What can I make it do?

It’s been said that when faced with a new piece of technology, a normal person asks “what does it do?”, but a hacker asks “what can I make it do?”.

This kind of curiosity is integral to a hacker mindset.

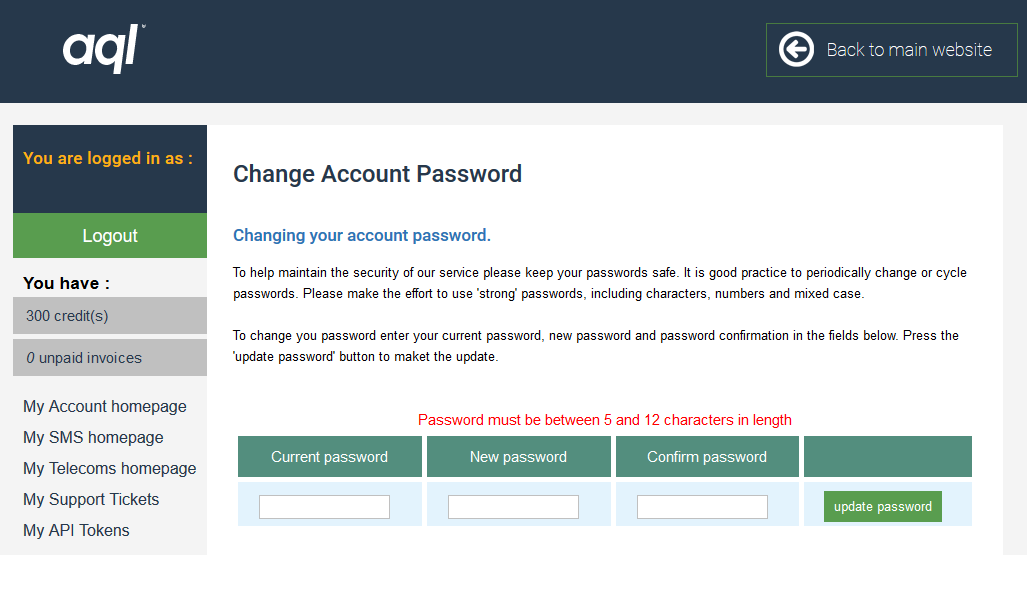

I can trace my hacker roots back further than my first experience of using an RM Nimbus M-Series in circa 19922. But there was something particular about my experience of this popular piece of British edutech kit which provided me with a seminal experience that shaped my “hacker identity”. And it’s that experience about which I’d like to tell you:

Shortly after I started secondary school, they managed to upgrade their computer lab from a handful of Nimbus PC-186s to a fancy new network of M-Series PC-386s. The school were clearly very proud of this cutting-edge new acquisition, and we watched the teachers lay out the manuals and worksheets which smelled fresh and new and didn’t yet have their corners frayed nor their covers daubed in graffiti.

