When I was younger, I thought that magic was all about secrets. I’ve since changed my mind. Twice.

That the secret of magic is secrets isn’t an unreasonable assumption. We all know that magicians famously don’t reveal how their tricks work, so it feels like the secrecy is what makes magic… magical. When as a kid I watched Paul Daniels make an elephant disappear on his (oh-so 1980s) TV show, and I remember being struck by the fact that he must be privy to some kind of guarded knowledge, and my school friends and I would speculate wildly as to what it was. I saw the same kind of speculation when Derren Brown predicted the lottery a few years back: although the age of the Internet changed the nature of the discussion, making them more global and perhaps more-cynical (not helped, perhaps, by Derren’s “explanation”).

But as time went on, I came to learn that the key to magic isn’t secrets.

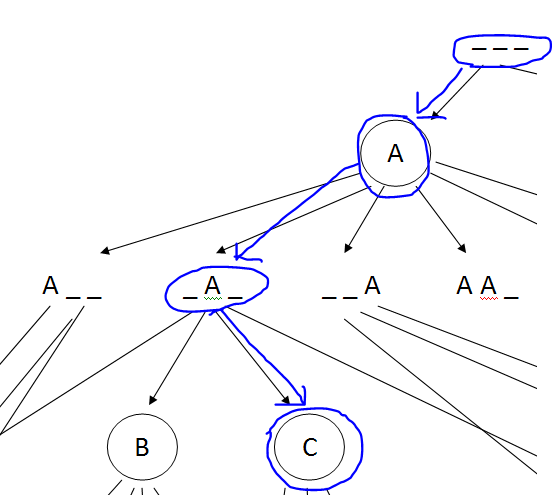

That’s not to say that secrets aren’t important to the enjoyment of magic – they truly are. In the case of 95%+ of all of the magic tricks you’ve ever seen, you’d be considerably less-impressed if you knew how they were done! And that’s because, most of the time, the principle behind any illusion is something so simple that you just can’t see it for looking. As my childhood interest in magic grew, I acquired a small collection of props and books (one of which I rediscovered while removing things from my late father’s house, the other year), and my model changed: in an age when information is as easily-available as your local library, magic isn’t about secrets, I decided, but about practice.

Practice, practice, practice. A magician’s art starts alone, possibly in front of a mirror. And then it stays there for… quite a long time. If they’re interested in doing anything beyond the most-basic card tricks, a card magician has at least half a dozen different moves and sleights to perfect, from which they’ll be able to derive a multitude of different effects.

(There’s an anecdote about a young magician who tells her mentor that she’s learned a hundred tricks, and asks how many he knows. He thinks for a moment, and then he replies, “I would say about nine.” If you feel like you ‘got’ the joke in that story, then you’re probably either a magician or else a Buddhist: there are some strange similarities between the two.)

If they want to learn how to link rings or rejoin cut ropes or make things levitate, then the same rules apply. But even while that’s true, and practice is absolutely critical… practice is also not the secret of magic.

The key to magic – the thing that’s even more important than secrets and practice is… showmanship. I’ll come back to that, but first, let me tell you how I lost and, later, rediscovered magic.

I loved magic as a kid, but my interest in it (as a performer, at least) sort-of dwindled in my early-to-mid teens. I can’t explain why; but you’d be forgiven for assuming that perhaps I was distracted by discovering, like many teenage boys do, a different kind of ‘one-handed shuffle’ that provided far more-instant satisfaction. In any case: aside from a few basically-self-working card tricks here and there, I didn’t perform any magic at all for almost twenty years.

Until Christmas of 2013.

At Christmas, Ruth‘s little brother Robin visited. And at some point – and I’m not even sure why – he said, “I want to learn a card trick. Does anybody know any card tricks?”

“I might know a couple,” I said, thinking back and trying to put my mind to one, as I reached for a pack of cards, “Here: give these a shuffle…” I can’t remember what I performed first: probably a classic like Out Of This World or the Chicago Opener: something lightweight, and easy to learn, and based entirely in muscle-memory manoeuvres and not in anything as complex as even a basic misdirection.

And somehow that act of teaching Robin a couple of beginner card tricks, and challenging him to take that knowledge and develop them some more… that simple act was enough to flip a switch in my brain. Suddenly, I wanted to jump headlong back into magic again.

Since last time around, there’s not only books (and so many great books) but also DVDs from which to learn (and relearn) magical principles. I’ve been learning new sleights as fast as my brain – and my hands – can take it, and gradually building a repertoire of effects that fall somewhere between confusing and delighting. Because I’ve for so-long had such a strong belief in the importance of practice, I’ve been trying to find excuses to perform: to such an extent that I’ll spend some of my lunchtimes in any given week hanging around in Oxford’s public spaces, performing for random passers-by. Practice in front of a mirror is good and everything, but practice in front of a stranger is so much-more valuable… especially when you’re forced to think on your feet after a spectator does something that you didn’t anticipate!

I also accidentally ended up starting a local magic club: I joined a thread of people bemoaning the lack of a club in Oxford, on a forum on which I participate, and after I’d found a couple of other guys who felt them same way, suggested a date, time, and venue, and made it happen. Now it happens every month, and we few are the closest thing Oxford’s got to a magic society.

But yes: showmanship. If there’s a secret to magic, then it’s that. Any fool can find your card in the deck (even if you don’t know a way to do this – the “secret” – then I can guarantee that at least one of your friends does). Any magician can do it in several different ways (the “practice”), and thus keep you guessing by eliminating the options – how did he do it blindfolded? But a magic trick is only as enjoyable to watch as it is well-presented: like any entertainer, and perhaps more than many, a magician relies on their presentation style to make the difference…

This is an opinion that sometimes puts me at odds with some of the other magicians in the club. I’ll demonstrate a new routine I’m working on, and they’ll ask how it was done… and when I reveal that I used the cheapest, simplest, easiest or plainly cheekiest approach possible, they’ll be instantly less-impressed. There are plenty of magicians more-talented than I, for whom the artistry comes from the practice, and to see somebody achieve what is – to a layperson – the same result in a way that requires less sleight-of-hand or a less-subtle misdirection than ‘their’ way is apparently a little grating! They’d rather perform an illusion using their best moves and their most-sophisticated sleights than to simply do it “well enough” to get the desired effect (and thus, the desired reaction). Certainly, it’s desirable to have several ways to perform the same trick (just in case you end up performing it twice), but those ways don’t all have to be the most-complicated approaches you know: sometimes the magical equivalent of “look behind you, a three-headed monkey” is more than enough.

(For those with access to the Mega Man Lounge, I’ve kicked off a debate about this very topic.)

This video later inspired a video, which you can watch here.