TL;DR: Quick access to GIF MD5 hasquine

ressources:

Introduction

A few days ago, Ange Albertini retweteed an tweet from 2013

asking for a document that shows its own MD5 or SHA1 hash.

Later, he named such a document an hashquine, which seems to be appropriate: in computing, a quine is a program that prints its own source code when run.

Now, creating a program that prints its own hash is not that difficult, as several ways can be used to retrieve its source code before computing the hash (the second method does not

work for compiled programs):

- Reading its source or compiled code (e.g. from disk);

- Using the same technique as in a quine to get the source code.

However, conventional documents such as images are likely not to be Turing-complete, so computing their hash is not possible directly. Instead, it is possible to leverage hash

collisions to perform the trick.

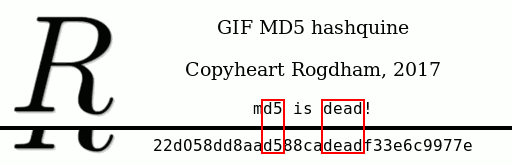

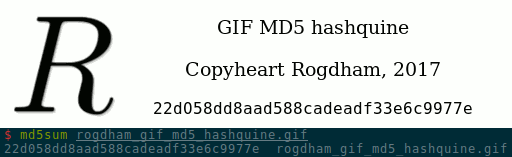

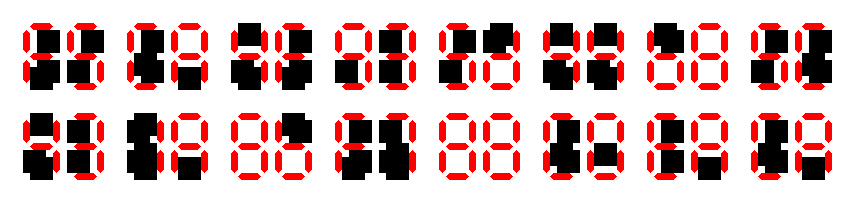

This is the method that I used to create the following GIF

MD5 hashquine:

Once I managed to do create it, I figured out that it was not the first GIF MD5 hashquine ever

made, since spq beat me to it.

I will take that opportunity to look at how that one was done, and highlight the differences.

Finally, my code is on Github, so if you want to create your own gif md5 hashquine, you could easily start from there!

Creating a GIF MD5 hashquine

To create the hasquine, the two following ressources were used exhaustively:

A note about MD5 collisions

We say that MD5 is obsolete because one of the properties of a cryptographic

hash function is that it should not be possible to find two messages with the same hash.

Today, two practical attacks can be performed on MD5:

- Given a prefix

P, find two messages M1 and M2 such as md5(P || M1) and md5(P || M2) are equal (||

denotes concatenation);

- Given two prefixes

P1 and P2, find two messages M1 and M2 such as md5(M1 || P1) and md5(M2 || P2) are

equal.

To the best of my knowledge, attack 1 needs a few seconds on a regular computer, whereas attack 2 needs a greater deal of ressources (especially, time). We will use attack 1 in the following.

Please also note that we are not able (yet), given a MD5 hash H, to find a message M such as md5(M) is

H. So creating a GIF displaying a fixed MD5 hash and then bruteforcing some bytes

to append at the end until the MD5 is the one displayed is not possible.

Overview

The GIF file format does not allow to perform arbitrary computations. So we can not ask the software used to display the image to

compute the MD5. Instead, we will rely on MD5 collisions.

First, we will create an animated GIF. The first frame is not interesting, since it’s only displaying the background. The second frame

will display a 0 at the position of the first character of the hash. The third frame will display a 1 at that same position. And so on and so forth.

In other words, we will have a GIF file that displays all 16 possibles characters for each single character of the MD5 “output”.

If we allow the GIF to loop, it would look like this:

Now, the idea is, for each character, to comment out each frame but the one corresponding to the target hash. Then, if we don’t allow the GIF to loop, it will end displaying the target MD5 hash, which is what we want.

To do so, we will, for each possible character of the MD5 hash, generate a MD5 collision at some place in

the GIF. That’s 16×32=512 collisions to be generated, but we average 3.5 seconds per collision on our computer so it

should run under 30 minutes.

Once this is done, we will have a valid GIF file. We can compute its hash: it will not change from that point.

Now that we have the hash, for each possible character of the MD5 hash, we will chose one or the other collision “block” previously computed. In

one case, the character will be displayed, on the other it will be commented out. Because we replace some part of the GIF file with

the specific collision “block” previously computed at that very same place, the MD5 hash of the GIF file will not change.

