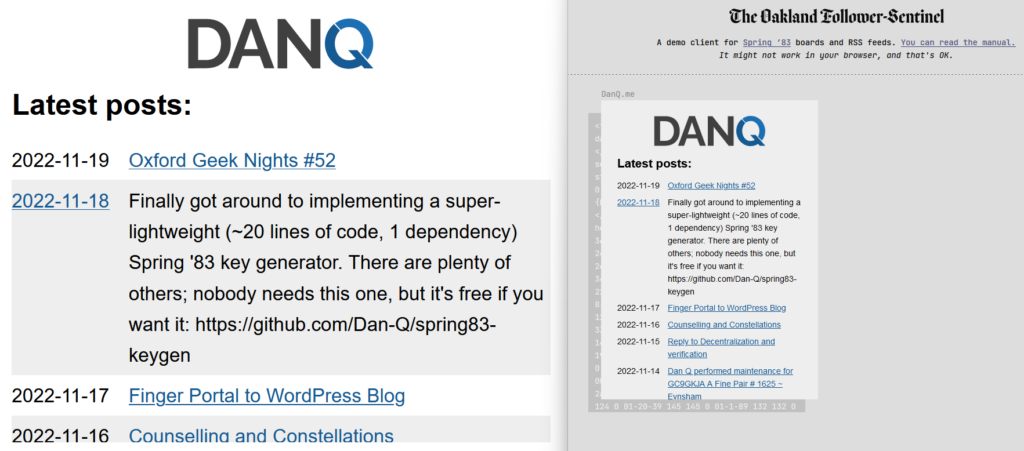

Just in time for Robin Sloan to give up on Spring ’83, earlier this month I finally got aroud to launching STS-6 (named for the first mission of the Space Shuttle Challenger in Spring 1983), my experimental Spring ’83 server. It’s been a busy year; I had other things to do. But you might have guessed that something like this had been under my belt when I open-sourced a keygenerator for the protocol the other day.

If you’ve not played with Spring ’83, this post isn’t going to make much sense to you. Sorry.

Introducing STS-6

My server is, as far as I can tell, very different from any others in a few key ways:

- It does not allow third-party publishing at all. Some might argue that this undermines the aim of the exercise, but I disagree. My IndieWeb inclinations lead me to favour “self-hosted” content, shared from its owners’ domain. Also: the specification clearly states that a server must implement a denylist… I guess my denylist simply includes all keys that are not specifically permitted.