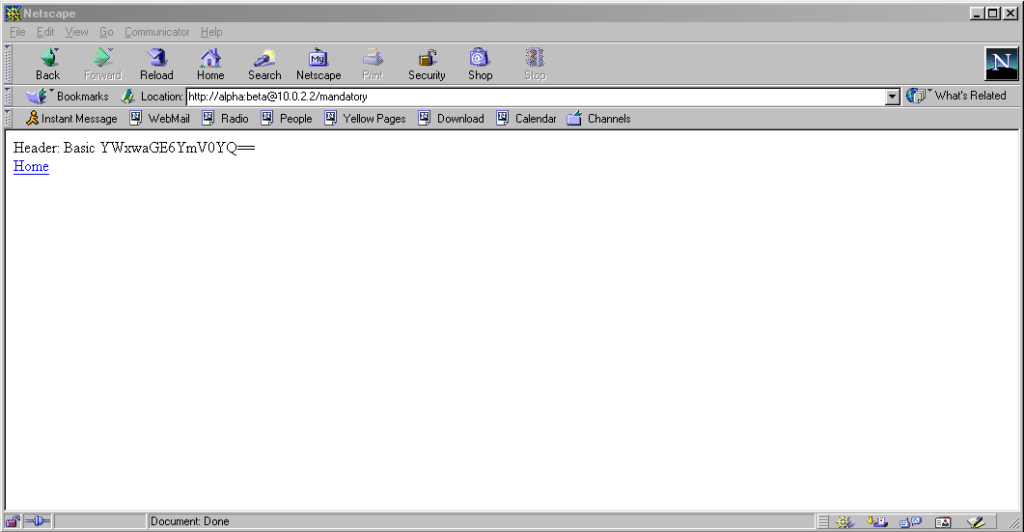

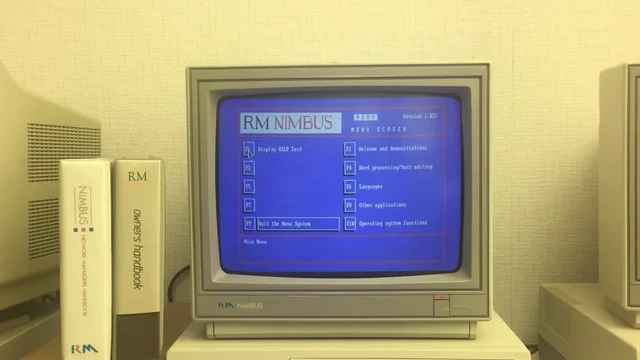

Program Manager

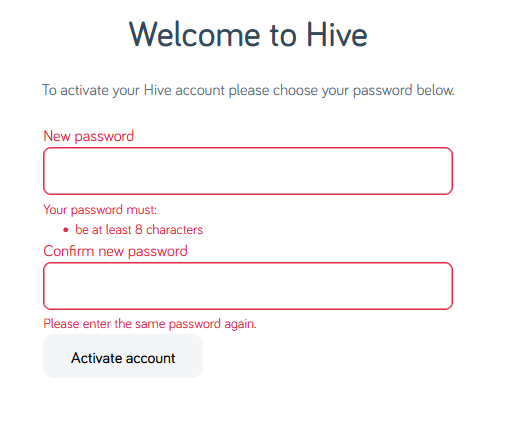

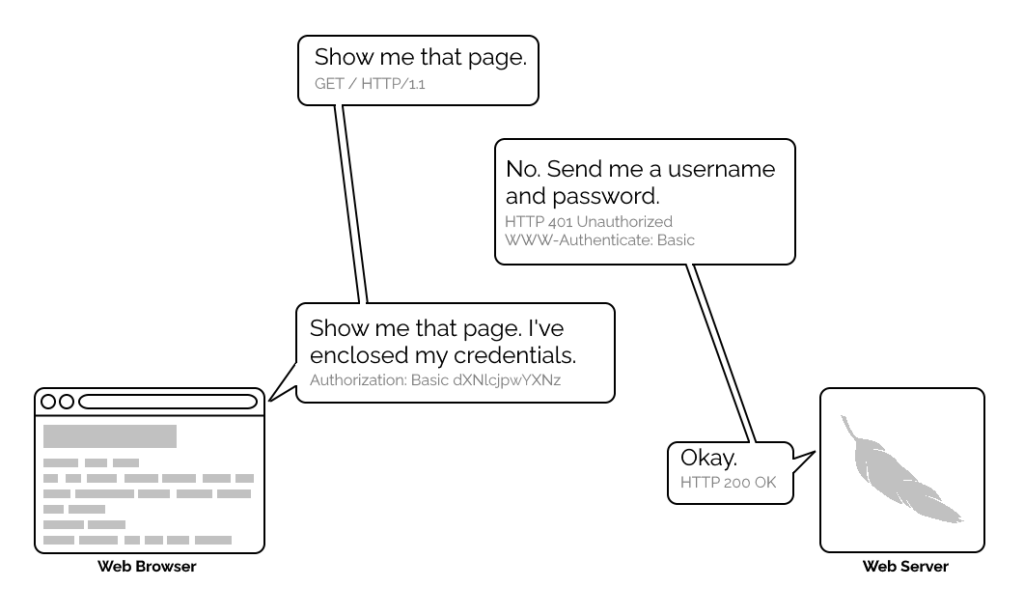

The new ones ran Windows 3 (how fancy!). Well… kind-of. They’d been patched with a carefully-modified copy of Program Manager that imposed a variety of limitations. For example, they had removed the File > Run… menu item, along with an icon for File Manager, in order to restrict access to only the applications approved by the network administrator.

A special program was made available to copy files between floppy disks and the user’s network home directory. This allowed a student to take their work home with them if they wanted. The copying application – whose interface was vastly inferior to File Manager‘s – was limited to only copying files with extensions in its allowlist. This meant that (given that no tool was available that could rename files) the network was protected from anybody introducing any illicit file types.

Bring a .doc on a floppy? You can copy it to your home directory. Bring a .exe? You can’t even see it.

To young-teen-Dan, this felt like a challenge. What I had in front of me was a general-purpose computer with a limited selection of software but a floppy drive through which media could be introduced. What could I make it do?

