Made it through a day and a half of theme park fun with the kids. Time for a much-needed beer, then as long a sleep as circumstance will allow.

Tag: holiday

Dos Huevos

Hackaday

Melià Barcelona Sky

Note #24813

Freedom of the Mountain

During a family holiday last week to the Three Valleys region of the French Alps for some skiing1, I came to see that I enjoy a privilege I call the freedom of the mountain.

The Freedom

The freedom of the mountain is a privilege that comes from having the level of experience necessary to take on virtually any run a resort has to offer. It provides a handful of benefits denied to less-confident skiers:

- I usually don’t feed to look at a map to plan my next route; whichever way I go will be fine!

- When I reach one or more lifts, I can choose which to take based on the length of their queue, rather than considering their destinations.

- When faced with a choice of pistes (or an off-piste route), my choice can be based on my mood, how crowded they are, etc., rather than their rated difficulty.

The downside is that I’m less well-equipped to consider the needs of others! Out skiing with Ruth one morning I suggested a route back into town that “felt easy” based on my previous runs, only to have her tell me that – according to the map – it probably wasn’t!

Approaching the Peak

The kids spent the week in lessons. It’s paying off: they’re both improving fast, and the eldest has got all the essentials down and it’s working on improving her parallel turns and on “reading the mountain”. It’s absolutely possible that the eldest, and perhaps both of them, will be a better skier than me someday2.

Maybe, as part of my effort to do what I’m bad at, I should have another go at learning to snowboard. I always found snowboarding frustrating because everything I needed to re-learn was something that I could already do much better and easier on skis. But perhaps if I can reframe that frustration through the lens of learning itself as the destination, I might be in a better place. One to consider for next time I hit the piste.

Footnotes

1 Also a little geocaching and some mountainside Where’s Wally?

2 Assuming snow is still a thing in ten years time.

Short-Term Blogging

There’s a perception that a blog is a long-lived, ongoing thing. That it lives with and alongside its author.1

But that doesn’t have to be true, and I think a lot of people could benefit from “short-term” blogging. Consider:

-

Photoblogging your holiday, rather than posting snaps to social media

You gain the ability to add context, crosslinking, and have permanent addresses (rather than losing eveything to the depths of a feed). You can crosspost/syndicate to your favourite socials if that’s your poison..

-

Blogging your studies, rather than keeping your notes to yourself

Writing what you learn helps you remember it; writing what you learn in a public space helps others learn too and makes it easy to search for your discoveries later.2 -

Recording your roleplaying, rather than just summarising each session to your fellow players

My D&D group does this at levellers.blog! That site won’t continue to be updated forever – the party will someday retire or, more-likely, come to a glorious but horrific end – but it’ll always live on as a reminder of what we achieved.

One of my favourite examples of such a blog was 52 Reflect3 (now integrated into its successor The Improbable Blog). For 52 consecutive weeks my partner‘s brother Robin blogged about adventures that took him out of his home in London and it was amazing. The project’s finished, but a blog was absolutely the right medium for it because now it’s got a “forever home” on the Web (imagine if he’d posted instead to Twitter, only for that platform to turn into a flaming turd).

I don’t often shill for my employer, but I genuinely believe that the free tier on WordPress.com is an excellent way to give a forever home to your short-term blog4. Did you know that you can type new.blog (or blog.new; both work!) into your browser to start one?

What are you going to write about?

Footnotes

1 This blog is, of course, an example of a long-term blog. It’s been going in some form or another for over half my life, and I don’t see that changing. But it’s not the only kind of blog.

2 Personally, I really love the serendipity of asking a web search engine for the solution to a problem and finding a result that turns out to be something that I myself wrote, long ago!

3 My previous posts about 52 Reflect: Challenge Robin, Twatt, Brixton to Brighton by Boris Bike, Ending on a High (and associated photo/note)

4 One of my favourite features of WordPress.com is the fact that it’s built atop the world’s most-popular blogging software and you can export all your data at any time, so there’s absolutely no lock-in: if you want to migrate to a competitor or even host your own blog, it’s really easy to do so!

Holidays in the Age of COVID

We’ve missed out on or delayed a number of trips and holidays over the last year and a half for, you know, pandemic-related reasons. So this summer, in addition to our trip to Lichfield, we arranged a series of back-to-back expeditions.

1. Alton Towers

The first leg of our holiday saw us spend a long weekend at Alton Towers, staying over at one of their themed hotels in between days at the water park and theme park:

2. Darwin Forest

The second leg of our holiday took us to a log cabin in the Darwin Forest Country Park for a week:

3. Preston

Kicking off the second week of our holiday, we crossed the Pennines to Preston to hang out with my family (with the exception of JTA, who had work to do back in Oxfordshire that he needed to return to):

4. Forest of Bowland

Ruth and I then left the kids with my mother and sisters for a few days to take an “anniversary mini-break” of glamping in the gorgeous Forest of Bowland:

(If you’re interested in Steve Taylor’s bathtub-carrying virtual-Everest expedition, here’s his Facebook page and JustGiving profile.)

5. Meanwhile, in Preston

The children, back in Preston, were apparently having a whale of a time:

