This is a blog post about things that make me nostalgic for other things that, objectively, aren’t very similar…

When I hear Dawnbreaker, I feel like I’m nine years old…

…and I’ve been allowed to play OutRun on the arcade cabinet at West View Leisure Centre. My swimming lesson has finished, and normally I should go directly home.

On those rare occasions I could get away1 with a quick pause in the lobby for a game, I’d gravitate towards the Wonderboy machine. But there was something about the tactile controls of OutRun‘s steering wheel and pedals that gave it a physicality that the “joystick and two buttons” systems couldn’t replicate.

OutRun‘s main theme, Magical Sound Shower, doesn’t actually sound much like Dawnbreaker. But both tracks somehow feel like… “driving music”?

(It should, I suppose: Metrik wrote Dawnbreaker explicitly for that purpose in the first place, for use in a videogame I haven’t played3.)

But somehow when I’m driving or cycling and it this song comes on, I’m instantly transported back to those occasionally-permitted childhood games of OutRun4.

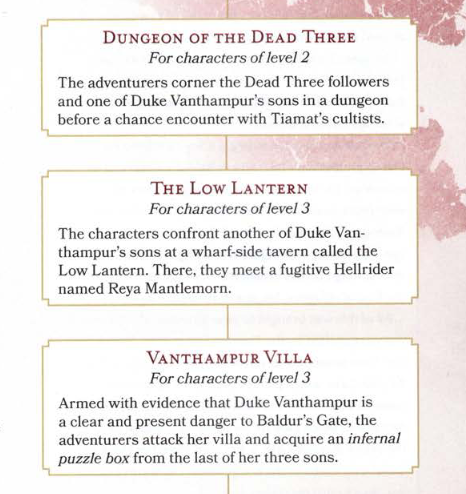

When I start a new Ruby project, I feel like I’m eleven years old…

…and I’m writing Locomotive BASIC on the family’s Amstrad CPC. Like many self-taught coders in the 1980s, my journey as a programmer begin with BASIC. When I transitioned from that to more “grown-up” languages5 I missed the feeling of programming in an environment where every line brought me joy.

HELLO WORLD, but it’s pretty-similar.

At first I assumed that the tedious bits and the administrative overhead (linking, compiling, syntactical surprises, arcane naming conventions…) was just what “real”, “grown-up” programming was supposed to feel like. But Ruby helped remind me that programming can be fun for its own sake. Not just because of the problems you’re solving or the product you’re creating, but just for the love of programming.

The experience of starting a new Ruby project feels just like booting up my Amstrad CPC and being able to joyfully write code that will just work.

I still learn new programming languages because, well, I love doing so. But I’m yet to find one that makes me want to write poetry in it in the way that Ruby does.

When I hear In Yer Face, I feel like I’m thirteen years old…

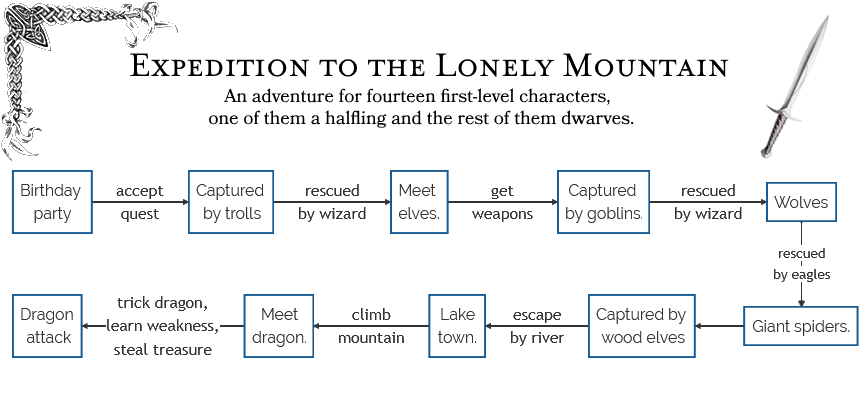

…and I’m painting Advanced HeroQuest miniatures6 in the attic at my dad’s house.