Spoiler: eventually I ended up being able to execute pretty much anything I wanted, but we’ll get to that. The journey is the important part of the story. I didn’t start by asking “can I trick this locked-down computer lab into letting my friends and I play Doom deathmatches on it?” I started by asking “what can I make it do?”; everything else built up over time.

I started by playing with macros. Windows used to come with a tool called Recorder,3 which you could use to “record” your mouse clicks and keypresses and play them back.

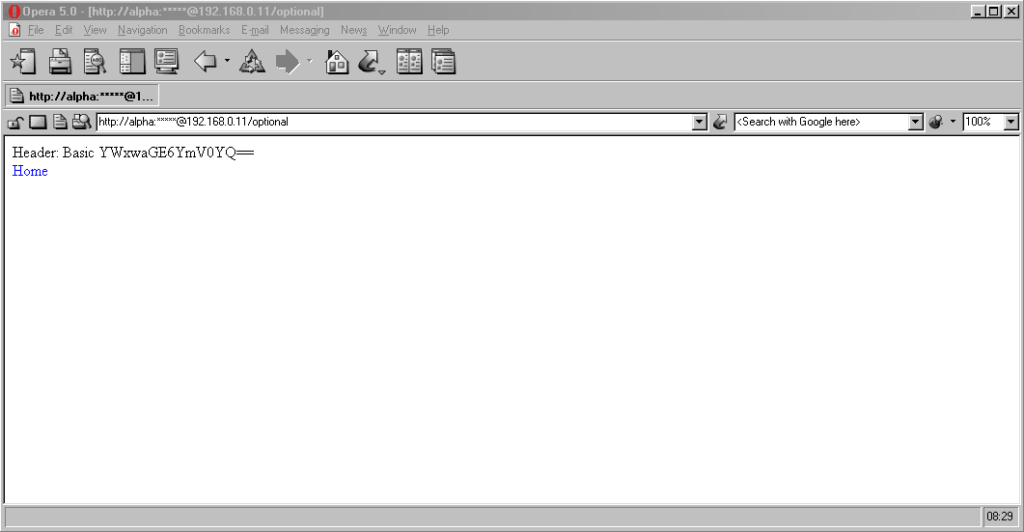

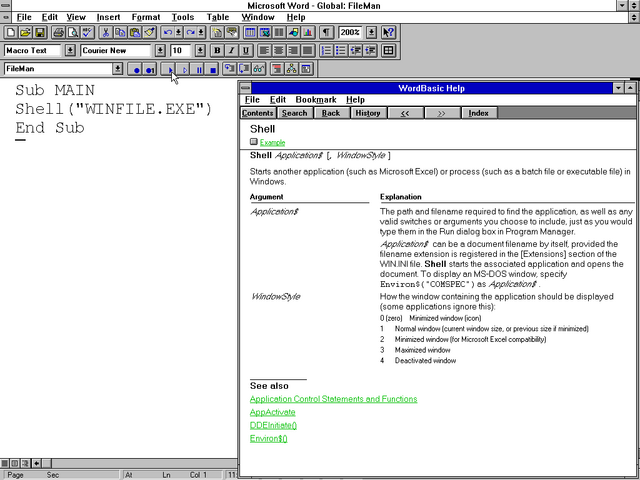

Microsoft Word

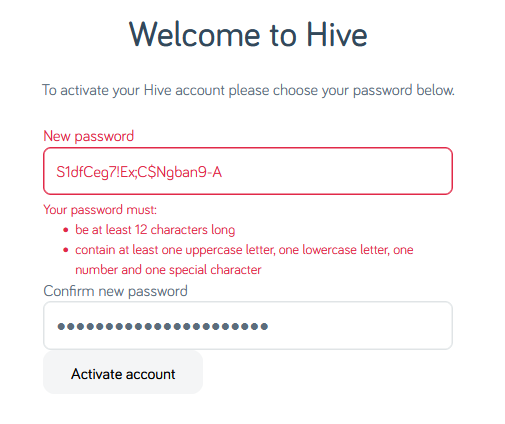

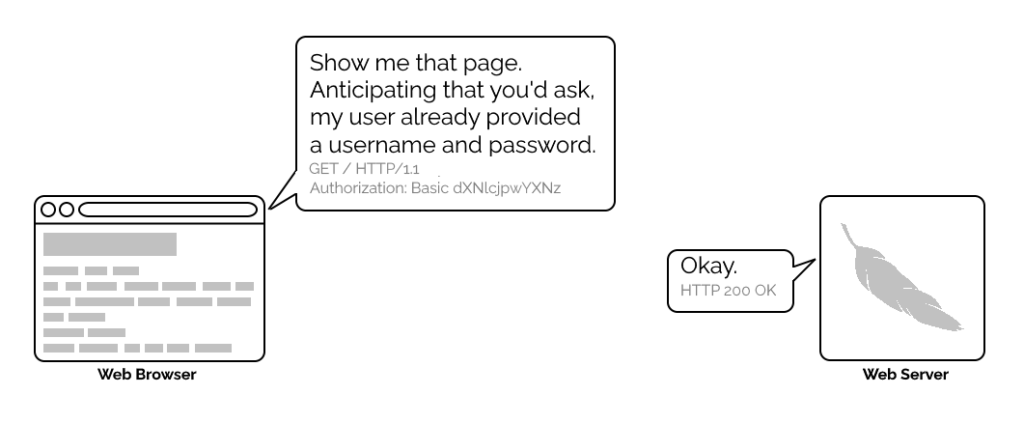

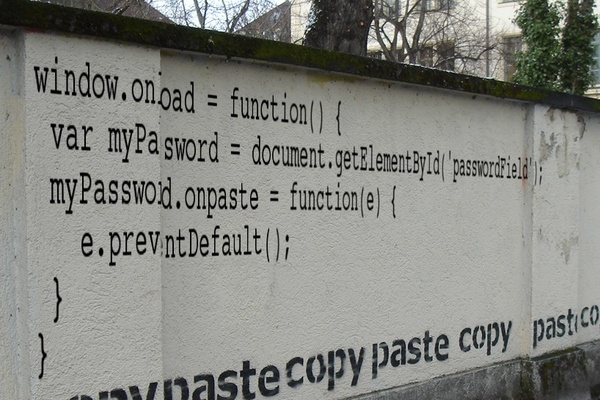

Then I noticed that Microsoft Word also had a macro recorder, but this one was scriptable using a programming language called WordBasic (a predecessor to Visual Basic for Applications). So I pulled up the help and started exploring what it could do.