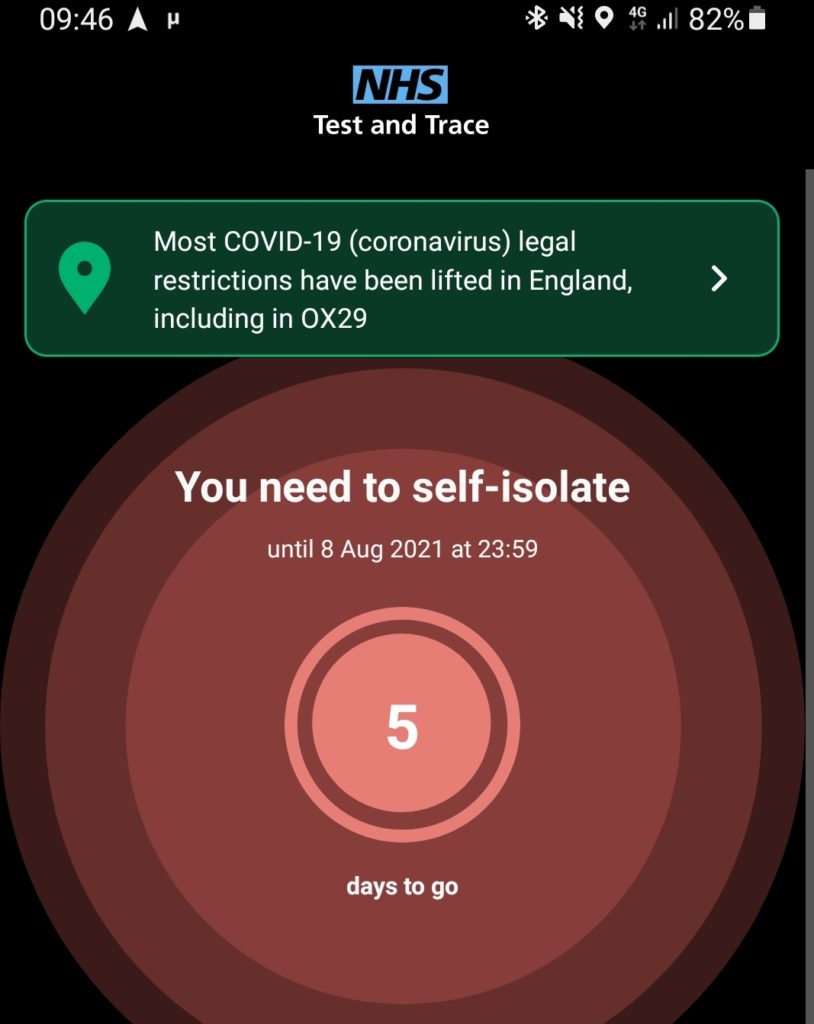

6. Suddenly, A Ping

The plan from this point was simple: Ruth and I would return to Preston for a few days, hang out with my family some more, and eventually make a leisurely return to Oxfordshire. But it wasn’t to be…

I got a “ping”. What that means is that my phone was in close proximity to somebody else’s phone on 29 August and that other person subsequently tested positive for COVID-19.

My risk from this contact is exceptionally low. There’s only one place that my phone was in close proximity to the phone of anybody else outside of my immediate family, that day, and it’s when I left it in a locker at the swimming pool near our cabin in the Darwin Forest. Also, of course, I’d been double-jabbed for a month and a half and I’m more-cautious than most about contact, distance, mask usage etc. But my family are, for their own (good) reasons, more-cautious still, so self-isolating at Preston didn’t look like a possibility for us.

As soon as I got the notification we redirected to the nearest testing facility and both got swabs done. 8 days after possible exposure we ought to have a detectable viral load, if we’ve been infected. But, of course, the tests take a day or so to process, so we still needed to do a socially-distanced pickup of the kids and all their stuff from Preston and turn tail for Oxfordshire immediately, cutting our trip short.

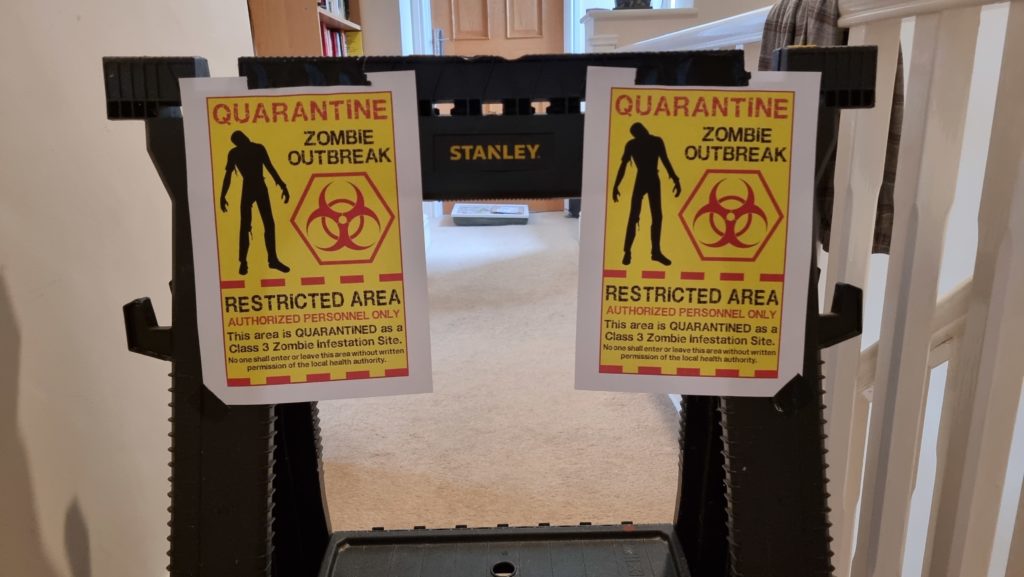

The results would turn up negative, and subsequent tests would confirm that the “ping” was a false positive. And in an ironic twist, heading straight home actually put us closer to an actual COVID case as Ruth’s brother Owen turned out to have contracted the bug at almost exactly the same time and had, while we’d been travelling down the motorway, been working on isolating himself in an annex of the “North wing” of our house for the duration of his quarantine.

