I’ve long been a fan of Hugh Howey‘s Wool series of books (especially the first and third;

the second’s a bit weaker); in fact I’ve been enjoying re-reading them as a bedtime story for our eldest!

Naturally, when I heard that it would become a TV series I was really excited! I’m enjoying

the series so far, especially thanks to its epic casting. It diverges a lot from the books –

sometimes in ways I love, sometimes in ways that confuse me – but that’s not what I wanted to talk about. I wanted to share how cool the opening credits sequence is!

Spoiler warning: even if you’re following the TV series there are likely to be major spoilers below based on my recollection of the books!

We open on the sun shining above a thick layer of all-obscuring clouds, tinted sickly yellow like poison gas, then descend into the darkness below. This hints at the uninhabitability of

the world above, foreshadows Lukas stargazing through gaps in the clouds,

and foreshadows revelations about the argon gas used to flush the airlocks. The descent feels representative of humanity’s migration from the sunlit surface to the underground silos.

Looking down, we see the silo from above in a desolate landscape, introducing the world and its setting. The area around it is shrouded and hostile, reflecting the residents’ view of

the outside world as unsurvivable, but also masking our view of the other nearby silos that we might otherwise be able to see.

Descending “into” this representation of the silo, we get a view for only a split second that looks distinctly like the platter and spindle of a magnetic hard disk drive, broken-up as

if to represent corruption. This reflects a number of major plot points in the first season relating to the destruction and recovery of secret information from ancient storage devices.

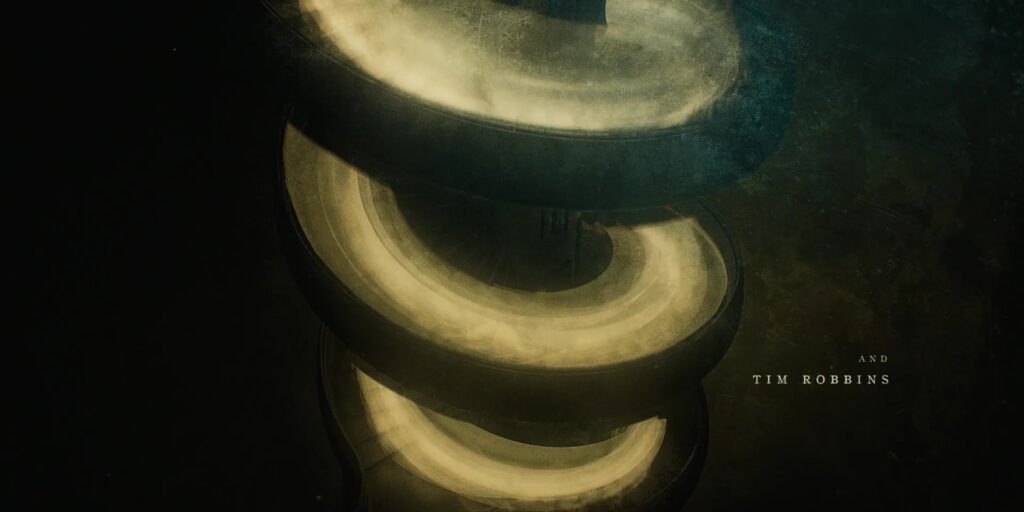

Truly within the silo now, we see the spokes of landings radiating out from the great stairwell. The shape is reminiscient of a cog: a motif we’ll return to later. Humanoid shapes made

of light, like you get in a long exposure, move around, giving both the idea of a surveillance state, and setting us up to think of all such “glowing spots” as people (relevant later in

the credits).

A representation of the stairwell itself appears, with a lit gaseous substance whipping up and down it. Given that we’ve just been shown that this kind of “light” represents people,

it’s easy to see this as showing us the traffic that grinds up and down the silo, but it also feels like looking at part of a great machine, pumping gas through a condenser: notice that

there’s no landings any more: this is all about the never-ending traffic.

A landing appears, and the gaseous forms are now more-clearly humanoid, almost as if they’re ghosts (perhaps pointing to the number of generations who’ve lived before, in this place, or

else a reference to Juliette’s investigation into the lives of those who lived before her).

More swirling gas-people, this time below an empty balconette: perhaps a nod to the source of Juliette’s uncommon name (in the books, it’s taken from Romeo & Juliet, a

possibly-illicit copy of which is retained by the silo and performed prior to Juliette’s birth and for at least a short while afterwards: she writes mechanical notes on the back of a

playscript), or perhaps a reference to George’s death after “falling” from a balcony.