And as soon as I discovered the Shell function, I realised that

the limitations that were being enforced on the network could be completely sidestepped.

Now that I could run any program I liked, I started poking the edges of what was possible.

- Could I get a MS-DOS prompt/command shell? Yes, absolutely5.

- Could I write to the hard disk drive? Yes, but any changes got wiped when the computer performed its network boot.

- Could I store arbitrary files in my personal network storage? Yes, anything I could bring in on floppy disks6 could be persisted on the network server.

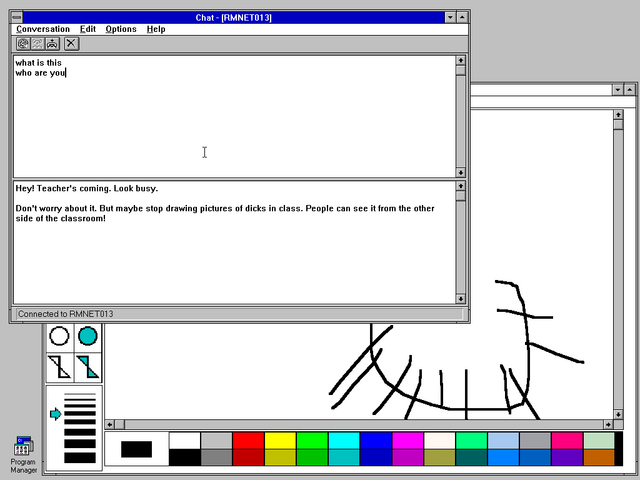

I didn’t have a proper LAN at home7 So I really enjoyed the opportunity to explore, unfettered, what I could get up to with Windows’ network stack.

