Today, I can overhear the two guys who are digging a trench through my garden.

Guy 1: Does this look like a gas pipe to you?

Guy 2: Dunno. But we can’t dig round it soo…

😬

Today, I can overhear the two guys who are digging a trench through my garden.

Guy 1: Does this look like a gas pipe to you?

Guy 2: Dunno. But we can’t dig round it soo…

😬

Way back in the day, websites sometimes had banners or buttons (often 88×31 pixels, for complicated historical reasons) to indicate what screen resolution would be the optimal way to view the site. Just occasionally, you still see these today.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Folks who were ahead of the curve on what we’d now call “responsive design” would sometimes proudly show off that you could use any resolution, in the same way as they’d proudly state that you could use any browser1!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I saw a “best viewed at any size” 88×31 button recently, and it got me thinking: could we have a dynamic button that always shows the user’s current resolution as the “best” resolution. So it’s like a “best viewed at any size” button… except even more because it says “whatever resolution you’re at… that’s perfect; nice one!”

Turns out, yes2:

![]()

Anyway, I’ve made a website: best-resolution.danq.dev. If you want a “Looks best at [whatever my visitor’s screen resolution is]” button, you can get one there.

It’s a good job I’ve already done so many stupid things on the Web, or this would make me look silly.

1 I was usually in the camp that felt that you ought to be able to access my site with any browser, at any resolution and colour depth, and get an acceptable and satisfactory experience. I guess I still am.

2 If you’re reading this via RSS or have JavaScript disabled then you’ll probably see an “any size” button, but if you view it on the original page with JavaScript enabled then you should see your current browser inner width and height shown on the button.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This post advocates minimizing dependencies in web pages that you do not directly control. It conflates dependencies during build time and dependencies in the browser. I maintain that they are essentially the same thing, that both have the same potential problems, and that the solution is the snappy new acronym HtDTY – Host the Damn Thing Yourself.

…

If your resources are large enough to cause a problem if you Host the Damn Things Yourself then consider finding ways to cut back on their size. Or follow my related advice – HtDToaSYHaBRW IMCYMbT(P)WDWYD : Host the Damn Thing on a Service You Have A Business Relationship With, It May Cost You Money But They (Probably) Won’t Dick With Your Data.

…

Host the Damn Thing Yourself (HtDTY) is an excellent suggestion; I’ve been a huge fan of the philosophy for ages, but I like this acronym. (I wish it was pronounceable, but you can’t have everything.)

Andrew’s absolutely right, but I’m not even sure he’s expressed all the ways in which he’s right. Here are my reasons to HtDTY, especially for frontend resources:

So yeah: HtDTY. I dig it.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Scroll art is a form of ASCII art where a program generates text output in a command line terminal. After the terminal window fills, it begins to scroll the text upwards and create an animated effect. These programs are simple, beautiful, and accessible as programming projects for beginners. The SAM is a online collection of several scroll art examples.

Here are some select pieces:

- Zig-zag, a simple periodic pattern in a dozen lines of code.

- Orbital Travels, sine waves intertwining.

- Toggler, a woven triangular pattern restricted to two characters.

- Proton Stream, a rapid, chaotic lightning pattern.

There are two limitations to most scroll art:

- Program output is limited to text (though this could include emoji and color.)

- Once printed, text cannot be erased. It can only scroll up.

But these restrictions compel creativity. The benefit of scroll art is that beginner programmers can create scroll art apps with a minimal amount of experience. Scroll art requires knowing only the programming concepts of print, looping, and random numbers. Every programming langauge has these features, so scroll art can be created in any programming language without additional steps. You don’t have to learn heavy abstract coding concepts or configure elaborate software libraries.

…

Okay, so: scroll art is ASCII art, except the magic comes from the fact that it’s very long and as your screen scrolls to show it, an animation effect becomes apparent. Does that make sense?

Here, let me hack up a basic example in… well, QBASIC, why not:

Anyway, The Scroll Art Museum has lots of them, and they’re much better than mine. I especially love the faux-parallax effect in Skulls and Hearts, created by a “background” repeating pattern being scrolled by a number of lines slightly off from its repeat frequency while a foreground pattern with a different repeat frequency flies by. Give it a look!

vole.wtf’s 1% guild wasn’t the easiest club to gain membership of, but somehow keeping my phone alive for long enough to snap this screenshot was even harder.