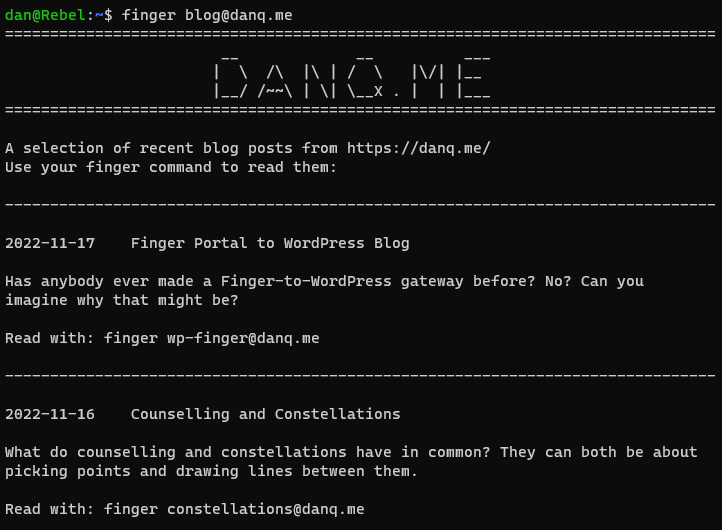

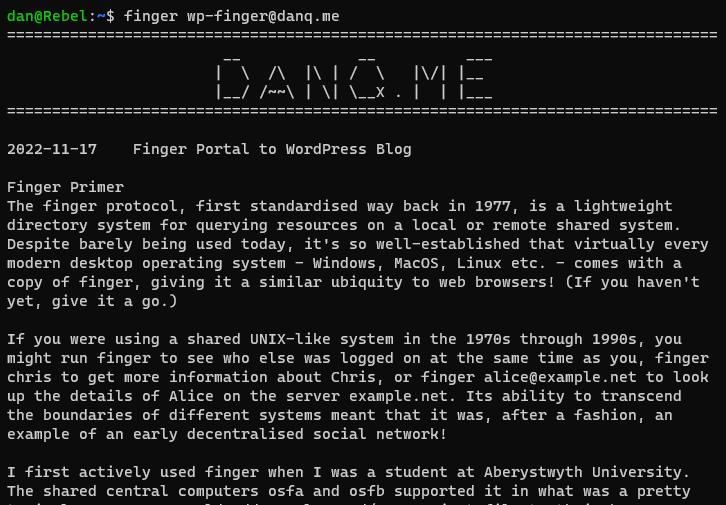

- It’s geared towards dynamic content. My primary board self-publishes whenever I produce a new blog post, listing the most recent blog posts published. I have another half-implemented which shows a summary of the most-recent post, and another which would would simply use a WordPress page as its basis – yes, this was content management, but published over Spring ’83.

-

It provides helpers to streamline content production. It supports internal references to other boards you control using the format

{{board:123}}which are automatically converted to addresses referencing the public key of the “current” keypair for that board. This separates the concept of a board and its content template from that board’s keypairs, making it easier to link to a board. To put it another way, STS-6 links are self-healing on the server-side (for local boards). - It helps automate content-fitting. Spring ’83 strictly requires a maximum board size of 2,217 bytes. STS-6 can be configured to fit a flexible amount of dynamic content within a template area while respecting that limit. For my posts list board, the number of posts shown is moderated by the size of the resulting board: STS-6 adds more and more links to the board until it’s too big, and then removes one!

-

It provides “hands-off” key management features. You can pregenerate a list of keys with different validity periods and the server will automatically cycle through

them as necessary, implementing and retroactively-modifying

<link rel="next">connections to keep them current.

I’m sure that there are those who would see this as automating something that was beautiful because it was handcrafted; I don’t know whether or not I agree, but had Spring ’83 taken off in a bigger way, it would always only have been a matter of time before somebody tried my approach.

From a design perspective, I enjoyed optimising an SVG image of my header so it could meaningfully fit into the board. It’s pretty, and it’s tolerably lightweight.

If you want to see my server in action, patch this into your favourite Spring ’83 client:

https://s83.danq.dev/10c3ff2e8336307b0ac7673b34737b242b80e8aa63ce4ccba182469ea83e0623

A dead end?

Without Robin’s active participation, I feel that Spring ’83 is probably coming to a dead end. It’s been a lot of fun to play with and I’d love to see what ideas the experience of it goes on to inspire next, but in its current form it’s one of those things that’s an interesting toy, but not something that’ll make serious waves.

In his last lab essay Robin already identified many of the key issues with the system (too complicated, no interpersonal-mentions, the challenge of keys-as-identifiers, etc.) and while they’re all solvable without breaking the underlying mechanisms (mentions might be handled by Webmention, perhaps, etc.), I understand the urge to take what was learned from this experiment and use it to help inform the decisions of the next one. Just as John Postel’s Quote of the Day protocol doesn’t see much use any more (although maybe if my finger server could support QotD?) but went on to inspire the direction of many subsequent “call-and-response” protocols, including HTTP, it’s okay if Spring ’83 disappears into obscurity, so long as we can learn what it did well and build upon that.

Meanwhile: if you’re looking for a hot new “like the web but lighter” protocol, you should probably check out Gemini. (Incidentally, you can find me at gemini://danq.me, but that’s something I’ll write about another day…)