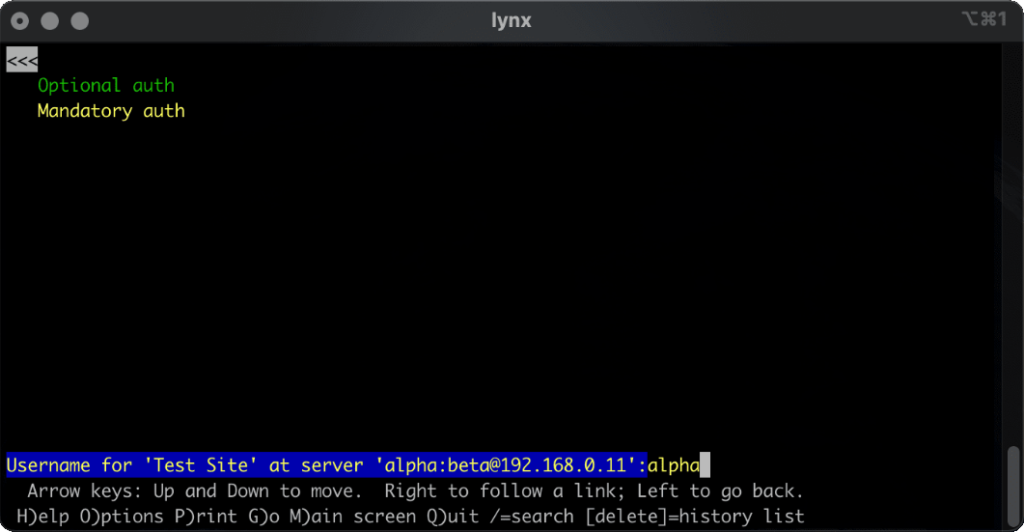

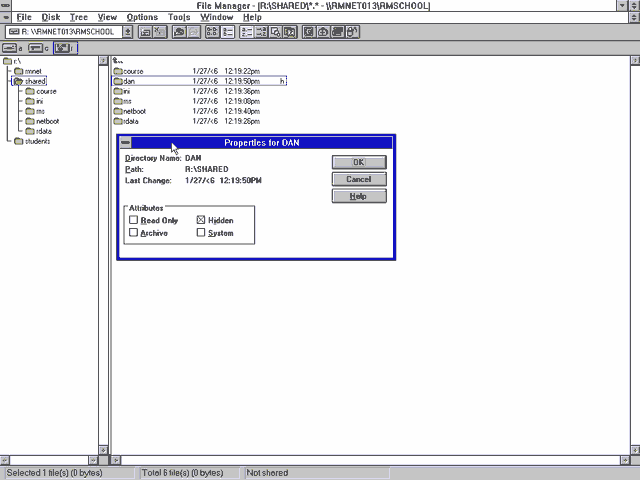

File Manager

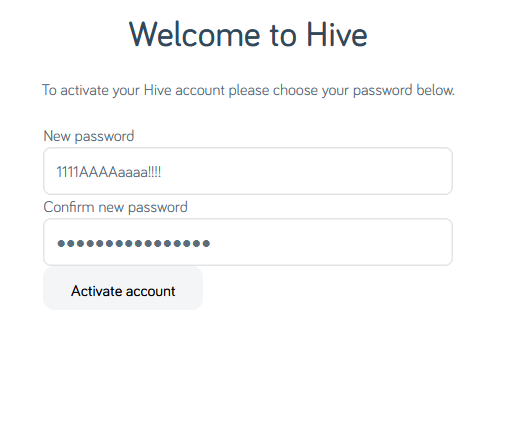

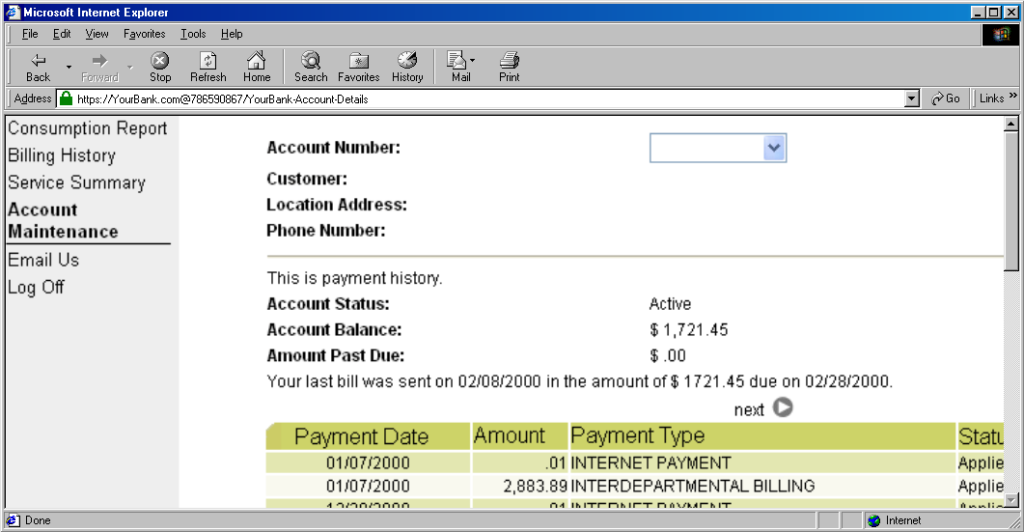

I started to explore the resources on the network. Each pupil had their own networked storage space, but couldn’t access one another’s. But among the directories shared between all students, I found a directory to which I had read-write access.

