This week our usual Dungeons & Dragons group took a week off while our DM recovered from a long and tiring week. As a “filler”, I offered to facilitate a game of Dialect: A Game About Language and How It Dies, from Thorny Games, who I discovered through a Metafilter post about their latest free print-and-play game, Sign: A Game about Being Understood. Yes, all of their games about about language and communication; what of it?

Dialect

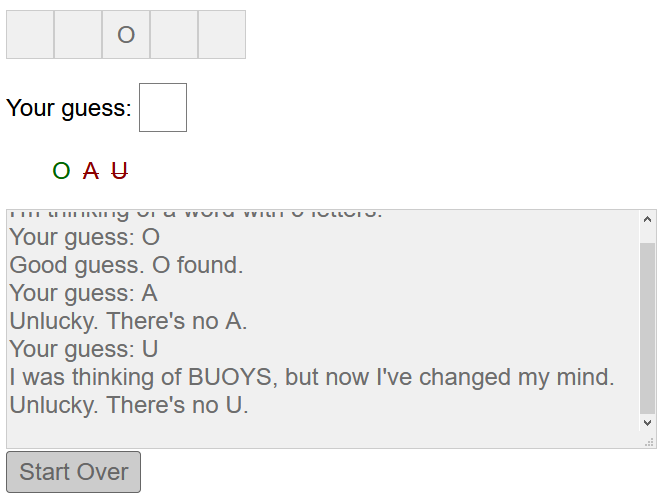

Dialect could be described as a rules-light, GM-less (it has a “facilitator” role, but they have no more authority than any player on anything), narrative-driven/storytelling roleplaying game based on the concept of isolated groups developing their own unique dialect and using the words they develop as a vehicle to tell their stories.

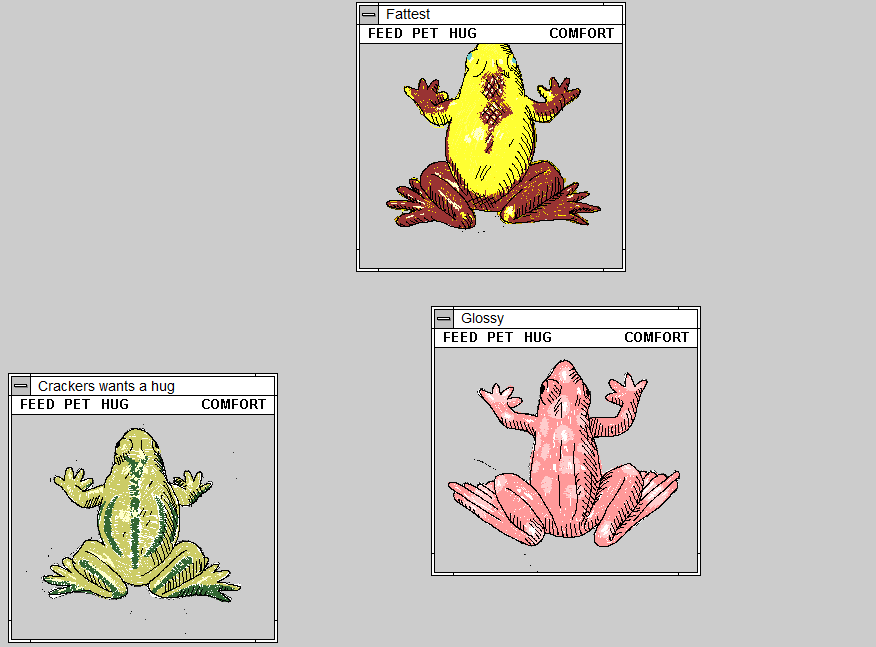

This might not be the kind of RPG that everybody likes to play – if you like your rules more-structured, for example, or you’re not a fan of “one-shot”/”beer and pretzels” gaming – but I was able to grab a subset of our usual roleplayers – Alec, Matt R, Penny, and I – and have a game (with thanks to Google Meet for videoconferencing and Roll20 for the virtual tabletop: I’d have used Foundry but its card support is still pretty terrible!).