All what is left to do is to figure out how to insert the collision “blocks” in the GIF file (they look mostly random), so that:

- It is a valid GIF file;

- Using one “block” displays the corresponding character at the right position, but using the other “block” will not display it.

I will detail the process for one character.

Example for one character

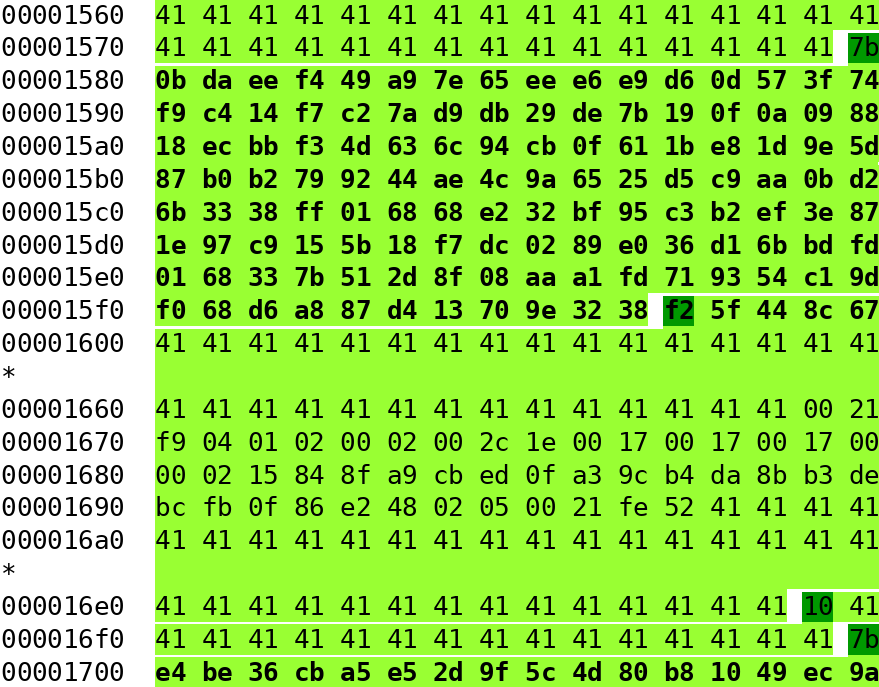

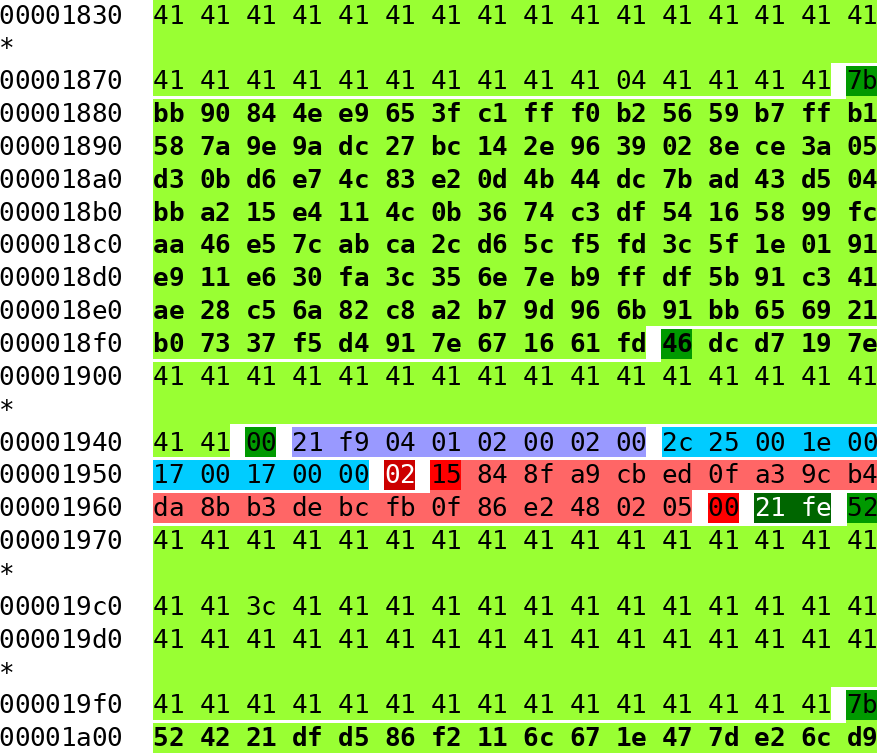

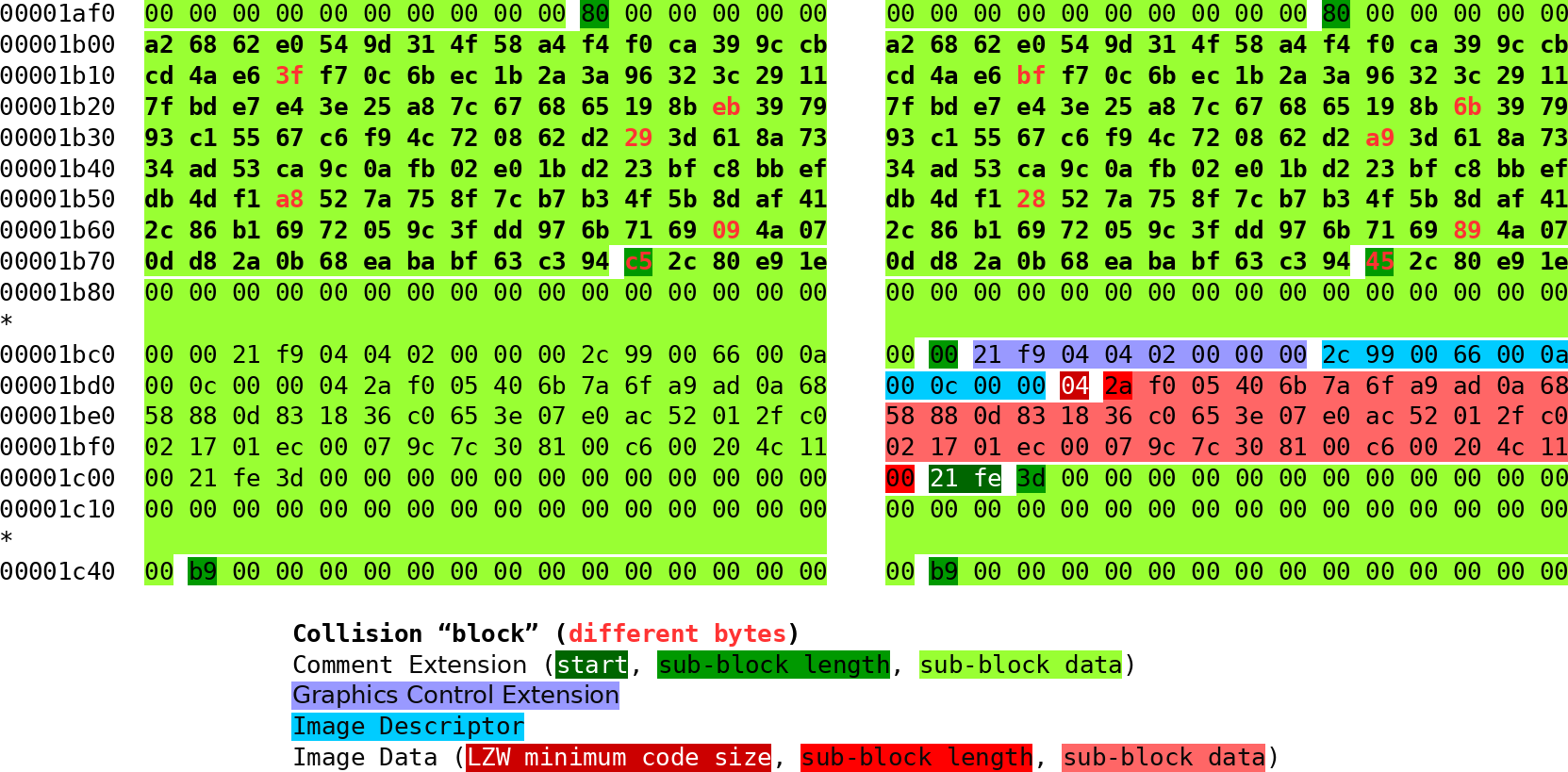

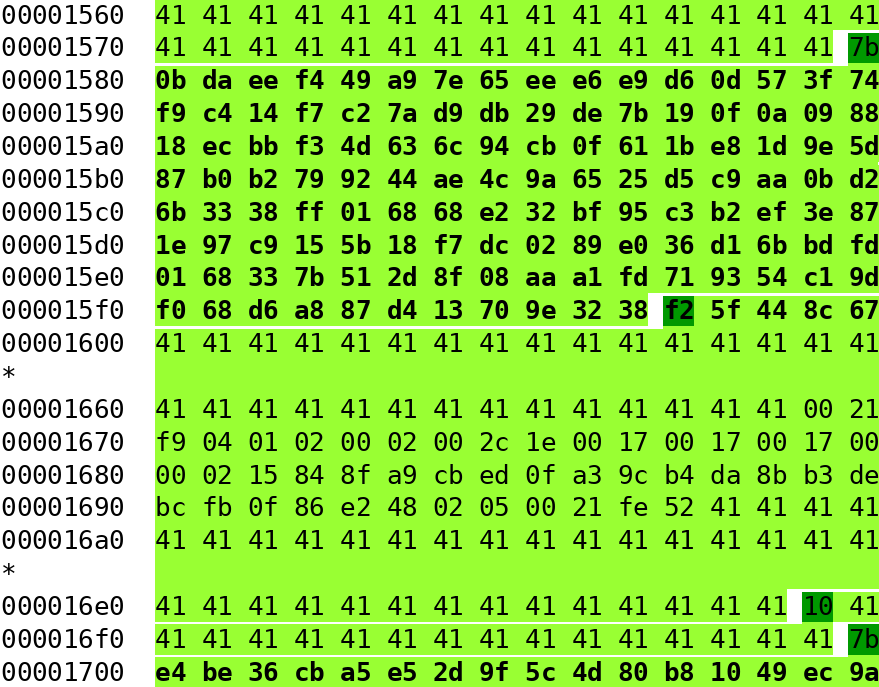

Let’s look at the part of the generated GIF file responsible for displaying (or not) the character 7 at the first

position of the MD5 hash.

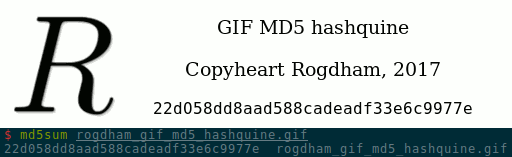

The figure below shows the relevant hexdump displaying side by side the two possible choices for the collision block (click to display in full size):

The collision “block” is displayed in bold (from 0x1b00 to 0x1b80), with the changing bytes written in red.

In the GIF file formats, comments are defined as followed:

- They start with the two bytes

21fe (written in white over dark green background);

- Then, an arbitrary number of sub-blocks are present;

- The first byte (in black over a dark green background) describes the length of the sub-block data;