I created myself a subdirectory and set the hidden bit on it, and started dumping into it things that I wanted to keep on the network8.

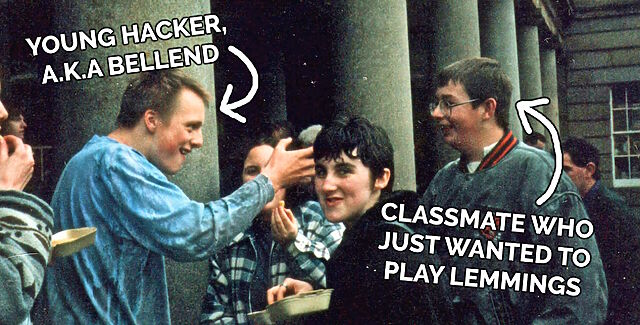

By now my classmates were interested in what I was achieving, and I wanted in the benefits of my success. So I went back to Word and made a document template that looked superficially like a piece of coursework, but which contained macro code that would connect to the shared network drive and allow the user to select from a series of programs that they’d like to run.

Gradually, compressed over a series of floppy disks, I brought in a handful of games: Commander Keen, Prince of Persia, Wing Commander, Civilization, Wolfenstein 3D, even Dune II. I got increasingly proficient at modding games to strip out unnecessary content, e.g. the sound and music files9, minimising the number of floppy disks I needed to ZIP (or ARJ!) content to before smuggling it in via my shirt pocket, always sure not to be carrying so many floppies that it’d look suspicious.