7. Ruth & JTA go to Berwick

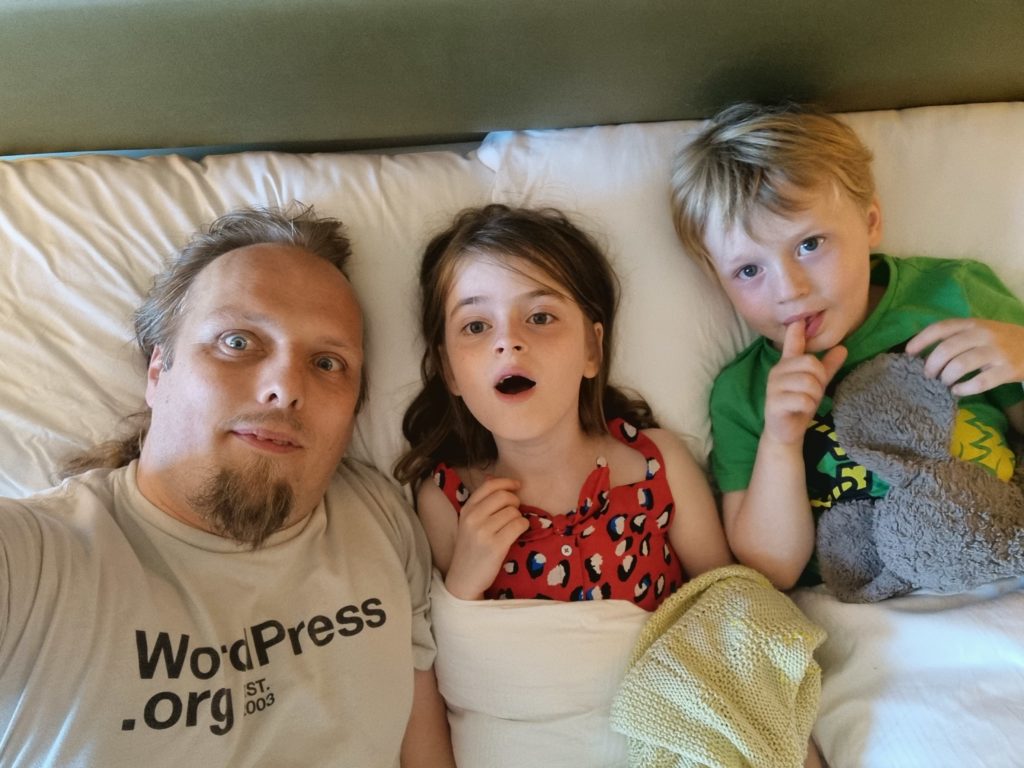

Thanks to negative tests and quick action in quarantining Owen, Ruth and JTA were still able to undertake the next part of this three-week holiday period and take their anniversary break (which technically should be later in the year, but who knows what the situation will be by then?) to Berwick-upon-Tweed. That’s their story to tell, if they want to, but the kids and I had fun in their absence:

8. Reunited again

Finally, Ruth and JTA returned from their mini-break and we got to do a few things together as a family again before our extended holiday drew to a close:

9. Back to work?

Tomorrow I’m back at work, and after 23 days “off” I’m honestly not sure I remember what I do for a living any more. Something to do with the Internet, right? Maybe ecommerce?

I’m sure it’ll all come right back to me, at least by the time I’ve read through all the messages and notifications that doubtless await me (I’ve been especially good at the discipline, this break, of not looking at work notifications while I’ve been on holiday; I’m pretty proud of myself.)

But looking back, it’s been a hell of a three weeks. After a year and a half of being pretty-well confined to one place, doing a “grand tour” of so many destinations as a family and getting to do so many new and exciting things has made the break feel even longer than it was. It seems like it must have been months since I last had a Zoom meeting with a work colleague!

For now, though, it’s time to try to get the old brain back into work mode and get back to making the Web a better place!

Dan Q found GC1HW0N Penhul Hyll

This checkin to GC1HW0N Penhul Hyll reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

My partner fleeblewidget and I are celebrating 14 years together as a couple with a glamping holiday near Sawley and took the opportunity to climb up Pendle Hill this morning. I’ve many fond memories of taking this route with my father, when he was alive, and it’s interesting to be able to see how, just on the timescales of my own life, the shape of this hillside has changed owing to smaller landslides. Lower down, for example, human-caused erosion (picture attached) has damaged our destroyed paths I used to take, and new fences encourage climbers onto alternative routes. We also observed evidence (picture attached) of an older landslide, with a cliff of relatively new earth exposed where there clearly used to be a grassy/rocky slope.

Views were very good today and we could just about make out what we assume is the Ribble estuary in the distance from near the summit. A great and enjoyable expedition. Picture of the two of us at the trig point attached. TFTC.

Dan Q found GC56V1D U P 6

This checkin to GC56V1D U P 6 reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

My partner fleeblewidget and I are glamping up near Sawley to celebrate our 14th anniversary and came out today for a walk up Pendle Hill. Cache container was in the third place we looked; a nice easy find! Log a little damp but usable. TFTC.

Dan Q found GC46ZR0 B-by-B 3 feet and rising

This checkin to GC46ZR0 B-by-B 3 feet and rising reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

My partner fleeblewidget and I are staying at nearby Calder Farm to celebrate our anniversary and took a walk this afternoon to find this cache. Only around 300m as the crow flies from the GZ we figured this would be a quick expedition, but there’s no convenient path down to the riverside from where we are. Our first attempt at an approach took us to the North end of the footpath, but this seems to be through a garden centre/nursery that’s closed, and we couldn’t confirm whether or not the public footpath was open “through” or despite this, so we doubled go past our accommodation and approached from the South instead, ultimately resulting in a ~2km walk to and from the GZ!

Coordinates seemed off by about 5m based on my GPSr and phone, but the hint pointed us towards the obvious candidate and the cache was easily visible (although a bit of a stretch to reach!). Log had been inserted deep into the tube rather than the lid of the container and we struggled to extract it but got there in the end (we put it back in the lid for the benefit of the next cacher). TFTC.

Dan Q found GC1Y6GZ One Giant Step

This checkin to GC1Y6GZ One Giant Step reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Greetings from Oxfordshire! I’m staying in the holiday park just East of here as part of the first of a three week holiday (taken in an attempt to “make up” for holidays cancelled over the last year and a half owing to The Situation). I figured it’d be an easy and relatively direct hike from there to here, but I’d not counted on the work underway at the moment by the Forestry Commission! Several diverted footpaths later I finally found this “giant step”! Took Paul the Seahorse TB, SL, TFTC.

Lichfield

We took a family trip up to Lichfield this weekend. I don’t know if I can give a “review” of a city-break as a whole, but if I can: I give you five stars, Lichfield.

Maybe it’s just because we’ve none of us had a night away from The Green… pretty-much since we moved in, last year. But there was something magical about doing things reminiscent of the “old normal”.