- Then the sub-block data (in black over a light green background);

- When a sub-block of size

0 is reached, it is the end of the comment.

The other colours in the image above represent other GIF blocks:

- In purple, the graphics control extension, starting a frame and specifying the duration of the frame;

- In light blue, the image descriptor, specifying the size and position of the frame;

- In various shades of red, the image data (just as for comments, it can be composed of sub-blocks).

To create this part of the GIF, I considered the following:

- The collision “block” should start at a multiple of 64 bytes from the beginning of the file, so I use comments to pad accordingly.

- The

fastcoll software generating a MD5 collision seems to always create two outputs where the bytes in position 123 are

different. As a result, I end the comment sub-block just before that position, so that this byte gives the size of the next comment sub-block.

- For one chosen collision “block” (on the left), the byte in position 123 starts a new comment sub-block that skips over the GIF

frame of the character, up to the start of a new comment sub-block which is used as padding to align the next collision “block”.

- For the other chosen collision “block” (on the right), the byte in position 123 creates a new comment sub-block which is shorter in that case. Following it, I end the comment, add

the frame displaying the character of the MD5 hash at the right position, and finally start a new comment up to the comment sub-block used as

padding for the next collision “block”.

All things considered, it is not that difficult, but many things must be considered at the same time so it is not easy to explain. I hope that the image above with the various colours

helps to understand.

Final thoughts

Once all this has been done, we have a proper GIF displaying its own MD5 hash! It is composed of

one frame for the background, plus 32 frames for each character of the MD5 hash.

To speed-up the displaying of the hash, we can add to the process a little bit of bruteforcing so that some characters of the hash will be the one we want.

I fixed 6 characters, which does not add much computations to create the GIF. Feel free to add more if needed.

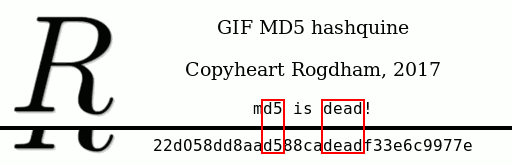

Of course, the initial image (the background) should have those fixed characters in it. I chose the characters d5 and dead as shown in the image below, so

that this speed-up is not obvious!

That makes a total of 28 frames. At 20ms per frame, displaying the hash takes a little over half a second.