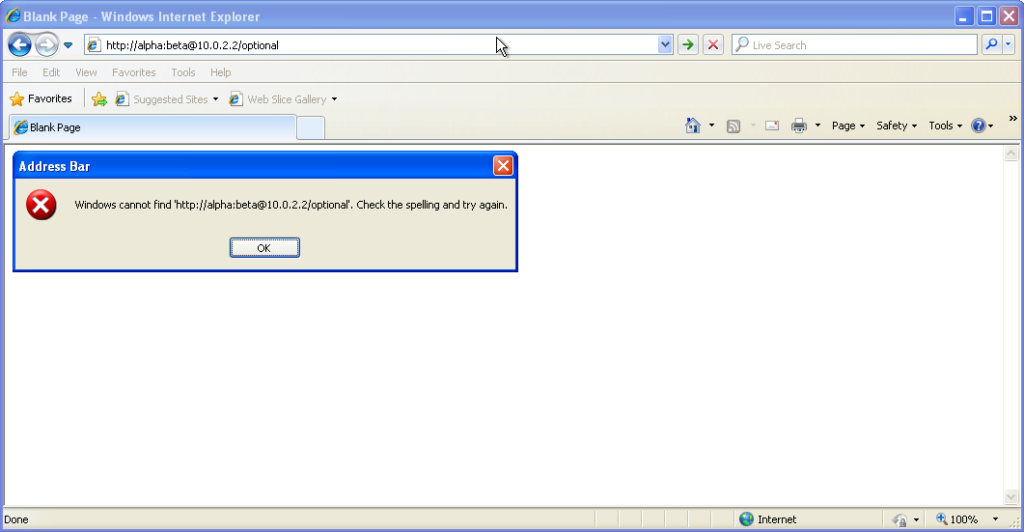

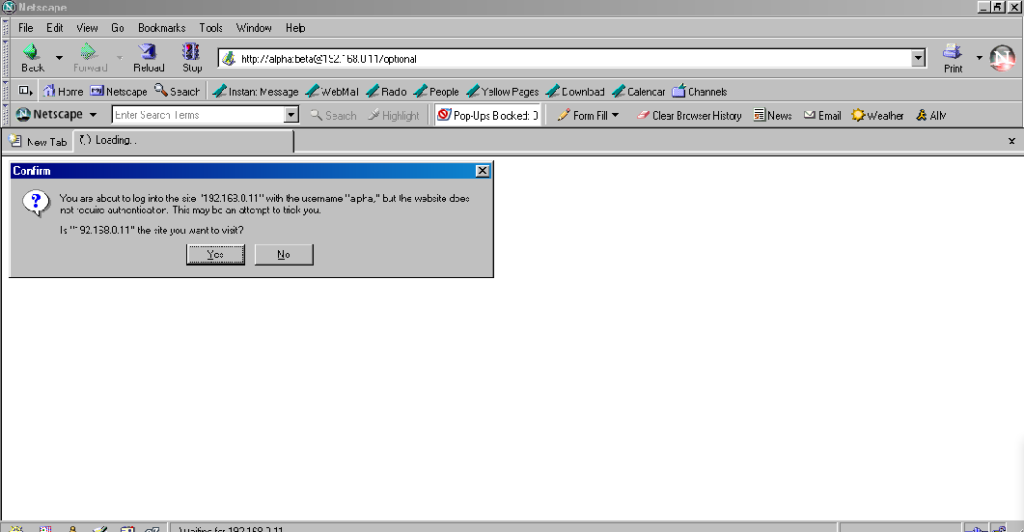

In a particularly bold move, I implemented a simulated login screen which wrote the entered credentials into the shared space before crashing the computer. I left it running, unattended, on computers that I thought most-likely to be used by school staff, and eventually bagged myself the network administrator’s password. I only used it twice: the first time, to validate my hypothesis about the access levels it granted; the second, right before I finished school, to confirm my suspicion that it wouldn’t have been changed during my entire time there10.

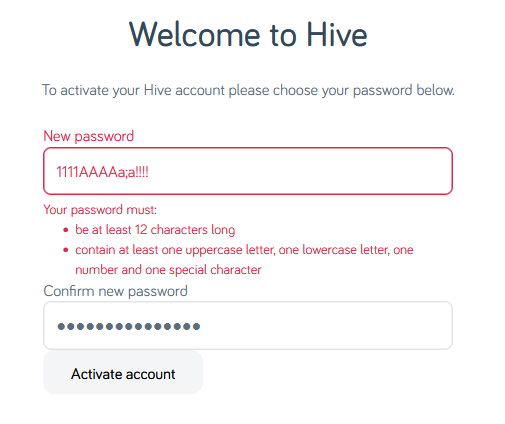

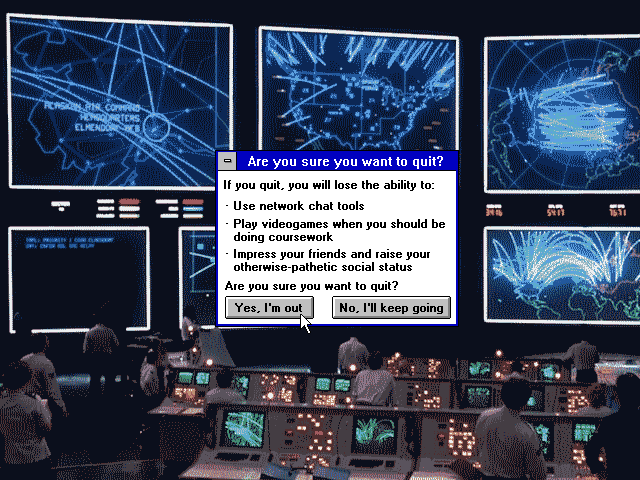

Are you sure you want to quit?

My single biggest mistake was sharing my new-found power with my classmates. When I made that Word template that let others run the software I’d introduced to the network, the game changed.

When it was just me, asking the question what can I make it do?, everything was fun and exciting.

But now half a dozen other teens were nagging me and asking “can you make it do X?”

This wasn’t exploration. This wasn’t innovation. This wasn’t using my curiosity to push at the edges of a system and its restrictions! I didn’t want to find the exploitable boundaries of computer systems so I could help make it easier for other people to do so… no: I wanted the challenge of finding more (and weirder) exploits!

I wanted out. But I didn’t want to say to my friends that I didn’t want to do something “for” them any more11.

I figured: I needed to get “caught”.

I chose… to get sloppy.

I took a copy of some of the software that I’d put onto the shared network drive and put it in my own home directory, this time un-hidden. Clearly our teacher was already suspicious and investigating, because within a few days, this was all that was needed for me to get caught and disciplined13.

I was disappointed not to be asked how I did it, because I was sufficiently proud of my approach that I’d hoped to be able to brag about it to somebody who’d understand… but I guess our teacher just wanted to brush it under the carpet and move on.

Aftermath

The school’s IT admin certainly never worked-out the true scope of my work. My “hidden” files remained undiscovered, and my friends were able to continue to use my special Word template to play games that I’d introduced to the network14. I checked, and the hidden files were still there when I graduated.

The warning worked: I kept my nose clean in computing classes for the remainder of secondary school. But I would’ve been happy to, anyway: I already felt like I’d “solved” the challenge of turning the school computer network to my interests and by now I’d moved on to other things… learning how to reverse-engineer phone networks… and credit card processors… and copy-protection systems. Oh, the stories I could tell15.