It’s not that like wasn’t plenty of mask-wearing and social distancing and hand sanitiser and everything that we’ve gotten used to now: there certainly was. The magic, though, came from getting to do an expedition further away from home than we’re used to. And, perhaps, with that happening to coincide with glorious weather and fun times.

We spent an unimaginably hot summer’s day watching an outdoor interpretation of Peter and the Wolf, which each of the little ones has learned about in reasonable depth, at some point or another, as part of the (fantastic) “Monkey Music” classes of which they’re now both graduates.

And maybe it’s that they’ve been out-of-action for so long and are only just beginning to once again ramp up… or maybe I’ve just forgotten what the hospitality industry is like?… but man, we felt well-looked after.

From the staff at the hotel who despite the clear challenges of running their establishment under the necessary restrictions still went the extra mile to make the kids feel special to the restaurant we went to that pulled out all the stops to give us all a great evening, I basically came out of the thing with the impression of Lichfield as a really nice place.

I’m not saying that it was perfect. A combination of the intolerable heat (or else the desiccating effect of the air conditioner) and a mattress that sagged with two adults on it meant that I didn’t sleep much on Saturday night (although that did mean I could get up at 5am for a geocaching expedition around the city before it got too hot later on). And an hour and a half of driving to get to a place where you’re going to see a one-hour show feels long, especially in this age where I don’t really travel anywhere, ever.

But that’s not the point.

The point is that Lichfield made me happy, this weekend. And I don’t know how much of that is that it’s just a nice place and how much is that I’ve missed going anywhere or doing anything, but either way, it lead to a delightful weekend.

Note #14877

Heading back by train from a holiday in Derbyshire with @bornvulcan, @Crusty_Twobags, @fleeblewidget, @TheGodzillaGirl, @LadyJemma_, @Andrewsean85, and others. This trip must have been under some kind of curse: contagious gastric illnesses, dog-bite drama, perpetual rain, and a satnav that directed me to drive down a footpath!

For the benefit of those that suffered alongside me, I’ve started collating pictures and videos here.

Anniversary Break

We might never have been very good at keeping track of the exact date our relationship began in Edinburgh twelve years ago, but that doesn’t stop Ruth and I from celebrating it, often with a trip away very-approximately in the summer. This year, we marked the occasion with a return to Scotland, cycling our way around and between Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Northwards #

Even sharing a lightweight conventional bike and a powerful e-bike, travelling under your own steam makes you pack lightly. We were able to get everything we needed – including packing for the diversity of weather we’d been told to expect – in a couple of pannier bags and a backpack, and pedalled our way down to Oxford Parkway station to start our journey.

In anticipation of our trip and as a gift to me, Ruth had arranged for tickets on the Caledonian Sleeper train from London to Glasgow and returning from Edinburgh to London to bookend our adventure. A previous sleeper train ticket she’d purchased, for Robin as part of Challenge Robin II, had lead to enormous difficulties when the train got cancelled… but how often can sleeper trains get cancelled, anyway?

![Digital display board: "Passengers for the Caledonian Sleeper service tonight departing at 23:30 are being advised that the Glasgow portio [sic] of this service has been cancelled. For further information please see staff on"](/_q23u/2019/06/20190623_222859-1024x498.jpg)

Station staff advised us that instead of a nice fast train full of beds they’d arranged for a grotty slow bus full of disappointment. It took quite a bit of standing-around and waiting to speak to the right people before anybody could even confirm that we’d be able to stow our bikes on the bus, without which our plans would have been completely scuppered. Not a great start!

Eight uncomfortable hours of tedious motorway (and the opportunity to wave at Oxford as we went back past it) and two service stations later, we finally reached Glasgow.