The Outpost

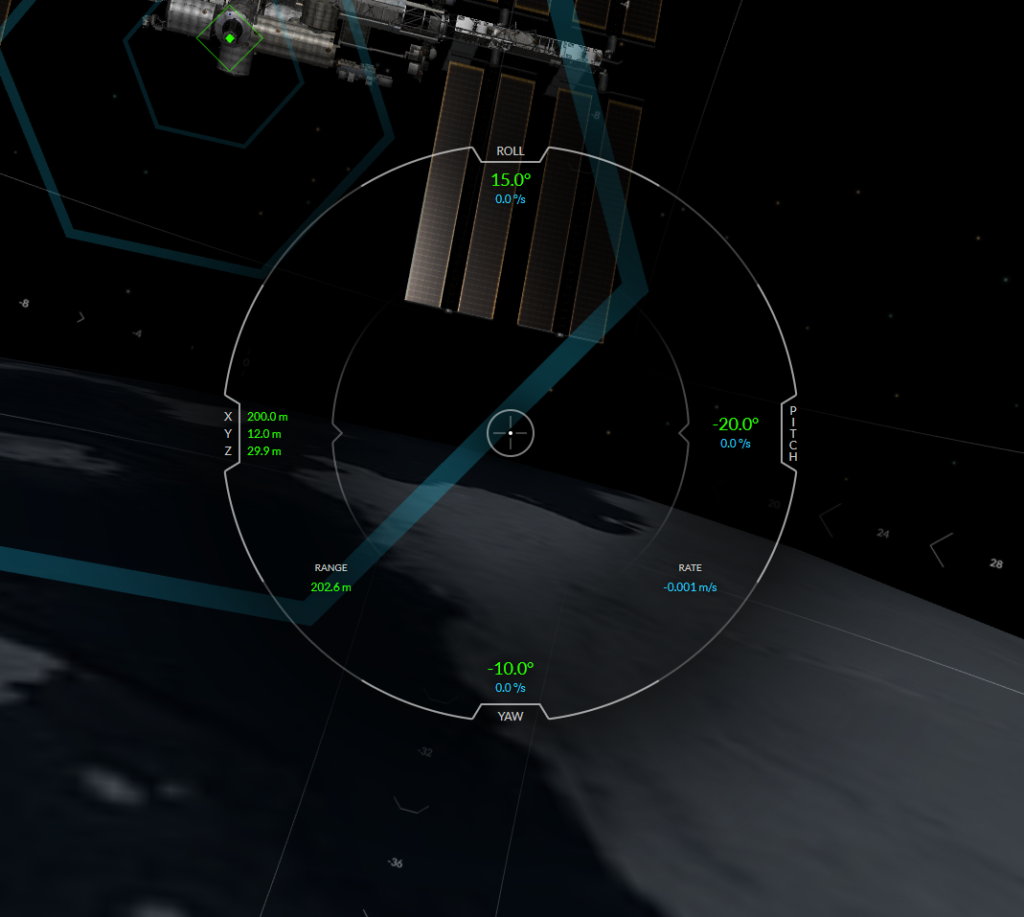

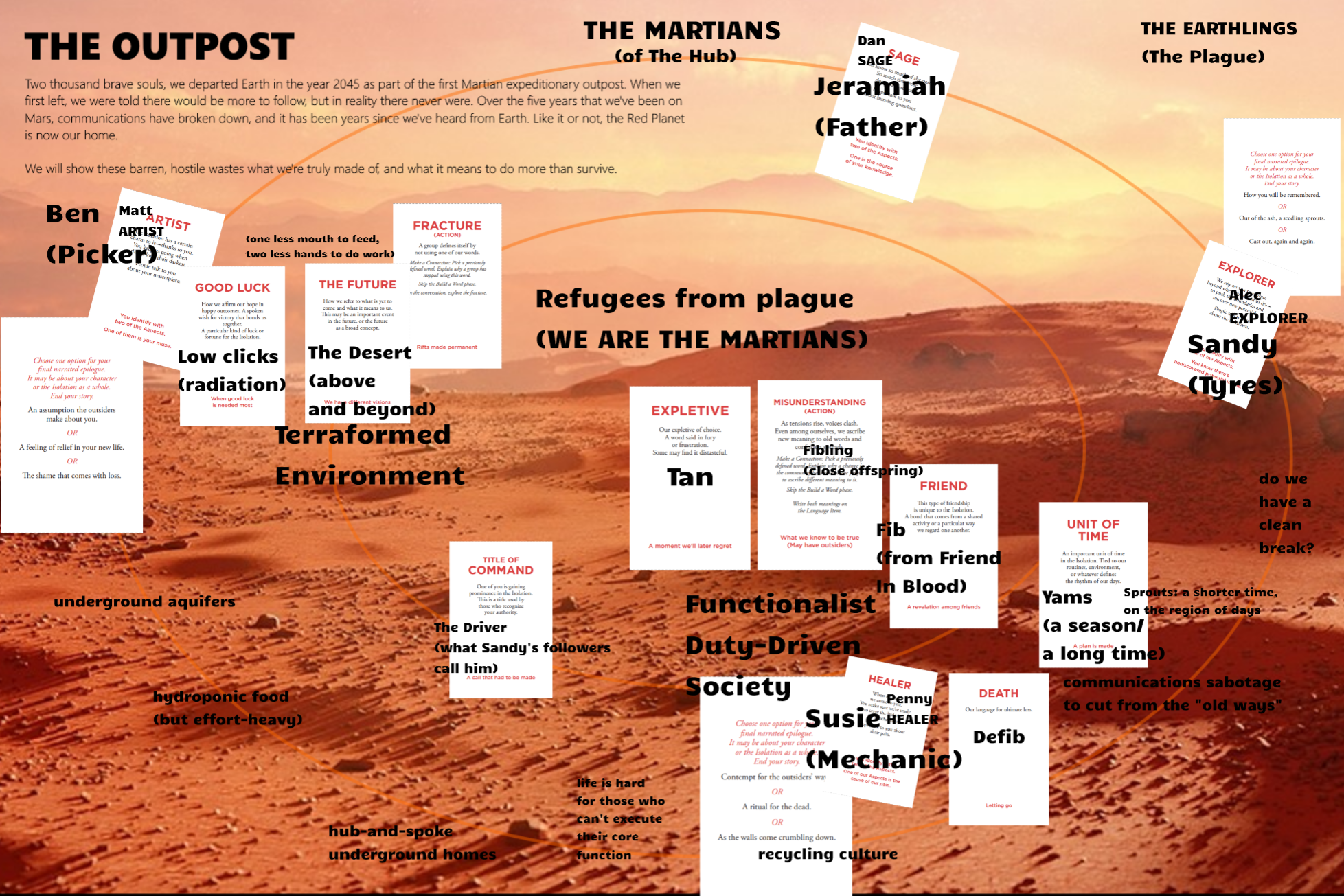

A game of Dialect begins with a backdrop – what other games might call a scenario or adventure – to set the scene. We opted for The Outpost, which put the four of us among the first two thousand humans to colonise Mars, landing in 2045. With help from some prompts provided by the backdrop we expanded our situation in order to declare the “aspects” that would underpin our story, and then expand on these to gain a shared understanding of our world and society:

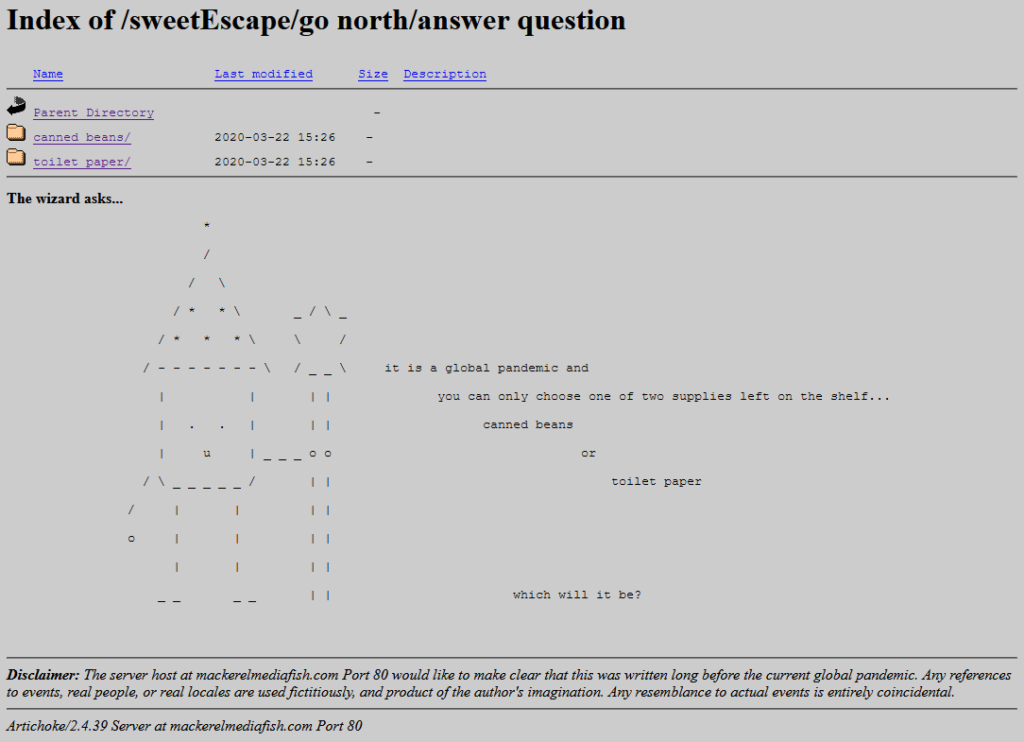

- Refugees from plague: Our expedition left Earth to escape from a series of devastating plagues that were ravaging the planet, to try to get a fresh start on another world.

- Hostile environment: Life on Mars is dominated by the ongoing struggle for sufficient food and water; we get by, but only thanks to ongoing effort and discipline and we lack some industries that we haven’t been able to bootstrap in the five years we’ve been here (we had originally thought that others would follow).

- Functionalist, duty-driven society: The combination of these two factors led us to form a society based on supporting its own needs; somewhat short of a caste system, our culture is one of utilitarianism and unity.

It soon became apparent that communication with Earth had been severed, at least initially, from our end: radicals, seeing the successes of our new social and economic systems, wanted to cement our differences by severing ties with the old world. And so our society lives in a hub-and-spoke cave system beneath the Martian desert, self-sustaining except for the need to send rovers patrolling the surface to scout for and collect valuable surface minerals.

In this world, and prompted by our cards, we each developed a character. I was Jeramiah, the self-appointed “father” of the expedition and of this unusual new social order, who remembers the last disasters and wars of old Earth and has revolutionary plans for a better world here on Mars, based on controlled growth and a planned economy. Alec played Sandy – “Tyres” to their friends – a rover-driving explorer with one eye always on the horizon and fresh stories for the colony brought back from behind every new crater and mountain. Penny played Susie, acting not only as the senior medic to the expedition but something more: sort-of the “mechanic” of our people-driven underground machine, working to keep alive the genetic records we’d brought from Earth and keep them up-to-date as our society eventually grew, in order to prevent the same kinds of catastrophe happening here. “Picker” Ben was our artist, for even a functionalist society needs somebody to record its stories, celebrate its accomplishments, and inspire its people. It’s possible that the existence of his position was Jeramiah’s doing: the two share a respect for the stark, barren, undeveloped beauty of the Martian surface.