Seen from a different angle, the colour shifts, and the gas/ghosts become white like the argon spray of the airlock. The people are all part of a machine: a machine that sends people

outside to clean and die. But more than that, the blue comes to represent a clean/perfect view of what a silo can be: a blueprint representation of the goals of its creators to

shape the inhabitants into their vision of the future:

We refocus on the shape of the silo itself, but just for a split second the view looks more like an x-ray… of a human spine? As if to remind us that it’s people who upload the

system of the silo, just as its concrtete uploads its physical structure. Also a reminder that the silo is treated (by those who manage it, both within and beyond it) as an

organic thing that can be nurtured, grown, or if necessary killed.

This becomes the structure of the silo, but it almost looks architectural: a “clean” look, devoid of people or signs of life, like a blueprint, perhaps foreshadowing Donald’s role in

designing the structures that will eventually become the silos. The “space” between the arms is emphasised, showing how the social system that this structure imposes serves to separate

and segregate people: classism is a recurring theme in both the books and the TV series, and it eventually becomes apparent that the silos are specifically organised to reduce

communication between interdependent groups.

Returning to the “populated” silo – swirls of gas spiralling away down (or up: it’s no longer clear!), we catch a glimpse of a nautilus shell at the centre. The nautilus is a “living

fossil”, a creature from a bygone era that continues to survive in our modern world, which is an excellent metaphor for the population of the dead world who go on living beneath its

surface. The nautilus shell is a recurring image within the TV series: Gloria’s visions of the world that came before see her clutching one and tracing its shape, for example.

We cut to what appears to be a seed, representing both the eventual conclusion of the story (Juliette, Charlotte and the Silo 18 survivors’ discovery of the cache of supplies that will

allow them to begin rebuilding the world) and also the nature of the silo. The seed we see initially

appears to fail and degrade, becoming nothing at all, before eventually growing into the beginnings of a strong new plant. This could represent the eventual and inevitable collapse of

silo 18, among others, but the eventual flourishing of those that survive, or on a broader scale the collapse of modern civilization to be replaced by the silos, or even of the silo

system to be replaced with that which follows it after the conclusion of the story. Lots of options!

It’s also possibly a reflection of the harsh and opaque eugenics/population control mechanism imposed by the “lottery”, which becomes a major plot point in the TV series much earlier

than in the books.

We cut to trees, thriving despite a yellow fog. The sky can’t be seen, which is a reminder that all of humanity’s resources must now be produced underground (trees are especially rare

and prized, leading to a shortage of paper.

It seems to be deliberately left unclear whether the trees we see are on the surface before the fall of humanity, on the surface after the fall, or grown underground.

A fruit falls from the tree, which links back to the seed we saw geminate earlier but also seems likely to be a representation of the concept of original sin. The grand idea of the

silos was to create a better world on the other side of a man-made catastrophe, but this idea is inherently flawed because the systems that are constructed by the same people who are

complicit in the destruction of the world that came before. The structure that’s put in place through the Pact carries the weight of the sins of its creators: even though the

inhabitants of silo 1 ultimately intend to destroy themselves, they’re unable to create a new world that is both better than the one that came before and free from their

influence: it’s an impossibility.

It’s also possibly a representation of the religious beliefs of some inhabitants that the creators of the silo should be revered as gods. This was a recurring plot point in the books

but has been somewhat muted in the TV series so far.

The metaphor continues when we see that this falling fruit is already beginning to rot, degrading as it tumbles towards the earth. We don’t see it strike the ground: it almost seems to

hover in the air, uncertain and undecided, and reflective of the eventual end when the inhabitants of the silos break free from the shackles of the system that’s been constructed for

them and can choose their own destiny. Or perhaps we don’t see the collision simply because the camera continues to fall down into the earth and below the surface again?

This time, wer’e very deep: all the way down in the depths of Mechanical, at the bottom of the silo: home to our heroine and source of many aspects of the story. In the centre, a shaft

descends, connecting us back to the “spine” of the silo – the great staircase – but it’s harder to see as a wealth of machinery appears to support it, occluding our view. From down here

in Mechanical it appears that the machines keep the silo running, whereas further up it looked like humans pumped through it like blood, which reflects Juliette’s disagreements with

many of those up-top about their priorities during her time as Sheriff and, later, as Mayor.