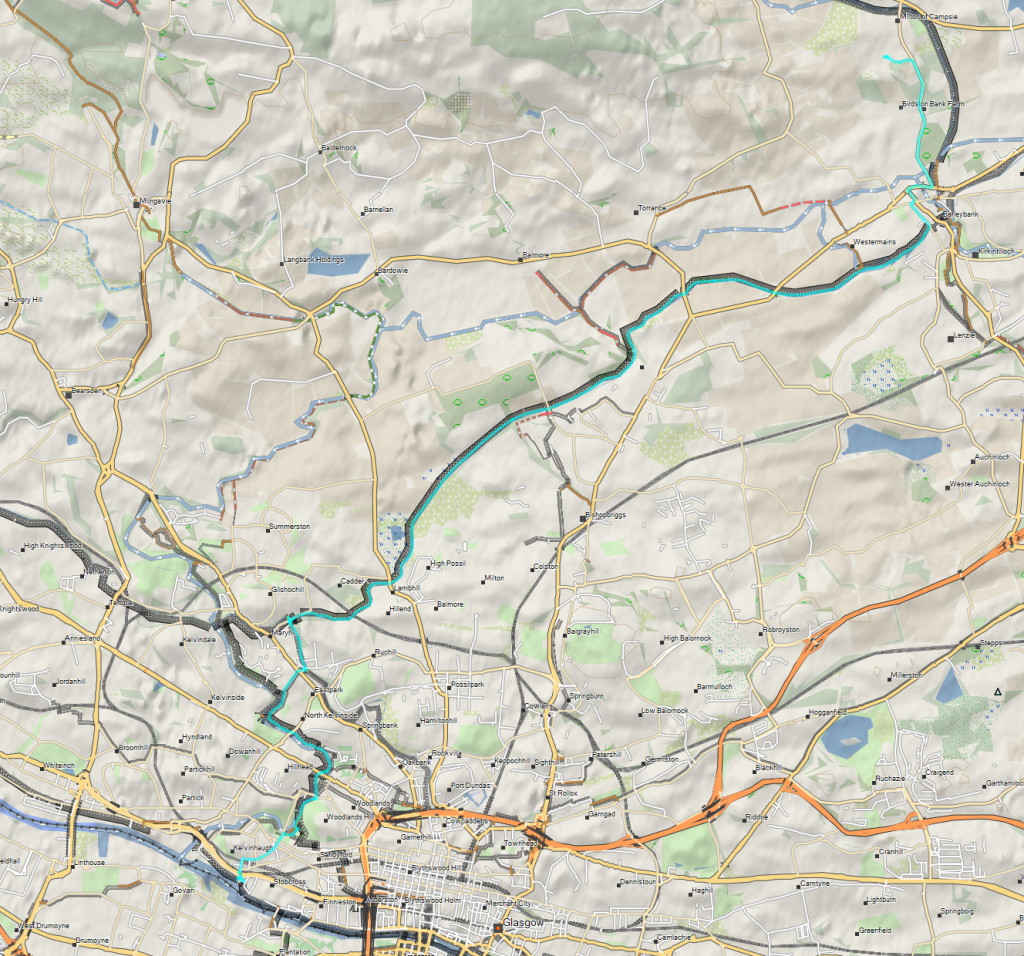

Glasgow #

Despite being tired and in spite of the threatening stormclouds gathering above, we pushed on with our plans to explore Glasgow. We opted to put our trust into random exploration – aided by responses to weirdly-phrased questions to Google Assistant about what we should see or do – to deliver us serendipitous discoveries, and this plan worked well for us. Glasgow’s network of cycle paths and routes seems to be effectively-managed and sprawls across the city, and getting around was incredibly easy (although it’s hilly enough that I found plenty of opportunities to require the lowest gears my bike could offer).

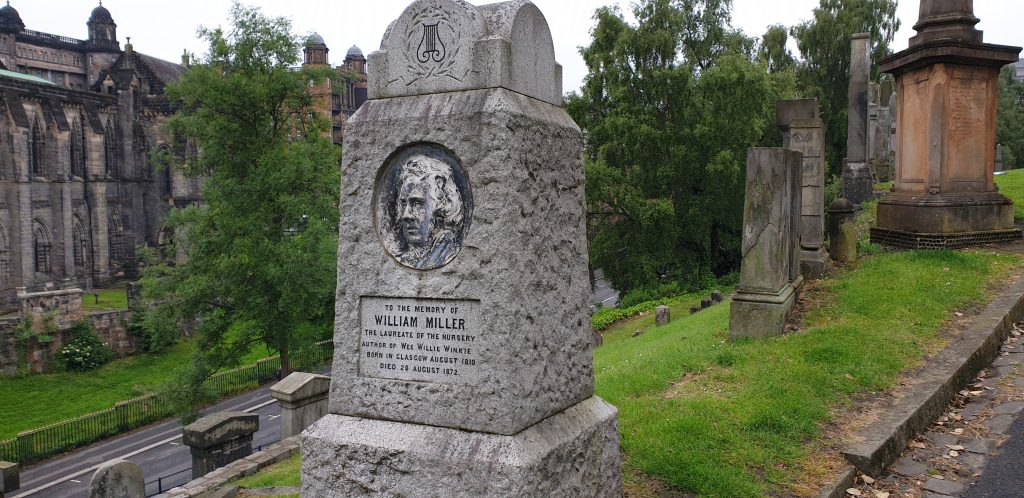

We kicked off by marvelling at the extravagance of the memorials at Glasgow Necropolis, a sprawling 19th-century cemetery covering an entire hill near the city’s cathedral. Especially towards the top of the hill the crypts and monuments give the impression that the dead were competing as to who could leave the most-conspicuous marker behind, but there are gems of subtler and more-attractive Gothic architecture to be seen, too. Finding a convenient nearby geocache completed the experience.

Pushing on, we headed downriver in search of further adventure… and breakfast. The latter was provided by the delightful Meat Up Deli, who make a spectacularly-good omelette. There, in the shadow of Partick Station, Ruth expressed surprise at the prevalence of railway stations in Glasgow; she, like many folks, hadn’t known that Glasgow is served by an underground train network, But I too would get to learn things I hadn’t known about the subway at our next destination.

We visited the Riverside Museum, whose exhibitions are dedicated to the history of transport and industry, with a strong local focus. It’s a terrifically-engaging museum which does a better-than-usual job of bringing history to life through carefully-constructed experiences. We spent much of the time remarking on how much the kids would love it… but then remembering that the fact that we were able to enjoy stopping and read the interpretative signage and not just have to sprint around after the tiny terrors was mostly thanks to their absence! It’s worth visiting twice, if we find ourselves up here in future with the little tykes.

It’s also where I learned something new about the Glasgow Subway: its original implementation – in effect until 1935 – was cable-driven! A steam engine on the South side of the circular network drove a pair of cables – one clockwise, one anticlockwise, each 6½ miles long – around the loop, between the tracks. To start the train, a driver would pull a lever which would cause a clamp to “grab” the continuously-running cable (gently, to prevent jerking forwards!); to stop, he’d release the clamp and apply the brakes. This solution resulted in mechanically-simple subway trains: the system’s similar to that used for some of the surviving parts of San Franciso’s original tram network.

Equally impressive as the Riverside Museum is The Tall Ship accompanying it, comprising the barque Glenlee converted into a floating museum about itself and about the maritime history of its age.

This, again, was an incredibly well-managed bit of culture, with virtually the entire ship accessible to visitors, right down into the hold and engine room, and with a great amount of effort put into producing an engaging experience supported by a mixture of interactive replicas (Ruth particularly enjoyed loading cargo into a hoist, which I’m pretty sure was designed for children), video, audio, historical sets, contemporary accounts, and all the workings of a real, functional sailing vessel.

After lunch at the museum’s cafe, we doubled-back along the dockside to a distillery we’d spotted on the way past. The Clydeside Distillery is a relative newcomer to the world of whisky – starting in 2017, their first casks are still several years’ aging away from being ready for consumption, but that’s not stopping them from performing tours covering the history of their building (it’s an old pumphouse that used to operate the swingbridge over the now-filled-in Queen’s Dock) and distillery, cumulating in a whisky tasting session (although not yet including their own single malt, of course).

This was the first time Ruth and I had attended a professionally-organised whisky-tasting together since 2012, when we did so not once but twice in the same week. Fortunately, it turns out that we hadn’t forgotten how to drink whisky; we’d both kept our hand in in the meantime. <hic> Oh, and we got to keep our tasting-glasses as souvenirs, which was a nice touch.