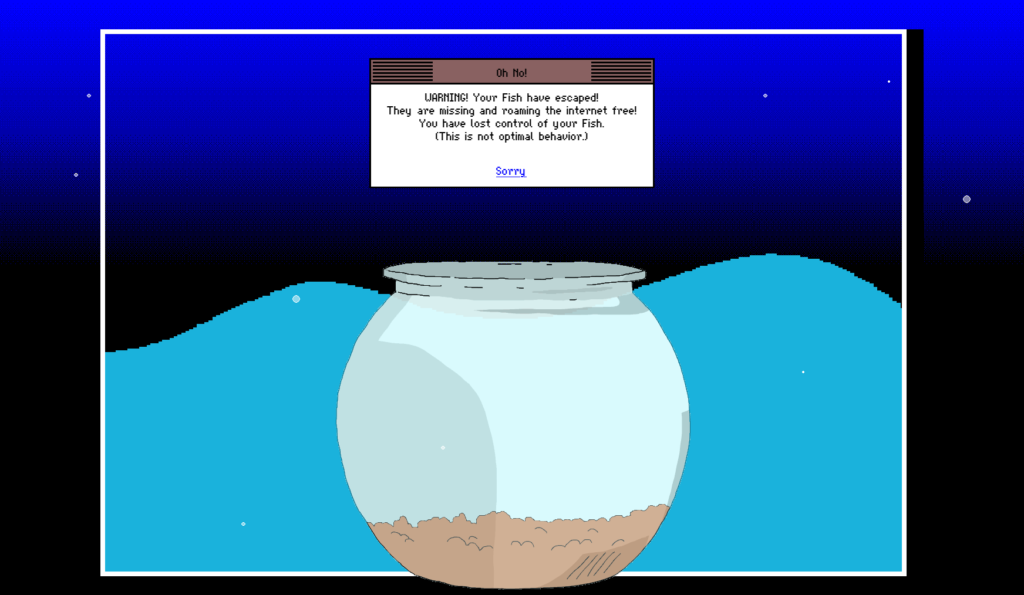

We developed our language using prompt cards, improvised dialogue, and the needs of our society. But the decades that followed brought great change. More probes began to land from Earth, more sophisticated than the ones that had delivered us here. They brought automated terraforming equipment, great machines that began to transform Mars from a barren wasteland into a place for humans to thrive. These changes fractured our society: there were those that saw opportunity in this change – a chance to go above ground and live in the sun, to expand across the planet, to make easier the struggle of our day-to-day lives. But others saw it as a threat: to our way of life, which had been shaped by our challenging environment; to our great social experiment, which could be ruined by the promise of an excessive lifestyle; to our independence, as these probes were clearly the harbingers of the long-promised second wave from Earth.

Even as new colonies were founded, the Martians of the Hub (the true Martians, who’d been here for yams time, lived and defibed here, not these tanning desert-dwellers that followed) resisted the change, but it was always going to be a losing battle. Jeramiah took his last breath in an environment suit atop a dusty Martian mountain a day’s drive from the Hub, watching the last of the nearby deserts that was still untouched by the new green plants that had begun to spread across the surface. He was with his friend Sandy, for despite all of the culture’s efforts to paint them as diametrically opposed leaders with different ideas of the future, they remained friends until the end. As the years went by and more and more colonists arrived, Sandy left for Phobos, always looking for a new horizon to explore. Sick of the growing number of people who couldn’t understand his language or his art, Ben pioneered an expedition to the far side of the planet where he lived alone, running a self-sustaining agri-home and exploring the hills until his dying day. We were never sure where Susie ended up, but it wasn’t Mars: she’d talked about joining humanity’s next big jump, to the moons of Jupiter, so perhaps she’s out there on one of the colonies of Titan or Europa. Maybe, low clicks, she’s even keeping our language alive out there.

Retrospective

The whole event was a lot of fun and I’m keen to repeat it, perhaps with a different group and a different backdrop. The usual folks know who they are, but if you’re not one of those and you want in next time we play, drop me a message of some kind.