Analysis of a GIF MD5 hashquine

Since I found out that an other GIF MD5 hashquine has been created before mine once I finished

creating one, I thought it may be interesting to compare the two independent creations.

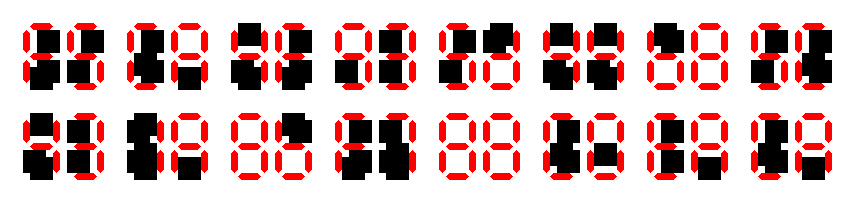

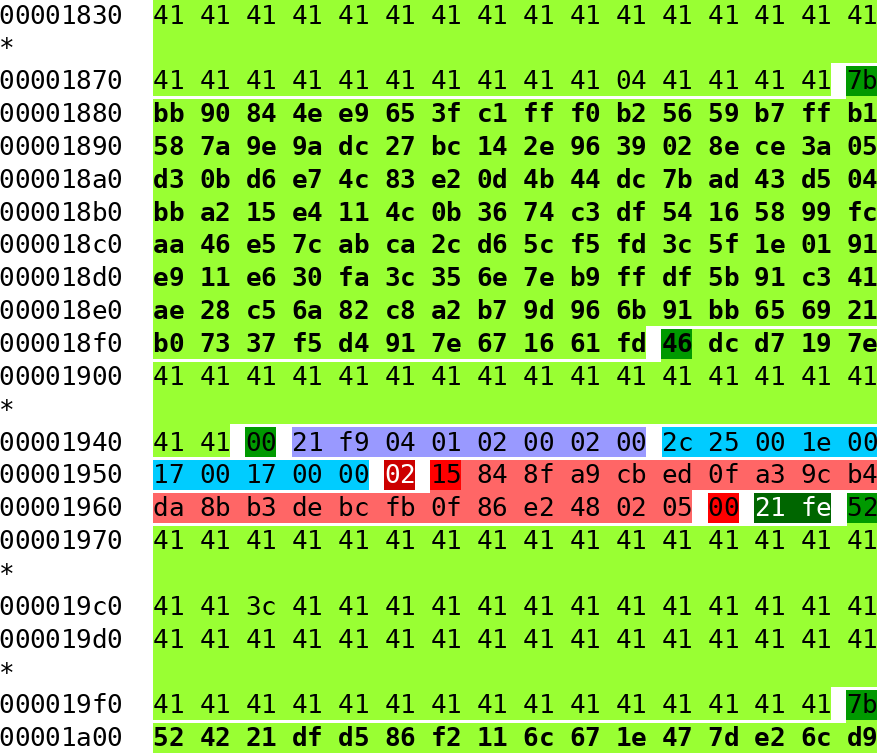

Here is spq’s hashquine:

The first noticeable thing is that 7-digits displays have been used. This is an interesting trade-off:

- On the plus side, this means that only

7×32=224 MD5 collisions are needed (instead of 16×32=512), which should make

the generation of the GIF more than twice as fast, and the image size smaller (84Ko versus 152Ko, but I also chose to feature my

avatar and some text).

- However, there is a total of 68 GIF frames instead of 28, so the GIF takes more

time to load: 1.34 seconds versus 0.54 seconds.

Now, as you can see when loading the GIF file, a hash of 32 8 characters is first displayed, then each segment needed to

be turned off is hidden. This is done by displaying a black square on top. Indeed, if we paint the background white, the final image looks like this:

My guess is that it was easier to do so, because there was no need to handle all 16 possible characters. Instead, only a black square was needed.

Also, the size (in bytes) of the black square (42 bytes) is smaller than my characters (58 to 84 bytes), meaning that it is more likely to fit. Indeed, I needed to consider the case

in my code where I don’t have enough space and need to generate an other collision.

Other than that, the method is almost identical: the only difference I noticed is that spq used two sub-block comments or collision alignment and skipping over the collision bytes,

whereas I used only one.

For reference, here is an example of a black square skipped over:

And here is another black square that is displayed in the GIF:

Conclusion

Hashquines are fun! Many thanks to Ange Albertini for the challenge, you made me dive into the GIF file format, which I probably

wouldn’t have done otherwise.

And of course, well done to spq for creating the first known GIF MD5 hashquine!