This week, I spent two days on a shoestring Internet connection, and it was pretty shit.

As you might anticipate, we run a complicated network at our house, and so when my connection dropped a quarter of an hour into the beginning of three and a half hours of scheduled meetings on a busy afternoon, my first thought was to check that everything was working locally. Internal traffic all seemed to be going the right way, so then I checked the primary router and discovered that the problem was further upstream. I checked our fibre terminator, and sure enough: it said it wasn’t getting a signal.

I checked the status page for our ISP – no reported problems. So I called them up. I was pleased that (after I relayed what tests I’d done so far) they treated me like a network specialist rather than somebody who needed hand-holding and we skipped over the usual “have you tried turning it off and on again” and got straight to some diagnosis and scheduling an engineer for the next day. That’d do.

The end of a workday being ruined was a bit of a drag, but for Ruth it was definitely worse, as she was overseeing a major project the following morning (from 5am!) and so needed to arrange for emergency out-of-hours access to her office for the next day to be able to make it work. As for me: I figured I’d be back online by lunchtime, and working a little into the evening would give me a rare opportunity for an increased overlap with my team – many of which are on the Pacific coast of the US – so it’d all work out.

The engineer arrived the next morning, just as a storm hit. He traced the problem, waited for the rain to ease off, then stomped off up the street to get it fixed. Only a matter of time now, I thought.

But nope: he came back to say that wherever the fault had occurred was found somewhere under the road that he couldn’t access by himself: it’d need a team of two engineers to get down there and fix it, and they wouldn’t be able to come… until tomorrow.

So I went up to the attic to work, which is just about the only place in the house where – by balancing my phone against a window – I can consistently tether at 4G/5G. Well… semi-consistently. Inconsistently enough to be immensely frustrating.

There’s this thing, I find: no Internet access is annoying, but tolerable.

Slow Internet access is similar.

But intermittent Internet access is, somehow, a nightmare. Applications hang or fail in unpredictable ways, their developers not having planned for the possibility that the

connection they detected for when they were opened might come and go at random. Shitty modern “web applications” that expect to download multiple megabytes of JavaScript before they

work show skeleton loaders and dehydrated <div>s that might one day grow up to be something approximating a button, link, or image. It’s just generally a pretty crap

experience.

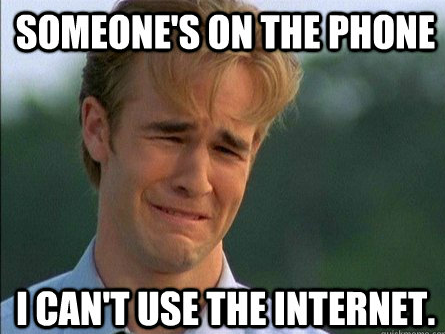

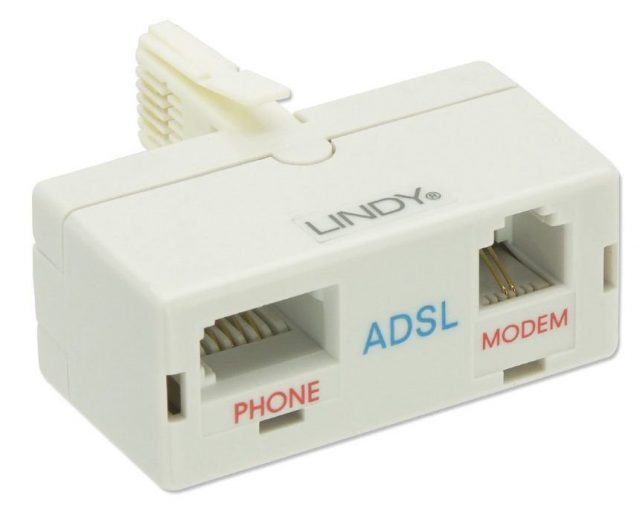

It’s funny how we got so dependent upon the Internet. 26+ years ago, I used to write most of my Web-destined PHP and Perl code “offline”! I’d dial-up to the Internet to download documentation or upload code, then work from my memory, from books, and what I’d saved from the Web. Can you imagine asking a junior Web developer to do that today?