Forth & Clyde Canal #

Thus far we’d been lucky that the rain had mostly held-off, at least while we’d been outdoors. But as we wrapped up in Glasgow and began our cycle ride down the towpath of the Forth & Clyde Canal, the weather turned quickly through bleak to ugly to downright atrocious. The amber flood warning we’d been given gave way to what forecasters and the media called a “weather bomb”: an hours-long torrential downpour that limited visibility and soaked everything left out in it.

You know: things like us.

Our bags held up against the storm, thankfully, but despite an allegedly-waterproof covering Ruth and I both got thoroughly drenched. By the time we reached our destination of Kincaid House Hotel we were both exhausted (not helped by a lack of sleep the previous night during our rail-replacement-bus journey) and soaking wet right through to our skin. My boots squelched with every step as we shuffled uncomfortably like drowned rats into a hotel foyer way too-fancy for bedraggled waifs like us.

We didn’t even have the energy to make it down to dinner, instead having room service delivered to the room while we took turns at warming up with the help of a piping hot bath. If I can sing the praises of Kincaid House in just one way, though, it’s that the food provided by room service was absolutely on-par with what I’d expect from their restaurant: none of the half-hearted approach I’ve experienced elsewhere to guests who happen to be too knackered (and in my case: lacking appropriate footwear that’s not filled with water) to drag themselves to a meal.

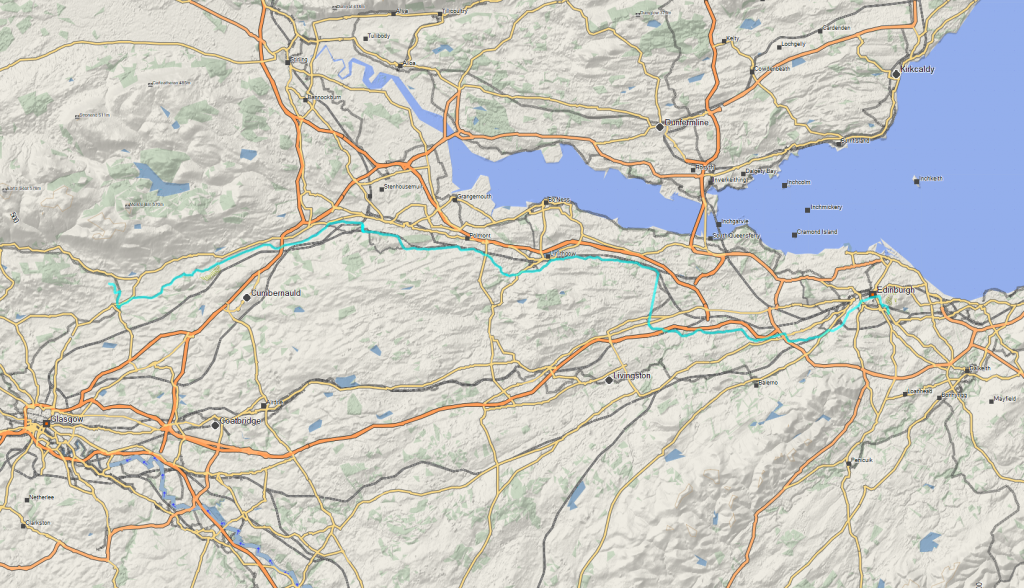

Our second day of cycling was to be our longest, covering the 87½ km (54½ mile) stretch of riverside and towpath between Milton of Campsie and our next night’s accommodation on the South side of Edinburgh. We were wonderfully relieved to discover that the previous day’s epic dump of rain had used-up the clouds’ supply in a single day and the forecast was far more agreeable: cycling 55 miles during a downpour did not sound like a fun idea for either of us!

Kicking off by following the Strathkelvin Railway Path, Ruth and I were able to enjoy verdant countryside alongside a beautiful brook. The signs of the area’s industrial past are increasingly well-concealed – a rotting fence made of old railway sleepers here; the remains of a long-dead stone bridge there – and nature has reclaimed the land dividing this former-railway-now-cycleway from the farmland surrounding it. Stopping briefly for another geocache we made good progress down to Barleybank where we were able to rejoin the canal towpath.

This is where we began to appreciate the real beauty of the Scottish lowlands. I’m a big fan of a mountain, but there’s also a real charm to the rolling wet countryside of the Lanarkshire valleys. The Forth & Clyde towpath is wonderfully maintained – perhaps even better than the canal itself, which is suffering in patches from a bloom of spring reeds – and makes for easy cycling.

Outside of moorings at the odd village we’d pass, we saw no boats along most of the inland parts of the Forth & Clyde canal. We didn’t see many joggers, or dog-walkers, or indeed anybody for long stretches.

The canal was also teeming with wildlife. We had to circumnavigate a swarm of frogs, spotted varied waterfowl including a heron who’d decided that atop a footbridge was the perfect place to stand and a siskin that made itself scarce as soon as it spotted us, and saw evidence of water voles in the vicinity. The rushes and woodland all around but especially on the non-towpath side of the canal seemed especially popular with the local fauna as a place broadly left alone by humans.

The canal meanders peacefully, flat and lock-free, around the contours of the Kelvin valley all the way up to the end of the river. There, it drops through Wyndford Lock into the valley of Bonny Water, from which the rivers flow into the Forth. From a hydrogeological perspective, this is the half-way point between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Seven years ago, I got the chance to visit the Falkirk Wheel, but Ruth had never been so we took the opportunity to visit again. The Wheel is a very unusual design of boat lift: a pair of counterbalanced rotating arms swap places to move entire sections of the canal from the lower to upper level, and vice-versa. It’s significantly faster to navigate than a flight of locks (indeed, there used to be a massive flight of eleven locks a little way to the East, until they were filled in and replaced with parts of the Wester Hailes estate of Falkirk), wastes no water, and – because it’s always in a state of balance – uses next to no energy to operate: the hydraulics which push it oppose only air resistance and friction.