I’ve cobbled together a stereo system of my very own, mostly from other people’s castoffs, and set it up in “The Den”, our recently-converted attic7, and my friends and I would make and trade mixtapes with one another. One tape began with 808 State’s In Yer Face8, and it was often the tape that I would put on when I’d sit down to paint.

In a world before CD audio took off, “shuffle” wasn’t a thing, and we’d often listen to all of the tracks on a medium in sequence9.

That was doubly true for tapes, where rewinding and fast-forwarding took time and seeking for a particular track was challenging compared to e.g. vinyl. Any given song would loop around a lot if I couldn’t be bothered to change tapes, instead just flipping again and again10. But somehow it’s whenever I hear In Yer Face11 that I’m transported right back to that time, in a reverie so corporeal that I can almost smell the paint thinner.

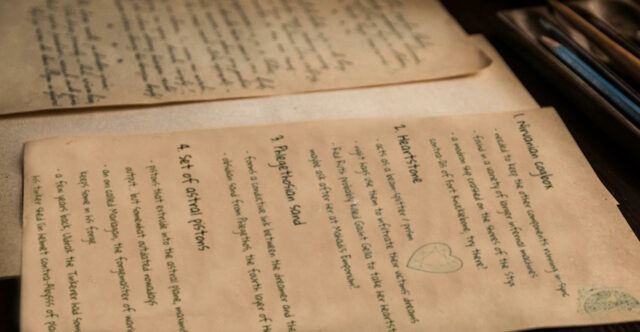

When I see a personal Web page, I (still) feel like I’m fifteen years old…

…and the Web is on the cusp of becoming the hot “killer application” for the Internet. I’ve been lucky enough to be “online” for a few years by now12, and basic ISP-provided hosting would very soon be competing with cheap, free, and ad-supported services like Geocities to be “the place” to keep your homepage.

Since its early days, the Web has always been an expressive medium. Open a Web browser, and you’re seeing a blank canvas of potential. And with modern browser debug tools, you don’t even have to reach for your text editor to begin to create in that medium.

The limitations of that medium in the pre-CSS era were a cause for inspiration, not confinement: web pages of the mid-1990s would use all kinds of imaginative tricks to lay out and style their content!

Nowadays, even with a hugely-expanded toolbox, virtually every corporate homepage fundamentally looks the same:

- Logo in the top left

- Search and login in the top right, if applicable

- A cookie/privacy notice covering everything until you work out the right incantation to make it go away without surrendering your firstborn child

- A “hero banner“

- Some “below the fold” content that most people skip over

- A fat footer with several columns of links, to ensure that all the keywords are there so that people never have to see this page and the search engine will drop them off at relevant child page and not one of their competitors

- Finally, a line of icons representing various centralised social networks: at least one is out-of-date, either because (a) it’s been renamed, (b) it’s changed its branding, or (c) nobody with any moral fortitude uses that network any more14

But before the corporate Web became the default, personal home pages brought a level of personality that for a while I worried was forever dead.

But… personal home pages didn’t die: everybody is free to write websites, so they’re still out there15, and they’re amazing. Look at this magic:

Last year, I wrote:

Writing HTML is punk rock. A “platform” is the tool of the establishment.

That still feels right to me. 🤘

So… it turns out that I get nostalgic about technology in the same way as I get nostalgic about music.

Footnotes

1 My dad in particular considered arcade games financially wasteful when we, y’know, had a microcomputer at home that could load a text-based adventure from an audiotape and be ready to play in “only” about 3-5 minutes.

2 Have you played Sonic Racing: CrossWorlds? The first time I played it I was overwhelmed by the speed and colours of the game: it’s such a high-octane visual feast. Well that’s what OutRun felt like to those of us who, in the 1980s, were used to much-simpler and slower arcade games.

3 Also, how cool is it that Metrik has a blog, in this day and age? Max props.

4 Did you hear, by the way, that there’s talk of a movie adaptation of OutRun, which could turn out to be the worst videogame-to-movie concept that I’ll ever definitely-watch.

