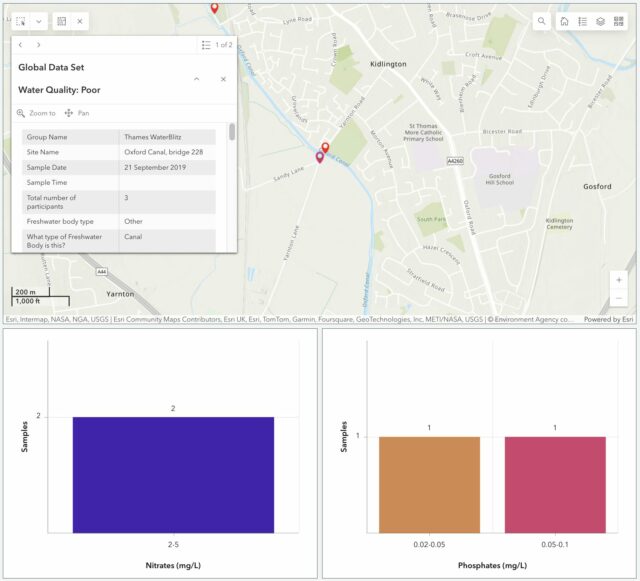

Water Science

This afternoon, the kids and I helped with some citizen science as part of the Thames WaterBlitz, a collaborative effort to sample water quality of the rivers, canals, and ponds of the Thames Valley to produce valuable data for the researchers of today and tomorrow.

My two little science assistants didn’t need any encouragement to get out of the house and into the sunshine and were eager to go. I didn’t even have to pull out my trump card of pointing out that there were fruiting brambles along the length of the canal. As I observed in a vlog last year, it’s usually pretty easy to motivate the tykes with a little foraging.

The EarthWatch Institute had provided all the chemicals and instructions we needed by post, as well as a mobile app with which to record our results (or paper forms, if we preferred). Right after lunch, we watched their instructional video and set out to the sampling site. We’d scouted out a handful of sites including some on the River Cherwell as it snakes through Kidlington but for this our first water-watch expedition we figured we’d err on the safe side and aim to target only a single site: we chose this one both because it’s close to home and because a previous year’s citizen scientist was here, too, improving the comparability of the results year-on-year.

Plus, this expedition provided the opportunity to continue to foster the 5 year-old’s growing interest in science, which I’ve long tried to encourage (we launched bottle rockets the other month!).

Our results are now online, and we’re already looking forward to seeing the overall results pattern (as well as taking part in next year’s WaterBlitz!).

Note #14651

On this day 50 years ago launched the first mission to take people to the moon. As part of #GlobalRocketLaunch day the 5-year-old and I fired off stomp rockets and learned about the science and engineering of Apollo 11.

The man who made Einstein world-famous

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

It is hard to imagine a time when Albert Einstein’s name was not recognised around the world.

But even after he finished his theory of relativity in 1915, he was nearly unknown outside Germany – until British astronomer Arthur Stanley Eddington became involved.

Einstein’s ideas were trapped by the blockades of the Great War, and even more by the vicious nationalism that made “enemy” science unwelcome in the UK.

But Einstein, a socialist, and Eddington, a Quaker, both believed that science should transcend the divisions of the war.

It was their partnership that allowed relativity to leap the trenches and make Einstein one of the most famous people on the globe.

…

I hadn’t heard this story before, and it’s well-worth a read.

The Side Effects of Vaccines – How High is the Risk?

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Kurzgesagt tells it like it is. The thing I love the most about this video is the clickbaity title that’s clearly geared to try to get the attention of antivaxxers and the “truth teaser” opening which plays a little like many antivaxxer videos and other media… and then the fact that it goes and drops a science bomb on all the fools who tout their superstitious bollocks. Awesome.

Mercury is the closest planet to all seven other planets

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Just showing the simulation which we used to validate the Whirly Dirly Corollary. Kind of a fun fact about our Solar System and orbiting bodies in general. Check out our Physics Today article!

Alka-Seltzer added to spherical water drop in microgravity

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This is just…wooooah. Proper “dude, my hands are huge” grade moment, for me, when I watched the bubbles form in the droplet of water. I had an idea about what would happen, and I was partially right, but by the time we were onto the third run-through of this experiment I realised that I’d been seeing more in it every single time.

Microgravity is weird, y’all.

The 500-Year-Long Science Experiment

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

In 2014, microbiologists began a study that they hope will continue long after they’re dead.

In the year 2514, some future scientist will arrive at the University of Edinburgh (assuming the university still exists), open a wooden box (assuming the box has not been lost), and break apart a set of glass vials in order to grow the 500-year-old dried bacteria inside. This all assumes the entire experiment has not been forgotten, the instructions have not been garbled, and science—or some version of it—still exists in 2514.

…

This is a biology experiment that’s planned to run for half a millenium. How does one even make such a thing possible?

Thinking about the difficulties in constructing a message that may be understood for generations into the future reminds me of the work done on a possible marking system for nuclear waste disposal (which would need to continue to carry the message that a place is dangerous for ten thousand years).

This kind of philosophical thinking may require further work, though, if we’re ever to send spacecraft on interstellar journeys: another kind of “long” experiment. How might we preserve the records of what we’ve done, so that our descendants have the opportunity to continue our work, in a way that promotes the iterative translation and preservation of the messages that are required to support it? For example: if an experiment is to be understandable if rediscovered after a hypothetical future dark age, what precautions do we need to take today?

Elemental haiku

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Chlorine

Low road or high road?

World War I. Gas in trenches.

Or salt shared, tears shed.

A haiku for every element on the periodic table up to atomic weight 103, and also one for the as-yet-unsynthesised ununennium, I especially like magnesium’s.