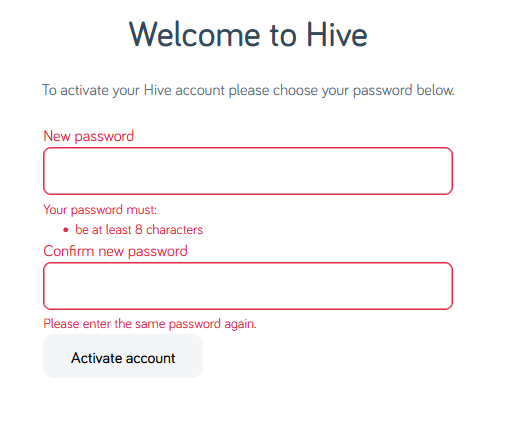

Hey, let’s set up an account with Hive. After the security scares they faced in the mid-2010s, I’m sure they’ll be competent at making a password form, right?

Your password must be at least 8 characters; okay.

Your password must be at least 8 characters; okay.

Just 8 characters would be a little short in this day and age, I reckon, but what do I care: I’m going to make a long and random one with my password safe anyway. Here we go:

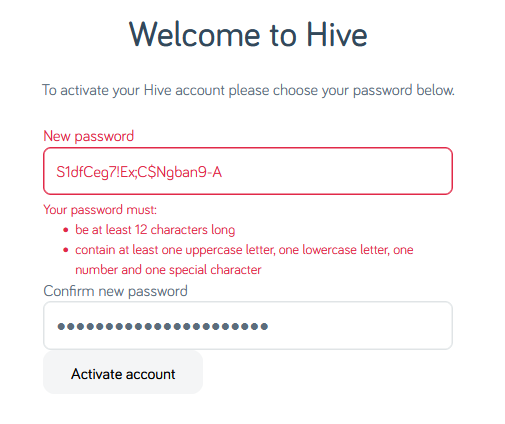

I’ve unmasked the password field so I can show you what I tried. Obviously the password I eventually chose is unrelated to any of my screenshots.

I’ve unmasked the password field so I can show you what I tried. Obviously the password I eventually chose is unrelated to any of my screenshots.

Now my password must be at least 12 characters long, not 8 as previously indicated. That’s still not a problem.

Oh, and must contain at least one of four different character classes: uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and special characters. But wait… my proposed password already does contain all of those things!

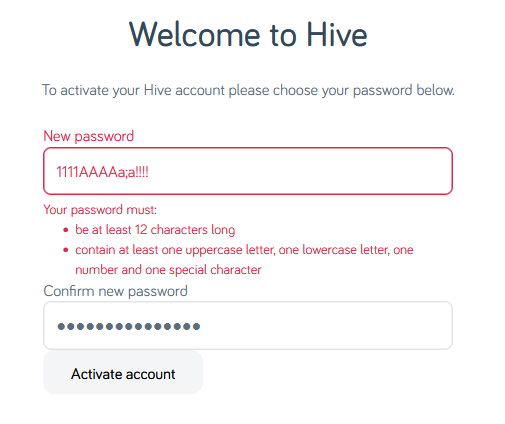

The password 1111AAAAaaaa!!!! is valid… but S1dfCeg7!Ex;C$Ngban9-A is not. I guess my password is too

strong?

Composition rules are bullshit already. I’d already checked to make sure my surname didn’t appear in the password in case that was the problem (on a few occasions services have forbidden me from using the letter “Q” in random passwords because they think that would make them easier to guess… wot?). So there must be something else amiss. Something that the error message is misleading about…

A normal person might just have used the shit password that Hive accepted, but I decided to dig deeper.

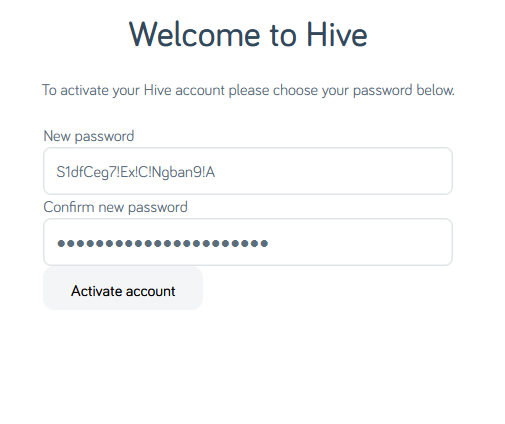

Using the previously-accepted password again but with a semicolon in it… fails. So clearly the problem is that some special characters are forbidden. But we’re

not being told which ones, or that that’s the problem. Which is exceptionally sucky user experience, Hive.

Using the previously-accepted password again but with a semicolon in it… fails. So clearly the problem is that some special characters are forbidden. But we’re

not being told which ones, or that that’s the problem. Which is exceptionally sucky user experience, Hive.