5 In very-approximate order: C, Assembly, Pascal, HTML, Perl, Visual Basic (does that even count as a “grown-up” language?), Java, Delphi, JavaScript, PHP, SQL, ASP (classic, pre-.NET), CSS, Lisp, C#, Ruby, Python (though I didn’t get on with it so well), Go, Elixir… plus many others I’m sure!

6 Or possibly they were Warhammer Quest miniatures by this point; probably this memory spans one, and also the other, blended together.

7 Eventually my dad and I gave up on using the partially-boarded loft to intermittently build a model railway layout, mostly using second-hand/trade-in parts from “Trains & Transport”, which was exactly the nerdy kind of model shop you’re imagining right now: underlit and occupied by a parade of shuffling neckbeards, between whom young-me would squeeze to see if the mix-and-match bin had any good condition HO-gauge flexitrack. We converted the attic and it became “The Den”, a secondary space principally for my use. This was, in the most part, a concession for my vacating of a large bedroom and instead switching to the smallest-imaginable bedroom in the house (barely big enough to hold a single bed!), which in turn enabled my baby sister to have a bedroom of her own.

8 My copy of In Yer Face was possibly recorded from the radio by my friend ScGary, who always had a tape deck set up with his finger primed close to the record key when the singles chart came on.

9 I soon learned to recognise “my” copy of tracks by their particular cut-in and -out points, static and noise – some of which, amazingly, survived into the MP3 era – and of course the tracks that came before or after them, and there are still pieces of music where, when I hear them, I “expect” them to be followed by something that they used to some mixtape I listened to a lot 30+ years ago!

10 How amazing a user interface affordance was it that playing one side of an audio cassette was mechanically-equivalent to (slowly) rewinding the other side? Contrast other tape formats, like VHS, which were one-sided and so while rewinding there was literally nothing else your player could be doing. A “full” audio cassette was a marvellous thing, and I especially loved the serendipity where a recognisable “gap” on one side of the tape might approximately line-up with one on the other side, meaning that you could, say, flip the tape after the opening intro to one song and know that you’d be pretty-much at the start of a different one, on the other side. Does any other medium have anything quite analogous to that?

11 Which is pretty rare, unless I choose to put it on… although I did overhear it “organically” last summer: it was coming out of a Bluetooth speaker in a narrowboat moored in the Oxford Canal near Cropredy, where I was using the towpath to return from a long walk to nearby Northamptonshire where I’d been searching for a geocache. This was a particularly surprising place to overhear such a song, given that many of the boats moored here probably belonged to attendees of Fairport’s Cropredy Convention, at which – being a folk music festival – one might not expect to see significant overlap of musical taste with “Madchester”-era acid house music!

12 My first online experiences were on BBS systems, of which my very first was on a mid-80s PC1512 using a 2800-baud acoustic coupler! I got onto the Internet at a point in the early 90s at which the Web existed… but hadn’t yet demonstrated that it would eventually come to usurp the services that existed before it: so I got to use Usenet, Gopher, Telnet and IRC before I saw my first Web browser (it was Cello, but I switched to Netscape Navigator soon after it was released).

13 On the rare occasion I close my browser, these days, it re-opens with whatever hundred or so tabs I was last using right back where I left them. Gosh, I’m a slob for tabs.

14 Or, if it’s a Twitter icon: all three of these.

15 Of course, they’re harder to find. SEO-manipulating behemoths dominate the search results while social networks push their “apps” and walled gardens to try to keep us off the bigger, wider Web… and the more you cut both our of your online life, the calmer and happier you’ll be.

16 The sites featured in the video are: praze, elle’s homepage, sctech, Konfetti Explorations (Marisabel), Frills (check her character sheet “about” page!), mrkod, Raven Winters, Cobb, ajazz, Yusuf Ertan, Alvin Bryan, Armando Cordova, Ens/DepartedGlories, and Jamie Tanna.