So naturally, we took a boat ride up and down the wheel, recharged our batteries (metaphorically; the e-bike’s battery would get a top-up later in the day) at the visitor centre cafe, and enjoyed listening-in to conversations to hear the “oh, I get it” moments of people – mostly from parts of the world without a significant operating canal network, in their defence – learning how a pound lock works for the first time. It’s a “lucky 10,000” thing.

Pressing on, we cycled up the hill. We felt a bit cheated, given that we’d just been up and down pedal-free on the boat tour, and this back-and-forth manoeuvrer confused my GPSr – which was already having difficulty with our insistence on sticking to the towpath despite all the road-based “shortcuts” it was suggesting – no end!

Union Canal #

From the top of the Wheel we passed through Rough Castle Tunnel and up onto the towpath of the Union Canal. This took us right underneath the remains of the Antonine Wall, the lesser-known sibling of Hadrian’s Wall and the absolute furthest extent, albeit short-lived, of the Roman Empire on this island. (It only took the Romans eight years to realise that holding back the Caledonian Confederacy was a lot harder work than their replacement plan: giving most of what is now Southern Scotland to the Brythonic Celts and making the defence of the Northern border into their problem.)

A particular joy of this section of waterway was the Falkirk Tunnel, a very long tunnel broad enough that the towpath follows through it, comprised of a mixture of hewn rock and masonry arches and very variable in height (during construction, unstable parts of what would have been the ceiling had to be dug away, making it far roomier than most narrowboat canal tunnels).

Wet, cold, slippery, narrow, and cobblestoned for the benefit of the horses that no-longer pull boats through this passage, we needed to dismount and push our bikes through. This proved especially challenging when we met other cyclists coming in the other direction, especially as our e-bike (as the designated “cargo bike”) was configured in what we came to lovingly call “fat ass” configuration: with pannier bags sticking out widely and awkwardly on both sides.

This is probably the oldest tunnel in Scotland, known with certainty to predate any of the nation’s railway tunnels. The handrail was added far later (obviously, as it would interfere with the reins of a horse), as were the mounted electric lights. As such, this must have been a genuinely challenging navigation hazard for the horse-drawn narrowboats it was built to accommodate!

On the other side the canal passes over mighty aqueducts spanning a series of wooded valleys, and also providing us with yet another geocaching opportunity. We were very selective about our geocache stops on this trip; there were so many candidates but we needed to make progress to ensure that we made it to Edinburgh in good time.

We took lunch and shandy at Bridge 49 where we also bought a painting depicting one of the bridges on the Union Canal and negotiated with the proprietor an arrangement to post it to us (as we certainly didn’t have space for it in our bags!), continuing a family tradition of us buying art from and of places we take holidays to. They let us recharge our batteries (literal this time: we plugged the e-bike in to ensure it’d have enough charge to make it the rest of the way without excessive rationing of power). Eventually, our bodies and bikes refuelled, we pressed on into the afternoon.

For all that we might scoff at the overly-ornate, sometimes gaudy architecture of the Victorian era – like the often-ostentatious monuments of the Necropolis we visited early in our adventure – it’s still awe-inspiring to see their engineering ingenuity. When you stand on a 200-year-old aqueduct that’s still standing, still functional, and still objectively beautiful, it’s easy to draw unflattering comparisons to the things we build today in our short-term-thinking, “throwaway” culture. Even the design of the Falkirk Wheel’s, whose fate is directly linked to these duocentenarian marvels, only called for a 120-year lifespan. How old is your house? How long can your car be kept functioning? Long-term thinking has given way to short-term solutions, and I’m not convinced that it’s for the better.

Eventually, and one further (especially sneaky) geocache later, a total of around 66 “canal miles”, one monsoon, and one sleep from the Glasgow station where we dismounted our bus, we reached the end of the Union Canal in Edinburgh.

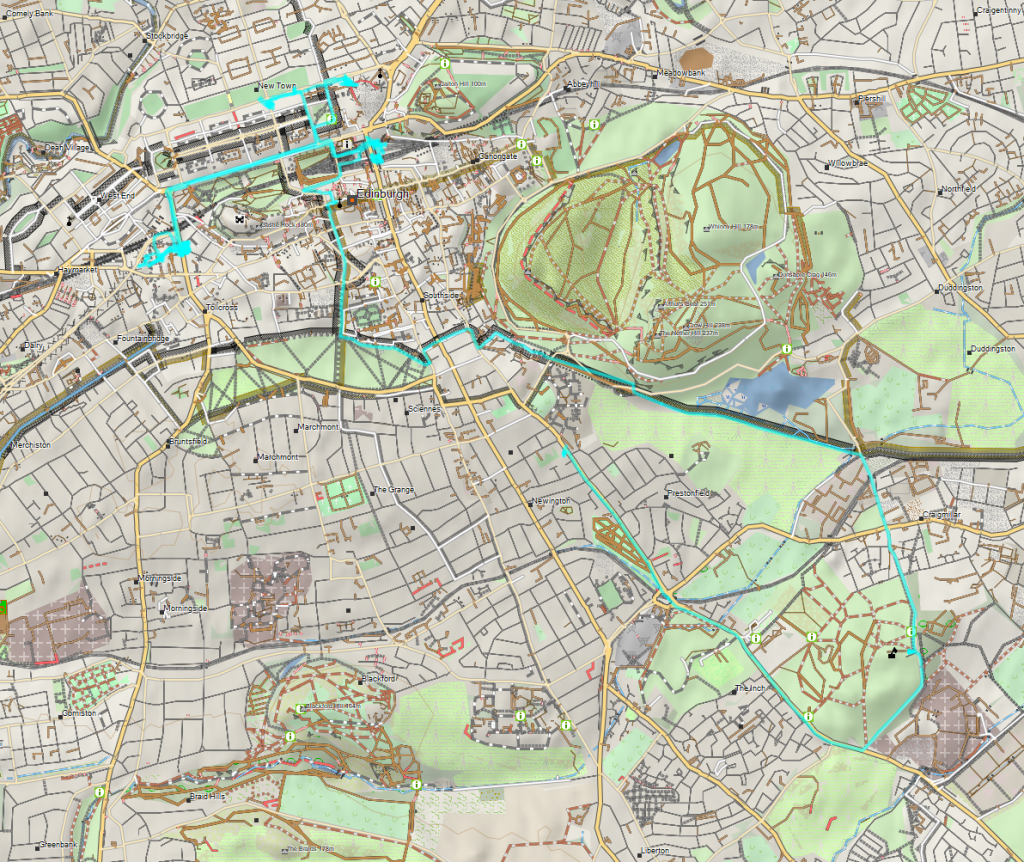

Edinburgh #

There we checked in to the highly-recommendable 94DR guest house where our host Paul and his dog Molly demonstrated their ability to instantly-befriend just-about anybody.