But I’ll tell you what: 13-ish year-old me ought to be grateful to the RM Nimbus network at my school for providing an interesting system about which my developing “hacker brain” could ask: what can I make it do?

Which remains one of the most useful questions with which to foster a hacker mentality.

Footnotes

1 I first played Game of Life on an Amstrad CPC464, or possibly a PC1512.

2 What is the earliest experience to which I can credit my “hacker mindset”? Tron and WarGames might have played a part, as might have the “hacking” sequence in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. And there was the videogame Hacker and its sequel (it’s funny to see their influence in modern games). Teaching myself to program so that I could make text-based adventures was another. Dissecting countless obfuscated systems to see how they worked… that’s yet another one: something I did perhaps initially to cheat at games by poking their memory addresses or hexediting their save games… before I moved onto reverse-engineering copy protection systems and working out how they could be circumvented… and then later still when I began building hardware that made it possible for me to run interesting experiments on telephone networks.

Any of all of these datapoints, which took place over a decade, could be interpreted as “the moment” that I became a hacker! But they’re not the ones I’m talking about today. Today… is the story of the RM Nimbus.

3 Whatever happened to Recorder? After it disappeared in Windows 95 I occasionally had occasion to think to myself “hey, this would be easier if I could just have the computer watch me and copy what I do a few times.” But it was not to be: Microsoft decided that this level of easy automation wasn’t for everyday folks. Strangely, it wasn’t long after Microsoft dropped macro recording as a standard OS feature that Apple decided that MacOS did need a feature like this. Clearly it’s still got value as a concept!

4 Just to clarify: I put more effort in to making animations, which were not part of my schoolwork back when I was a kid. I certainly didn’t put more effort into my education.

5 The computers had been configured to make DOS access challenging: a boot menu let you select between DOS and Windows, but both were effectively nerfed. Booting into DOS loaded an RM-provided menu that couldn’t be killed; the MS-DOS prompt icon was absent from Program Manager and quitting Windows triggered an immediate shutdown.

6 My secondary school didn’t get Internet access during the time I was enrolled there. I was recently trying to explain to one of my kids the difference between “being on a network” and “having Internet access”, and how often I found myself on a network that wasn’t internetworked, back in the day. I fear they didn’t get it.

7 I was in the habit of occasionally hooking up PCs together with null modem cables, but only much later on would I end up acquiring sufficient “thinnet” 10BASE2 kit that I could throw together a network for a LAN party.

8 Initially I was looking to sidestep the space limitation enforcement on my “home” directory, and also to put the illicit software I was bringing in somewhere that could not be trivially-easily traced back to me! But later on this “shared” directory became the repository from which I’d distribute software to my friends, too.

9 The school computer didn’t have soundcards and nobody would have wanted PC speakers beeping away in the classroom while they were trying to play a clandestine videogame anyway.

10 The admin password was concepts. For at least four years.

11 Please remember that at this point I was a young teenager and so was pretty well over-fixated on what my peers thought of me! A big part of the persona I presented was of somebody who didn’t care what others thought of him, I’m sure, but a mask that doesn’t look like a mask… is still a mask. But yeah: I had a shortage of self-confidence and didn’t feel able to say no.

12 Art is weird when your medium is software.

13 I was briefly alarmed when there was talk of banning me from the computer lab for the remainder of my time at secondary school, which scared me because I was by now half-way through my boring childhood “life plan” to become a computer programmer by what seemed to be the appropriate route, and I feared that not being able to do a GCSE in a CS-adjacent subject could jeopardise that (it wouldn’t have).

14 That is, at least, my friends who were brave enough to carry on doing so after the teacher publicly (but inaccurately) described my alleged offences, seemingly as a warning to others.

15 Oh, the stories I probably shouldn’t tell! But here’s a teaser: when I built my first “beige box” (analogue phone tap hardware) I experimented with tapping into the phone line at my dad’s house from the outside. I carefully shaved off some of the outer insulation of the phone line that snaked down the wall from the telegraph pole and into the house through the wall to expose the wires inside, identified each, and then croc-clipped my box onto it and was delighted to discovered that I could make and receive calls “for” the house. And then, just out of curiosity to see what kinds of protections were in place to prevent short-circuiting, I experimented with introducing one to the ringer line… and took out all the phones on the street. Presumably I threw a circuit breaker in the roadside utility cabinet. Anyway, I patched-up my damage and – fearing that my dad would be furious on his return at the non-functioning telecomms – walked to the nearest functioning payphone to call the operator and claim that the phone had stopped working and I had no idea why. It was fixed within three hours. Phew!