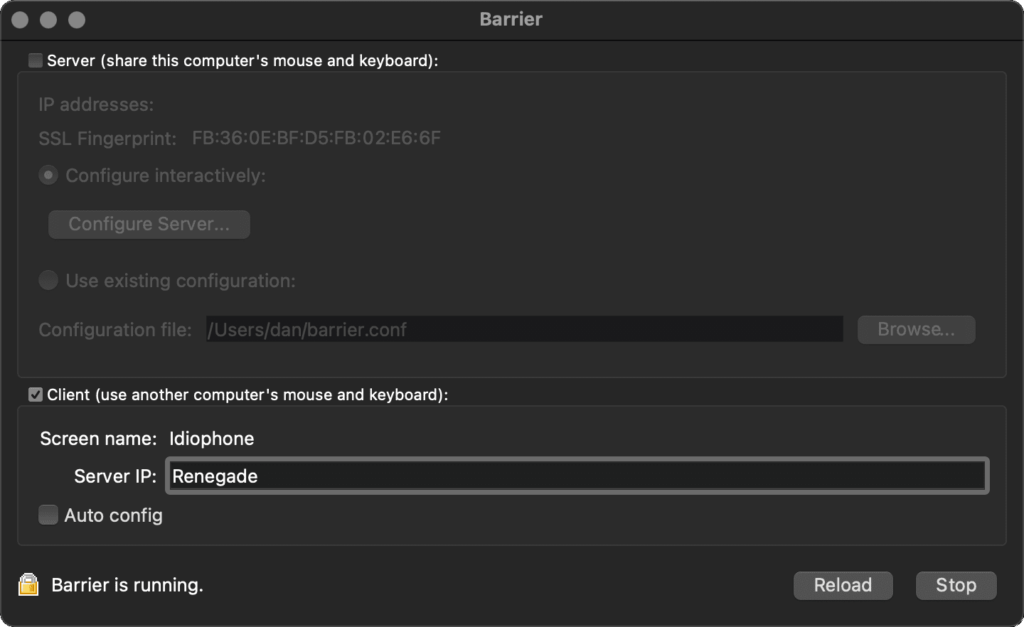

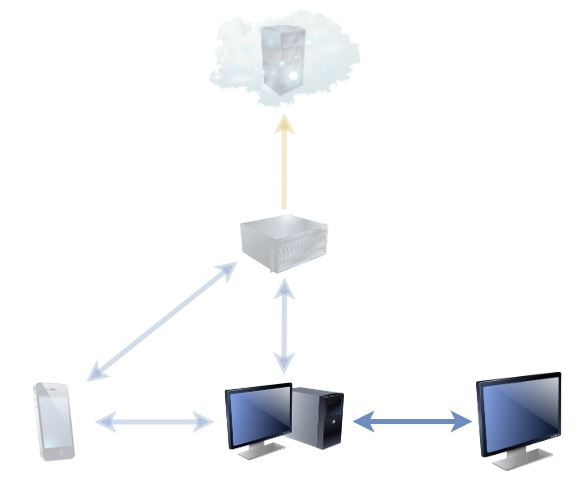

In a second ironic twist, a parcel arrived for me during our downtime which contained new network hardware with which I planned to eliminate a couple of WiFi weak spots at the edges of our house. The new hardware worked perfectly and provided a wonderful improvement to signal strength between our computers… but of course not to computers outside of the network.