We see a cloud of steam, like that used to drive the generator that brings life to the silo, and for a moment it’s impossible to differentiate it from the cloud of people we saw

earlier, rushing up and down the stairs. Look closely at the steam, though, and you’ll see that it too contains the ghosts of people.

Deeper still, the cog motif returns and we’re buried in an impossible number of interconnected gears. The machine that they support is impossible to comprehend from within: How big is

it? What is it for? Who made it and why?

The final cog mutates into the staircase again, winding away from us and hammering the point home.

The staircase changes again, first becoming an outline of itself (a callback to the “blueprint” design we saw earlier, reminding us that this thing was designed to be like

this)…

…but this becomes a double-helix, representing the chaos of life. Again, the metaphor is of a perfect idea constructed to achieve a goal, but the unpredictability of humans

leads to a different outcome.

Seen from above, the staircase now looks like an enormous clock, a machine of cogs each turning slower than the one beneath, counting down until the end of the silo experiment in

accordance with the whim of its creators. Except, of course, if something were to break this machine.

Seen from the side, the silo is a hive of activity, but the shape the levels form in this depiction are exactly like the rotors of a steam turbine, and this is reflected by an image of

steam, almost in the shape of a growing tree – passing behind it in the background. The generator and its rotor blades is a significant early plot point in both the books and the TV

series, and the books in particular use engine metaphors to explain Juliette’s interpretation of different situations she finds herself in, even those which are distinctly interpersonal

rather than mechanical.

Looking back up the silo, towards the light, we can now see its shape and structure for what it is: just another cog – a part of an even bigger machine that is the whole Operation Fifty

silo network. The people are the lifeblood of this machine, but they’re as replaceable and interchangable as any other part.

Finally, we crossfade to the title, looking like a stencil. Each letter is more-degraded than the one before it, representing the impossibility of building a perfect system.

The credits sequence is less than 90 seconds long, but so much is packed into it. It’s just great.

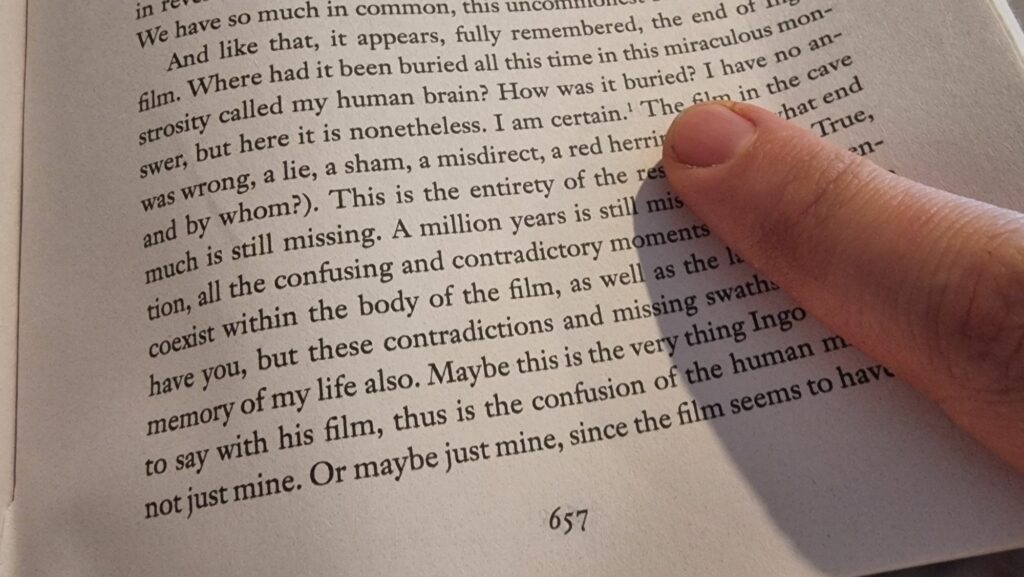

I just finished reading Kate Manne‘s Entitled. I can’t remember where I first heard about it or why I opted

to buy a copy, but it had been sitting in my to-read pile for a while and so I picked it up last month to read over the festive period.

I just finished reading Kate Manne‘s Entitled. I can’t remember where I first heard about it or why I opted

to buy a copy, but it had been sitting in my to-read pile for a while and so I picked it up last month to read over the festive period.