At this point it’s worth stressing that there’s absolutely no valid reason to limit what characters are used in a password. Sometimes well-meaning but ill-informed

developers will ban characters like <, >, ' and " out of a misplaced notion that this is a good way to protect against XSS and

injection attacks (it isn’t; I’ve written about this before…), but banning ; seems especially obtuse (and inadequately explaining that in

an error message is just painfully sloppy). These passwords are going to be hashed anyway (right… right!?) so there’s really no reason to block any character, but anyway…

I wondered what special characters are forbidden, and ran a quick experiment. It turns out… it’s a lot:

- , . + = " £

^ # ' ( ) { } * | < >

: ` – also space

! @ $ % & ?

What the fuck, Hive. If you require that users add a “special” character to their password but there are only six special characters you’ll accept (and they don’t even include the most common punctuation characters), then perhaps you should list them when asking people to choose a password!

Or, better yet, stop enforcing arbitrary and pointless restrictions on passwords. It’s not 1999 any more.

I eventually found a password that would be

accepted. Again, it’s not the one shown above, but it’s more than a little annoying that this approach – taking the diversity of punctuation added by my password safe’s generator and

swapping them all for exclamation marks – would have been enough to get past Hive’s misleading error message.

I eventually found a password that would be

accepted. Again, it’s not the one shown above, but it’s more than a little annoying that this approach – taking the diversity of punctuation added by my password safe’s generator and

swapping them all for exclamation marks – would have been enough to get past Hive’s misleading error message.

Having eventually found a password that worked and submitted it…

…it turns out I’d taken too long to do so, so I got treated to a different misleading error message. Clearly the problem was that the CSRF token had expired, but instead they told me that the activation URL was invalid.

If I, a software engineer with a quarter of a century of experience and who understands what’s going wrong, struggle with setting a password on your site… I can’t begin to image the kinds of tech support calls that you must be fielding.

Do better, Hive.

Somebody just called me and quickly decided it was a wrong number. The signal was bad and I wasn’t sure I’d heard them right, so I followed up by replying by text.

It turns out they asked Siri to call Three (the mobile network). Siri then presumably searched online, found Three Rings, managed to connect that to my mobile number, and called me.

If Siri’s decided that I represent Three, this could work out even worse than that time Google shared my phone number.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Dogspinner is the Monday morning distraction you didn’t know you needed. Get that dog up to full speed! (It’s worth it for the sound effects alone.)

I had some difficulty using it on desktop because I use the Forbidden Resolutions. But it probably works fine for most people and is probably especially great on mobile.

I’d love to write a longer review to praise the art style and the concept, but there’s not much to say. Just… go and give it a shot; it’ll improve your day, I’m sure.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

I think of ElonStan420 standing in that exhibit hall, eyeing those cars with disdain because all that time, energy, care, and expression “doesn’t really matter”. Those hand-painted pinstripes don’t make the car faster or cheaper. Chrome-plated everything doesn’t make it more efficient. No one is going to look under the hood anyway.

…

Don’t read the comments on HackerNews, Adam! (I say this, but I’ve yet to learn not to do so myself, when occasionally my writing escapes from my site and finds its way over there.)

But anyway, this is a fantastic piece about functionalism. Does it matter whether your website has redundant classes defined in the HTML? It renders the same anyway, and odds are good that nobody will ever notice! I’m with Adam: yes, of course it can matter. It doesn’t have to, but coding is both a science and an art, and art matters.

…

Should every website be the subject of maximal craft? No, of course not. But in a industry rife with KPI-obsessed, cookie-cutter, vibe-coded, careless slop, we could use more lowriders.

Well said, Adam.

I’d never put much thought into it before but a slow cooker is basically the opposite of an air frier.

They’re both relatively small (compared to an oven) hot boxes for cooking food. But an air frier uses the small space to contain as much energy as possible in thir vicinity of the food, while the slow cooker aims to maintain as low a temperature as possible until the food finally cooks itself out of boredom.

Anyway, this is going to be pulled pork in like 8-10 hours. 😋

There’s a question being floated around my corner of the blogosphere, but I think my experience of the answer differs from other bloggers:

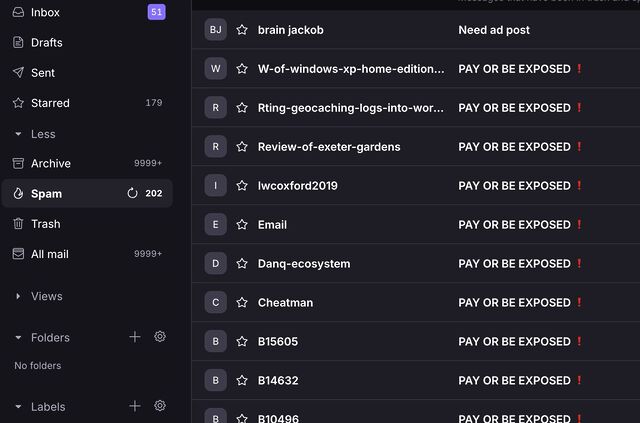

It started when David Bushell observed that, despite having his email address unobscured on his website, he gets more spam via his contact form. Luke Harris followed-up, providing a potential explanation which basically boils down to the idea that it’s both more cost-effective and provides better return-on-investment to spam contact forms than email addresses. And then Kev Quirk described his experience of switching from contact forms to “bare” email addresses and the protections he put in place (like plus-addressing), only to discover that he didn’t need it at all.

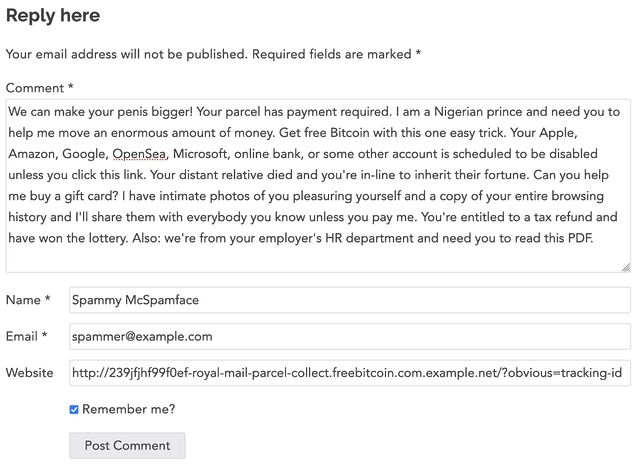

It makes me sad to see the gradual disappearance of the contact form from personal websites. They generally feel more convenient than email addresses, although this is perhaps part of the reason that they come under attack from spammers in the first place! But also, they provide the potential for a new and different medium: the comments area (and its outdated-but-beautiful cousin the guestbook).

Comments are, of course, an even more-obvious target for spammers because they can result in immediate feedback and additional readers for your message. Plus – if they’re allowed to contain hyperlinks – a way of leeching some of the reputability off a legitimate site and redirecting it to the spammers’, in the eyes of search engines. Boo!

But I’ve got to admit: there have been many times that I’ve read an interesting article and not interacted with it simply because the bar to interaction (what… I have to open my email client!?) was too high. I’d prefer to write a response on my blog and hope that webmention/pingback/trackback do their thing, but will they? I don’t know in advance, unless the other party says so openly or I take a dive into their source code to check.

I’ve had both contact/comment forms and exposed email addresses on my website for many years… and I feel like I get aproximately the same amount of spam on both, after filtering. The vast majority of it gets “caught”. Here’s what works for me:

My contact/comments forms use one of a variety of unobtrustive “honeypot”-style traps. These “reverse CAPTCHAs” attempt to trick bots into interacting with them in some particular way while not inconveniencing humans.

I also publish email addresses all over the place, but they’re content-specific. Like Kev, I anticipated spam and so use unique email addresses on different pieces of content: if you want to reply-by-email to this post, for example, you’re encouraged to use the address b27404@danq.me. But this approach has actually provided secondary benefits that are more-valuable:

This strategy works for me: I get virtually no comment/contact form spam (though I do occasionally get a false positive and a human gets blocked as-if they were a robot), and very little email spam (after my regular email filters have done their job, although again I sometimes get false positives, often where humans choose their subject lines poorly).

It might sound like my approach is complicated, but it’s really not. Adding a contact form honeypot is not significantly more-difficult than exposing automatically-rotating email aliases, and for me it’s worth it: I love the convenience and ease-of-use of a good contact/comments form, and want to make that available to my visitors too!

(I also allow one-click reactions with emoji: did you see? Scroll down and send me a bumblebee! Nobody seems to have found a way to spam me with these, yet: it’s not a very expressive medium, I guess!)

Whenever I’m writing a rhyme,

I can’t do the third and fourth line.

Dah-de-da-dah-duh,

Dah-de-de-dah-duh.

But somehow it still works out fine.