We went out for food and drinks at a local gastropub, and took a brief amble part-way up Arthur’s Seat (but not too far… we had just cycled fifty-something miles), of which our hotel room enjoyed a wonderful view, and went to bed.

The following morning we cycled out to Craigmillar Castle: Edinburgh’s other castle, and a fantastic (and surprisingly-intact) example of late medieval castle-building.

This place is a sprawling warren of chambers and dungeons with a wonderful and complicated history. I feel almost ashamed to not have even known that it existed before now: I’ve been to Edinburgh enough times that I feel like I ought to have visited, and I’m glad that I’ve finally had the chance to discover and explore it.

Edinburgh’s a remarkable city: it feels like it gives way swiftly, but not abruptly, to the surrounding countryside, and – thanks to the hills and forests – once you’re outside of suburbia you could easily forget how close you are to Scotland’s capital.

In addition to a wonderful touch with history and a virtual geocache, Craigmillar Castle also provided with a delightful route back to the city centre. “The Innocent Railway” – an 1830s stretch of the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway which retained a tradition of horse-drawn carriages long after they’d gone out of fashion elsewhere – once connected Craigmillar to Holyrood Park Road along the edge of what is now Bawsinch and Duddington Nature Reserve, and has long since been converted into a cycleway.

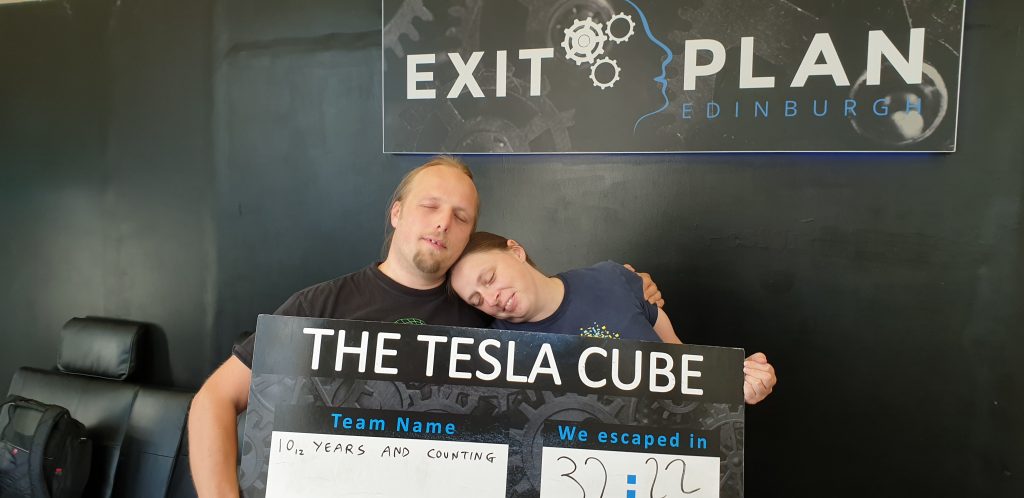

Making the most of our time in the city, we hit up a spa (that Ruth had secretly booked as a surprise for me) in the afternoon followed by an escape room – The Tesla Cube – in the evening. The former involved a relaxing soak, a stress-busting massage, and a chill lounge in a rooftop pool. The latter undid all of the good of this by comprising of us running around frantically barking updates at one another and eventually rocking the week’s highscore for the game. Turns out we make a pretty good pair at escape rooms.

Southwards #

After a light dinner at the excellent vegan cafe Holy Cow (who somehow sell a banana bread that is vegan, gluten-free, and sugar-free: by the time you add no eggs, dairy, flour or sugar, isn’t banana bread just a mashed banana?) and a quick trip to buy some supplies, we rode to Waverley Station to find out if we’d at least be able to get a sleeper train home and hoping for not-another-bus.

We got a train this time, at least, but the journey wasn’t without its (unnecessary) stresses. We were allowed past the check-in gates and to queue to load our bikes into their designated storage space but only after waiting for this to become available (for some reason it wasn’t immediately, even though the door was open and crew were standing there) were we told that our tickets needed to be taken back to the check-in gates (which had now developed a queue of their own) and something done to them before they could be accepted. Then they reprogrammed the train’s digital displays incorrectly, so we boarded coach B but then it turned into coach E once we were inside, leading to confused passengers trying to take one another’s rooms… it later turned back into coach B, which apparently reset the digital locks on everybody’s doors so some passengers who’d already put their luggage into a room now found that they weren’t allowed into that room…

…all of which tied-up the crew and prevented them from dealing with deeper issues like the fact that the room we’d been allocated (a room with twin bunks) wasn’t what we’d paid for (a double room). And so once their seemingly-skeleton crew had solved all of their initial technical problems they still needed to go back and rearrange us and several other customers in a sliding-puzzle-game into one another’s rooms in order to give everybody what they’d actually booked in the first place.

In conclusion: a combination of bad signage, technical troubles, and understaffing made our train journey South only slightly less stressful than our bus journey North had been. I’ve sort-of been put off sleeper trains.

After a reasonable night’s sleep – certainly better than a bus! – we arrived in London, ate some breakfast, took a brief cycle around Regent’s Park, and then found our way to Marylebone to catch a train home.

All in all it was a spectacular and highly-memorable adventure, illustrative of the joy of leaving planning to good-luck, the perseverance of wet cyclists, the ingenuity of Victorian engineers, the beauty of the Scottish lowlands, the cycle-friendliness of Glasgow, and – sadly – the sheer incompetence of the operators of sleeper trains.

A++, would celebrate our love this way again.