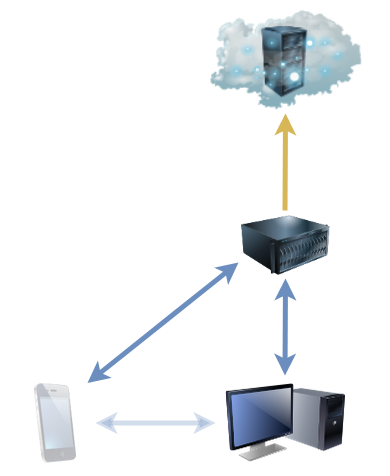

There’s another interesting thing that’s changed over the decades. When I first started installing (bus!) networks, there was no assumption that the network would necessarily provide Internet access. The principal purpose of the network was to connect the computers within the LAN to one another. This meant that staff could access one another’s files more easily and make use of a shared printer without walking around carrying floppy disks, for example… or could frag one another at Doom and Quake at the LAN parties that I’d sometimes run from my mum’s living room!

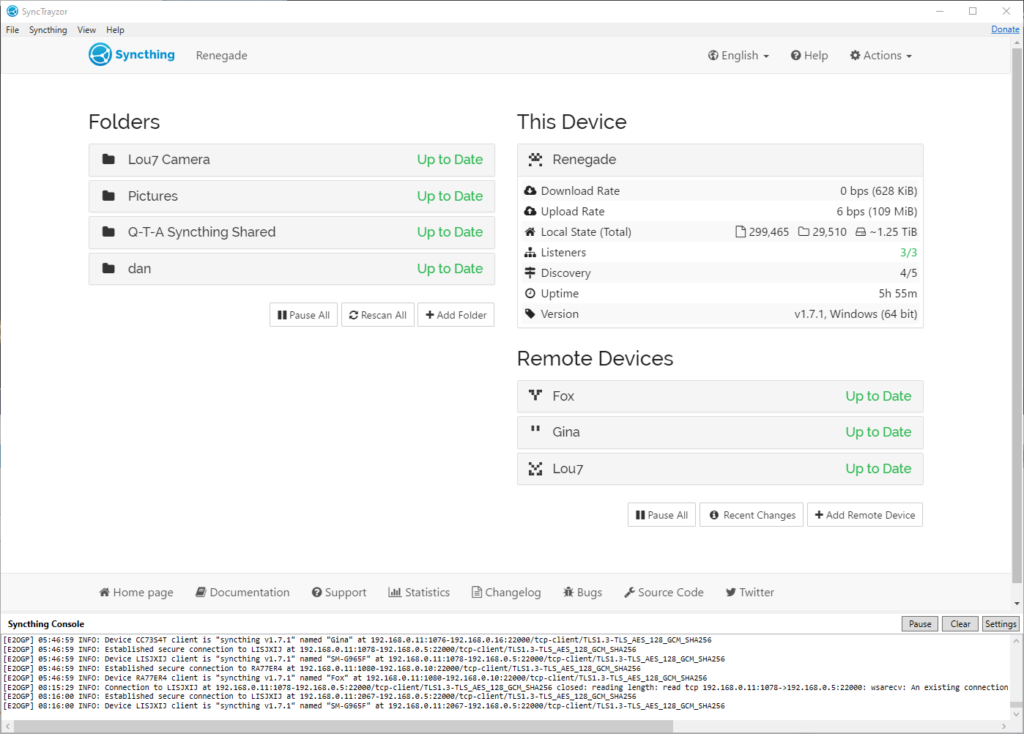

But nowadays, if you connect to a network (whether wired or wireless) there’s an expectation that it’ll provide Internet access. So much so, that if you join a wireless network using your mobile phone and it doesn’t provide Internet access, your phone probably won’t route any traffic across it unless you specifically say that it should. That’s a reasonable default, these days, but it’s an annoyance when – for example – I wanted my phone to continue using Syncthing to back up my photos to my NAS even though the network that my NAS was on would no longer provide Internet access to my phone!

The second team of engineers quickly found and repaired a break in the fibre – apparently it was easier than the first engineer had expected – and normalcy returned to our household.

But for a couple of days, there, I was forcibly (and unpleasantly) reminded about how the world has changed since the time that “being on a network” wasn’t assumed to be synonymous with “has Internet access”.

![Stylish (for circa 2000) webpage for HoTMetaL Pro 6.0, advertising its 'unrivaled [sic] editing, site management and publishing tools'.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2025/08/hotmetal-pro-6-640x396.jpg)