Or: Sometimes You Don’t Need a Computer, Just a Brain

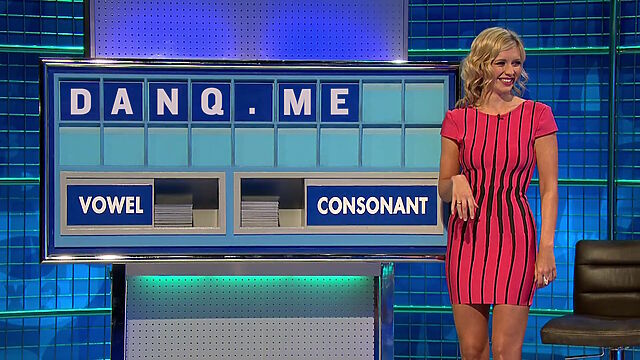

I was watching an episode of 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown the other night1 and I was wondering: what’s the hardest hand you can be dealt in a Countdown letters game?

Sometimes it’s possible to get fixated on a particular way of solving a problem, without having yet fully thought-through it. That’s what happened to me, because the first thing I did was start to write a computer program to solve this question. The program, I figured, would permute through all of the legitimate permutations of letters that could be drawn in a game of Countdown, and determine how many words and of what length could be derived from them2. It’d repeat in this fashion, at any given point retaining the worst possible hands (both in terms of number of words and best possible score).

When the program completed (or, if I got bored of waiting, when I stopped it) it’d be showing the worst-found deals both in terms of lowest-scoring-best-word and fewest-possible-words. Easy.

Here’s how far I got with that program before I changed techniques. Maybe you’ll see why:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby WORDLIST = File.readlines('dictionary.txt').map(&:strip) # https://github.com/jes/cntdn/blob/master/dictionary LETTER_FREQUENCIES = { # http://www.thecountdownpage.com/letters.htm vowels: { A: 15, E: 21, I: 13, O: 13, U: 5, }, consonants: { B: 2, C: 3, D: 6, F: 2, G: 3, H: 2, J: 1, K: 1, L: 5, M: 4, N: 8, P: 4, Q: 1, R: 9, S: 9, T: 9, V: 1, W: 1, X: 1, Y: 1, Z: 1, } } ALLOWED_HANDS = [ # https://wiki.apterous.org/Letters_game { vowels: 3, consonants: 6 }, { vowels: 4, consonants: 5 }, { vowels: 5, consonants: 4 }, ]

At this point in writing out some constants I’d need to define the rules, my brain was already racing ahead to find optimisations.

For example: given that you must choose at least four cards from the consonants deck, you’re allowed no more than five vowels… but no individual vowel appears in the vowel deck fewer than five times, so my program actually had free-choice of the vowels.

Knowing that3, I figured that there must exist Countdown deals that contain no valid words, and that finding one of those would be easier than writing a program to permute through all viable options. My head’s full of useful heuristics about English words, after all, which leads to rules like:

I enjoyed getting “Q” into my proposed letter set. I like to image a competitor, having already drawn two “U”s, a “J”, and a Y”, being briefly happy to draw a “Q” and already thinking about all those “QU-” words that they’re excited to be able to use… before discovering that there aren’t any of them and, indeed, aren’t actually any words at all.

Even up to the last letter they were probably hoping for some consonant that could make it work. A K (juku), maybe?

But the moral of the story is: you don’t always have to use a computer. Sometimes all you need is a brain and a few minutes while you eat your breakfast on a slow Sunday morning, and that’s plenty sufficient.

Update: As soon as I published this, I spotted my mistake. A “yuzu” is a kind of East Asian plum, but it didn’t show up in this countdown solver! So my impossible deal isn’t quite so impossible after all. Perhaps U J Y U Q V U U C would be a better “impossible” set of tiles, where that “C” makes it briefly look like there might be a word in there, even if it’s just a three or four-letter one… but there isn’t. Or is there…?

1 It boggles my mind to realise that show’s managed 28 seasons, now. Sure, I know that Countdown has managed something approaching 9,000 episodes by now, but Cats Does Countdown was always supposed to be a silly one-off, not a show in it’s own right. Anyway: it’s somehow better than both 8 Out Of 10 Cats and Countdown, and if you disagree then we can take this outside.

2 Herein lay my first challenge, because it turns out that the letter frequencies and even the rules of Countdown have changed on several occasions, and short of starting a conversation on what might be the world’s nerdiest surviving phpBB installation I couldn’t necessarily determine a completely up-to-date ruleset.

3 And having, y’know, a modest knowledge of the English language

I’m looking at a listing for a ¼” to ⅝” screw adapter, for which the seller warns that I should “please allow 1-3cm error”.

A 3cm error would mean that a ⅝” screw could result in a screw thread anywhere between 1⅘” and… minus half an inch, I guess? (I don’t even know how to make the concept of negative lengths fit into my brain.)

I suppose this seller could send me an empty envelope and declare that it contained an infinitesimally small adapter. At which point… I’d be the one that was screwed!